Mr. Straight Arrow: The Career of John Hersey, Author of Hiroshima by Jeremy Treglown; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 384 pp., $28

This admirable book about an admirable man, while insisting it is not a biography, recounts enough of John Hersey’s life to explain some of his enduring concerns and the arc of his career. It belongs to that elegant, reticent, wholly non-sleazy, and sadly disappearing genre known as literary biography, and for anyone interested in how a writer’s life is really lived as opposed to its incidental moments of glamour, Jeremy Treglown’s account of Hersey’s career—its constraints and opportunities, the worries and satisfactions, and the nature of the actual work—is deeply satisfying.

Hersey’s parents were missionaries working on behalf of the YMCA in China, where the boy lived until the age of 10, speaking Chinese before he spoke English. He admired his parents as ethical models but couldn’t accept their religious belief and sought, Treglown writes, “a purely rational support system for the humanitarianism that, in the elder Herseys, was nourished by Christianity.” His Chinese childhood also gave him, Hersey always believed, an outsider’s view of the American century.

After a high-WASP education at eastern private schools and Yale, where he belonged to that nexus of insiderdom, Skull and Bones, Hersey went to work at Time and Life. The war was on, and at first Hersey worked in New York as an editor, shaping war correspondents’ dispatches into magazine copy. He used those dispatches to write his first book, Men on Bataan, a work done with urgency and purpose but little of the direct reporting that Hersey would later be famous for. Bataan fell to the Japanese after a four-month battle on April 9, 1942. With a speed now inconceivable, the book came out in early June. General MacArthur was its hero, in charge of a valiant if futile defense of the Philippines.

Hersey then became a war correspondent himself, joining a platoon of Marines on Guadalcanal in October 1942 for what turned out to be a calamitous encounter. He recorded what he saw in a 20,000-word account published by Knopf as a book four months after the episode. Again he had to write about defeat in a way that was truthful but did not undercut the war effort, and, in skillfully doing so, he gained tremendous personal prominence.

John F. Kennedy wrote to his sister Kathleen, “I see [Hersey’s] new book ‘Into the Valley’ is doing well. He’s sitting on top of the hill at this point—a best seller—my girl, two kids—big man on Time—while I’m the one that’s down in the God damned valley.” His girl, because Hersey had married Frances Ann Cannon, heiress to the Cannon towel fortune, who had been Kennedy’s girlfriend before the war. They would have four children before they were divorced in 1958, when he married Barbara Day Addams Kaufman.

Half a year after writing to his sister that he was “in the God damned valley,” Kennedy commanded a patrol torpedo boat in the Pacific that was sunk by a Japanese destroyer. Hersey wrote about the incident in The New Yorker, focusing on the heroism of young officer Kennedy in saving his men rather than on the stupidity of their mission. In doing so, he established JFK as a war hero and, without meaning to, became part of the Kennedy political juggernaut.

Like many nonfiction writers before and since, Hersey wanted to write fiction, but unlike most nonfiction writers, he was successful at it. After reporting on the war in the Pacific for Time, he participated in the Allied landings in Sicily embedded with General Patton’s forces. A Bell for Adano, his first novel, uses his knowledge of the military occupation of Sicily to tell the story of townspeople reeling from the war, needing the spiritual sustenance represented by a new church bell as much as they needed food. The protagonist, Major Joppolo, who understands the locals, differs from most of the American soldiers and officials who ignore their customs and treat them callously. Hersey understood that people focused on winning a war were likely not to be prepared to govern, and the book was a groundbreaking work about American behavior in occupied countries. A Bell for Adano was immensely popular, a best seller, and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, made into a Broadway play with Frederic March starring as Major Joppolo and then into a film with Gene Tierney playing a fisherman’s daughter.

Hersey was already celebrated when he left Time and Life in 1945 and began writing primarily for The New Yorker, freer than he was under Henry Luce’s patronage to question the homespun optimism that Luce promoted. From then on, underlying almost all of Hersey’s work was a critique of the American way of dominating the world.

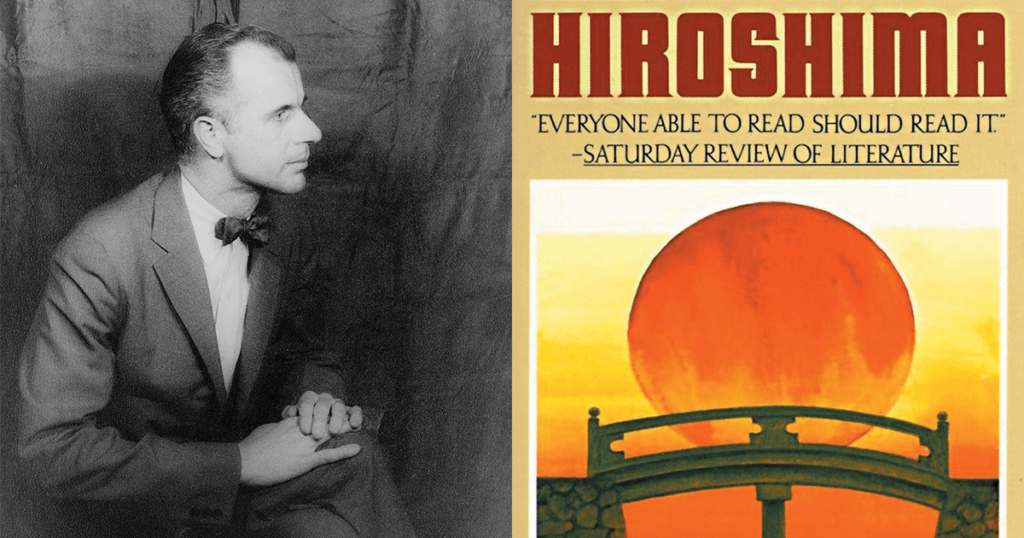

Hersey is now remembered principally for Hiroshima, his magisterial account of the dropping of the atomic bomb from the point of view of Japanese who survived the attack. The power of his reporting and of his prose brought home to millions of people all over the planet the horror of nuclear warfare and first raised questions about whether such destruction is justifiable. The New Yorker, which ran the entire piece in August 1946, a year after the bombings, allowed almost nothing else to run in the issue, underlining its moral authority. Hersey was only 32 years old.

Four years later, when he published The Wall, a novel about the uprising in and the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto, based on accounts found in the rubble by people who had died there, it was treated with all the respect due to its subject and its author, already known for his high moral stances. But one young Jewish writer, Leslie Fiedler, judged it as a work of literature rather than an expression of right thinking, and found it wanting. His critical review for Commentary, the magazine of New York Jewish intellectuals, was rejected and a more enthusiastic reviewer found. But Treglown tracked down Fiedler’s unpublished response to the rejection, cast as a dialogue between the Critic (Fiedler), whose concerns are with art, and the Kibbitzer (Commentary’s editor, Irving Kristol, made to stand for conventional values). Every moment the Kibbitzer cites as deeply moving, the Critic rejects as a platitude, and he accuses Hersey of tidying up his Polish Jews: in his effort to tap into feelings of common humanity, he glosses over their differences from Connecticut Yankees. Time has come around to Fiedler’s view, and although The Wall has been translated and reprinted, it is, writes Treglown, “best known today for cultural-historical reasons, as the first example of what has become a crowded genre.” As he does in finding this unpublished piece in the Commentary archives, Treglown produces little miracles of research without tooting his own horn.

Hersey went on to write several other novels, including A Single Pebble, The War Lover, The Child Buyer, and The Call, and although they all did well, he never had the kind of success with them he had had with Hiroshima. He did massive research for all of his books, and Treglown suspects that the research worked to stifle Hersey’s imagination. The fact is, some writers are novelists and some are not, and it’s not always the novelists who have the greatest impact, although they tend to enjoy the most popular prestige. The career of John Hersey certainly shows that.

Everything Hersey did oozed the moral authority alluded to in the unfortunate title of this book, Mr. Straight Arrow. The phrase came from a New Yorker staffer who was comparing the two husbands of Barbara Hersey, the first being Charles Addams, the cartoonist who created Morticia, and the second, our Mr. Upright. In American usage, the term “straight arrow” almost always carries pejorative weight, and, in his later years, Hersey’s reputation for solid citizenry weighed him down like a heavy cloak. Ironically, this is one biography in which a hint of something at least semi-sleazy might have helped, restoring Hersey to the realms of the morally imperfect, that is to say, the human. Treglown, who admires him, should have saved Hersey from the negative connotations of “straight arrow.” But it is about the only wrong step he takes. His is a worthy start to what hopefully will be a renaissance of interest in John Hersey.