The Ripper Revealed

Don’t believe the latest story on the identity of the infamous Victorian

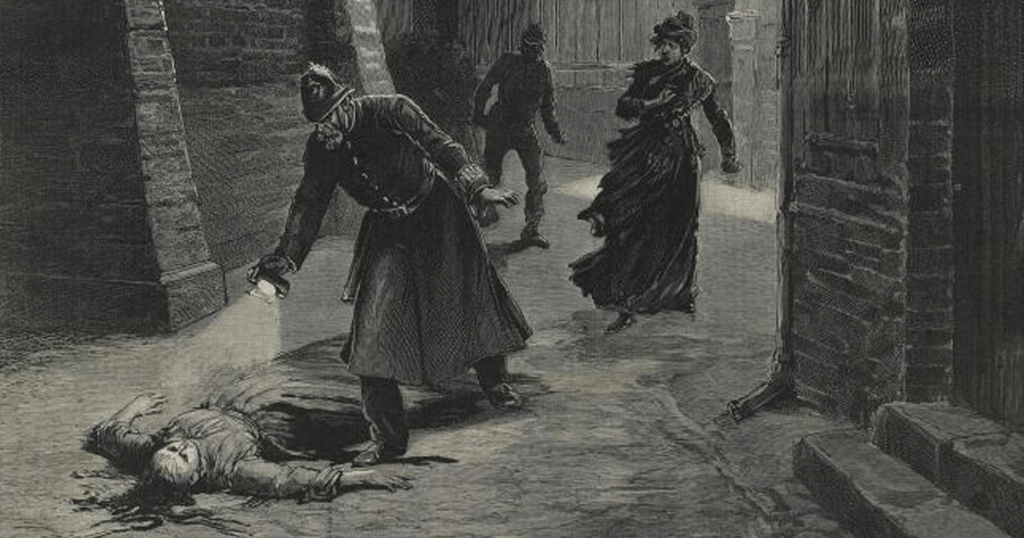

The supposed identity of Jack the Ripper was revealed, again, last week. But we shouldn’t be so quick to close the case. The 131-year-old murder mystery is as fixed in our cultural imagination as the fog-enshrouded Victorian streets of London. The Ripper legend has yielded a seemingly endless list of potential suspects over the years, including author Lewis Carroll and painter Walter Sickert. Now these dubious tales are begetting legends of their own, aided and abetted by dubious science.

Consider the myth that has grown up around a shawl that supposedly belonged to the Ripper’s fourth victim, Catherine Eddowes. Since the shawl’s first appearance in the news in 2014, media outlets have identified Jack the Ripper as Aaron Kosminski, a Polish immigrant who worked in Whitechapel, and whose DNA is said to have been found on Eddowes’s shawl.

But such evidence is far less conclusive than it first appears. Dr. Turi King, a geneticist at the University of Leicester who sequenced the DNA of Richard III, is one of a number of experts who are unconvinced. She told the website Live Science that so many people have handled the shawl over the years that the DNA found on it means very little. Whereas evidence from contemporary crime scenes is collected by technicians wearing protective clothing, face masks, and latex gloves, and is then stored in sealed receptacles, the so-called Eddowes shawl has been handled and exposed to the DNA of untold numbers of people, including the descendants of both Kosminski and Eddowes. “All you need to do is breathe anywhere near the shawl” to put DNA on it, King said. This is especially problematic since the researchers only examined certain low-resolution segments of the mitochondrial DNA, and not nearly enough to rule out many other potential sources. “The fact that there’s a match with a relative, who may or may not have breathed on the shawl in the first place … statistically, that’s not very strong evidence,” King said.

In 2014, when geneticist Adam Rutherford interviewed Jari Louhelainen, the molecular biologist who tested the shawl, Louhelainen himself admitted that the results were not “conclusive” enough to prove the identity of the murderer. According to Rutherford, they were not even up to the standard used in criminal trials today and were an example of “terrible science.”

The incomplete historical record doesn’t help. Researchers who have investigated the Ripper murders are limited by the sparseness of surviving documentation. Much of what is known about the crimes has been taken from the only sources that exist—sensationalised 19th-century newspaper accounts. Catherine Eddowes’s case is an exception. Not only do the original coroner’s inquest documents remain, but also an inventory of the personal effects found on her body at the murder scene. This comprehensive list includes everything from her red gauze neckerchief to the linen rags in her pocket. What the inventory doesn’t include, though, is a shawl. As any museum curator or art dealer will affirm, documentation authenticates an object. Without it, any claims of ownership or identity don’t bear scrutiny.

But none of this has put off avid collectors of Ripper paraphernalia, one of whom paid £22,000 for a postcard thought to be from the killer. Shortly after the DNA story appeared, the owner of the shawl put it up for sale for $4.5 million.

Facts have never stood in the way of the telling (and the believing) of a good yarn.