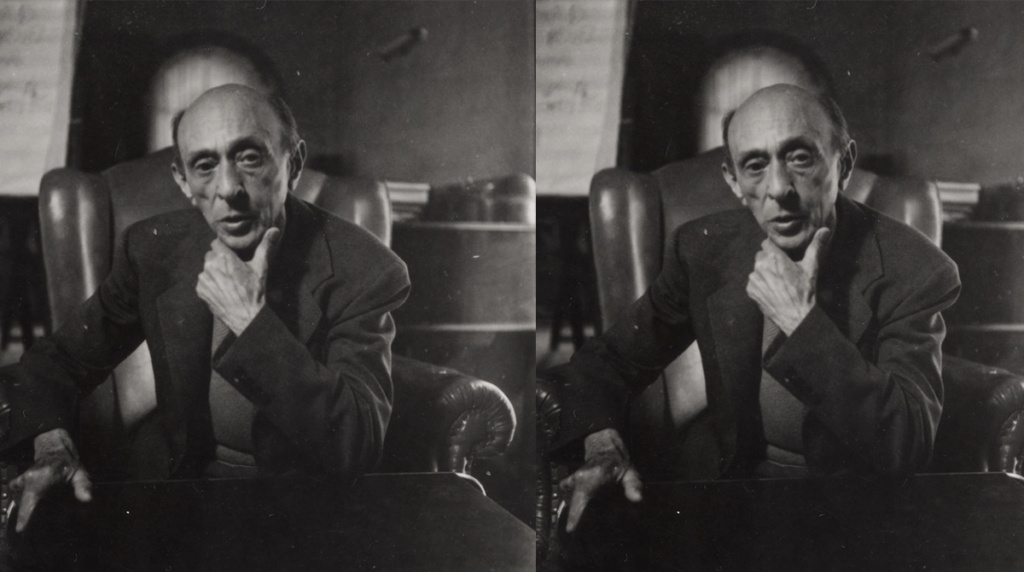

Among the pop culture stars of the mid-20th century, few were as diversely talented as the inimitable Oscar Levant. Urbane and self-lacerating, Levant cultivated a witty persona shaped heavily by his own neuroses and mental instabilities. The master of the cutting one-liner, he starred in films, wrote books, hosted his own television show, and appeared as a guest on the Jack Benny Program and The Jack Paar Tonight Show. He was also a popular pianist, more popular, even, than Vladimir Horowitz for a time, and as a recently released box set makes clear, he was an artist of considerable talent. In that collection of recordings, you will hear the repertoire for which Levant was best known—Gershwin’s Piano Concerto and Rhapsody in Blue—as well as works by Beethoven and Brahms, Chopin and Debussy, Liszt and Ravel, Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff. Levant’s interpretation of the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1, for example, with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy, is an idiosyncratic marvel, at once virtuosic and highly musical. More than three decades ago, I bootlegged that recording off the radio, later taking the cassette with me to college and playing it often for musician friends of mine. “You’re never going to guess who the pianist is,” I’d always say.

Levant’s most famous musical association was with Gershwin, but an even more interesting relationship, I think, was his friendship with Arnold Schoenberg. In 1934, Schoenberg arrived in California from the East Coast, having emigrated from Germany the year before, just as Hitler had ascended to power. Schoenberg found work teaching at UCLA and USC, and he was able to buy a house not far from the UCLA campus (Shirley Temple lived across the street). He took to his new environs at once, entertaining Hollywood stars on Sunday afternoons and playing a weekly game of tennis with Gershwin. In a letter to his dear friend and former student Anton Webern, Schoenberg wrote of California: “It is Switzerland, the Riviera, the Vienna woods, the desert, the Salzkammergut, Spain, Italy—everything in one place. And along with that scarcely a day, apparently even in winter, without sun.”

Musically, however, Schoenberg found the audiences of the West Coast to be far less interested in his brand of modernism than their East Coast counterparts had been. His attempts to conduct his own compositions, moreover, had been unsuccessful, partly due to his own technical limitations on the podium. But if the public displayed ambivalence or antipathy to this towering figure of Viennese modernism, musicians flocked to him, eager to delve with him into the depths of counterpoint, harmony, and composition. The conductor Otto Klemperer (the esteemed music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic) was one of these pupils. Another was Levant, who studied with Schoenberg intermittently during a span of three years, calling him “the greatest teacher in the world.”

In 1942, when Levant was back in New York City, he commissioned Schoenberg to write a piano piece for him. Expecting something short, perhaps the length of a Chopin Nocturne, Levant “wasn’t prepared,” as he later wrote, for the full-length concerto upon which the composer instead embarked. Accompanying a letter dated August 8, 1942, Schoenberg sent roughly a quarter of the manuscript to Levant. The work, Schoenberg wrote, would be in four parts and would include a scherzo, an adagio, and a rondo-like finale. But though Levant had already paid an installment of $200, a final fee for the commission had yet to be agreed upon. Schoenberg naturally wanted to finalize the details. What followed was a delicate back and forth, the two artists acting like a pair of uneasy dance partners. There was flattery of Levant’s technique, and a promise that the pianist would have exclusive performing rights for an entire season, but when Levant finally realized that Schoenberg wanted a fee of $1,500, the equivalent of more than $23,000 today, he wrote that such a figure was

out of [the] question. Possibility of performance this year due to conditions and my own problems is negative. Am delighted with wonderful quality of concerto however I will have to withdraw my present capacity as patron and leave the concerto to your complete possession and discretion. I could not pay the fee nor would the concerto gain by my exclusivity.

Not yet abandoning hope, Schoenberg continued to cajole and prod, but after further discussion, Levant sent another telegram, bringing the negotiations to an end:

Dear Mr. Schoenberg I hereby withdraw utterly and irrevocably from any further negotiations concerning your concerto. I wish no longer to be involved in its future disposition. Letter following with check for one hundred dollars.

Regards

Oscar Levant.

In the end, a lawyer named Henry Clay Shriver, another former pupil of Schoenberg’s and more recently a teaching assistant of his, paid the composer $1,000. And so, it was to Shriver whom Schoenberg dedicated his Piano Concerto op. 42.

Not until February 6, 1944—76 years ago today—did the premiere of the work take place, with Eduard Steuermann as the piano soloist and Leopold Stokowski conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra. (Both musicians were sympathetic to Schoenberg’s 12-tone idiom—Steuermann, another musician in exile, had studied with the composer and performed many of his premieres, dating back to 1913.) The concert was broadcast to a national audience, and though Schoenberg himself was thrilled, the critical reception was, at best, mixed. Whereas Olin Downes dismissed the work in a hostile review in The New York Times, Virgil Thomson was far more generous. The concerto, Thomson wrote,

is poetical and reflective. And it builds up its moments of emphasis by rhythmic device and contrapuntal complication, very much as old Sebastian Bach was wont to do. Its inspiration and its communication are lyrical, intimate, thoughtful, sweet, and sometimes witty, like good private talk. …

Its particular combination of lyric freedom and figurational fancy with the strictest tonal logic places it high among the works of this greatest among the living Viennese masters (resident now in Hollywood) and high among the musical achievements of our century. With the increasing conservatism of contemporary composers about matters harmonic, many of our young people have never really heard much modern music. Radical and thoroughgoing modern music, I mean. It is too seldom performed. Well, here is a piece of it and a very fine one, a beautiful and original work that is really thought through and that doesn’t sound like anything else.

To those resistant to 12-tone music, the concerto was just another baffling modern score. Yet it was also attacked by those on the musical left, the aficionados of the avant-garde, who ordinarily would have genuflected before Schoenberg. To them, the piece was not modern enough. Indeed, Schoenberg had taken certain liberties with this 12-tone work in the interest, it would seem, of accessibility. There are several nods to old-fashioned triadic harmony, and there’s a prominent doubling of octaves—generally a no-no in 12-tone music. The piano part even features two cadenzas, an aspect of concerto writing from an earlier age. And what about the final chord of the piece, which astonishingly ends things in the key of C major? What was Schoenberg up to? It certainly seems that under the wilting California sun, the autocratic, unyielding, Olympian composer had become more flexible, relaxing some of the dicta that he had codified in the early 1920s—and that his followers adhered to with messianic zeal.

The piece is more accessible than, say, the Violin Concerto that Schoenberg wrote in 1936, but why should it be denigrated for that? Why shouldn’t certain rules be broken as long as the spirit of the law remains intact? More important than the mathematical rigor of the tone row and its many permutations is whether a piece of music moves us, makes us think, quickens our pulse, or puts us in a funk—whether it imbues us with deep feelings and makes us want to hear it again. So it is for me with Berg’s Violin Concerto, Webern’s two late Cantatas, and Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra, among other 12-tone masterpieces. And so it is with Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto.

It helps to know the program behind this deeply autobiographical piece, which charts the composer’s experience of emigration and exile. Although he did not include them in the published score, Schoenberg had earlier provided descriptive titles for the concerto’s four parts. “Life was so easy”—this was the phrase that had characterized the opening section. Is it any wonder, then, that the music conjures up a Vienna of an earlier, less turbulent time, the age of the Habsburgs, perhaps, for there in the opening measures is a melody, played by the unaccompanied piano, that takes the form of a waltz. It’s a waltz that’s wistful, cool, even detached—the nostalgia here is dry, not wet—and when the orchestra enters after those opening eight measures, it acts a bit like a Greek chorus, commenting in spurts on the eloquent piano line. Later, the distance between soloist and orchestra will narrow and the two forces will become a synthetic, symphonic whole.

As the music gains in intensity, we hear disparate, fragmented outbursts from the orchestra that sound like angry voices in a growing crowd. The music accelerates, the piano striking a series of accented notes above the plucked pizzicato of the strings, and everything hurtles toward the concerto’s second section, which begins with a frightening passage in the trombones. “Suddenly hatred broke out” was the title that described this volatile, frenetic scherzo, which evokes Germany under the Third Reich. Schoenberg’s effects include cascading passages in the xylophone, cries of desperation from the piccolo, the agitated flutter tongue from the winds and brass. After a brief, welcome respite, the music plunges on in great, bleak torrents.

A lengthy orchestral introduction opens the moving Adagio, which is worthy of its erstwhile title, “A grave situation was created.” This highly expressive section is both turbulent and mournful, and if earlier passages in the concerto feel like chamber music, the textures here are thick and dense—a full-blown orchestral lament, the sense of foreboding aided by the eerie repetition of certain notes and phrases. A poetic cadenza leads to the rondo finale, a section marked giocoso (meaning “playful”). Considering what we’ve just heard, Schoenberg must have intended something ironic here. Even the section’s original title, “But life goes on,” seems woefully inadequate, given what was happening in Austria and Germany at the time of composition. But then, what we’re glimpsing here is not, I think, a portrait of Europe during the war, but rather a depiction of Schoenberg himself, of the artist in exile, the old world musician remaking himself in a sunny new world. A palpable darkness lies beneath the impish humor, all that darting to and fro, so that at times we seem to be caught up in some whirling, maniacal dance. Here we can sense Schoenberg’s alienation, the confusion felt by a man who embraced his Southern California life, who adored The Lone Ranger and UCLA football games, but who, having embarked on his exile at the age of 60, never really took off his European garb and was ultimately unwilling to assimilate.

Over the years, the concerto has had many champions, including Alfred Brendel, Glenn Gould, Maurizio Pollini, and Mitsuko Uchida. The tantalizing question is: What would Oscar Levant, with all his quirks and musical intelligence, have made of this piece? In an essay on the Schoenberg Piano Concerto, Brendel asserts that “Levant had no use” for it: “One could scarcely imagine him playing this particular work anyway.” That assessment seriously undervalues Levant’s abilities as a pianist (of which Schoenberg had zero doubt) as well as his interest in modern music. Listen to Levant’s own Piano Concerto, also composed in 1942, and you’ll hear echoes of Schoenberg, of Prokofiev, of Darius Milhaud. If only that Levant box set contained a reading of Schoenberg’s concerto. It would have been, without doubt, one of the most compelling documents in music history.

Listen to Glenn Gould play Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto, with Dimitri Mitropoulos leading the New York Philharmonic: