The Ultimate Pawn Sacrifice

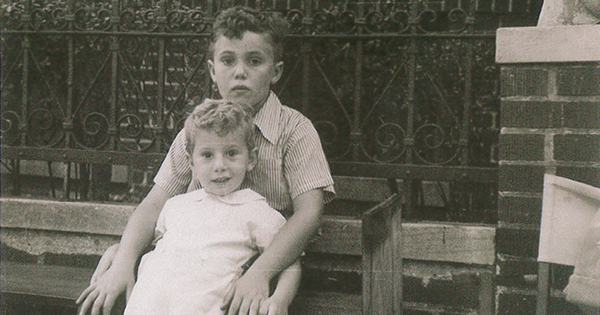

My brother’s life mirrored that of Bobby Fischer, the deeply troubled chess master

In the fall of 1957, soon after my younger brother Robert entered Brooklyn’s Erasmus Hall High School, he joined the chess club. Bobby Fischer entered Erasmus that year, and he too joined the chess club. By then, Fischer was United States Junior Chess Champion, yet whenever Robert tried to get Fischer to play with him, Fischer refused, saying, “With you, Neugeboren, I don’t play.”

“Why not?” I’d asked my brother at the time.

“Because,” Robert said, “he said I played crazy.”

Watching Pawn Sacrifice, the 2014 movie about Fischer’s 1972 victory over Boris Spassky for the World Championship, I kept thinking about how young and gifted my brother and Fischer were once upon a time, and of the wonder, waste, and sad trajectories of their strangely parallel lives.

I gave Robert his first chess set. Bobby Fischer’s sister, Joan—like me, five years older than her brother—gave Bobby his first chess set. Fischer’s mother, Regina, was a registered nurse. So was our mother. Having divorced Fischer’s father when Bobby was two years old, Regina raised her two children as a single parent. Our parents never divorced, though they constantly threatened to do so, but because our father—blind in one eye and legally blind in the other—failed at every business he tried, it was our mother, often working double hospital shifts, who supported our family.

Robert recalled coming home from school one afternoon to find our mother standing in the middle of the living room, hammer in hand.

“Am I the only man around here?” she asked.

In 1957, two months before his 15th birthday, Fischer became the youngest-ever United States Chess Champion. He had little interest in school, and shortly after his 16th birthday, he dropped out of Erasmus. A few months later, he moved out of his mother’s apartment.

Robert was famous in our neighborhood for singing and dancing on street corners, and starring in musical productions. At 13, he won a citywide essay contest, and at 16, a New York State Regents College Scholarship. But school bored him, so that same year, he dropped out and moved out of our parents’ apartment.

“We all started out together at Erasmus,” Robert often said. “Bobby Fischer, Bobbi Streisand, and Bobby Neugeboren. But then the three Bobbys dropped out.” (When I told Robert that my research indicated that Barbra Streisand had not dropped out but had graduated with a 93 average, he told me I didn’t know what I was talking about.)

When, in 1962, Fischer’s mother and sister moved out of their apartment, Fischer moved back in. That same year, following a drug-enhanced cross-country trip, Robert moved back into our parents’ apartment, became floridly psychotic, tried to strangle our father, and made sexual advances on our mother. He was straitjacketed and taken to a local emergency psych ward. He was 19 years old and would, from that point on, spend most of his life in mental hospitals, psych wards, and halfway houses. He died in 2015 in a nursing home in the Bronx, at age 72.

Both mothers were active in antiwar organizations, and at a peace march in 1960, Fischer’s mother met Cyril Pustan, a college English teacher she later married. They settled in England, and in the last four decades of her life, she saw Bobby rarely.

In 1973, when my brother was locked up in a New York state mental hospital, our mother and father moved to Florida. Our father died three years later without seeing Robert again. During the remaining 30 years of our mother’s life, she saw Robert twice.

Pawn Sacrifice opens with Fischer holed up in a small hotel room, his eyes darting here and there, the soundtrack and hand-held camera providing booming noises and shadowy figures that dramatize his delusions. (In actuality, during the 1972 championship match, Fischer stayed in a brand-new villa outside Reykjavik and also in a three-room presidential suite in Reykjavik’s Hotel Loftleidir.) What I found troubling while I watched Pawn Sacrifice was not the unsurprising liberties the film takes, but the way it reduces the complexity of Fischer’s character to a simplistic portrait: Fischer as a “mad genius,” more mad than genius. For most of the film, Fischer broods silently, is bombastically paranoid, accusing Russians—and Jews!—of plotting to screw him, and expresses himself almost solely in tantrums and tirades.

In the film, after we’re told that whoever wins the next game will become World Champion, Fischer makes an opening move he has never before used in competition (the Queen’s Gambit Declined), a move that, by its unpredictable nature, puts Spassky off his game. Fischer was known for his limited repertoire, well-rehearsed systems, and predictable openings and variations on those openings. Suddenly, though, he was “playing crazy”—he was playing in the erratic way Robert played, and in a manner Spassky, who had studied Fischer’s habits, had not anticipated. Fischer wins the game and goes on to win the match.

After defeating Spassky—except for a 1992 rematch in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, which resulted in his permanent exile from the United States (for violating a travel ban)—Fischer never in the remaining 35 years of his life played tournament chess again. I wondered: despite his legendary self-confidence, did he fear losing more than he loved winning, and if so, did this, perhaps, explain his refusal six decades earlier to play against Robert?

During the years following his victory over Spassky, Fischer’s primary adversary, according to rambling broadcasts he made from the Philippines, became the international Jewish conspiracy. Jews were a “filthy, lying bastard people,” he said, the Holocaust “a money-making invention.” At one point, convinced that secret agents were sending signals through his jaw, Fischer had all his dental fillings removed.

During these same years, Robert became obsessed with Jewish dietary laws, demanding that each residence he lived in provide him with kosher food, yet he sometimes disavowed his Jewish identity, claiming to have been born a Baptist, to have converted to Christian Science, and to have evolved into a Buddhist. By the time he was in his 30s, his teeth had rotted or been knocked out or pulled, and he wore dentures. When the staff at a state mental hospital punished him by taking away his dentures and subsequently lost them, Robert refused to be fitted with new ones. He remained toothless for the rest of his life.

In 2004, Japanese authorities imprisoned Fischer for attempting to leave Japan without a valid U.S. passport, and Fischer wrote to the government of Iceland requesting citizenship, which it granted. He lived in Iceland until January 17, 2008, when, following a long illness brought on by a urinary tract infection for which he refused surgery or medications, he died of renal failure.

“I don’t believe it’s true,” Robert said when I told him the news.

“But it was in The New York Times this morning,” I said.

“The New York Times? ” Robert scoffed. “All the news that’s fit to spit, if you ask me.”

A few weeks later, Robert informed me that Fischer had moved into his halfway house and was living in the room above his. He began talking about walking home from school with Fischer, about visiting Fischer in his apartment, and about a satchel containing a chess set that Fischer always carried with him.

Robert’s reaction to Fischer’s death put into relief yet again the sorrowful arc of his own life: his early brilliance, flair, and sweetness had devolved into an ongoing misery whose pain I could only imagine. And yet, I believed, the mad thoughts and actions that marked his life had served—perhaps as they had with Fischer—to defend against feelings and thoughts more terrifying than the symptoms of madness he’d exhibited. And wasn’t madness itself a kind of exile wherein my brother, like Fischer, was disconnected from everything—friends, relatives, places, work, and passions—that had once held meaning and pleasure for him?

When, during the past half-century, people asked me what Robert’s diagnosis was, if I replied with a clinical term—schizophrenia, manic depression—they usually nodded knowingly. In more recent years, I replied with questions of my own: If I tell you my brother is schizophrenic, what will you know about his condition or his life—about who he is? Although Robert had an unenviable life, he remained as fascinating, complex, and unique in his feelings, thoughts, and history as any of us. To perceive him as “a schizophrenic” is to dismiss everything that made him Robert, including his sense of the life he did not have.

Fischer was often enraged, paranoid, and delusional. But he was more than that, especially in the years before he defeated Spassky. Four years before that match, Fischer happily participated in a tournament in Israel. When World Champion Mikhail Tal was hospitalized during a tournament in Curaçao, Fischer was the only player to visit him. Fischer prepared for his match against Spassky at Grossinger’s, a Jewish resort in the Catskills, where he played tennis and swam—at the time a novel training method for chess players. Later he vacationed in Bermuda as the guest of journalist David Frost, lounging by the pool and talking with economist John Kenneth Galbraith. In Reykjavik, he befriended his Icelandic security guard, had dinner at the guard’s home, played with the man’s children, and volunteered to babysit them. Fischer loved tailored suits and comic books, wrote books, had girlfriends, and left thousands of dollars under his pillow for the hotel maids who cleaned his room.

How easy it is, once we reduce someone to a label (“lunatic,” “schizo”), not to think beyond familiar stereotypes of “mad geniuses” or “crazies.” How simple it becomes to exile them to nonhuman categories, and thereby cut ourselves off from them, and from any understanding of the complexity and mystery of who they are.

On one of my last visits, Robert talked about all the money he was expecting—from Social Security, various bank accounts, and his monthly disability allowance.

“I have all this income,” he said. “But do you know what my problem is?”

“No,” I said. “What’s your problem?”

“No outcome.”