The Silent Candidate

In 1860, after Lincoln received the Republican presidential nomination, he kept his mouth shut until the election—we should be so lucky today.

After making a sensational debut in New York City in February 1860 with a history-changing address at Cooper Union, Abraham Lincoln planned to head north for a reunion with his eldest son, Robert, a student at the Phillips Academy at Exeter in New Hampshire. As news reached New England Republican leaders, invitations quickly poured in: Lincoln was asked to speak at 14 additional venues. He accepted 11, at each of which he went on to deliver a triumphant reprise of the Cooper Union address—an oration that became known as “the speech that made Lincoln President.” It’s far more accurate—and what better time and place to say so—to remember that all these 1860 speeches made Lincoln president, and that Lincoln well knew their significance.

Yet for generations, legend held that Lincoln accepted the New England engagements reluctantly. After Cooper Union, the story goes, he wanted nothing more than to rest up and visit his son. He agreed to speak only to help out local Republicans. And since lusting for office was not considered a virtue, Lincoln fueled the myth. Words like weary and toil crept into his correspondence from the road.

Eventually, biographers bought in. One, Elwin Lawrence Page, went so far as to argue that “there was not more than a secondary thought of self” in all of Lincoln’s New England speeches. Well, as Lincoln once said, you can fool some of the people all of the time—even historians. Such naïve appraisals woefully underestimate Lincoln’s political acumen and ambition.

The truth is, Lincoln toured Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire for one reason: to pick off delegates to the upcoming Republican National Convention by proving in New England, as he had in New York, that a western-style stump speaker could hold his own in Yankee country. His eyes were firmly fixed on the White House. And the road to the White House, then as now, ran through New Hampshire.

How did he do here? Sadly, no transcript survives of his first speech, at Concord. But the local Republican newspaper did praise what it called Lincoln’s “irresistible logical force and power.” In Manchester, the Daily Mirror reported that Lincoln displayed “more shrewdness, more knowledge of the masses of mankind, than any other public speaker we have heard.” In Dover, he spoke for nearly two full hours, and “would have held his audience,” said the local paper, “had he spoken all night.”

My favorite New Hampshire recollection came out of Exeter, from one of Robert Lincoln’s school chums. Like a typical teenager, Robert was embarrassed about having his sophisticated pals meet his rustic dad. At first glance, for good reason. When Lincoln appeared on stage at Town Hall, one of those friends caustically observed: “His hair was rumpled, his neckwear was all awry, he sat somewhat bent in [his] chair, and altogether presented a very … disappointing appearance. … We sat and stared at Mr. Lincoln. We whispered to each other, ‘Isn’t it too bad Bob’s father is so homely? Don’t you feel sorry for him?’”

But, as the eyewitness admitted, once Lincoln “untangled those long legs,” “drew himself up to his full height,” and launched into his speech, “not ten minutes had passed before his uncouth appearance was absolutely forgotten by us boys. … His face lighted up and the man was changed; it seemed absolutely like another person speaking to us … There was no more pity for our friend Bob; we were proud of his father.”

Such appraisals echoed from one New Hampshire town to the next—always beginning with shock at the initial sight and sound of Lincoln. He was “grotesque” and “uncouth.” His ears stuck out, his hair was unkempt, and his voice and accent were hard to understand. But somehow, after 10 minutes on stage—the magic always seemed to happen at the 10-minute mark—Lincoln began hypnotizing his listeners. Observers recalled that “his eyes glistened with the fervor of his own enthusiasm, the lines of his homely face disappeared,” and his wit “cut like a Damascus blade.”

To be sure, not every observer fell under his spell. Newspapers of the day were creatures of political parties, and Democratic journals had nothing good to say about the Republican visitor. One even charged that Lincoln wanted to substitute Nashua as a venue when Manchester offered him only $50 to talk, half the fee the greedy orator demanded. Yes, Lincoln aroused controversy that election year because he had taken big honorariums for his speeches. Some things never change.

Often the partisan criticism was far more personal—and provocative. Another opposition paper actually claimed that in one speech, “Mr. Lincoln apologized for the slovenliness of his personal appearance, and for not having even changed his linen,” then proceeded “to enlighten the people in New England with regard to the superiority of the African race over that of the Anglo-Saxon.”

Of course, Lincoln did neither. What he advocated was refusing to call slavery right when it was wrong. And he proposed to confront it by banning its spread into the western territories in order to place slavery on “the course of ultimate extinction.” Yet to one New England Democratic paper, that restriction alone was a recipe for secession. Opposing slavery in any shape or form, it warned, would split the Union into pieces, “baffling the skill of our modern Republican artists to combine [it] again.”

This challenge to artists makes an imperfect but irresistible transition to a crucial chapter in the story of Lincoln’s 1860 visit to New England. Remember: as much as his appearance may have startled his audiences, Lincoln knew better than his contemporaries how homely he was. Accused in a debate once of being two-faced, he replied: “If I had another face, do you think I would wear this one?”

Such self-deprecating stories fill the Lincoln literature. My favorite is another he told on himself. Riding alone in the woods one day, he came upon a hideous-looking fellow who lifted his rifle and aimed it right at Lincoln’s chest. “Stop, my friend, what on earth are you doing?” asked Lincoln. “Stranger,” the man replied, “I always vowed that if I ever met a man uglier than myself, I would shoot him on the spot.” To which Lincoln replied: “Friend, if I am uglier than you, then fire away!”

What is remarkable about such stories is not just that Lincoln was secure enough to make fun of himself. What should truly amaze us is that, even while mocking his own appearance, he was simultaneously making sure it was being captured and distributed by artists in all media. He may later have joked, “I cannot see why all you artists want a portrait of me, unless it is because I am the homeliest man in Illinois.” But he uttered those words to a gaggle of painters who had set up their easels side by side to make his likeness.

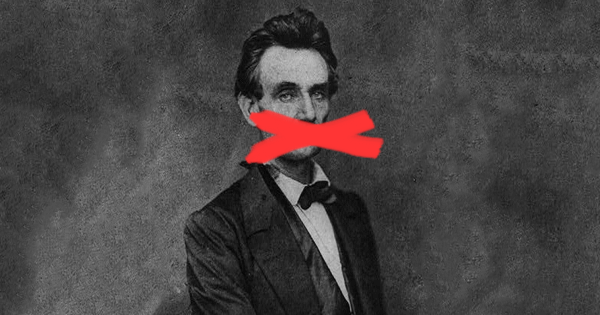

The trend started even earlier. Just hours before taking the stage at Cooper Union, Lincoln visited the studio of photographer Mathew Brady. There, he posed for a likeness that proved as important as the speech in propelling his candidacy. “Brady and Cooper Union,” Lincoln later agreed, “made me president.” Indeed, the photo was reproduced in prints, posters, badges, banners, and broadsides so often that it came to serve as a surrogate for the candidate. Why? Because after delivering his final New England oration in March 1860, Lincoln gave not a single additional speech during the entire campaign to come. Like openly partisan newspapers, a candidate’s self-imposed silence is another vanished tradition from the Lincoln era. How many of us wish that tradition existed today?

What, then, was an incurable campaigner to do in a political environment in which personal appearance was important, but personal appearances were forbidden? The answer: “appear” before the people through photography, art, and sculpture. And that was exactly what Lincoln did once the tradition of not campaigning stilled his powerful voice.

Only a few weeks after returning from New England, he visited the Chicago studio of sculptor Leonard Wells Volk, where he sat for a life mask—a process so disagreeable, Lincoln recalled, that it required him to insert straws in his nostrils so he could breathe while wet plaster was slathered over his face. After the plaster hardened, Volk tried to ease the mask off his subject’s face—without success. It clung fast. Lincoln had to use his own strong hands to ease the mask away, tearing out hairs from around his temples and drawing involuntary tears from his eyes.

Yet the following month, he obligingly returned to Volk’s studio, this time to sit for a bust portrait. And he stayed even after Volk surprised him by asking him to shed his coat and vest, remove his shirt and tie, and pull down the Union suit he wore underneath, so the sculptor might capture what he called “his breast and brawny shoulders.”

How did Lincoln react to that request? So embarrassed was he that the minute the sitting ended, he quickly dressed and fled into the street. He had walked several blocks before a passerby alerted him that the sleeves from his underwear were dangling from his coattails and trailing along the sidewalk. Lincoln had to sheepishly return to Volk’s workshop to dress once again.

But the result proved well worth the ordeal. When Lincoln first glimpsed the finished bust, he burst out to Volk: “There is the animal himself!”

Still more was to come. In mid-May, right after Lincoln won the Republican nomination for president, Volk showed up in the candidate’s hometown to ask him to submit to new plaster castings—this time, of his hands. Volk now proposed a full-length, life-size statue of the nominee like the one he had once produced of his cousin-in-law, Lincoln’s longtime political rival and now his presidential opponent, Stephen Douglas. Volk wanted to depict Lincoln holding a scrolled document.

But Lincoln’s right paw was swollen from a long night of congratulatory handshaking. To mask the puffiness, Volk suggested that Lincoln grip some object. The candidate retreated to his back yard, and Volk soon heard the loud sound of a saw cutting through wood. When Lincoln reappeared, he was whittling away at the stump of a broom handle he had amputated outside. Please don’t bother, Volk quickly said. The ends don’t have to be smooth. It’s only a prop. “Oh well,” replied a disappointed Lincoln. “I thought I would like to have it nice.”

Overall, as a subject for artists, Lincoln had it even nicer than he deserved. During that summer, fall, and winter—as busy as he became pulling the strings to run his White House campaign from behind the scenes, as hard as he later began toiling to confront the secession crisis that greeted his victory—Lincoln consistently made himself available to photographers, painters, and even another sculptor. He knew people wanted and needed to see him, especially after he grew a beard.

Volk’s mask and hands later inspired and informed Augustus Saint-Gaudens in modeling his own incomparable sculpture of Lincoln. As a teenager, Saint-Gaudens had seen President-elect Lincoln in life, recalling a “very dark man” bowing from his carriage. Five years later, Saint-Gaudens saw him again in death, lying in state inside New York’s City Hall, now a martyr to liberty and freedom, still so compelling that the young man waited in an endlessly long line to glimpse the remains, then rushed to the back of the queue so he could study the late president again.

He is still worth studying. When Lincoln spoke in New England in 1860, he did not advocate political revolution. He was too realistic politically. He understood the process too well. He knew slavery was enshrined in the Constitution, and that its advocates would cling to that guarantee, perhaps to the death.

Of course, slavery was an evil, he argued—but one that he believed could only be eradicated gradually, for fear of destroying the Union. He explained his position through homespun metaphor: to favor immediate abolition would be as dangerous as excising a malignant tumor, but allowing the patient to bleed to death. Or like finding a venomous snake in your children’s bed, but striking at it so reflexively that the snake fatally bites the children before dying.

Disdaining upheaval, Lincoln advocated gradual change: for now, leave slavery alone where it had long existed, but choke it off completely from further expansion. Forbid its spread. Wait for new western territories to organize as free states and then send anti-slavery senators and congressmen to Washington. When they achieved the super-majority needed to amend the Constitution, slavery would end. Until then, never let the advocates of slavery forget that their position was morally wrong, and the opponents of slavery right. That was the essence of Lincoln’s New England message.

One of the supreme ironies of history is that even Lincoln’s moderate approach—just as that New England newspaper predicted—aroused such violent opposition in the South that the mere fact of his election provoked secession, the conciliatory reassurances of his inaugural address being insufficient to prevent rebellion.

In a sense, then, Abraham Lincoln became a hero in spite of himself. The homely, self-effacing giant made sure that the visual arts introduced him to voters and enshrined him as an American icon. The instinctively cautious politician proved willing to sacrifice a staggering 750,000 lives in order to save American democracy and secure a new birth of freedom.

Some of the ideas Lincoln fought and died for took final shape in New England. He went further than at Cooper Union—making stronger anti-slavery attacks, and arguing for a working man’s right to advance up the ladder of opportunity. Between speeches, he visited Manchester’s Amoskeag textile mill, where he came face to face with a harsh reality: that free men in the North sometimes profited from cotton harvested by enslaved men in the South. The horror he felt took shape later, in his Second Inaugural, in which he described slavery as an “offense” for which North and South alike were guilty.

And during his New England visit, Lincoln openly supported striking local shoe-workers, declaring: “I am glad there is a system of labor where the laborer can strike if he wants to.” Without it, “slavery comes in, and free labor that can strike will give way to slave labor that cannot!” What made America truly free, he said, was its promise of opportunity, giving “the humblest man an equal chance to get rich with everybody else. When one starts poor, as most do in the race of life, free society is such that he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor for his whole life.” Here was Lincoln’s response to income inequality: a fair chance in the race of life.

Lincoln came to New England in March 1860 with almost no chance of changing longtime political allegiances. Yet when convention votes were cast in May, enough local delegates went over to Lincoln on the second and third ballots to help put him over the top and make him the nominee. For all the press hoopla of his Cooper Union triumph, not a single New York delegate ever switched from William Seward to Abraham Lincoln; they remained united as a bloc for their favorite son. In New Hampshire, in Connecticut, his oratory moved votes. And he went on to win all the states along his speaking tour come November.

Perhaps those defections meant that listeners, and their convention delegates, recalled and appreciated that wherever he had gone on his New England tour—from Connecticut to Rhode Island to New Hampshire—Lincoln closed his speeches with a rousing version of the same words he had introduced to climax his address at Cooper Union—always, an eyewitness remembered, greeted by “the wildest enthusiasm.” Words well worth remembering today:

Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the government nor of dungeons to ourselves. Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.

In dedicating an earlier bronze statue of a standing Lincoln in Washington in 1876, the great abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass remembered the right behind Lincoln’s might, and, speaking for many of the freedmen who had financed its casting, urged Americans to “multiply his statues, to hang his pictures high.”

Amid the venom of a modern political campaign in which both candidates have quoted and identified with Lincoln (and yet a campaign that is so notably devoid, at least on one side, of “malice toward none, charity for all” and other Lincolnian sentiments), we should recognize here in Cornish that the best way we can honor the greatest of our presidents, and the greatest of his statues, is by remembering—again and always—that a house divided against itself really cannot stand. Binding up the nation’s wounds, not rubbing salt into them, should be a national aspiration. And we should recall the adage with which Lincoln concluded all of his 1860 speeches: right really does make might, and not the other way around.

This piece is adapted from an address given in June at the unveiling of the Standing Lincoln statue at the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, New Hampshire.