This Man Should Not Be Executed

Billy Joe Wardlow murdered a man, but mitigating facts say he should not pay for that crime with his life

When he was 18, in 1993, Billy Joe Wardlow shot and killed an 82-year-old man named Carl Cole during a robbery in Cason, Texas, a rundown town of fewer than 200 people in the state’s rural northeast corner. Two years later, he was convicted of capital murder, making him eligible for the death penalty. The jurors who convicted him, in deciding whether to sentence him to death or to life without parole, had to determine first whether he “would constitute a continuing threat to society,” including inside the prison. When the answer to that question was yes, they had to decide whether, “taking into consideration all of the evidence, including the circumstances of the offense, the Defendant’s character and background, and the personal moral culpability of the Defendant,” there was still enough mitigating evidence to warrant a life sentence without parole. The jury said no, and sentenced him to death.

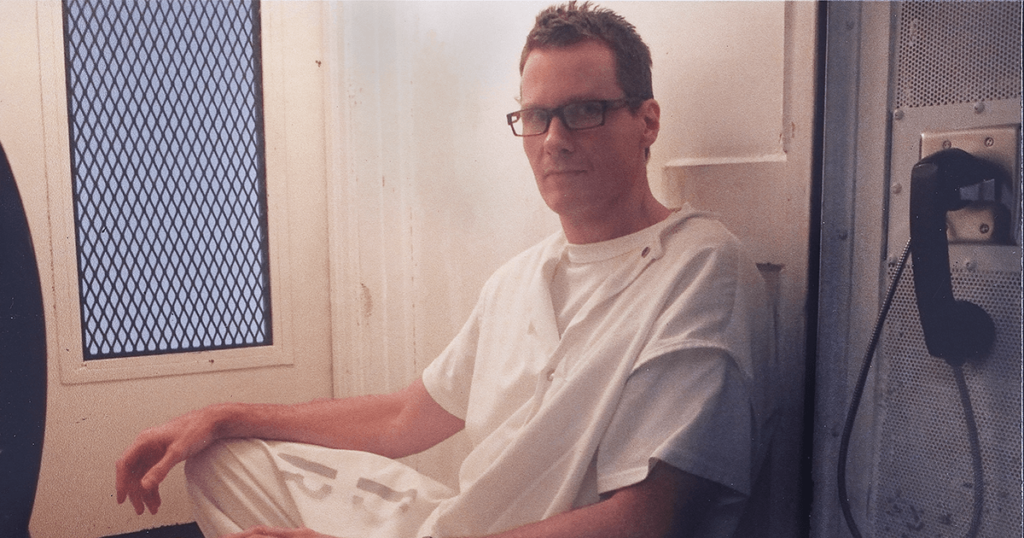

Last June, I interviewed Wardlow at a maximum-security prison called the Polunsky Unit, located 80 miles northeast of Houston, where he is waiting for his execution on death row. He has been incarcerated for a quarter of a century, but the state has now set a date for his death: April 29, 2020. His lawyers, Richard Burr and Mandy Welch, having gotten to know him well in the 23 years that they have represented him, told me they are convinced that time has shown the jury to have been wrong in determining Wardlow posed a future danger. The more I have read about his case and his life, the more I think they are right. Wardlow stands out as someone the legal system has wronged repeatedly, especially in deciding his punishment.

In 1972, the Supreme Court struck down the death penalty as states then applied it because juries were imposing it arbitrarily and unpredictably, for crimes such as robbery as well as for murder. In 1976, when the Court reinstated the penalty, it upheld new state laws said to address those defects. These laws gave juries guidance about whether an “aggravating factor,” such as an “especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel” murder, justified the penalty, or “mitigating circumstances,” for instance if the defendant had “no significant history of prior criminal activity,” made the penalty excessive.

The reinstatement began an experiment, as the moderate justice Harry A. Blackmun called it, in devising rules “that would lend more than the mere appearance of fairness to the death penalty endeavor.” In 1994, in a dissent, Blackmun concluded that the experiment had failed: “No combination of procedural rules or substantive regulations,” he wrote, could “accurately and consistently determine which defendants ‘deserve’ to die.”

Blackmun’s declaration—“From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death”—followed the conclusions of three former justices, Lewis F. Powell Jr., a moderate conservative, and the liberals William J. Brennan Jr. and Thurgood Marshall, that the death penalty should be abolished. In 2008, Justice John Paul Stevens, a moderate conservative who became a moderate liberal as the court moved to the right, joined the group. He called the penalty “the pointless and needless extinction of life with only marginal contributions to any discernible social or public purposes.” In 2015, in a dissent, moderate liberal justices Stephen G. Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg indicated that they were the sixth and seventh recent justices who were ready to outlaw the penalty. Breyer wrote that “the death penalty, in and of itself, now likely constitutes a legally prohibited ‘cruel and unusual punishmen[t].’ ” He called for the Court to consider whether the penalty violates the Constitution.

Breyer noted that between 1994, when American support for the death penalty was at its all-time peak of around 80 percent, and 2014, when support had fallen to 55 percent, the share of Americans living in a state that had executed an inmate in the previous three years dropped from about one-half to a third. Since 2007, nine states have abolished the death penalty. Four states have established a moratorium on executions. In 2016, support for the death penalty fell to 49 percent, its lowest level in the four decades since the Court reinstated the punishment. The number ticked up to 54 percent in 2018, but fewer than half of Americans polled said they believed that the penalty was administered fairly.

The day before the presidential election in 2016, Carol S. Steiker of Harvard Law School and her brother Jordan M. Steiker of the University of Texas School of Law, the leading death-penalty scholars in the country, published a definitive account of the court’s experiment. In Courting Death: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment, they wrote that the “extraordinary phenomenon” of “justices of varying political commitments” embracing “constitutional abolition of the death penalty” suggested that the punishment would “not last much longer in the United States.”

But with the change in composition of the Court since that time, a firm conservative majority now favors the death penalty. In the past year, the penalty has been the subject of a series of prickly disputes between conservative justices, who blame frivolous appeals for long delays between conviction and execution, and liberal justices, who see the delays as many legal scholars do—as a reflection of an error-prone and unjust system.

As overall support for the death penalty has fallen in the past generation, Republican support has also declined, but modestly from 87 percent to 77 percent, compared with the dramatic drop in Democratic support from 71 percent to 35 percent. (Support of the crucial block of independents has dropped from 79 percent to 52 percent.) Still, the anti-death-penalty movement includes prominent conservatives who say the penalty should be abolished because it’s unfair, much too costly, and a burden rather than a balm to the families of victims of murder.

The Wardlow case doesn’t illustrate the worst forms of unfairness in the administration of the death penalty, such as that of Charles Ray Finch in North Carolina, who, last June, became the 166th person on death row in the past 46 years to be exonerated after a conviction and death sentence. Nor does it turn on the racial discrimination widely documented in the maladministration of the death penalty: of nine former inmates exonerated in North Carolina, seven, including Finch, were black.

The case instead shows failings at least as damaging to confidence in the criminal justice system: how easy it is for a state to make grave mistakes in a capital case while following legal steps that appear evenhanded, as Blackmun warned about—including when a defendant is white, as Wardlow is—and how hard it is to correct those mistakes by turning a sentence of death into life in prison, even when the mistakes are clear-cut.

Making grave mistakes is especially easy in Texas. According to a 2013 report by the American Bar Association, “Texas’s capital sentencing procedure is remarkably different from that of other jurisdictions,” putting the defendant’s supposed future dangerousness “at the center of the jury’s punishment decision.” With “no precise explanation” of what constitutes future dangerousness, jurors are left to interpret the concept “so broadly that a death sentence would be deemed warranted in virtually every capital murder case.”

In the Wardlow case, the jury wrongly predicted his future: despite the horrendous crime he committed as a teenager, he has become in middle age a trusted, peacemaking, and in many ways exemplary inmate—generous to others on death row, attentive to fellow prisoners and to others he exchanges letters with, and as engaged in the world as an inmate on death row can be who has spent much of the past 25 years in solitary confinement in a tiny cell.

In January 1993, Wardlow dropped out of Daingerfield High School, in Morris County, Texas, which includes Cason, where he grew up. His girlfriend and classmate, Tonya Fulfer, dropped out with him. She was a special-education student with a poor academic record and an IQ estimated at 80 to 85. He was a good high school student in the regular curriculum, a few credits shy of earning his diploma, with old IQ test scores of 97 and 109. Both were pictured in that year’s Pride, the school yearbook. He looks handsome despite the mullet typical of the time. Because of the shield created by her wide-rimmed glasses, she looks absent.

They appeared to be a mismatch, and yet they were inseparable. Both had been mistreated growing up: she “was the victim of physical abuse,” according to a doctor who examined her; he had been physically and psychologically abused by his unbalanced mother. Both felt that they didn’t belong.

They moved briefly to Fort Worth, doing odd jobs, but by June they were back home, with Wardlow broke but desperate to leave again. He decided to steal Carl Cole’s new 1993 Chevy Silverado pickup and drive it with Fulfer northwest to Montana so that they could start a new life far from their families. That was the impulse behind the crime. From his mother, he stole a Llama .45-caliber semiautomatic pistol intending, he says, to scare Cole, who lived nearby in Cason. Wardlow had already been in scrapes with the law, jailed briefly for speeding and not stopping for a cop and again for stealing a different pickup, but he had never been convicted and had never been charged with committing an act of violence against another person.

At his trial, Wardlow would testify that he knocked on Cole’s door shortly after dawn on June 14. When the old man answered, wearing a pajama top and undershorts, Wardlow said his car had broken down so he needed to call a friend. Cole handed him a phone, which wasn’t working because Wardlow had cut the phone line to the house. Wardlow, still outside, handed back the phone, and Cole set it down on a table and started to close the door. As Wardlow was asking if there was another phone he could use, he caught the door with his foot to keep it open. Cole said no and tried again to shut it. Wardlow pulled out the pistol—to intimidate Cole, he said. Cole surprised Wardlow by grabbing his arm and the gun, attempting to push him away. At five feet seven and 145 pounds, the 82-year-old Cole was a lot stronger than Wardlow expected. Though Wardlow was six feet four and 200 pounds, Cole forced him back awkwardly. What happened next was the heart of the crime. In the trial it was fundamentally disputed—with evidence Wardlow gave presented by each side in his trial.

Wardlow testified that when Cole pushed him, he thought he was losing his grip on the gun and panicked, fearing that the older man would grab it and shoot him. To convince Cole he wasn’t “playing,” so that Cole would let go and back up, Wardlow pulled the trigger without aiming. The bullet hit the older man between the eyes and killed him on the spot. Wardlow found a comforter in the house to wrap Cole’s body in and stood it in a closet. He took Cole’s billfold, which contained $147. Fulfer and he headed to the truck. They already knew the keys were there. At around 3 A.M. that morning, they had done some scouting and found the truck unlocked and the keys in it. They didn’t take the truck then, Wardlow testified at his trial, because they decided they needed to tie Cole up or take him with them, so they could get far away before the police learned about the robbery. He and Fulfer headed north.

The next day, in Norfolk, Nebraska, about 800 miles from Cason, they traded the gas-guzzling truck for a black Mustang convertible and $8,000. That day, his mother reported to the local sheriff that Billy had stolen her gun, so now the police in many states were looking for him as Cole’s likely killer. The following day, across Nebraska’s northern border in Madison, South Dakota, police surrounded Wardlow and Fulfer, and the two surrendered. The police found a pistol under the passenger seat and later determined that the gun had fired the bullet recovered from Cole’s body. A week or so after the arrest, Wardlow was returned to Texas and charged with capital murder.

Wardlow says he experienced the next year as an endless nightmare. He knew that he had done something terribly wrong and felt remorse—overwhelming guilt, shame, and regret. He had nightmares about killing someone. Sometimes he went for days and days without sleeping, and then slept for two or three days. After he had been in jail for about nine months, the sheriff, Ricky Blackburn, whom Wardlow had known since he was a boy, told Billy that when he himself wrote out what was bothering him, it helped him “get right with God.” Wardlow trusted Blackburn, so he did what the sheriff proposed and wrote.

In retrospect, he felt manipulated—not coerced, yet cajoled into doing something directly against his interest. Instead of a therapeutic exercise intended to help him cope with the tragedy he had created for the Cole family, his own family, Fulfer, and himself, the writing became, once the prosecutor obtained it from the sheriff, a court document. The prosecutor based his case on it, depicting Wardlow as a cold-blooded killer. Wardlow had written, “Being younger and stronger, I pushed him off and shot him right between the eyes. Just because he pissed me off. He was shot like an executioner would have done it. He fell to the ground lifeless and didn’t even wiggle a hair.”

Wardlow took full responsibility for what had happened by erasing Fulfer from the scene. “My girlfriend,” he wrote, “followed me to my neighbor’s house and there she stayed until I came back with the truck.” Six months later, in a letter to the sheriff, Wardlow recanted what he had written about his intent to kill Cole, as well as what he had written about Fulfer. “That statement was true in most areas,” he wrote, “but left out some facts or bent the truth to make Tonya appear uninvolved.” He went on, “The plan I had discussed with Tonya involved going to Mr. Cole’s house and robbing him, tieing him up, taking him with us in his truck, and leaving him somewhere away from the main road or a phone.”

Fulfer had been with him at Cole’s house, Wardlow wrote, including when he shot the old man. At her sentencing hearing, she testified that she had been standing right behind Wardlow when he knocked on Cole’s door and then ran into a nearby carport when her boyfriend drew the gun. She hadn’t seen the hand-to-hand part of the struggle, but she testified repeatedly that neither she nor Wardlow had intended to kill Cole. They had planned to steal the truck without shooting anyone.

After Wardlow’s trial, his lawyers learned that if Fulfer had testified, as the lead lawyer Bird Old III explained in an affidavit in 2001, she “would have supported Billy’s testimony about a struggle with Mr. Cole over the gun just before the gun fired.” Instead, Old implied, the prosecutor violated Wardlow’s right to due process by interfering with Fulfer’s choice about whether to testify on his behalf.

The prosecutor had tried to turn Fulfer into a witness for the state. When that failed, he offered a plea bargain—to go into effect after Wardlow was tried, convicted, and sentenced. Two months after his sentencing, she pleaded guilty to murder and received her own sentence of 18 years in prison. The result of the delay, Wardlow’s current lawyers argue, was coercion not to testify for him, because if she had, she risked losing her plea deal. She was released in 2009, four years before the end of her sentence.

In his affidavit, Old also said that he had talked to Wardlow’s parents, Lynda and Jimmy, about how they would testify if he called them as witnesses:

I concluded they were loose cannons and would not make good witnesses. Billy’s mother appeared unstable and very unpredictable. Physically, they didn’t have a good appearance and I did not think that their demeanor was appealing. Some of the information they gave me about Billy was inconsistent. Also, [Lynda] had helped the sheriff find Billy.

Old had no previous experience in a capital trial, so he didn’t appreciate that the reasons he thought Wardlow’s parents would be harmful witnesses were in truth reasons why they had the potential to be helpful to their son by providing mitigating evidence. What made them—Lynda especially—repellent could have been the basis for an argument about why their son should not receive a death sentence.

The most chilling testimony for the state came from Royce Smithey, an investigator for a group that prosecutes felony crimes committed in Texas prisons. If the jury sentenced Wardlow to death, the investigator said, he would be “segregated” and “severely restricted” until he was executed. He would have limited access to prison employees whom he might harm. Solitary confinement on death row would punish Wardlow and protect prison employees from the continuing danger he represented, Smithey testified. But if the jury gave him a life sentence, he asserted, Wardlow would be released into the general prison population with other felony offenders.

Recently, Frank G. Aubuchon, who was a correctional officer and an administrator with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) for more than 26 years, reviewed Smithey’s testimony at the request of Wardlow’s current lawyers. Aubuchon wrote, “Mr. Smithey’s multiple falsehoods served to mislead the jury into believing that TDCJ would be completely unprepared to imprison Mr. Wardlow in a secure environment unless he received a death sentence. Based on my decades of experience as a TDCJ corrections officer, administrator, and prison classifications expert, I can say that this is categorically false.”

But Smithey’s testimony was uncontested at the trial and made a life sentence for Wardlow sound like a serious threat to others. It would give him the chance to harm other people, perhaps even to kill again. The testimony made a life sentence sound like a reward for Wardlow, not an endless punishment.

Mitigating evidence that can lead to the less extreme sentence of life in prison can be a defendant’s lack of any prior conviction, extensive abuse as a child, serious mental problems, or a show of remorse. In the Wardlow case, all of those mitigating factors were present, and should have been sufficient to make his punishment life in prison. Wardlow’s trial lawyers didn’t seek that evidence in preparing his case, and so didn’t present it to the judge and jury; they didn’t even know whether they had it available to them.

Wardlow grew up poor, living with his family in a small, one-story, ill-kept house. His father, Jimmy, earned a meager income working odd jobs as an electrician and a carpenter, and Lynda worked as the caretaker of the Cason Cemetery. Together, they operated the Cason volunteer fire department. Tall and big-boned, she was unpredictable and explosive, frightening to almost everyone including, it turns out, herself.

In an affidavit from 2001, Lynda, who died in 2013, testified,

I have a violent temper. When I really lose my temper, it brings on a strange power surge. My eyes dilate and I have superhuman strength. For example, once I was angry because Billy Joe was putting his pickup on blocks and wouldn’t listen to me when I kept telling him to stop. … I hollered at him and when he ignored me, I … picked up the side of the truck and told him that if he didn’t stop, I would turn the truck over. I couldn’t believe it when I saw what I was doing. It is scary to me. It’s like there is a part of me that I can’t control.

Lynda also said that she long “felt like I possess special powers.” Her temper was one of them. “Sometimes I call it the beast within and other times I refer to it as the Force,” which told “me to do things and I talk back to it.” She testified that she had “seen what I believe to be a UFO a number of times” and “once I was abducted by aliens.” The abduction “lasted about 2 hours.”

In June 1998, Paula K. Lundberg-Love, a psychologist and professor at the University of Texas at Tyler, conducted a psychological assessment of Billy Joe Wardlow, who was then 23. Lundberg-Love said in an affidavit in 2001 that her goal had been to determine whether he had “suffered from any mental disorders that may have contributed to the offense.” She reviewed his social history, the details of his case, his school records, and other information about him. She spent hours interviewing him, administering psychological tests, and interviewing Lynda and Jimmy.

She concluded that Wardlow had post-traumatic stress disorder from his childhood and a host of related psychological problems, which supported what Richard Burr wrote in a brief: “The killing of Cole was born from the poverty, social isolation, childhood abuse, and mental disorders of Wardlow and his equally young girlfriend Tonya Fulfer.”

When Billy was a boy, Lynda had told him the UFO story. As she said to the psychologist, he got confused and thought he was the son of an alien. He told Lundberg-Love that “he had lived in constant fear” that his alien father would come and take him away. Sometimes he was afraid to leave his house. The psychologist wrote that Lynda was “overly protective” of Billy, so he “did not become included in a social peer group, did not develop friendships, felt very different from other children and did not develop particularly close relationships with anyone outside of his family. Indeed, Billy was painfully aware of the fact that he was socially isolated and socially inept. Machines were his friends.”

Billy was also “late reaching some developmental milestones”: he was, at 19 months old, late walking. He was a bed wetter until he was 10. To shame him into stopping, Lynda made him wear his wet underwear on his head.

In people who are developmentally delayed, who suffer abuse and neglect, or both, according to experts on the juvenile brain, the connections between the emotional centers of the brain and the cognitive centers, which normally don’t consolidate until about age 25, solidify even more slowly, extending the period of impulsiveness and lack of awareness of consequences. For them, the storm and stress of adolescence—when the rate of preventable deaths from accident, homicide, and suicide triples—can continue longer and the capacity to control their behavior in the face of strong emotions can develop more slowly. Wardlow tried to commit suicide six times by the age of 20. When he was 15, his mother found him in the act, handed him her .45 pistol, and told him to shoot her, because if he killed himself he would be killing her. About 15 months later, after Fulfer and he had gotten together, they had an argument and he again tried to shoot himself, but the gun didn’t fire. In the weeks before he killed Cole, he tried to drive a stolen truck off a bridge. Then, once he was in jail for the murder, he tried to kill himself three more times before he got to death row.

Lundberg-Love found that he “was likely to exhibit illogical, tangential and disorganized thought processes” and “was rather high-strung, felt emotions more intensely than others do, reported difficulty controlling his anger, and tended to feel lonely and misunderstood.” She also said that he “was preoccupied with bizarre ideas, abstract thoughts, and probably experienced delusions and hallucinations.” She detected “low morale and a depressed mood” as well as “a tendency toward obsessiveness and indecision.” Finally, she noted, “Billy Joe has viewed the world as an unsafe place.”

When Wardlow arrived on death row in 1995, he was a tall, skinny, 20-year-old with a “nervous stare,” as his friend and fellow death-row inmate Mark Robertson put it in a letter to me. He “had a lot to figure out in prison life, including how to survive and get along with his peers, how to stay alive legally, so to speak, and how to get a bearing on his own sense of ethics.” After two years there, Wardlow wrote a letter to Charles Cole, the son of the man he killed: “I first wish to express my deepest apologies for being responsible for the death of your father,” Wardlow wrote in June 1997. “I never went there with any intent to kill your father, but everything I said about the struggle was true. I can never express how sorry I am for what happened to your father, but I ask that you hold no animosity towards my family.”

Robertson and other friends of Wardlow’s on death row who wrote to me about him at my request emphasized that, as he grew into himself, he developed a hunger for learning—astronomy and astrology at first—then “classical physics and some quantum theory via the books written for laypersons” and through a weekly radio show called Science Fantastic. Soon after he arrived on death row, Wardlow mastered the manufacturer’s repair manual for Smith Corona word processors and repaired broken machines. On death row, he is considered an electronics wizard.

“Billy went from this young, guarded, somewhat introverted personality,” Robertson wrote, “to this more open, opinionated, optimistic, radiant mind.” Wardlow is meticulous about cleaning the showers for his cell block, tracking his correspondence with pen pals, and listening to his friends on death row when they tell him about their worst fears, like the erosion of their ability to think from years in solitary confinement. “We control so little in here,” Robertson wrote, “but I’ve learned from him that the one thing we do control is ourselves and one little personal microcosm—and it all starts there and radiates out from there.”

Another inmate, Tony Egbuna Ford, told me that death row in Texas is often divided along racial lines—45 percent of the inmates are black, 27 percent Latino, and 26 percent white. Inmates see themselves as members of separate interest groups. “Prison,” he wrote, “really makes racial cooperation something to be frowned on.” But Ford recalled, when a group of guards came to get Wardlow at a shared rec yard, looking for a fight, the yard “was filled with a bunch of black guys.” The guards were “forceful” with Wardlow. “He was cool, not arguing with them or anything,” but he asked why they were after him.

This riled up the guys on the yard and so they started surrounding the rec yard, and grumbling about, ‘They trying to fuk over Billy. He’s one of the good guys …’ One of the guards I guess snapped to what would happen if they beat Billy there on the yard. He brought this to the sgt’s attention, and then looking around. Assessing the situation. Asked Billy if he would please come with him. Billy said sure, and left without harm. Billy is the only person who could’ve inspired people of a different race to come to his aid if needed.

“Billy has this straight forward way of talking to me and everyone,” Ford wrote. “He looks you in the eyes. Normally he has this smile on his face, and despite all the years of being here in this hell, Billy still looks pretty much like a big kid. But when he is serious and he talks with you, he talks TO YOU. His energy will slow. And before you know it, it is like you both are in sync breathing. You are calm. And he talks, and you understand.”

In Texas, some inmates mark the start of their time on death row by the number of the state’s most recent execution. By this reckoning, execution one happened in 1982, 10 years after the Supreme Court halted capital punishment and six years after the Court allowed it again. Wardlow has been on death row since execution 90 of the 567 that Texas carried out between 1982 and October 2019. The average time from arrival to execution is around 11 years, and the longest was 31 years. Wardlow has been waiting for 25 years.

At the end of October, Texas held 210 men on death row. “We know what the state of Texas plans for us,” wrote fellow inmate Moises Mendoza, “and so we just try to live in such a way as to prove we are NOT that animal we were portrayed as.” Men who have been on death row as long as Wardlow and Mendoza have spent a lot of time around hundreds of men who were later executed.

One way inmates at Polunsky deal with the likelihood of being put to death is by playing the tabletop fantasy game Dungeons & Dragons. Every player pretends to be a character and goes on an adventure with other players. A dungeon master orchestrates a game, creating the story for a campaign and refereeing among the players. The task is to reach goals the master sets by cooperating through storytelling. Inmates can play with each other despite spending at least 22 hours a day alone in their cells because the dayrooms, or indoor rec spaces, are in front of cells. Inmates devoted to the game call themselves geeks. Wardlow is the master.

To Ford, on death row since execution 61 in 1993, the way Wardlow runs a game, it “is not just a game. It’s a very unique way in which guys back here accept criticism of their actions, in ways that other than the D&D setting, they would not.” Wardlow challenges aggressive moves that players make. He gets them “to think about their actions” without picking on anyone. Players trust him: “And you can see how people feel after playing in D&D sessions with him. They are happier. They want to talk about ‘what their character did.’ They are much more social, and they can’t wait until the next D&D session. With Billy, D&D has become our therapy.”

Wardlow has “had his problems,” Ford acknowledged in a letter to me. Some prison guards, Ford explained, think that a person convicted of murder and sentenced to death “can’t possibly be a good person.” Some guards try Wardlow—“try and rattle him or set him up” so that they can discipline him. He has an official disciplinary record—18 offenses in almost 25 years. One of his worst offenses in prison likely came in 1996 when he was 21. It was strikingly mild. He was written up for possessing contraband, including a homemade heating coil for boiling water, a cardboard tube with speakers, a headphone cord, a night-light, a radio amplifier, and a radio. In 2011, he got written up for not taking his towel off the door of his cell. In 2016, it was contraband again—“3 stamps.”

Within the merciless confines of death row, which friends of his there described as “a cesspool,” “a dark and dank hell,” and “a house of horrors,” where breakfast usually arrives by 3:30 A.M., lunch by 10 A.M., and dinner by 3 P.M., these minor-seeming charges and the discipline they lead to yield another revelation of character. Ford wrote, “I think the things that really sets him apart in another way is that he don’t fall for these things. He will still talk to guards who act this way where most people back here will show obvious hostility. They will curse, and yell. They will threaten. Billy won’t do this.” He respects guards, calling them “sir” or “ma’am.” As a result, “The guards respect him.”

He hasn’t joined a prison gang. He hasn’t padded his résumé, as one of his friends put it, by making the crime that landed him there even more horrendous than it was. He speaks about it quietly, with intense regret. He hasn’t become “all religious so that people will respect him,” Ford wrote. “But he has morals and principles. Billy has a feel for people. He has this way to empathize with people, especially when they are hurting.” He concluded, “Billy IS one of the good guys. Billy DOES NOT belong here. And it is my deepest hope and prayer, that he is able to live his life, and not be another statistic for the Texas death penalty.”

At 75, Mandy Welch is a cofounder of the Texas Defender Service, a nonprofit in Houston and Austin dedicated to a fair and just criminal justice system in Texas. It provides legal representation for indigents in death penalty cases and trains lawyers in handling them. For 40 years, she has represented poor people—and since 1996 with her husband, Richard Burr—almost always in capital cases. They live on a farm not far from the Polunsky Unit. Burr, 70, is a former director of the Capital Punishment Project of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. He has defended inmates on death row, who are invariably poor and often black or Latino, because he believes they most need his help as a lawyer. Welch and Burr have billed state and federal courts for about 700 hours over the years for work on Wardlow’s behalf and have devoted another 500 hours without pay.

Last May, Burr filed Wardlow’s last federal appeal. It was a petition asking the Supreme Court to review a decision not to hear the case made in 2018 by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which includes Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, based on the view that “the Fifth Circuit disregarded, flouted, or paid mere lip service to every applicable decision”—10 in all—by the Supreme Court in this denial. Burr asked the Court to send the case back to the Fifth Circuit for consideration of the law in the case as if for the first time.

Burr expected the Supreme Court to deny the petition because it didn’t challenge a problem of widespread legal concern and because the chance of the Court’s granting a petition in any criminal case is very low. In 2017, the Court granted 1.8 percent of all criminal petitions. In mid-October, the Court announced without comment that it would not take up the appeal. That doesn’t mean Wardlow’s appeal was frivolous. The heart of the petition was that the Fifth Circuit—a federal court—made up a state rule of legal procedure, which the Texas legislature never created and no Texas court ever established, to deny Wardlow his right to state and federal reviews of his case under state and federal writs of habeas corpus.

In Texas, and in the 28 other states that now have the death penalty, capital cases are almost always like this one—about knotty, often picayune-seeming issues of legal procedure. Each step is supposed to protect a defendant’s rights, but today in death penalty cases legal procedure heavily favors the state. A 1996 federal statute called the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, known by its acronym AEDPA (pronounced ED-pa), requires favoring the state over the defendant in capital cases and also in other criminal matters.

At the heart of AEDPA are two stringent provisions. One says that even when a state court misapplies the Constitution, a defendant cannot necessarily have his day in federal court. He must prove that the decision of the state court was “contrary to” what the Supreme Court said is “clearly established Federal law,” or that the state court’s decision was “an unreasonable application” of it. The other says that even when a state court makes a questionable determination of facts—for example, that it made no difference in the conviction of a Latino man for murder in California that the prosecution kept off the jury each of the seven Latinos or blacks in the jury pool of more than 200 people—a defendant must prove, again, that the court’s determination was “unreasonable.” A federal court must uphold a “reasonable” decision of a state trial court, in other words, even when it is wrong.

The first restriction greatly reduces the power of a federal trial court to hold a state accountable under the Constitution. The second restriction is a severe limit on the power of federal courts to consider new factual evidence that could exonerate a prisoner or change his sentence from death to life in prison. Death penalty litigation is endless because legal procedure is basically a set of obstacles for death row inmates.

AEDPA accelerated executions when it went into effect in 1996: 78 percent of all those executed in the United States since 1976 have come under AEDPA. Of those executed since AEDPA, Texas was responsible for 39 percent, even though Texans account for only about nine percent of all Americans. That makes Texas the capital of capital punishment in the United States. Texas executed more than half of those put to death nationwide in 2018. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, the state is executing “the most vulnerable prisoners and prisoners who were provided the worst legal process.”

In “A Broken System,” a research paper published in 2000, James Liebman of Columbia Law School and his coauthors reported that “courts found serious, reversible error in nearly 7 of every 10 of the thousands of capital sentences that were fully reviewed” between 1973 and the year before AEDPA became law. After AEDPA, without any apparent change in the state courts, the rate of reversals fell by about 40 percent. AEDPA likely keeps courts from catching many serious errors.

The most common errors that courts did catch in death penalty cases were “egregiously incompetent” defense lawyering and “prosecutorial suppression of evidence of innocence or that death is not a proper penalty.” The reason for the errors, overall, had to do with volume: “The higher the rate at which a state or county imposes death verdicts, the greater the probability that each death verdict will have to be reversed because of serious error.”

The Wardlow case reflects the most common errors—prosecutorial sandbagging of critical evidence, in preventing from testifying the only witness who could say that Wardlow didn’t intend to kill Cole; and egregiously incompetent defense lawyering, in not seeking and presenting mitigating evidence, of which there was a small mountain.

The week after the Supreme Court denied Wardlow’s appeal in October, Burr filed with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals an argument about why it would be cruel and unusual punishment to execute Wardlow, based on what the U.S. Supreme Court, in 2005, held about punishment for murders committed by people when they were 17 years old or younger.

In a landmark case called Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court ruled that it is unconstitutional to execute anyone who was under 18 at the time of the crime, because that person “cannot with reliability be classified among the worst offenders.” The Court recognized even then that “drawing the line” at that age was open to discussion because the “qualities that distinguish juveniles from adults do not disappear when an individual turns 18.” Roper was the first case in which developmental science provided a foundation for a ruling of the Supreme Court. The majority opinion observed, “The reality that juveniles still struggle to define their identity means it is less supportable to conclude that even a heinous crime committed by a juvenile is evidence of irretrievably depraved character.”

When Wardlow committed his crime, he had the kind of still-developing brain that Justice Elena Kagan described in 2012 when the Supreme Court held that it was unconstitutional to sentence people to life in prison without parole for murders they committed when they were under 18. “Mandatory life without parole for a juvenile precludes consideration of his chronological age and its hallmark features—among them, immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences,” Justice Kagan wrote. “It prevents taking into account the family and home environment that surrounds him—and from which he cannot usually extricate himself—no matter how brutal or dysfunctional.” Kagan instructed that a state must provide inmates sentenced to life in prison for a crime committed as a youth “some meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.”

In 2018, a federal trial court in Connecticut applied that standard to an inmate who was 18 when he committed murder and was sentenced to life in prison without parole. The judge in that case wrote, “The science indicates that the same indicia of youth that made mandatory life imprisonment without parole unconstitutional for those under the age of 18” applies to 18-year-olds. That defendant was 18 years, 20 weeks old when he killed someone. Wardlow was 18 years, 29 weeks old when he did. The argument that applies to a parole hearing should apply even more strongly to a death sentence.

In 2019, John Blume of Cornell Law School, who is a leading scholar on the death penalty, and his colleagues published an article arguing why Roper’s ban against execution of juveniles who were under 18 at the time of their crime should be extended to those who were under 21, as Wardlow was. They wrote, “The brains of people under 21, unlike adults’ brains but like teenagers’ brains, are capable of triggering adult emotions but are not capable of managing or processing those emotions.”

Today, Wardlow’s maturity and his rehabilitation reinforce how ill-equipped the jury was to decide whether, in the future, he “would constitute a continuing threat to society.” When he committed his crime, he was a headstrong 18-year-old, arguably with the level of irresponsibility of someone younger because of the delay in his development and his traumatic childhood. He did not grow up until he was on death row.

In the argument that Burr filed in October, he writes that “new research findings by the neurosciences,” as the Supreme Court has recognized, “further corroborate and give meaning to the Court’s recognition that turning 18 does not turn a youth into an adult.” He goes on, “The qualities of people this age that were recognized by the Supreme Court as the reason for precluding the death penalty included, most importantly for Mr. Wardlow’s claim, the unformed nature of their character and the likelihood that their character would change as they matured.”

All of that leads to the claim he made on Wardlow’s behalf: “The prediction of future dangerousness called for by the Texas capital sentencing statute cannot reliably be made for a capital defendant under 21 years old.” The Texas statute, as applied to young people under 21, is unconstitutional based on recently affirmed science.

The state responded by proposing the date for Wardlow’s execution.

Last June, I met with Billy Joe Wardlow at the Polunsky Unit. We were separated by shatterproof glass. I was in an open-ended cubicle, and he was locked into a cubicle that had been made into a cage. It was too small for his six feet, five inches—he had grown an inch since the time of his crime—so he stooped as he leaned forward to talk with me on a landline phone.

He wore a white jumpsuit. His reddish-brown hair was trimmed short, and his fingernails were immaculate. His blue eyes seemed to express an intense need for human connection. With a Texas twang in his lilting tenor voice, Wardlow spoke hurriedly, like a man who didn’t have much time.

Sometimes in our conversation, Wardlow went on about people he assumed I knew of but didn’t. Sometimes he commented on pivotal moments in his case. The words kept pouring out of him. Toward the end of the hour we were allowed to spend together, Wardlow recounted for me the minutes that took a life and ravaged his own. By then in my conversations with his lawyers and friends, I had heard a half-dozen accounts of the crime, based on court opinions and Wardlow’s conversations with others. No one had mentioned what he wanted to make sure I knew—that during the crime, he had thought of walking away. At this juncture in our conversation, he became again, somehow, the immature, impulsive, and risk-blind youth he was on the morning of the crime, a young man who couldn’t stop himself.

He said, “But yeah, it was about a week before [when] I decided, you know, ‘I want to rob this old man and try to steal his truck and we can run away to Montana.’ And that was just this vague idea that I thought I could kind of feel my way through once everything started. And yeah, it, it obviously didn’t pan out: it was really, really, really stupid. I look back on it and I had chances to back down and I just, I was, I don’t know, I was persistent.”

He described how, when Cole handed him the cordless phone, for the first time it occurred to him to just walk away: “I knew it wasn’t going to work, so I’ll pick it up and I’ll dial it and I’ll fake and act like it works and it’s in my mind, ‘Back down. Go home. Leave it alone.’ I didn’t do it. I had a chance and I didn’t do it. I was fucking stupid.”

He continued, “I told him, I said, ‘The phone doesn’t work, so the batteries must be dead or something.’ He was like, ‘It doesn’t have any batteries.’ And he takes it back. And then once again I’m like, ‘Just let it go.’ But I didn’t, I was just thinking in my mind, ‘Okay, if I do this, this is going to be the end. Tonya’s going to be gone. I’m going to just be on my own again.’ ”

Now, he was looking toward me but not at me. Uneasiness pinched his voice and face. He continued:

So it’s kind of rattling through my mind. Okay. So, I reached into my waistband and pulled out a pistol. I had Mom’s .45 and then I racked a shell into the chamber just to show for emphasis, This is a real gun, this isn’t a toy. And then when I raised it and pointed at him, he jumped on me. He tried to take the gun out of my hand. He grabbed my forearm and he grabbed the pistol and I’m standing on this top of, like, three steps. I certainly didn’t expect someone to try to take the gun. In my mind, I’m thinking, from watching TV, if you pointed a gun at someone they’re going to capitulate, they’re going to do whatever you ask them to. But he didn’t have that idea in mind.

“Maybe he was afraid. Something that Dick and I talked about”—he meant his lawyer, Richard Burr.

And he said I couldn’t possibly have accounted for the fear of someone being threatened with their own life. And you put a gun in someone’s face, they’re going to be terrified. So, really, two terrified people fighting over a gun is what it was. A terrified old man and a terrified kid. And the old man was winning. And when he started to take the gun out of my hand, I can remember I put my finger into the trigger, and pulled the trigger.

And I can remember the gun went off and hit him in the face and I couldn’t do anything about it. And Tonya comes into the carport sometime later, I can still see it today. Twenty-six years later, I can still see him lying there dead and I did it. It was my hand on the gun. I’m standing there holding the gun and I’m looking at this guy and I don’t know what to do. I’m just shocked. I’m just … and, then Tonya comes in and she’s like, “We gotta go. We can’t stay here. We got to go.”

He was weeping now on the other side of the glass.

“I knew I had done something really terrible and I needed someone to absolve me of that. I can remember Tonya holding me, she’s crying with me. She’s, like, ‘It’s okay.’ I was like a burbling infant because, still, I didn’t mean to do it. I didn’t mean to, I didn’t mean to shoot him. I didn’t mean to do it.”