Thoreau’s Pencils

How might a newly discovered connection to slavery change our understanding of an abolitionist hero and his writing?

When Henry Thoreau was a boy, he asked his mother, Cynthia, what he should do when he grew up. “You can buckle on your knapsack,” she told him, “and roam abroad to seek your fortune.” It was a familiar route into the world for second sons especially, but for Henry the possibility was too awful to contemplate. As tears filled his eyes, his older sister, Helen, came to his rescue. “No,” she assured him, “you shall not go: You shall stay at home and live with us.” So Henry did, virtually all his life, and paid his way in pencils.

John Thoreau, Henry’s father, had entered the pencil business in 1823, after his brother-in-law happened upon a vein of plumbago, or graphite, in the New Hampshire hills. By then, John and Cynthia had four children, including Henry, and needed a lucky break. As a young man, John had borrowed against his expected inheritance to open a store. But the early death of his father, combined with mismanagement of the family estate, meant that John’s inheritance never came through. His store failed, and afterward he struggled to earn a living beyond his debt by clerking, farming, and ultimately selling his gold wedding ring.

Once John got started in pencils, he and Cynthia were determined to recover the economic security and social standing they had lost. Pencils made by the family firm, initially called J. Thoreau & Co., quickly gained local recognition, winning an award in the first year of production, but financial success still proved elusive.

More than a decade later, John proposed that Henry apprentice himself to a cabinetmaker—sensible training for a future pencil manufacturer. But when Henry passed Harvard’s entrance exam in 1833, Cynthia insisted that he attend, even if sending him to the college would be a financial stretch. In 1835, near the end of Henry’s second year, the Thoreaus gave up their brick house in Concord and moved into a smaller one with two of John’s spinster sisters.

Fifteen miles away in Cambridge, Henry felt their sacrifice keenly. In November 1835, the Board of Overseers of Harvard College voted to allow enrolled students to take up to 13 weeks off to earn money teaching, and Henry was one of the first to apply for leave. A month later, he became the master of a one-room schoolhouse and 70 boys in Canton, about 20 miles to the south. By the time he returned to Cambridge in the spring, he had acquired a new contempt for Harvard’s classical curriculum as well as symptoms of what historians now think was the tuberculosis that would eventually kill him.

In May 1836, increasingly sick, Henry left Harvard again, and this time it wasn’t clear whether he would be going back—whether he had the strength, or his family the money. Late in the summer, just before the start of the fall term, Henry and his father packed up boxes of pencils and set out on a trip to New York, where they hoped to earn money for tuition.

Henry returned to Cambridge that fall with mixed feelings. He finished 19th in his graduating class of 41, good enough to earn him a prize of $25 and a prestigious speaking role in the commencement ceremony. He and two other students were assigned to speak on a theme of special relevance: “The Commercial Spirit of Modern Times, Considered in Its Influence on the Political, Moral, and Literary Character of a Nation.” Many members of his class were struggling to find jobs amid an economic crisis that would come to be known as the Panic of 1837. Thoreau wondered whether they should even be trying. He had a job in the pencil factory waiting for him, but he wanted nothing to do with it.

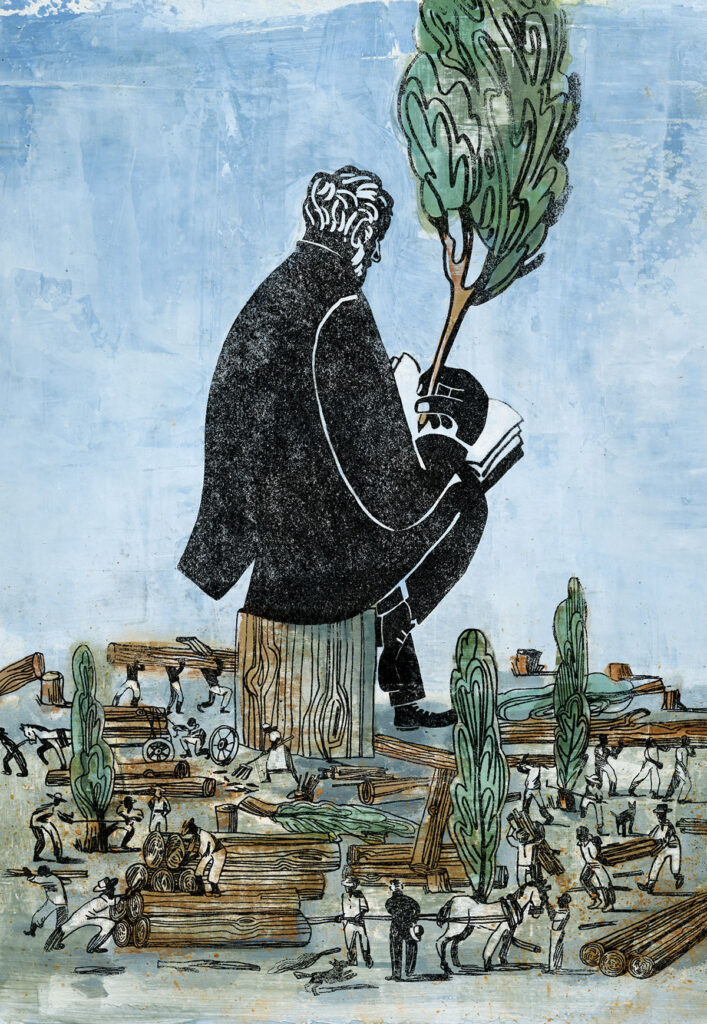

Imagine looking down at Earth from “an observatory above the stars,” Thoreau asked the hundreds assembled for the graduation ceremony. How would this “beehive of ours” appear from that height? Men “hammering and chipping, baking and brewing … scraping together a little of the gilded dust upon its surface”—precisely what his father did all day while mixing graphite dust into pencil leads. For Henry, these working men had given away the most important thing they possessed: their freedom. The commercial spirit, Thoreau argued, was too much “the ruling spirit.” Its triumph had made every man “a slave of matter.”

After graduation, Henry started a teaching job in Concord, only to quit 10 days into the academic year rather than continue to discipline his students with a ferule, as ordered by the town. He appealed to friends for word of other openings, but none appeared. Out of options, he joined his father in the pencil factory after all.

That autumn, Henry started to dig into the complex technical problems that had made American pencils notoriously “coarse, brittle, greasy, and scratchy,” as Thoreau biographer Laura Dassow Walls describes them, especially compared with European imports. Possibly through research in the Harvard library, Henry developed a formula for kiln-fired pencil leads—a mix of finely ground graphite and clay—that could be reliably graded from hard to soft. The improved Thoreau product appealed especially to engineers, surveyors, carpenters, and artists who valued its consistency.

After this initial success, Henry tried to get away again. In 1838, he returned to teaching and later opened a school with his brother, John. They taught together until John Jr.’s health—he, too, suffered from tuberculosis—worsened. In January 1842, John died of tetanus, and before long, Henry found himself back in his father’s factory. “I have been making pencils all day,” he wrote with resignation in his journal that March.

In 1844, Henry made another breakthrough, inventing a grinding machine that produced exceptionally fine graphite powder—the key to a strong, even point, and in turn a clear, steady line. On the strength of these innovations, Thoreau pencils won more awards in 1847 and 1849, and they were celebrated as the equal of any English ones. No one in the United States made better pencils than the Thoreaus, and the reason for their success was Henry.

His inventions helped to lift his family into Concord’s comfortable middle class. In 1849, the Thoreaus bought a large house on Main Street, and Henry helped attach the pencil factory sheds to the back. Inside, a fine graphite dust coated all the furniture. Around the same time, John Thoreau changed the name of the family business from J. Thoreau & Co. to J. Thoreau & Son.

And yet, for all their technical complexity, the manufacturing solutions that Henry came up with didn’t address the greatest challenge of pencil making—one that scholars of Thoreau’s life and work have long overlooked. Making high-quality pencils in the middle of the 19th century required a special kind of wood from a tree that grew in the southern states, especially in Florida and around the Gulf of Mexico, where it was harvested and prepared by enslaved workers.

In the first half of the 19th century, Concord was “the birthplace of American pencil-making,” according to historian Robert A. Gross. At one point, 13 pencil makers were at work in and around the town. The first and largest of them, William Munroe, had ended up in the business by accident. A cabinetmaker by trade, Munroe turned to pencils in 1812, taking advantage of a wartime opportunity. By the middle of the 1820s, Munroe was selling hundreds of thousands of pencils each year, all over the country, and climbing the economic ladder of Concord.

Munroe’s success surely inspired John Thoreau. Gross has shown that John probably poached Munroe’s trade secrets in 1823 to get a jump-start in the business. Yet despite Munroe’s ingenuity and experience, there was one part of pencil making that he always considered his “greatest difficulty,” no matter what innovations or improvements he made to his manufacturing process: where to find the wood.

When Munroe was making furniture, wood hadn’t been an issue. He got the cheap, common stock—pine for furniture and coffins—from local forests and sawmills. He got expensive specialty lumber—mahogany for chests and clock cases—from merchants connected to ports, including Boston, where ships offloaded tropical hardwoods alongside sugar and other prized Caribbean commodities. Yet pencils were a different story.

Munroe described his tentative entrance into the trade in his unpublished autobiography, written primarily in the late 1830s. Without too much difficulty, he had established that the wood pencil casings his European competitors used were cedar. What he didn’t know, despite his experience as a cabinetmaker, was that the two most common varieties of cedar—red and white—differ significantly. This he learned only after he went looking for cedar in the swamps around Concord, found some white cedar boards at a local sawmill, and bought up as much as he could, thinking himself lucky. When he got the boards back to his workshop, he realized that the light, brittle wood wasn’t the right kind for pencils at all.

Red cedar was more difficult to source than white, but not because it was scarce. On the contrary, the tree usually called red cedar—Juniperus virginiana, actually a variety of cypress—is one of the most widely dispersed on the North American continent, covering the eastern seaboard from southern Canada to southern Florida. As Henry Thoreau noted in his journals, there was red cedar growing around Walden Pond. Munroe found some in the woods outside Concord, but the problem again had to do with quality.

Northern climates compress the cedar growing season, compacting the trunks, cinching and skewing the grain. Exposed to New England winters, red cedar can grow into a spectacularly gnarled and contorted tree—rich in regional symbolism, but useless for pencils. By contrast, in warmer southern climates, red cedar grows tall and straight, its trunk clear of branches far off the ground, its soft but durable heartwood run through with a long, even grain, softening as it ages. With precious little good wood to be found locally, Munroe learned that what he needed was “Mobile cedar”—that is, logs shipped out of that port on Alabama’s Gulf Coast.

Cedar came from Mobile because cotton did. The district that became Alabama had once been a Spanish colony and an independent republic. By 1798, it was part of the Mississippi territory, though more sparsely settled than the western sections on the river above New Orleans. That changed with the “Alabama Fever” of 1817, when settlers and speculators rushed in to claim a patch of the newly established U.S. territory. They had their eyes on cotton land, and the migration of would-be planters only accelerated after statehood in 1819. In 1810, Alabama’s population had been estimated at less than 10,000. In 1830, by the time of the Indian Removal Act, it was more than 300,000. The land these new arrivals favored, hugging the rivers north of Mobile and Pensacola bays, was thickly forested, and sawmills were often the first organized commercial operations up and running in promising hamlets.

Cedar thrived in the same lime-rich soil prized for cotton. By association, a towering stand of cedar trees was a promising advertisement for plantation land. As forests became plantations in Alabama and across the old Southwest, cedar trees were felled to make way for cotton plants by the same enslaved workers who were forced to work in the fields. Some planters turned their red cedar into plantation houses; others lashed the logs together into rafts, loaded their cotton on top, and floated the whole package downriver to Mobile, where wholesalers would send the bales and the logs on to markets on both sides of the Atlantic.

In 1839, William Munroe bought 20 tons of cedar from a New York merchant, assuming that the logs had come from Mississippi. Twenty tons was a mountain of wood, enough to make well over a million pencils, by Munroe’s reckoning—but even this was only a little more than a year’s supply. Given how much cedar he used, it’s telling that Munroe assumed rather than knew the origins of this most critical material. Perhaps the wood had come from Mississippi. More likely, Munroe had bought it from a commission merchant who had shipped it out of New Orleans without any special indication of its origin. At any rate, the expansion of the United States around the Gulf of Mexico simplified the cedar trade in the 1840s—the most important decade for Thoreau pencils and for Henry Thoreau himself.

“Every boy and girl that reads the Magazine has whittled a lead pencil.” That sentence, from an 1850 issue of Robert Merry’s Museum, a children’s periodical published in Boston, tells the story of a small revolution. When Thoreau, fresh out of Harvard, taught school in the fall of 1837, writing lessons still involved ink wells and goose quills that often survived for only a page or two before cracking and bleeding dark ink everywhere. After Thoreau quit his classroom—facing the prospect of the pencil factory—he wrote to friends teaching elsewhere to ask whether they knew of any schools with “hands to guide” and “pens to mend.” Yet not much more than a decade later, pencils were universal, at least among students whose parents could afford Robert Merry’s Museum.

The increasing availability of pencils coincided with a shift in the cedar trade that the magazine thought would make for a good story: “Do you know where the fragrant cedar comes from of which they are made?” The answer was meant to surprise. “From Florida. Yes, most of that used in this State”—Massachusetts—“comes from Florida; and they tell me the Indians prepare a great deal of it for the market.

Some immense trunks they find lying on the ground, with the sapwood all decayed. These are the round logs we see on the wharves. If you notice the style in which the timber is hewed, you will not doubt about the savages having a hand in it. Some of it looks as unfinished as though a broad-axe had been thrown at it! Or at best struck with but one hand, and that trembling from the effects of ‘fire water!’ It is very evident from these logs that the young ‘Osceolas’ abjure the square and compass of the ‘pale faces.’

Robert Merry’s Museum was right and wrong (and racist). By 1850, most pencil cedar was coming from Florida, and dead trees did make good pencils, but Seminole Indians weren’t the ones harvesting them.

In Florida, the cedar trade was tied up not only with cotton and slavery but also with war. After President James Monroe made Florida a territory in 1821, Andrew Jackson led the territorial government, charged with opening up roads and mail routes. Beginning in 1835, Florida’s settlers were volunteering to fight in the Second Seminole War, which would devastate the Indigenous population. When Florida was finally admitted as a state in 1845, most of its counties along the Gulf Coast consisted of small farmed tracts rather than expansive plantations. Slaveowners there raised livestock; planted cotton and food crops, including corn; and worked alongside the people they enslaved.

Well into the 19th century, the isolation and comparatively sparse population of the Gulf Coast made it fertile ground for timber thieves, usually sponsored by—and selling to—European naval powers. In 1822, a federal law was passed to deter and punish thefts, and boats were sent to patrol the coast. In 1826, the U.S. Navy built a permanent station in Pensacola, largely using slave labor. By 1834, 25 sawmills were operating around Pensacola, and local boosters were determined to make their town into another Mobile. Florida pine was tapped for tar and turpentine and fashioned into all manner of products in growing cities in the South, the Caribbean, and eventually the northern states, too. Cypress and live oak were highly valued for construction and shipbuilding—famously, “Old Ironsides” had been built from Florida live oak. But red cedar was the only wood suited for pencils, and in the 19th century, Florida had the world’s best cedar stands, which grew from “hammocks” of accreted soil slightly elevated above the swampy plains.

It’s hard to know the extent of enslaved workers’ involvement in the production of any given lot of Florida cedar. Work in the forests varied. Especially after the riverbanks were cleared, loggers camped deep in cedar hammocks for months at a time. Cutting the trees and dragging them to navigable water was, to say the least, difficult. The cedar logs on the wharves of Boston appeared rough and “primitive” because the camps where they had been cut were exactly that. Often, enslaved workers on nearby plantations were hired out to the logging camps, which also recruited wage laborers from the North. By 1860, Florida had 87 lumber mills, some small, with water-powered saws connected to plantations, and others large, steam-powered complexes that were as integrated and hierarchical as any industrial operation at the time. Especially in the steam-powered sawmills built after 1830, much of the workforce was enslaved, including cooks for the men who lived onsite.

One of antebellum Florida’s largest mill complexes was owned by William L. Criglar and his partner George Bachelder. The latter was from Danvers, Massachusetts, and had gone south as a young man to work on the Pontchartrain Railroad. After several years in New Orleans, he moved to Cedar Grove, Florida, east of Pensacola. Not long after, he and Criglar built a lumber mill and yard in nearby Milton and grew it into an industrialized operation with 99 saws worked by nearly 200 enslaved people. Bachelder and Criglar also owned more than 5,000 acres of timberland in Florida, plus lumber yards in New Orleans, Mobile, and Pensacola. From there they shipped wood to buyers from Boston to Rio.

The trade in Florida pencil cedar reached around the world. At the start of the 1850s, Eberhard Faber, heir to a German pencil-making family in business since 1761, began to buy up vast swaths of Florida’s Gulf Coast. His purchases included the richest cedar stand in North America, known as the Gulf Hammock, stretching from the mouth of the Suwanee River south past the Withlacoochee, including the Cedar Keys, a group of limestone islands two miles out in the Gulf. During the Second Seminole War, the islands had been developed as a military installation, with a prison camp for Indians awaiting removal west. After the war ended in 1842, there were plans to turn the outpost into a depot for the cotton expected to be raised along the Suwanee River. Instead the main crop was cedar.

While his lumber crews were working in the Gulf Hammock, Faber set up a sawmill and later a company town on one of the Cedar Keys, turning out uniform slats for efficient shipping to Faber pencil factories on both sides of the Atlantic. In the second half of the 19th century, Cedar Key became what Concord had been in the first: the pencil capital of the nation.

The leading pencil makers in the United States and Europe came to rely on Florida cedar. But could it be that J. Thoreau & Son had a different source? After all, the Thoreaus were “Concord’s first family of antislavery activists,” as Robert A. Gross puts it. And their commitment to antislavery politics had grown along the same timeline as Henry’s involvement in the pencil business.

Thoreau’s pioneering work on kiln-fired leads in the fall of 1837 coincided with the visit of abolitionists Angelina and Sarah Grimke to Concord. Two months later, Henry’s mother, Cynthia, and his older sister, Helen, helped organize the Concord Female Antislavery Society. The youngest member of the Thoreau family, Sophia, joined soon after. These commitments carried over to the Thoreau household, where Cynthia refused to have sugar on her table. Helen quit the Unitarian Church because it permitted slaveholders to preach.

By contrast, Henry tended to hang back from public politics until at least the mid-1840s, and John Thoreau was probably the least politically active member of the family. He was a Whig, and his politics were oriented toward economic development, though not at any cost. In 1840, the whole Thoreau family, John Jr. and Henry included, signed a petition opposing Florida’s admission to the union as a slave state.

Commodity-based complicity posed a tricky question in New England and transatlantic abolitionist circles alike. Since the beginning of the antislavery movement in England in the late 18th century, Quakers especially had boycotted slave-produced commodities, applying strict religious notions of purity to everyday economic life. At the same time, other factions of the abolitionist movement, even deeply committed and radical ones, downplayed and dismissed the importance of consumer activism. William Lloyd Garrison, who reckoned slavery a moral issue rather than an economic one, boastfully described going home after antislavery meetings and eating slave-produced sugar. Nonetheless, through the 1850s, women and Black Americans, including former slaves, continued to argue for the potential influence of boycotts. Yet even those who agreed often found the standard of “free produce” too difficult and expensive to uphold with any consistency. Slavery was implicated in too many things to be completely avoided.

But what about locally sourced substitutes—maple sugar instead of sugar cane, Massachusetts cedar instead of Florida cedar? When he was just starting out, William Munroe had managed to make a few decent pencils from cedar he found in the Middlesex hills. Henry Thoreau knew those woods better than anyone. At least one old woodsman in Concord, a town with plenty of them, said that Thoreau “was the best man he had ever known in the woods.”

Thoreau knew the Maine woods, too. He had a cousin, George Thatcher, in the lumber business in Bangor, where hundreds of sawmills were frantically transforming the state’s forests into stacks of lumber. Thoreau’s only extended absence from Walden between 1845 and 1847 was a trip he made to Mount Katahdin with Thatcher at the end of the summer of 1846, when he was awed by the scope of the operations he witnessed: “the arrowy Maine forest … sacrificed—soaked bleached—shaved—& slit” into “board, clapboards, laths, and shingles.” When he stopped at a store for supplies, Thoreau noticed local pencils for sale: by his standards, “bungling.”

Back at Walden, Thoreau heard the train pass and knew well what it was carrying: “Here goes lumber from the Maine woods … pine, spruce, cedar—first, second, third, and fourth qualities.” It was almost certainly white cedar. But putting aside for a moment the environmental obstacles to finding “first quality” red cedar in Maine, if there was a source of pencil cedar there, harvested without slave labor, Henry Thoreau was more likely to know about it than anyone else in the world.

If the Thoreaus did have a private source, they didn’t tell anyone about it, not even their employees. On its own, this would have been perfectly in character. Horace Hosmer, one of John Thoreau’s few employees in the pencil factory and a longtime friend of the family, called his boss the most secretive man he had ever met. John strictly avoided writing anything down, and Henry seems to have kept to the same policy, hardly mentioning pencils in his otherwise exquisitely detailed journals. As a result, virtually no archival evidence from the Thoreau pencil factory survives. John worked like “a monk in his cell,” refusing to “impart his knowledge or expand his business” much beyond his own household. To Hosmer, who made pencils for three decades himself, this seemed a significant loss, for John Thoreau’s knowledge and pencils were both of a rare quality.

By contrast, Hosmer had a keen eye for opportunity and loved to talk about it. With the onset of the Civil War, shipments of Florida cedar to northern pencil manufacturers were halted. The next year, Confederate troops abandoned the area around Pensacola, burning sawmills and lumberyards as they went, to prevent their seizure. With no new supply of red cedar, pencil manufacturers’ stocks dwindled quickly, even as demand for their product increased: soldiers carried pencils into the field to jot notes, record impressions, and write letters in unprecedented volume, spurred on by the recent invention of the envelope. As a result, the price of red cedar “was enormously high,” as Hosmer put it. Anyone who could get it, or even a passable substitute, was guaranteed a jackpot. Pencil makers in Europe and the United States alike scouted forests around the world.

Hosmer’s idea was Maine. He got a tip from a “Maine man” that he might find red cedar of a “superior quality” in Oxford County, in the foothills between the coast and the mountains. Hosmer made an exploratory trip in June 1862, a month after Henry Thoreau died of tuberculosis. After trawling the woods near the hamlets of Hiram and Porter, Hosmer seems to have returned to Concord empty-handed, for he later wrote that during the war, cedar simply “could not be obtained.” Maybe there was high-quality red cedar in Maine. Maybe “the Maine man” who had helped Hosmer was Henry Thoreau’s cousin George. Maybe Hosmer did find trees where the tipster had pointed. But even in this best-case scenario, the wood still wasn’t plentiful enough, or good enough, to make pencils on any significant scale.

The question of why Thoreau went to Walden has never been answered definitively. To write is the most familiar and compelling answer, and perfectly true as far as it goes. But for Thoreau, writing also meant something more: getting away from the pencil factory.

When Henry ended up scraping dust and chipping wood with his father after graduating from Harvard, he could envision even more clearly the life he really wanted. In the very first entry in a journal that eventually grew to roughly 7,000 pages and two million words, he wished for a “garret” where no pencil making would impinge: where the “spiders must not be disturbed, nor the floor swept, nor the lumber arranged.” Even as he worked diligently in the pencil factory, refining innovations crucial to his family’s livelihood, he was also eager to break free.

By 1845, after completing his work on the graphite grinder that would bring Thoreau pencils new renown, Henry was ready to write a book—an account of a boat trip he had taken with his late and beloved brother, John, a sort of memorial, which became A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. That spring, Thoreau built his house at Walden Pond on land Ralph Waldo Emerson had bought on a whim. Emerson could afford it in part because he received a reliable annual income from the estate of his late and beloved first wife, Ellen Tucker. As Emerson knew, Ellen’s father, Beza Tucker, had been a wealthy Boston merchant dealing in West Indies goods, meaning slave-produced commodities. According to Robert Richardson, who did not mention these connections to slavery in his biography, Emerson: The Mind on Fire, Beza Tucker also owned a rope factory in Boston. Given the orientation of his business toward the Caribbean, it’s likely that the rope he made was used to rig the ships carrying the goods he traded—and to bind the enslaved people compelled to produce them. This was Emerson’s income. Writing in his journal on July 6, 1845, his third day living on Emerson’s land at Walden, Thoreau described his move as a “self-emancipation in the West Indies of a man’s thinking.”

Keeping his own house seems to have emboldened Thoreau politically. He began to fashion a public persona, one “that could stand up to all the scrutiny and defend his private self from the glare of publicity” he now attracted, as biographer Walls describes. The character he developed was the town scold, “keeper of the public’s conscience.” His “every act was a sermon, and his every encounter—even a casual meeting on the road—was a challenge to explain, to justify, to proselytize.”

Thoreau’s “iron-pokerishness,” as Nathaniel Hawthorne put it, takes on a new facet with pencils and cedar in mind. Why would Thoreau’s neighbors in Concord, a town full of pencil makers, have tolerated a hectoring performance from someone standing on a pile of slave-produced lumber?

Yet that question risks getting the problem backward. His neighbors didn’t bring it up, and he didn’t make a point of it, because the cedar wasn’t hidden, least of all by Thoreau himself.

Late on a sunny afternoon in July 1846, Henry Thoreau left his house by Walden Pond and walked two miles to the cobbler’s in the center of Concord. On the way, Thoreau happened to run into his hunting partner Sam Staples, the town constable and tax collector. As he often had, Staples asked Thoreau about his overdue poll taxes—four years’ worth, about six dollars. Warning that jail was next, Staples offered to pay the tax bill on Thoreau’s behalf. When Thoreau declined the offer, Staples responded, “Well come along,” and Thoreau did.

Neither Thoreau’s tax refusal nor his imprisonment was directly related to the Mexican-American War, which had begun a few months earlier. Thoreau had stopped paying taxes years before, and the timing of his arrest owed more to Staples’s laziness than anything else. Yet when Thoreau retrospectively described his arrest as an act of protest, he focused the story on the expansion of slavery around the Gulf of Mexico—through cedar country. “I love mankind,” he wrote in his journal shortly after his night in jail. “I hate the institutions of their forefathers.”

Thoreau wrote the text that became “Civil Disobedience” as a two-part speech, which he delivered in Concord in January and February 1848. When the speech was solicited for publication the next year, he had little time to revise it. The original audience for one of the most influential essays in global history was local. Thoreau’s listeners already knew his story, as well as his family’s politics and business. When he asserted that “I am not responsible for the successful working of the machinery of society,” for “I am not the son of the engineer,” they knew exactly whose son he was.

John Thoreau makes a brief but noteworthy appearance in his son’s essay, which detours through a story that highlights their differences. “Some years ago,” Henry writes, “the State met me on behalf of the Church, and commanded me to pay a certain sum toward the support of a clergyman whose preaching my father attended, but never I myself. ‘Pay,’ it said, ‘or be locked up in the jail.’ I declined to pay.” The anecdote has no known basis in fact. Robert A. Gross doubts whether it happened at all, for church taxes had been discontinued by the time Henry was old enough to pay, and jail was no penalty for unsubscribing from a congregation’s rolls. Told in the broad strokes of a parable, the story helps to frame Thoreau’s tax refusal as a matter of character and conscious principle rather than feckless impulse or chronic delinquency.

But John Thoreau’s presence in the story also marks his son’s essay as a protest against him. Henry goes out of his way to cast his father—the only character named in the essay who would have been personally known to the audience—on the wrong side of the question. John represents his son’s presumptive guilt by association. Was there an analogy between John Thoreau and his church and John Thoreau and his state? Did John “attend” the services of the government that made war in Mexico on behalf of slaveholders? Henry seems to have been saying that despite appearances and assumptions, J. Thoreau and son didn’t worship the same creed, or subscribe to the same institutions.

“Civil Disobedience” is an inquiry into the problem of complicity and what to do about it. Thoreau pieced together an answer through metaphors drawn from his family business. “If I have unjustly wrested a plank from a drowning man,” writes Thoreau, “I must restore it to him though I drown myself.” His foundational metaphor for justice was lumber, which of course meant slavery. “Let your life be a counter-friction to stop the machine,” the inventor of sophisticated graphite grinders advised his audience.

But that was asking a lot, and Thoreau knew how many people were reluctant to take such a stand, with their livelihoods at stake. He was among them. “I do not wish to … set myself up as better than my neighbors,” he explained. “What I have to do is to see, at any rate, that I do not lend myself to the wrong which I condemn.”

After Thoreau was released from Concord jail—to his chagrin, someone, probably his aunt, paid the tax on his behalf—he went back to Walden Pond and kept writing. By the time he left his house by the pond in September 1847 and moved back in with his parents, he had finished a draft of the book about his brother. The problem was that no one wanted to publish it. Determined, Thoreau kept reworking the manuscript for a year and a half more. In 1849, the same year that “Civil Disobedience” was published, Thoreau paid around $290—roughly equivalent to a year’s wages—to print 1,000 copies of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. He raised some of the money by making and selling extra pencils. Perhaps he did not “lend himself” to the slavery he condemned, but he did borrow from it.

Even as he was working on “Civil Disobedience,” Thoreau was eagerly looking for an alternative to the pencil factory, something better to do to contribute to his family’s livelihood. In the spring of 1849, he took his first surveying job, laying out the road the town planned to build in front of the family home—so much the better for getting cedar in and pencils out. Yet his work as a surveyor often left him wracked with guilt over the changes to the land that he was enabling, speeding forests on their way to the sawmills.

And then, at the end of 1849, the year “Civil Disobedience” was published, the Thoreaus got an opportunity to avoid lumber altogether. They began selling their graphite, precisely ground using the technology Henry had invented, for use in electrotyping instead. Over the next few years, the Thoreaus wound down operations in the pencil factory, just as the German firm Eberhard Faber was claiming a larger share of the U.S. pencil market and buying up Florida cedar hammocks. By the time Thoreau spoke on “Slavery in Massachusetts” in Framingham on July 4, 1854, J. Thoreau & Son had been out of the pencil business for about a year. Of course, the advantages the Thoreaus had drawn from that business—the houses, the educations, the books, the money, the time, the freedom—remained theirs, and even gained new currency, the family having shed its most direct associations with the systems and institutions Henry now decried even more loudly.

“The majority of the men of the North, and of the South and East and West, are not men of principle,” Thoreau argued in “Slavery in Massachusetts.” Instead, he went on, “it is the mismanagement of wood and iron and stone and gold which concerns them.” “Thoreau’s address,” writes Walls, “propelled him into the most militant ranks of the radical abolitionists.” The press covered it avidly, alongside publicity notices and advance excerpts of Walden, set to be published a month later. Thoreau, Walls writes, was pitched as “the ‘Massachusetts Hermit’ who had stepped boldly into the glare of radical abolitionism.”

Thoreau is arguably as famous for his hypocrisy as for his writing. Even some of his most sympathetic readers and fans delight in charging him with ethics violations against himself, as if his point in moving to Walden Pond was to take a stand against going home for dinner. Yet this overly literal practice of moral bookkeeping says more about our notions of right and wrong than about Thoreau’s.

In the past two decades, historians have traced an expanding web of once-obscured connections that remap the history and legacies of slavery, and in the process reframed the stories of individuals and institutions not conventionally understood in that light. But it’s possible that such a method itself obscures a larger point.

In antebellum Concord, it wasn’t possible to “discover” an individual’s, a family’s, or an institution’s connections to slavery, which were already known to be everywhere. It wasn’t necessary for Thoreau to call attention to the slave-produced red cedar his family made into pencils, for there was no presumption that it did not exist. There was no assumption that the financial beneficiaries of slavery could simply pay what they owed to the victims, call it square, and carry on. Slavery was the entire plank, the whole pile of lumber.

The real question was the one that led Thoreau to Walden Pond, and then to jail, and kept him up at night: What to do about it now? His answer changed over time. In the fall of 1859, on the night he heard of John Brown’s assault on Harper’s Ferry, Thoreau put a pencil and piece of paper underneath his pillow, as if to ensure that he wouldn’t be able to sleep. When he woke up in the middle of the night, he picked up the pencil and wrote:

Our foes are in our midst and all about us. There is hardly a house but is divided against itself, for our foe is the all but universal woodenness of both head and heart, the want of vitality in man, which is the effect of our vice; and hence are begotten fear, superstition, bigotry, persecution, and slavery of all kinds. … These men, in teaching us how to die, have at the same time taught us how to live.

In the end, Thoreau’s pencils point to this other Thoreau—conflicted, frustrated, opportunistic, guilty, but also angry, even fearsome, and determined, for he understood that the world that could be redeemed by Walden Pond alone never existed.