Botticelli’s Secret: The Lost Drawings and the Rediscovery of the Renaissance by Joseph Luzzi; W. W. Norton, 352 pp., $28.95

The first complete English translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy appeared in 1802, and over the past two centuries, new versions have proliferated beyond count, like Beatles covers or Sherlock Holmes movies. A diverting literary parlor game is to imagine the best translations that weren’t written.

T. S. Eliot would have produced something soul bending; Anthony Burgess suggested that the world lost a great Inferno when Wilfred Owen died. A similar game could be played with Divine Comedy illustrations, of which Gustave Doré and William Blake have provided the best known that do exist. Goya and R. Crumb would have produced the best that don’t.

Somewhere between existence and nonexistence is the version of Dante by Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445–1510), unquestionably the greatest artist to take up the challenge. He died with his series of 100 drawings, one for each canto, unfinished. Each drawing is scratched into sheepskin roughly the size of a broadsheet newspaper. Botticelli went over the scratchings in pen and left most uncolored. The ink has faded to a light brown. The drawings are wan and at times doodlelike, as if they were studies for the greatest graphic novel ever conceived.

Botticelli’s Dante cycle is the primary subject of Joseph Luzzi’s new book, Botticelli’s Secret. After his death, Botticelli was forgotten, as were so many artists of the Italian Renaissance, and he remained so until the 19th century, when English essayist and critic Walter Pater and a handful of other Anglo-Americans revived him (and started translating Dante). Among the observations made by Pater and others was that Botticelli, the master of such pagan scenes as The Birth of Venus and Primavera, was temperamentally unsuited to the depths and despair of a journey to hell and back. A certain vision of Italian womanhood belongs to Botticelli: Venus, her strawberry locks blown by the west wind, stares off-canvas vacantly. The master of this untroubled look is not, one would predict, the natural illustrator of the most troubled poet of them all.

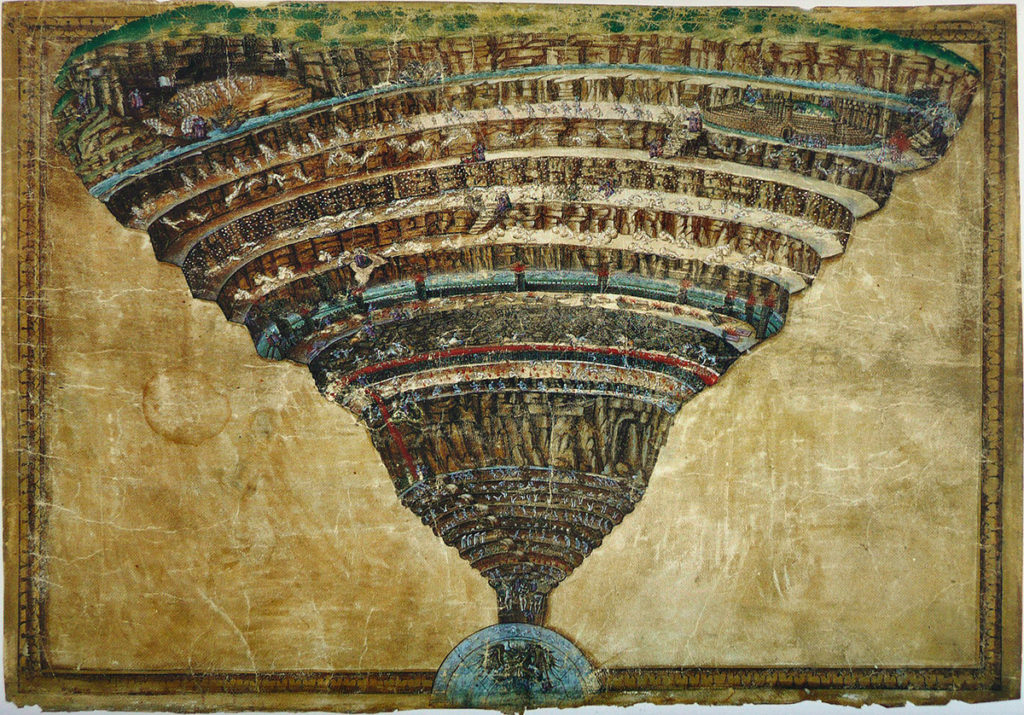

But one would be wrong. The most elaborate drawing, The Map of Hell, resides in the Vatican Library. It shows the Inferno as a large funnel, with the center of Earth in the middle and each layer uncomfortably overcrowded with the dead. Other scenes show Virgil and Dante on their rocky descent, peeking over the outcroppings at the pale forms of the damned. The most elaborate portrait in the cycle is that of Satan, winged and clawed and hairy.

For Botticelli’s troubles he was mocked, or at least not rewarded, in his own time. Giorgio Vasari, the source of so much gossip about Italian artists, said Botticelli wasted his time on Dante. The artist died poor, despite having run one of Florence’s most celebrated workshops. Luzzi notes that for hundreds of years, the Primavera and Birth of Venus—now the subject of permanent traffic jams at Florence’s Uffizi Gallery—hung in the private dwellings of the Medicis and were “seen only by a hundred or so people.” Only in the 19th century, when the English began to discover Dante, did they discover Botticelli, more for his paintings than for his drawings, and elevate his works to their current positions just below Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s.

In Botticelli’s Secret, Luzzi, a professor of comparative literature at Bard College, combines a primer on Dante and his reception in Florence with a short biography of Botticelli and the story of the works’ posthumous physical and reputational journey. After a trip to Paris, the Dante cycle ends up in England and is finally recognized as priceless in 1882 by Friedrich Lippmann, director of the Royal Museum of Berlin. Lippmann consolidated all but the seven items in the Vatican, and save for a few adventures during the Third Reich and Cold War, the cycle has remained intact and properly curated ever since. Luzzi’s heroes are these 19th- and early-20th-century connoisseurs who recognized Botticelli’s genius amid the heaps of junk and treasure in Florence. Some saw more clearly than others; Lippmann, for example, knew that the Dante drawings were Botticelli’s own and bought them for Berlin before less farsighted Englishmen could preserve them for London.

The great mystery, less illuminated by Luzzi, is Botticelli himself. Other major artists of the Italian Renaissance lived dramatic lives, their stories replete with love affairs, fights, political plots, a papal commission here, an absolution there. In Botticelli’s case, the evidence suggests that he preferred to perfect the work rather than the life, which was dull indeed by the standards of his murderous, nympho peers. He maintained a workshop and paid his taxes. He avoided marriage and children and probably preferred men. Vasari’s distaste for Botticelli sometimes feels like sublimated resentment at the artist for not having supplied him with adequate biographical material.

Botticelli neither wrote nor said anything of particular interest, let alone produced notebooks like Leonardo, or poetry like Michelangelo. His silence in the record convinced some historians that he was illiterate, but Luzzi agrees with modern scholars that Botticelli was literate and intelligent, by the evidence that he “collaborated with many of Florence’s leading minds” and showed cultural mastery through allusion and interpretation. The evidence Luzzi adduces is hard to assess. The drawings themselves show attention to The Divine Comedy, but as Luzzi notes, even garbage men of Botticelli’s time could quote Dante. The drawings themselves are deeply perplexing, in part because of the puzzle of their origin, from the hand of an artist so inventive in the depiction of a pagan paradiso terrestre in his more famous work.

Luzzi has set a frustrating, not to say impossible, task for himself. This is not a book about Dante, but without a lot of discussion of Dante, it would be impossible to understand why the poet would inspire such devotion, or what we should read into the allusions in Botticelli’s cycle. The drawings themselves are so numerous and subtle that one wishes for close discussion of individual lines, expressions, and gestures. There are so many, and the book’s plates are so small and few, that a more focused discussion will have to wait for another time.

Luzzi understands this frustration. The book’s titular secret is revealed to the author on a trip to the Vatican, where he is unexpectedly allowed a 15-minute audience with The Map of Hell by an indulgent museum director. There Luzzi sees “all the mind-boggling intricacies and textures coalesced into a seamless whole”—an understanding of Botticelli’s Dante untranslatable out of the presence of the art itself. Luzzi is transformed by the secret and writes that he has seen “heaven’s own language.” I don’t begrudge him his good luck, but as a reader, I am left feeling equal parts envious and unsatisfied—forever excluded from Botticelli’s secret but now aware, as I would not have been before reading this book, of just how much I am missing—as Luzzi might want me to be.