The Story of a Stare Down

How two antagonists from Tudor England ended up facing each other on Fifth Avenue

“It seems as though Cromwell has More right where he wants him,” the social scientist Todd Oakley writes in his essay, “Do Pictures Stare?” Many art-loving New Yorkers will immediately get the reference. At the Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue, two portraits by the German artist Hans Holbein the Younger—one of Sir Thomas More, the other of Thomas Cromwell—faced off against each other for years from either side of a majestic fireplace in the hallowed, oak-paneled room known as the Living Hall.

Other visitors to the Frick have doubtless shared Oakley’s impression. It’s fun to imagine that Cromwell glares at More, daggers drawn, at least telepathically. For his part, More—a study in tranquility—stares thoughtfully in Cromwell’s direction. He’s looking into the distance toward his left, at something we can’t see. His expression is pensive, calm, direct.

Created in 1527, this oil-on-panel portrait is so lushly painted it seems to glow. More’s fur-trimmed, emerald velvet cloak looks impossibly lustrous, as does the crimson doublet he wears beneath it. “That sleeve should be illegal,” the writer Jonathan Lethem recently wrote, in a much-quoted line, referring to this garment. There are two sleeves, actually, each one hyperreal. You want to reach out and caress them.

One the other side of the mantelpiece, Cromwell peers, slit-eyed, to his right—that is, in the direction of More’s portrait. Both subjects sit at an angle, looking beyond the picture frame. Cromwell, though, resembles a creature that’s withdrawn into its shell. He looks wary, hunted, alone. “No one has ever suggested that it is an endearing picture,” his biographer Diarmaid MacCulloch has written. How could one? Still, there’s a hint of vulnerability here, something rueful in Cromwell’s expression. He seems conflicted. Human.

As lawyer and chief minister to Henry VIII, Cromwell rose through the ranks by doing his king’s bidding. The rewards were ample. At the time Holbein painted this work, in 1532–33, Cromwell had just been named Master of the Jewel House, in appreciation of the role he played in orchestrating the English Reformation. He would climb consistently higher, becoming Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lord Privy Seal, King’s Secretary, Master of the Rolls, and Lord Great Chamberlain, among other titles in the years ahead.

A devout Catholic, More incurred the king’s wrath by defying his plans to replace Catholicism with the new Church of England, a move that would free the sovereign to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, to marry Anne Boleyn. Acting on Henry’s orders, “Cromwell became the chief agent in [More’s] destruction,” writes MacCulloch—and then Boleyn’s. After the king’s third wife, Jane Seymour, died in childbirth, Cromwell facilitated Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves—a bride who turned out to have zero physical appeal for the sovereign. This bit of ill-fated matchmaking helped to propel Cromwell toward his own grisly end.

A decade or so ago, those conversant with English history would have likely seen Cromwell as “the brutal sidekick of a brutal king,” as scholar Colin Burrow has written. But thanks to Hilary Mantel, whose nuanced, psychologically acute depiction of the man in her Wolf Hall trilogy (published between 2009 and 2020), this vision of a sadistic Cromwell has been reset. He’s become, almost improbably, a man with a soul.

Thomas Cromwell, Hans Holbein the Younger, 1532–33 (Wikimedia Commons)

Wolf Hall, the first novel in Mantel’s series, opens in the year 1500. The setting is the village of Putney, just southwest of London, where a teenage Cromwell lies face down on the street, having been repeatedly struck and kicked in the head by his blackhearted blacksmith of a father:

“So now get up.”

Felled, dazed, silent, he has fallen; knocked full length on the cobbles of the yard. His head turns sideways; his eyes are turned toward the gate, as if someone might arrive to help him out. One blow, properly placed, could kill him now.

We root for Cromwell from these opening lines.

Mantel takes us deep into his mind, keeping us in surprising sympathy with him, even as he moves purposefully ahead in a pitiless age, forever reminded of his own humble origins by those around him. The later death of Cromwell’s wife and small daughters further endears him to us, as do his frequent, if covert, acts of kindness—often directed toward vulnerable women—and the unfailing tenderness with which his thoughts, brought to life by the seemingly clairvoyant Mantel, return to his late mentor, Cardinal Wolsey. “Once the record stops, that’s where I begin,” the author has said, describing her approach.

Though works of fiction, Mantel’s deeply researched books exude a rare authority. MacCulloch, a lifelong Cromwell scholar, has professed his admiration for her portrayal. Can there be a greater accolade? Her characters, from the mercurial, troubled Henry VIII down to a scrappy, ill-fated youth known as the “eel boy,” so insignificant we never learn his name, are so multifaceted, so richly drawn—and Mantel’s knowledge of Tudor life and mores so detailed—that reading her portrait feels like arriving at the true Cromwell at last.

New Yorkers speak of the Frick Collection possessively, as if it belongs to them, to us. It’s homey, in the literal sense. (That is, if you’re a robber baron.) As you climb the broad steps to this sprawling Beaux-Arts style building, designed by Thomas Hastings of Carrère & Hastings in 1912–14, and pass through its ornate oak front doors, a revivifying sense of well-earned privilege wafts down upon you, a kind of mist. Entitled or not, you become so, swanning through the late Henry Clay Frick’s residence like the treasured guest of a generous, unseen host—albeit one who is not invited to linger, as indicated by tasseled ropes of multicolored silk, elegantly draped across tapestried armchairs.

A few years ago, though, I had an invitation to do exactly that when I had the great, cosmic luck of being awarded a Leon Levy Fellowship to conduct research at the museum’s renowned Frick Art Reference Library. There I joined others who had been given leave, as I had, to climb the stairs to the Scholars’ Balcony with its wrought-iron railing, fill the shelves of our carrels with books, and, from there, wander through art history with access to hundreds of thousands of volumes in one of the greatest art-related libraries in the world.

One of the many unstated perks of this fellowship was the chance it offered to enter the galleries on Mondays, when they are closed to the public. So many enticing distractions! There they all were—Watteau’s soldiers, Ingres’s Comtesse d’Haussonville, Manet’s defunct toreador—and that was in just one short corridor. There were never many people around, beyond a constellation of friendly guards and the occasional member of the collection’s curatorial staff moving purposefully through the space. A film crew might appear or a small, scholarly group on a private tour. Mainly, though, it was just you and the art.

It takes time to stop and absorb these works in the mansion’s vast rooms, time a researcher doesn’t have. Still, there were always minutes enough to linger before just one painting, scrutinizing it for the chance—inevitably realized—of seeing something new in it each time. Like countless other Wolf Hall readers, I felt I’d known the true Cromwell from the moment I first met him, face down and bleeding, on the cobblestones of Putney. I’d stop before his portrait and ponder his coiled expression—part fight, part empathy—wondering which version of the man was true.

In March 2020, the month when Covid-19 arrived, so, too, did The Mirror and the Light, the final volume of Mantel’s trilogy. Perfect lockdown material! Before too long, I was once again immersed in Tudor England—grateful to be in the thrall of such an absorbing narrative while waiting for the virus to disappear.

During the pandemic, my social circle shrank to a tiny few. On summer afternoons I’d wander over to the faculty club of the nearby university with its glorious garden. There, all was as it had been. Except that it wasn’t. The students seemed to have evaporated; we locals—skewing much older—had taken their place. We lolled on the club’s lawn, or hunched over books or gadgets on the benches, savoring the garden’s unfolding beauty, as geraniums, impatiens, four kinds of marigolds (!), and more came into bloom. The sense of escape from our homes, to which we’d been near-universally confined, was delicious.

Even as Mantel’s novel transported me away from our germy season, it dropped me, pitilessly, into another: the bubonic plague, known as the Black Death, which first broke out in Europe in 1347. Dormant when Henry VIII ascended the throne in 1509, it flared up again in London 20 years later. From that point on it returned with grim regularity, arriving every decade or so until the mid-17th century. The math was punishing. There were about 40 outbreaks of plague during this 300-year period; a fifth of the population of London was eradicated each time. (Holbein himself, then in his 40s and still in the king’s service, is thought to have succumbed to it when he died there in 1543.)

Tudor anti-plague rituals, as Mantel describes them, closely resembled the endless sanitizing, masking, and travel-altering routines that characterize our lives today. Snap lockdowns were a regular occurrence. When royalty traveled, specific protocols came into play. Mantel describes ones taken during a 1539 journey:

Every town must be certified clear of plague before the king enters the neighbourhood. At the slightest suspicion, his route must be changed, so there must be extra hosts standing by, their silverware polished, their feather beds aired.

When I read this passage, I, like so many, imagined that Covid-19 would one day neatly end. It was a pleasant fantasy, doubtless fueled by spending hours on a bench in a fragrant utopia. It couldn’t last. As news of Covid variants began to circulate, we learned something that the court of Henry VIII, and likely much of England, once knew—that plague doesn’t neatly leave; it can linger for decades. Perhaps even centuries.

One day—in that book, in that garden—some lines of dialogue stopped me short. They came late in the narrative, just after Henry bestowed an earldom on Cromwell. Being named the 1st Earl of Essex was a signal honor—and a dangerous one. The title brought with it “twenty-four manors in Essex, besides holdings in other counties,” among other privileges and gifts. More valuable still, it conveyed the King’s lasting approval, a rare promise of permanence in Henry’s ever shifting, treacherous court.

It also caused Cromwell’s enemies, already legion, to combust. On June 10, 1540, Cromwell arrived late to what he thought would be a meeting of the Privy Council. His longtime foes, the Duke of Norfolk and the Bishop of Winchester, were waiting, having deftly persuaded the increasingly paranoid Henry VIII that Cromwell was plotting to usurp him. Within an hour he was hauled off to the Tower of London. He would have had few illusions about where he was headed from there.

The dialogue in question came just two days after these events, when a shaken Ralph “Rafe” Sadler, one of Cromwell’s “talented young men” and a trusted ward and advisor, was admitted into his master’s rooms in the Tower. Their conversation was fraught. Two lines, in particular, caught my attention:

“Rafe, what happened to my picture? That Hans made?”

“Helen [my wife] took it, Sir. She has it safe.”

That Holbein! Of course, it was part of Cromwell’s everyday life, too. It was startling to realize that I shared this precise visual experience with the man himself. It was an obvious conceit, yet one that brought me to him with a sudden, surprising intimacy.

Paintings aren’t alive, of course. They can’t see or remember. Yet some have witnessed so much. I began to wonder what Holbein’s Thomas Cromwell might have seen, that is, if it could see. How had it traveled through the centuries, through the worlds between then and now? What had it witnessed as it ricocheted toward the present?

After Cromwell’s imprisonment, the Crown sent a veritable army to Austin Friars—the sprawling mansion Cromwell had built on land that once formerly belonging to an Augustinian abbey. In the 1960s, the art historian Roy Strong, former director of both the National Portrait Gallery in London and the Victoria & Albert Museum, described the scene:

Scarcely two hours after Cromwell had passed through Traitor’s Gate on 10th June 1540 a company of archers under royal auspices descended on the house of the fallen minister to bear away his goods. The movables were taken that same night to the treasury.

Thomas Cromwell vanished then, or just before.

The portrait’s next stop has long been a matter of debate. Noting that it never appeared in a royal inventory, Strong posited that it was destroyed soon after Cromwell was taken into custody, and that all three existing versions of the painting—at the National Portrait Gallery, Burton Constable in Yorkshire, and the Frick—are copies. “None … is acceptable as directly from the hand of Holbein himself,” he asserted.

But other scholars disagree, siding with an earlier verdict by Lionel Cust, director of the National Portrait Gallery in the early 20th century, that there “would be nothing improbable in supposing that Cromwell, then anxious to conciliate his influential friends, had more than one portrait of himself painted by Holbein for this purpose.” In his 1985 book on Holbein, the scholar John Rowlands (no relation to this writer) makes a persuasive case that the Frick portrait is the original:

X-ray photographs have revealed important pentimenti, which indicate a creative hand has been at work. The artist had originally painted the paper held in the sitter’s left hand more to the right and higher, which meant that the sleeve had to be lengthened by half an inch. Such an adjustment is just the sort of change that Holbein makes in other portraits. Although its present condition means that absolute certainty is impossible, nevertheless the presence of these pentimenti makes it well-nigh certain that the Frick version is a badly preserved original.

As for the portrait’s relative lack of depth and detail—notably in comparison with Sir Thomas More—Rowlands attributes it to at least one “ruthless cleaning” that “removed much of the surface subtlety characteristic of Holbein.”

For his part, MacCulloch states matter-of-factly that the portrait at the Frick “seems to have been preserved by the faithful Ralph Sadler, who must have acquired it in the break-up of his master’s house in 1540.” Mantel adopts this same view.

Thomas Cromwell’s next established home was in verdant Hertfordshire, 20 miles from Austin Friars, on the Tyttenhanger Estate, a property that belonged to the Abbey of St. Albans until it was seized by the Crown in 1539. Eight years later, Henry VIII bestowed Tyttenhanger on Sir Thomas Pope who, as treasurer of the Court of Augmentations, had successfully confiscated many such properties. After Pope died of the plague in 1559, the portrait descended, in the parlance of art historians, passing first to his widow and then, after her demise, to a nephew. From there it zigzagged down the years to one Katherine Hardwicke, who married an Earl of Caledon in 1811.

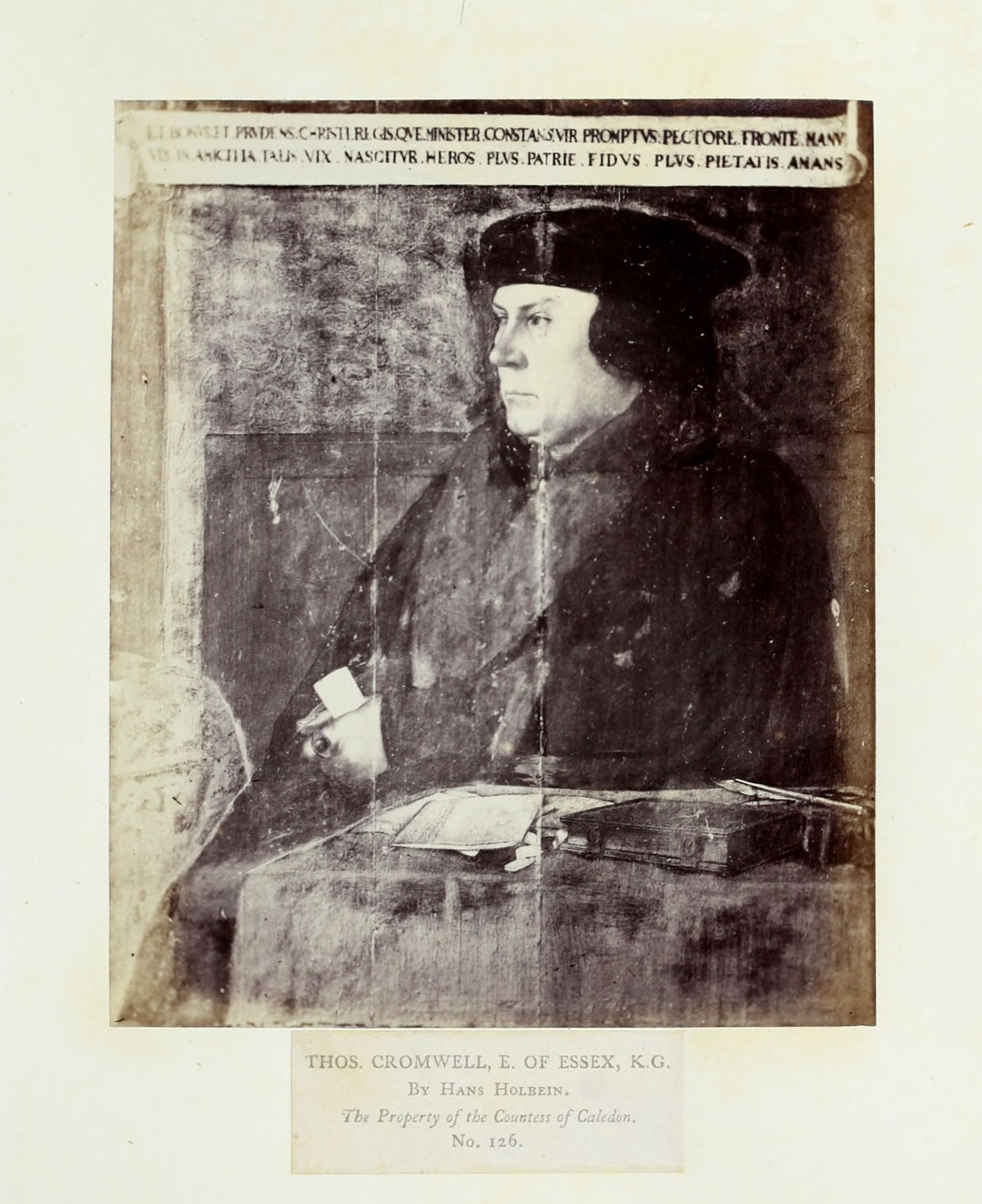

The painting appeared in public for the first time after a later Countess of Caledon lent it to the National Portrait Exhibition, held in London in 1866. A distressed-looking reproduction of the work, included in a tattered exhibition catalog, seems like a forlorn distant cousin of the immaculate panel that hangs at the Frick. While much of the portrait is shadowy and smudged, Cromwell’s face, with its shifty eyes, is almost eerily clear. A scarcely readable Latin scroll, added to the painting after his beheading, praises the sitter as “a good and prudent man. An unwavering minister, a man of courageous heart,” one “both pious and loyal to his country.”

After its moment in the public eye, the portrait returned to Tyttenhanger, there to remain for the next half century.

A photograph of Thomas Cromwell from the exhibition catalog of the National Portrait Exhibition of 1866 in London (Getty Research Institute/Hatha Trust)

Like many collectors, Henry Clay Frick had a wish list. Holbein was near the top. In the early 20th century, the artist’s reputation was in the ascendant. Writing to the noted philanthropist and patron of the arts Isabella Stewart Gardner in 1899, the art historian Bernard Berenson decreed that “no master, scarcely Raphael excepted, is harder to get, more in demand, and fetches relatively higher prices than Holbein.”

Frick had come tantalizing close to acquiring Holbein’s full-length portrait of Christina of Denmark in 1909, losing out after a famous, last-minute campaign kept the painting at Britain’s National Gallery. It was a bitter loss for Frick, and one that, according to the author Cynthia Saltzman, “shook his confidence in Charles Carstairs,” the American director of the London branch of the art gallery M. Knoedler & Co., which acted in partnership with another firm on that sale.

Just three years later, in January 1912, Carstairs redeemed himself with the delivery of another celebrated Holbein trophy—the Sir Thomas More—to Frick. And then yet another work by this artist came into view. In January 1914, a young Lord Caledon, just 28 years old, sold Holbein’s Thomas Cromwell to the London art dealers Thomas Agnew & Sons for £30,000, then a substantial sum. After centuries of seclusion, the portrait was out in the world.

By the time Frick first saw the painting, on a May 1914 visit to London, Carstairs had brokered its sale to Hugh Lane, the Irish art collector and founder of the Dublin Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, for £38,000. The dealer kept in touch with Frick, however, perhaps suspecting that Lane, whose financial problems had become the stuff of legend, might offer the painting for sale.

On May 26, 1914, Carstairs sent Frick a progress report on the portrait, then in the process of being restored:

DeWild [sic] has been working on the Holbein ever since you left. It is coming out very beautifully. The table cloth is a beautiful emerald green, which places the man well behind the table, and that, together with the blue background, makes a wonderfully brilliant effect. The scroll at the top came away completely, and de Wild was able to preserve the beautifully blue background underneath …

The work was likely done by Carel de Wild, a Dutch restorer and art dealer who often advised Frick. Lane was so pleased with his restoration that he considered asking £80,000 for it—nearly 40 percent more than its estimated value just months earlier. “I simply put these facts before you,” Carstairs wrote to Frick, “which you can act upon, or not, as you think fit.”

This consummate dealmaker didn’t enjoy being played. His cabled response was terse: “Thanks not in market at present. Frick.” Seeing a deal slip from his grasp, Carstairs wrote back the next day, this time requesting £60,000 in cash by “tomorrow morning,” plus a 10 percent commission to his gallery.

Frick’s answer, if there was one, isn’t recorded.

Nearly a year later, on April 2, 1915, Frick received a letter from a New York artist and art dealer named Alice B. Creelman that told an extraordinary tale. “I came in touch with a small collection of wonderful paintings,” she began,

belonging to a titled man who has been ruined by the war and must part with them or go bankrupt. They are superb … unquestioned in pedigree and authenticity.

There is a beautiful Titian, really beautiful and not only historic, and a superb Holbein (I think the finest in the world).

Seeing these artists’ names in the same paragraph would have instantly told Frick who the seller had to be—both Titian’s Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap (c. 1510) and Holbein’s Thomas Cromwell belonged to Lane. It’s easy to imagine his excitement. He must have known that these prized works of art were his to win.

Creelman, like Lane, was strapped for cash. Her husband, the journalist James Creelman, had died two months earlier on a reporting trip to Berlin, just hours after filing an exclusive interview with German chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg. Left alone with three small children, Creelman was in stark circumstances. “With the passing away of my husband, my life and fortune have been completely wrecked,” she wrote. Frick must have reached for the phone then and there, inviting her to visit him that day.

It would have been a short stroll from Creelman’s home on the Upper West Side to Frick’s mansion on Fifth Avenue—a mile or so across Central Park, then awakening into spring. The occasion must have felt momentous: so much was riding on these sales. She wrote to Frick that very afternoon, just after returning home. To gush. “I have spent much of my life studying in the great galleries, private and public, of Europe, and I have never seen a choicer group than this,” she wrote, adding that she had been

enchanted with the beauty of your paintings in their surroundings. They never looked so beautiful as against that green velvet wall and in the perfectly proportioned and lighted gallery. The whole house is a delight. It is in the most exquisite taste, as dignified and real [emphasis hers] and so full of beauty.

The correspondence between Creelman and Frick is a study in contrasts. Her missives are written on small notecards in a flowery handwriting that can wander—climbing margins, doubling back—all over the paper’s surface. Frick’s letters, typed by secretaries, are a series of clipped rectangles. They’re pure business, without an extraneous sentiment or word.

The pair moved quickly towards an agreement. Citing Lane’s “quixotic and capricious temperament” and legendary frugality (“he frequently dined on a bun and a piece of fruit,” one acquaintance sniped), Creelman asked Frick to ensure that the transaction passed entirely through her hands. Frick replied with an offer to buy both paintings for £60,000 (more than $6 million today). In a letter to Creelman four days later, he made the sale of the Holbein contingent on his inspecting it to confirm that it was the work he’d seen in London, the one de Wild had so expertly restored the year before. Lane agreed, but for some reason, arranged separate passage for himself and his paintings.

Lane was uncharacteristically subdued before his departure, according to his biographer, the Irish journalist Robert O’Byrne. He confessed to being terrified at the prospect of crossing the Atlantic in the midst of World War I, when German U-boats plied its waters. “He seemed to have prevision of the danger that he was running,” a friend recalled. Even so, he boarded an ocean liner in Liverpool on April 11, arriving in New York nine days later. In bustling Manhattan, far from the gloom of wartime Britain, the Irishman’s morale improved. A few days after his arrival, he, too, stopped in to see Frick and his treasures.

Strangely, Lane never actually saw Thomas Cromwell in New York, although he’d traveled across the ocean, in part, to do so. By the time the painting arrived in America, he’d hurried off, citing a business meeting he had to attend in Dublin. On his last evening in Manhattan, he stopped into One East 70th Street to bid farewell to Frick. The next day, May 1, he boarded a vessel that its owner, the Cunard Line, advertised as “the biggest, fastest, safest, and most luxurious liner in the world.”

By then Holbein’s Thomas Cromwell was also in transit, having departed from Liverpool on the S.S. Philadelphia the week before. Lane and his Holbein may well have passed each other—literally, ships in the night—as they crossed the Atlantic, each one moving in the opposite direction. Traveling at just over 23 knots, Lane’s luxury liner would have been halfway across the ocean on May 4, the day the Philadelphia passed the Statue of Liberty, entering New York Harbor. The portrait’s arrival on American shores was heralded in articles in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times.

Three days later, on May 7, 1915, Lane’s boat—the Lusitania—was 11 miles off the Irish coast when it was torpedoed by the German submarine U-20. According to a friend who survived, Lane darted back into the vessel from the deck to help another friend escape. “This is the end of us all,” he said as he went. The boat took just 18 minutes to sink. About 1,200 of its passengers and crew, Lane among them, drowned. There were fewer than 800 survivors.

Ten days later, having inspected the Holbein, Frick wrote a check for £60,000 to the Estate of Hugh Lane for the two paintings, an amount that included the cost of shipping and other charges. The next day, he dispatched a $26,664 check to Creelman for her commission on the sales. When she wrote to Frick on May 11 to thank him for the payment, Lane’s apparent fate was very much on her mind. “No word has been received of poor Sir Hugh,” she wrote. “It looks hopeless.”

There’s no record of a reply.

And so, after centuries spent in timeworn English stately homes, Holbein’s Thomas Cromwell landed at a shiny, New World equivalent. Shortly after it arrived, Frick juxtaposed it with the portrait of More, placing each painting on either side of the Living Hall’s mantelpiece. Perhaps he enjoyed the silent enmity that seemed to emanate from their frames.

After Frick died in 1919, his widow, Adelaide Childs Frick, continued to live in their Fifth Avenue residence. With her death in 1931, the mansion became the property of the public. Frick’s will stipulated that his residence, furnishings, art, and decorative objects should be bequeathed to the city of New York “for the purpose of establishing and maintaining a gallery of art … and encouraging and developing the study of the fine arts.” An extensive renovation ensued, transforming a private space into a public one, and in December 1935, the Frick Collection opened its doors.

“He was certainly one of the most fabulous capitalists produced in America,” The New York Times trilled, just before that highly anticipated opening. Today, our view of Frick is rather more complex. Indeed, certain words—ruthless, robber baron, union buster, and the like—cling to his name like metal shavings around a magnet.

Sir Thomas More, Hans Holbein the Younger, 1527 (Wikimedia Commons)

After the Frick closed for renovation in 2020, many of its holdings were moved four blocks uptown to the former site of the Whitney Museum, the brutalist masterpiece by architect Marcel Breuer, which was temporarily dubbed Frick Madison. There Cromwell and More’s face-off continued. A short time later Thomas Cromwell, like an aging rock star in a broken-up band, headed to the West Coast on a tour of its own. By October 2021, the portrait was taking the spotlight in Holbein: Capturing Character in the Renaissance, an exhibition at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, organized by that institution and New York’s Morgan Library & Museum.

It was a rare occasion. The Frick has a longstanding tradition of not lending works acquired by its founder to other institutions. It was also the first time in decades that the two portraits had spent time apart. After the Getty exhibit closed in January 2022, Thomas Cromwell winged its way back to New York, where it again assumed its position on Frick Madison’s fourth floor. By then Sir Thomas More was on its way out the door. That portrait, earlier deemed too fragile to travel out west, was transported two miles south on Madison Avenue instead. There it joined the exhibition Holbein: Capturing Character, on view at the Morgan until May 15.

Art isn’t static; the best of it changes along with us. Examining Thomas Cromwell in the absence of its more celebrated neighbor allows us to see it in a new light, and not just the kind that pours through Frick Madison’s outsized, asymmetric windows. Mantel’s hugely popular literary reincarnation of Cromwell deepened our view of him; the peripatetic wanderings of Holbein’s Thomas Cromwell, its alighting and returning again, continued the process. We see more in his portrait now—as I, for one, can attest.

At some point in 2023, when the Frick renovation is complete, the two Holbeins will resume their places on either side of the great fireplace, just as Henry Clay Frick first positioned them. Once they’re on the wall again, they’ll go back to staring each other down.

Or so we like to think.