Night Flyer: Harriet Tubman and the Faith Dreams of a Free People by Tiya Miles; Penguin Press, 336 pp., $30

Araminta Ross, or “Minty,” was born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in the 1820s. Catastrophe marked her early life. She was six years old when she was sent away from her mother to work as a weaver; three of her sisters were sold into the Deep South. As a teenager, Minty suffered a blow to the head, delivered by an overseer, that left her prone to chronic pain, nightmares, visions, and epileptic seizures. In her early 20s, she adopted her mother’s given name and her husband’s surname—and that is how history remembers her, as Harriet Tubman. “Names were important to enslaved people,” Tiya Miles writes in Night Flyer. Tubman was hardly the first formerly enslaved person to reinvent herself. But most people did so after escaping bondage; Tubman began using her new name when she was still in captivity—an early strike against her so-called masters, Miles speculates, that “casts a glow of foreshadowing over her story.”

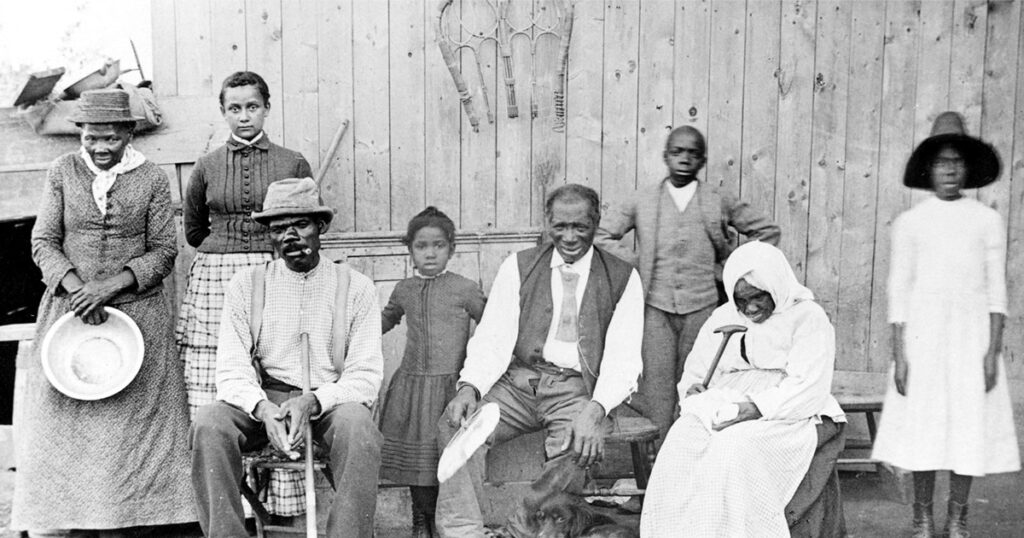

That story is well known. In 1849, Tubman fled her captors and headed north. Under cover of darkness, she walked nearly 150 miles through dense woods and along the banks of creeks and rivers until she reached the safety of Philadelphia. Within a couple of years, at great risk, she began trekking back into slave country to rescue relatives, associates, even strangers. Tubman, five feet tall and slight of build, made 19 such trips in the years prior to the Civil War—at a time when the Fugitive Slave Law meant she or any of her charges could have been apprehended. In the face of this, Tubman began leading road-weary freedom seekers farther north, into southern Ontario, beyond the bounds of American law.

Night Flyer joins nearly a dozen biographies of Tubman, but it doesn’t march in a linear way through the same familiar chronology. Miles’s book is a world-building enterprise, with a novel’s sensitivity and a poet’s sensibility rooted both in Tubman’s daily life and in her more mystical inclinations. Our understanding of Tubman has long been shrouded in myth. “At no time in the history of the Republic has such womanhood ever attained a higher level of excellence than the indomitable heroism of a runaway slave named Harriet Tubman,” wrote literary and social critic Albert Murray in 1970. But how should we account for the mistakes she made? Or the heartbreak she suffered? During her rescues, Tubman pushed herself beyond the point of exhaustion. She likewise disciplined those in her charge with threats of violence or death. On one of her first trips south, she’d gone to bring back her husband, only to discover that he had taken a new wife. When he refused to go with her to Philadelphia, she found others who would, expanding her reach beyond immediate family and friends.

What did Tubman desire for herself? Miles, a professor of history at Harvard, seeks to discover “who she was on the inside.” Primary sources offering insight into Tubman’s early life are few. (Sometimes this was by Tubman’s own design: historians still aren’t certain of the precise route of her initial escape.) Much of what we know has come to us from well-meaning white women, antislavery advocates who nonetheless held a paternalistic view of Black women and their traditions. Miles, by focusing her research on ecology and spirituality, offers us a more complex portrait. She positions Tubman as an intellectual who employed an ecowomanist liberation theology, embodied in her rescues as well as in her speeches, songs, work as a healer, and activism. According to Melanie L. Harris, a professor at Wake Forest University, ecowomanism is a methodology in which “ecowisdom,” defined by “spirit, nature, and humanity,” is practiced by women of African descent. Tubman, in this view, was more than a brave spirit acting on instinct; she was a practitioner of a cogent set of ethics Miles calls “Tubman’s Way,” which had clear origins and lasted until the end of her life.

Tubman came of age during the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening. She “oriented to the world from a place of immersive religious belief,” Miles writes. This was due, at least in part, to her upbringing: she attended a Methodist Episcopal church alongside other Black Marylanders who infused West African traditional practices and beliefs into their Christianity. She prayed often, maintaining a constant stream of communication with the divine that involved songs and incantations, many of which were preserved in interviews. She believed that God spoke to her in the form of dreams and visions. Before her first escape, Tubman endured a series of emotional and spiritual trials, common occurrences in the accounts of many mystics. “Whenever she closed her eyes,” Miles writes, “Harriet saw white men on horseback hunting her people, hunting her.” She dreamed of open fields, border crossings, of flying like a bird. An active belief in the supernatural was not uncommon among “holy” Black women of her era, such as Zilpha Elaw, Old Elizabeth, and Julia A. J. Foote. For them, as for Tubman, their personal relationships with the divine provided the courage necessary to challenge their own subjugation. Tubman saw slavery as an evil that she would fight with God at her side. Miles believes Tubman’s acts of rescue were her form of ministry.

The 19th-century Black women who wrote and preached against slavery believed that the natural world could be a conduit to an encounter with God. Tubman, “arguably the most famous Black woman ecologist in U.S. history,” writes Miles, spoke to trees, memorized the directions of streams, foraged for food, and knew the healing salves that could be extracted from particular plants. She took refuge in the natural world and, during the Civil War, provided intelligence for a Union Army raid on Confederate plantations and supply depots along South Carolina’s Combahee River.

Miles acknowledges that many questions about Tubman’s life remain unanswered. Who taught her so much about the land? What was her meeting with John Brown like? What were the circumstances of her grandmother Modesty’s capture by slave hunters? Still, Miles broadens our understanding of Tubman by treating her as part of a collective of like-minded Black women whose piety and belief in the supernatural she shared—and which emboldened her to set out on a righteous but dangerous path.