The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War by Andrew Delbanco; Penguin, 464 pp., $30

Try as they did to define people as property, early American slaveholders knew that the enslaved had volition. Not surprisingly, various measures over the decades required that bonded laborers be restored to their owners, but although many people supported these laws, others resisted them. Runaway slaves forced Americans to take sides. As Andrew Delbanco shows in this wide-ranging, thought-provoking volume, slaves who sought to self-emancipate via escape transformed the law, politics, and culture of the United States in the decades between the Revolution and Civil War.

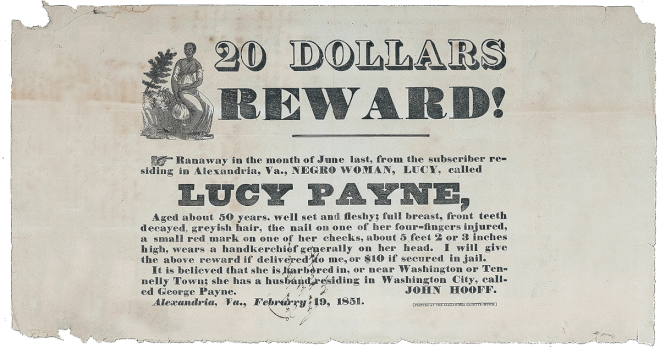

Delbanco, a distinguished scholar and literary critic at Columbia University, opens by considering a twofold problem: how to resolve the antagonism between advocates and opponents of slavery, and what to do when law and conscience diverge. The Founders compromised on slavery, and one of their agreements was the mandate in Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, which stated that persons held to labor in one state who escaped to another “shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.” (Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, for example, advertised for the return of their runaways.) The clause’s passive-voice construction, however, left much uncertainty. Who would do the delivering? The states? The federal government? Bounty hunters?

A 1793 law attempted to clarify the process but only deepened the animosity between slaveholders and abolitionists. It fined anyone who hindered the capture of runaways, thus punishing Northerners for refusing to comply; did not provide legal counsel for fugitives; and did nothing to prevent the seizure and de facto enslavement of free blacks. But Southerners too were unhappy, dismayed that only the governor of the state from which the slave had fled, but not any federal official, could authorize agents to travel north in pursuit of their prey.

In the 1830s and ’40s, many northern states passed personal liberty laws that sought to provide accused fugitives with legal protections. In 1842, a challenge to these laws reached the Supreme Court after a Maryland man who abducted a runaway slave was charged and convicted under a Pennsylvania statute for kidnapping. To the alarm of antislavery forces, Justice Joseph Story ruled in Prigg v. Pennsylvania that a law preventing the removal of runaways out of state was unconstitutional. Fugitives had lost the protections afforded by northern states. At the same time, Story held that local officials could choose whether to cooperate with rendition efforts, and state legislatures began to pass new laws that prohibited officials from detaining anyone charged under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793.

One of the ironies of the secession crisis was that southern states seceded, in part, over the refusal of northern states to adhere to federal legislation. By then, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which had replaced the 1793 law, had been in effect for more than a decade. Passed as part of a series of compromise measures following the Mexican War, the law, for the first time in the nation’s history, put the federal government in the business of recovering runaway slaves, penalized state officials who did not cooperate, and levied heavy fines on anyone who interfered. Numerous reports of captured fugitives filled the newspapers—at least 67 runaways were arrested in 1851 alone. Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, and James Hamlet, to name only a few, became well known, but perhaps none had the influence of Anthony Burns, who was seized in Boston, the center of abolitionism. As thousands watched helplessly, federal troops marched Burns to the harbor, where he was transported to Virginia. Amos Adams Lawrence, a prominent Boston merchant, wrote, “We went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs & waked up stark mad Abolitionists.”

Delbanco emphasizes how cases such as these turned “slavery from an abstraction into an actuality.” The vast “transatlantic literary project”—slave narratives, novels, poems, and theatrical performances featuring the stories of fugitives—also helped awaken moral sensibilities. These are not necessarily the works we remember today, and Delbanco indicts “the major antebellum white writers,” most of whom, with the exception of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Herman Melville, ignored slavery. (One of the pleasures of this volume is tracking Delbanco’s numerous references to Melville’s work.)

Of all the books, none was more important than Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). A direct response to the Fugitive Slave Law, it included an account of a slave mother running away with her child. At one point, the narrator addresses the reader directly: “If it were your Harry, mother, or your Willie, that were going to be torn from you by a brutal trader, tomorrow morning … how fast could you walk? ” In its first year, the book sold 300,000 copies. Long after the Civil War ended, the fugitive slave remained a fixture of American literature, as exemplified by Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) and Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987).

Congress finally repealed the Fugitive Slave Law in June 1864, but its existence had challenged Americans to consider their obedience to the rule of law when it came into conflict with morality. Abraham Lincoln hated slavery, but while running for president, he called for enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law. As he wrote in an 1855 letter to his friend Joshua Speed, a slaveholder, “I confess I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down … but I bite my lip and keep quiet.”

In time, Lincoln found his voice, just as Delbanco invites readers to find theirs. Commenting on 19th-century writers, he notes that “their versions of the past reflected their preoccupations in the present.” Delbanco is not shy about analogizing to present concerns, whether state comity with respect to same-sex marriage, opposition to gun control laws, the problem of mass incarceration, or the treatment of refugees at our borders. The past does not exist to reassure us, but to discomfit us. Delbanco’s most important contribution may be his reminder that “the moral problem of how to reconcile irreconcilable values is a timeless one that, sooner or later, confronts us all.”