The Most Wanted Man in China: My Journey from Scientist to Enemy of the State by Fang Lizhi; translated by Perry Link; Henry Holt, 331 pp., $32

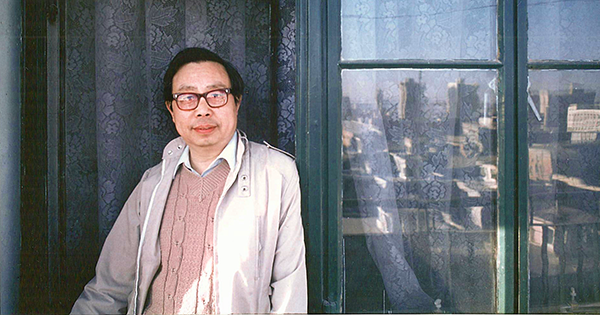

Many Fangs appear in The Most Wanted Man in China: My Journey from Scientist to Enemy of the State, a compelling memoir by Fang Lizhi (1936–2012). We meet Fang the well digger, Fang the farmer, and Fang the reluctant bureaucrat, but there are three other Fangs whom we get to know best and care about most. One of these is Fang the astrophysicist, whose thirst for knowledge about how the universe works is never quenched and who believes that scientific modes of thought can be used for ethical and political questions.

The second is Fang the dissident, whose rejection of the revolutionary faith of his youth puts him on a collision course with the ruling Communist Party. The collision happens with the massacre near Tiananmen Square of June 4, 1989, which Fang describes aptly as an event that found the People’s Liberation Army, welcomed into the capital by Beijing’s citizens in 1949, storming into this same city as an invading force ready to assert its domination over the populace.

The last of the three Fangs is the devoted husband. We are introduced to his wife, Li Shuxian, when she and Fang are young students of physics who meet in the university library lobby after their evening studies and share a chaste walk and passionate conversation on the paths of a darkened campus. She becomes his lifelong partner in professional and political life as well as personal ventures. Their marriage survives two generic challenges faced by many Chinese intellectual couples of their generation—long periods of separation, during which Fang labored in the countryside, and the vicissitudes of paranoia-fueled campaigns against alleged Party enemies—and a unique one: living in close quarters for a year in a windowless room inside the American embassy in Beijing. Their period of hiding began when they were granted political asylum the day after the June 4 massacre but could not end until negotiators found a way to reconcile Fang’s belief that he was innocent of wrongdoing and the party’s insistence that he admit to having been a “black hand” who led impressionable youths astray during the Tiananmen protests.

Fang peppers his accounts of major events with asides about the beauty of theoretical astrophysics and the rhythms of daily life during the Mao years. His vignettes and ruminations are rendered into lively, fluid English by translator Perry Link, a leading scholar of Chinese literature who was a close friend of the scientist and an eyewitness to some events featured in the book. Most notably, in early 1989, Link and his wife accompanied Fang and Li during a tense evening spent trying, unsuccessfully, to get to a Beijing barbecue hosted by the visiting American president George H. W. Bush, to which they had all been invited. China’s leaders were determined that Fang, by then the most influential dissident in the country, should not attend.

Reading Fang’s memoir reminds us that China, for all its materialistic striving and authoritarian control, is a place where humor and laughter abound, where you hear plenty of jocular banter and kidding around. Take, for example, the Chinese government’s efforts to control the Internet and to prevent all discussion of the Beijing massacre, and indeed ban all mention of the date on which it took place. This is a very serious matter, but you cannot hope to have a full sense of 1989’s aftermath without considering the creative and humorously subversive forms of mockery and wordplay that those determined to speak their minds have used. My favorite case in point is the digital calls, which proliferated until the censors realized that they were being had, for people to remember what transpired on “May 35th,” a date that stood in very nicely for the real one whose mention was verboten.

When Fang’s name is mentioned, the words likely to spring to mind are serious ones: “hero” and “truth teller,” if, like me, you admire him; “traitor” and “conspirator,” if you accept the Chinese government’s line on him. It is worth noting, though, as Link stresses in his epilogue, that Fang’s attributes included a “puckish wit,” and this quality is on display throughout the book. He wrings a great deal of humor, for example, out of the increasingly absurd lengths to which the authorities went, over the course of that evening in early 1989, to keep two middle-aged couples from attending the Beijing barbecue, presenting the various measures the party took as if they were plot points in a cross between Keystone Kops and Mission: Impossible.

The Most Wanted Man in China makes no mention of imaginary dates, but although Fang’s memoir deals with many disturbing subjects, it comes across as a work written by a man who was both animated by a passion for truth and aware that a mischievous May 35th spirit is worth cultivating and celebrating.