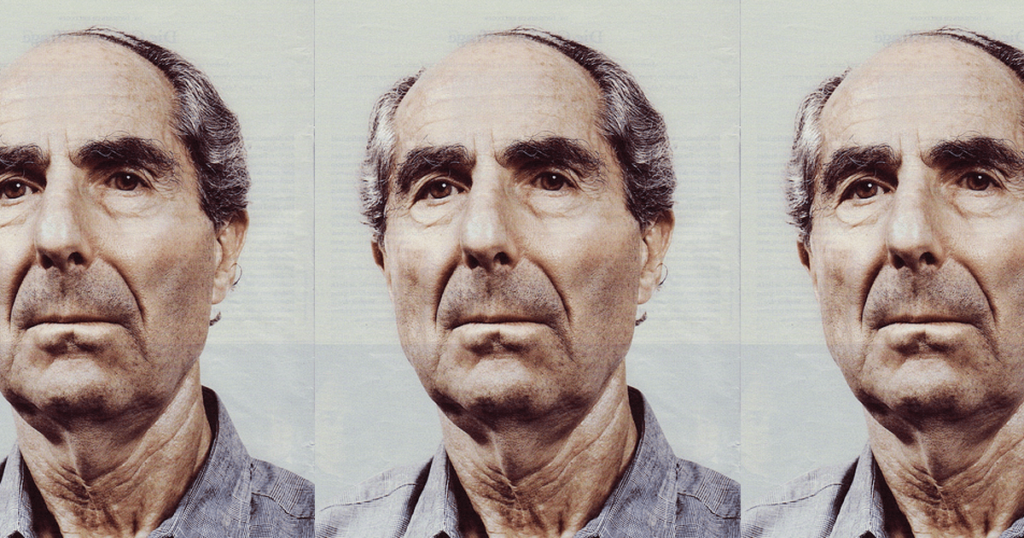

Philip Roth has said that among his literary inspirations were three of his father’s favorite conversational subjects: “Family, family, family; Newark, Newark, Newark; Jew, Jew, Jew.” These were the basic ingredients of the characters and caricatures invented by Roth’s novelistic intellect and animated by his vivacious humor. For those who have read Roth over many years, as I have, his signature originality, authenticity, and style made him someone deceptively familiar, even familial. When anyone is so deliciously funny, most of us feel close, welcomed. As Roth took the measure of our times, he also became a beacon, poised with purpose. When it came to the terrains of the libido, self-delusion, embitterment, and waning powers, he fearlessly charted the minefields of the psyche.

The published obituaries, appreciations, and revived interviews since his death on May 22 have been up to the task, especially by summoning Roth’s own voice. Many such pieces noted the marking of an era, a curtain closing on the likes of Bellow, Updike, and Roth, with nods to Mailer and Tom Wolfe. For these large literary lights, maleness was a way and a means, in contrast to those who deem it a regretful anachronism, as if half the world no longer remains, with its quests and tests, feverish adolescences, anguished adult loves, and storied prostates.

The high regard, the cautions, and the critiques of Roth have long been with us. Except for the Nobel literature committee, which pointedly and smugly ignored him, his admirers know where Roth’s claims are the strongest. The Swedish eminences have now so soiled themselves with allegations of sexual assault that no award will be given this year, a small irony and even smaller justice. Their woes, however, are the kind Mickey Sabbath, from Roth’s National Book Award winning novel, Sabbath’s Theater, would have relished.

Those of a certain age remember when rock ’n’ roll displaced the Lucky Strike Hit Parade, and the world began anew. Portnoy’s Complaint had that power of sweet subversion and a new pulse. It was if Lenny Bruce had become a novelist. In 1969, when Portnoy was first published, I gave a copy to Mayor John V. Lindsay, my boss, mindful that it was the fictional New York City Assistant Commissioner for Human Rights, Alexander Portnoy, who was serviced by the Monkey in Gracie Park only a few hundred feet away from Gracie Mansion, where New York’s mayors live. Years later, I told Lindsay that Swede Levov, the handsome, burdened hero of Roth’s 1997 American Pastoral, was mistaken for Lindsay himself in the novel in a scene at a Mets game.

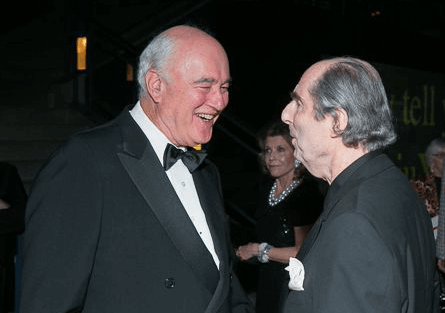

In 2006, I was at a luncheon at the Century Association in honor of Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. I went up to speak to him before the ceremony began, and as I moved on, someone who looked familiar approached to greet him. It was Roth. After the lunch was over, a friend and I worked our way over to introduce ourselves. Roth was relaxed and friendly, in no rush to leave. I told him about the Lindsay connections to his work. Roth said with a smile that when he attended Bennett Cerf’s funeral, “Lindsay stared at me.” I told him I had spent the last few days reading essays on American Pastoral from students at the University of Texas at Austin in my course on the novel that ran from George Eliot to him. He perked up: “Did you have any especially good essays?” I said there were five or six I’d have been proud to put my name on. He took out an envelope and wrote his home address on it and said, “Will you send me copies?” When I got back to Austin, the students, even those whose essays weren’t picked, were delighted that their name-dropping teacher had brought Roth even closer into their lives.

A few years later, I became the executive director of PEN America, the literary human rights organization. One day I got a call from Roth asking if we could have lunch. He had something he wanted to discuss. We met at Gabriel’s, near Columbus Circle. Roth said he had sprained a muscle in his neck and asked me to please sit facing him, rather than to his side. It added to the intensity of the meal because his look was unwavering, especially when I disagreed with him on one matter about the PEN/Saul Bellow award for lifetime achievement in fiction. Sustaining the place and caliber of the award meant a great deal to him. He made me repeat my reasons for differing with him. Right away, I sensed that I must answer him firmly and clearly—no padded language would be accepted. He listened carefully, giving no clue to his thoughts. For that part of the lunch, I was on edge. (Several days later we came up with a happy resolution to our difference.)

As we walked home up Broadway toward our respective apartment buildings, just a few blocks apart, I told him about my son, his writing, and his ad agency, as well as his very hip T-shirt company with catchy logos. Roth said with a note of happy coincidence, “My brother, Sandy, worked in advertising and once had a T-shirt company.”

In some way, throughout the lunch and after, Roth, although himself a younger brother, felt to me like a hugely accomplished older brother: attentive, good spirited, even expansive, yet absolutely in control of every word he spoke. No waste, no fat. When I came home I was so excited that my wife, Barbara, said it sounds as if you met God. I said, Well, no, but it was close.

A few years later, I was back to teaching and I wrote Roth about my course about fathers and sons. I told him that I had reread his 1991 memoir Patrimony with “renewed reverence” and “differing perspective” as I had grown older. It has a rare combination of valor and tenderness in its expression of filial duty and honesty. He wrote back thanking me for my “generous words,” and asked for my reading list. After receiving it, he wrote to suggest I read Simone de Beauvoir’s “splendid book about her mother,” An Easy Death, and Kafka’s Letter to His Father.

In late March of this year, I sent him a piece I had written about the First Amendment and free speech on campus that opened with a phrase borrowed from him. I wished him a belated birthday and added, “Lead on, I am seven years behind you.”

I was thinking of him several days ago because the Summer issue of The American Scholar will carry a reminiscence I wrote about the year 1968 and the Robert F. Kennedy campaign, for which I worked. The exposed nerve endings of that year were those at the heat and heart of American Pastoral. My writing about 1968, a time when I was in my late 20s, reminded me that Roth had written of his 20s in an essay called “Juice or Gravy.” “I was about to manufacture a future, my future,” he wrote, “though without the least idea that it might well be the future that would be manufacturing me.” I’d been hoping to drop off a copy of the magazine at his apartment building.

That wasn’t to be. When I learned of his death last week, I read again his response to the email I had sent him in March. It ends: “Thanks for the first amendment piece. I’ll read it tonight. Don’t worry a bit about the seven years. They pass like that.”