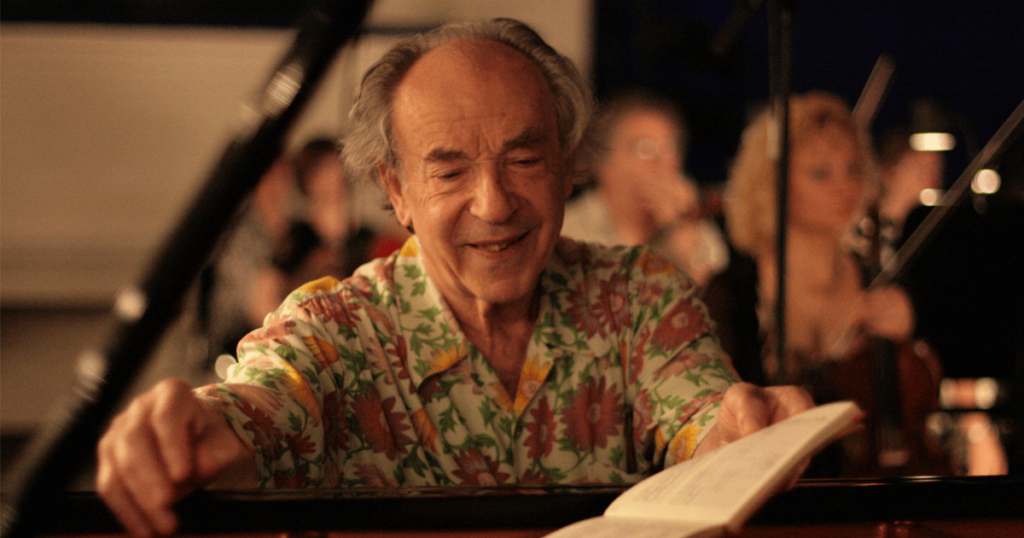

Tomorrow, Paul Badura-Skoda, the venerable poet-philosopher of the keyboard, turns 90. Still active as both pianist and conductor, he has enjoyed a career remarkable not only for its longevity but also for its musical integrity. Few other artists have brought such a keen scholarly apparatus to bear upon so many works, especially those of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. Among the more than 200 recordings that Badura-Skoda has made (is any discography larger than his?) are multiple versions of Mozart’s 18 sonatas, Beethoven’s 32, and Schubert’s 23, performed on both modern and period pianos. He could well be considered the father of the period instrument movement—even if his interest in 18th- and 19th-century keyboards, and authentic instrumental sound, happens to predate the movement by some time, going back as far as the 1950s. Yet he is as eloquent and persuasive on a modern grand as on a historic fortepiano, and his repertoire is by no means limited to the Viennese classics. He has made compelling recordings of, among other composers, Chopin and Ravel, Frank Martin and Alban Berg.

Born in Vienna, Badura-Skoda completed his conservatory studies in 1948. That year he began lessons with the artist who would leave an indelible mark: Edwin Fischer, the Swiss pianist and peerless interpreter of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. In a 1960 essay, another of Fischer’s disciples, Alfred Brendel, set down his own memories of the master:

Fischer was electrifying by his mere presence. The playing of timid youths and placid girls would suddenly spring to life when he grasped them by the shoulder. A few conducting gestures, an encouraging word, could have the effect of lifting the pupil above himself. When Fischer outlined the structure of a whole movement, the gifted ones among the participants felt they were looking into the heart of music.

The gifted Badura-Skoda was no timid youth, and until Fischer’s death in 1960, he continued to absorb his mentor’s musical ethos—not just how to produce a round, full-bodied sound or bring out the voices in a dense contrapuntal passage, but how to penetrate the depths of a score, by stripping out the errors of careless editors and getting to the core of a composer’s original intent. Sure enough, if you listen to Badura-Skoda’s live 1962 performance of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue, you can hear certain similarities with Fischer’s wondrous account from 1931: the sense of reverie, invention, and improvisation in the arpeggiated lines; the wide range of tone colors, with the sound plush one moment, bell-like the next; the ability to move from darkness to light, through a judicious use of pedaling and attack, in the course of a single phrase.

In 1950, Fischer was due to play a trio recital with his colleagues Wolfgang Schneiderhan and Enrico Mainardi at the Salzburg Festival, when he fell suddenly ill. So Badura-Skoda stepped in. He was 23 years old, and though he had already appeared as a soloist with such eminent conductors as Wilhelm Fürtwangler and Herbert von Karajan, he came to the attention of the world that August day in Salzburg, playing the Piano Trio No. 1 by Brahms. Soon, he was making the first of his recordings and embarking on a lifetime on the concert stage, as a soloist and as a genial collaborator with such artists as the violinist David Oistrakh and fellow pianist Jörg Demus. With his wife, the musicologist Eva Badura-Skoda, he published studies on Bach and Mozart, while training the next generation of pianists as a highly esteemed teacher. In short, he has had the most catholic of careers, equally prominent in the fields of performance, scholarship, and pedagogy.

In less than two weeks, in the Great Hall of the Musikverein in Vienna, Badura-Skoda will perform a birthday recital. It’s an all-Beethoven program: the Six Bagatelles, opus 126, and the last three sonatas, opera 109, 110, and 111—a daunting enough challenge for any pianist, let alone one entering his 10th decade. If you can’t make it to Vienna the night of October 15, you can get a sense of the Badura-Skoda magic by listening to a recording he made of those three Beethoven sonatas, in December 2013. The catalog has no shortage of great performances of these towering works, yet even among the crowded field, these recent Badura-Skoda recordings are notable for their songfulness, their spirituality, their refinement and subtlety. He imbues the opening movement of the opus 109 sonata with the same sense of fantasy that he brings to his Bach, and the exquisite theme and variations of the third movement sound at once noble and tender, with an ending tinged with melancholy. His opus 110 is commanding, majestic—just a single line here, almost any line, is a master class in shading and color—and heartbreaking in the plangent slow movement, the instrument singing like a human voice calling out from the depths of despair. Listen, as well, to the way he strikes the notes of the bass line in the fugue that closes the sonata: the sonorities seem almost reminiscent of a historical piano, not the modern Steinway upon which he’s performing—an act of pure alchemy. With Badura-Skoda, perhaps more so than with any other pianist, we become attuned to the characteristics of the different instruments that he plays, noting the clear, bright sound of the Bösendorfer he uses for the opus 109 and the fuller, larger sound he coaxes out of the Steinway in opera 110 and 111.

Badura-Skoda’s apocalyptic reading of Beethoven’s final sonata, the opus 111, begins with the widening of some horrifying abyss, the feeling of tragedy only temporarily lightened by the fleeting appearances of the movement’s glowing, gentle second theme. Everything leads to the saintly melody of the Arietta, and here, and in the transcendent variations that follow, we hear in Badura-Skoda’s performance the promise of benediction, of ultimate consolation.

Long may his career continue. (As it happens, pianists seem to thrive well into very advanced age, long after their counterparts on the violin and cello have put their instruments down.) Nearly seven decades after his debut, he continues to fulfill the dictum of his mentor, Fischer, that the pianist must “put life into the music without doing violence to it.” In a world where too many pianists seem intent only on showing themselves off, preening before audiences and emoting to the heavens, Badura-Skoda is also that welcome rarity: the artist who puts the composer first and the ego of the performer second.

Listen to Paul Badura-Skoda, at the age of 86, play the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 32, opus 111: