Triumph of the Underdog

A new biography offers a sympathetic portrait of Lincoln’s greatest general

Grant by Ron Chernow; Penguin Press; 1,104 pp.; $40

Americans tend to stereotype their most notable presidents. Contemporary reporting and early biographies often lock in impressions, especially of failings, that persist for decades. Inevitably, though, a first-rate biographer challenges the conventional wisdom and redefines the man—so far, only men—in light of new information and a longer perspective. Thus some of our most eminent historians have given us fresh appraisals that have changed our understanding. Writers who have done so in single-volume biographies include David Donald (Lincoln), David McCullough (John Adams and Truman), Robert Dallek (Kennedy and, soon, Franklin Roosevelt), and Ron Chernow (Washington).

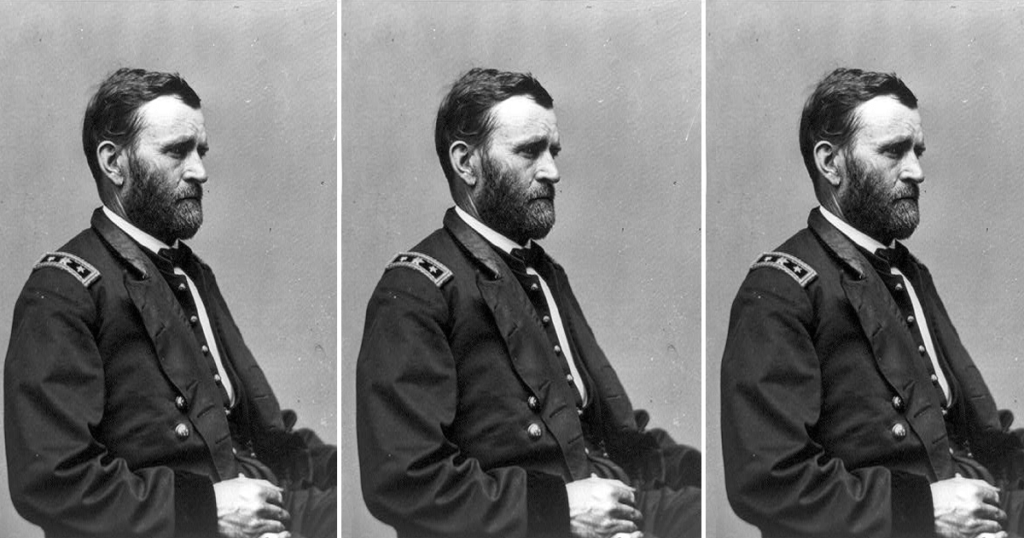

Now Chernow has done it again with a landmark work on the much-maligned Ulysses S. Grant. Like his earlier biographies of Washington and Alexander Hamilton, it is deeply researched, eminently balanced, and fair. No longer do we have the talented-but-flawed general who drank his way to victory in the Civil War and the hapless president who struggled through two scandal-plagued terms. Instead, Chernow gives us a military genius who understood the full scope of the war and pursued a winning strategy, and a sometimes inept president who, though unschooled in politics, made his highest priority the protection of the lives and rights of freed slaves.

“Dismissed as a philistine, a boor, a drunk, and an incompetent,” Chernow writes, “Grant has been subjected to pernicious stereotypes that grossly impede our understanding of the man. … In fact, Grant was a sensitive, complex, and misunderstood man with a shrewd mind, a wry wit, a rich fund of anecdotes, wide knowledge, and penetrating insights. … At the same time, Grant could be surprisingly naïve and artless in business and politics.” As for his reputation as a drunk, Chernow maintains that, with help from his wife Julia and his staff, Grant’s drinking was “measured” during the war, and eventually diminished to nothing.

Trained at West Point and seasoned in the Mexican War, Grant was saved from a chronically unsuccessful civilian life by the the Civil War, which drew on his immense military talents. Chernow rightly focuses on these years, which were decisive in determining not only Grant’s personal destiny but that of the nation. Chernow is particularly insightful in showing how critical the Lincoln-Grant relationship was to winning the war. The two men were perfectly aligned: Lincoln desperately needed a general who would fight; Grant embraced ending slavery, long a personal conviction, as essential to the northern cause.

After Grant won brilliant victories in the West, Lincoln called him east in 1864 to assume command of all Union armies as lieutenant general and to personally take on the tenacious but elusive Robert E. Lee. Lincoln had been plagued by generals who possessed neither strategic vision nor the will to fight, and seeing in Grant a man with neither of those deficiencies, chose to overlook his new commander’s reputation for drinking. He gave him his unequivocal backing and promised to leave him alone. “The particulars of your plans I neither know or seek to know,” the president told his general, and he kept his promise.

In the spring of 1864, Grant set off with the Army of the Potomac, determined to bring Lee’s army into the open where the North’s greater numbers could prevail. But the savvy Lee wouldn’t bite. In a four-week campaign “distinguished by a savagery unseen in the war,” Chernow writes, Grant threw wave after wave of Union soldiers against entrenched Confederates at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and finally Cold Harbor, suffering horrific casualties without achieving the decisive win that would end the war. Critics began calling Grant a “butcher,” a charge that Chernow challenges: Grant, he writes, “had much the harder task: he had to whittle down the Confederate army and smash it irrevocably, whereas Lee needed only to inflict massive pain on the northern army and stay alive to fight another day.”

Instead, Chernow sees Grant as a “strategic genius” who masterminded the movement of Union armies East and West. He eschewed credit for the important victories of Generals Sherman, Sheridan, and Thomas, but all were under his command. “Grant’s strategy embraced a continent;” Sherman wrote. “Lee’s a small State.”

From besieged Petersburg, Grant pursued Lee’s weakened army until its surrender at Appomattox Court House in April 1865. In a historic act of generosity, he paroled all southern soldiers, making them immune from prosecution for treason. This effort to begin the process of reconciliation, according to Chernow, represented “a fleeting, if in many ways doomed, hope. … [S]urrendering was one thing … acceptance of postwar African American citizenship and voting rights would be quite another.”

Grant’s embrace of Radical Reconstruction combined with his war heroism to earn him the presidency in 1868. “He did not exactly want the presidential job,” Chernow writes, “but neither did he exactly not want it.” In his political life, there had always been an “illusion of passivity, the sense of a massive wave lifting him to the next plateau.” Once in office, however, he found himself at sea politically. Believing he could rely on his military experience in selecting capable subordinates, he found out too late that he couldn’t. Without proper staff work, his decision-making became “maddeningly opaque,” and resulted in many disastrous appointments. But after a lifetime of sympathy for the underdog, he courageously appointed a number of Jews, Indians, and African Americans to important federal positions.

His overall priority as president was to support vigorously the policy of Reconstruction. When many white southerners tried to deny freed slaves their rights, he unhesitatingly sent in federal troops to enforce the law. When the newly organized Ku Klux Klan launched what Chernow calls “the worst outbreak of domestic terrorism in American history,” Grant suspended habeas corpus, declared martial law and fought for legislation aimed at the Klan. He was “sure-footed,” Chernow writes, “when it came to protecting freed people. … He knew that the Klan threatened to unravel everything he and Lincoln and Union soldiers had accomplished at great cost in blood and treasure.” But Grant’s proudest legacy as president was undoubtedly his pursuit of justice for freed slaves—a commitment that laid the groundwork for the great civil rights movement nearly a century later. America would not see as determined or consequential a civil rights leader in the White House until Lyndon B. Johnson.

The end of Grant’s presidency found him without a home, money, or plans. He and Julia took a two-year trip around the world, during which he was feted as a hero in capitals from Europe to Asia. Settling in New York, he was snared by a Wall Street scam that left him financially bereft. Having nothing to leave Julia, he agreed to write several articles and eventually a memoir of his wartime service. His friend Mark Twain, a former Confederate soldier, realized what a hit his work would be and arranged a highly remunerative book deal that assured Julia’s security. Grant devoted himself to the project, correcting the public record where necessary and otherwise telling the story through his own experiences. By now, he was dying of a painful cancer in his throat, but he persisted, showing the same courage he had displayed in the war; he finished his manuscript only days before his death. The memoir sold 300,000 copies, a huge number for the time. It also came to be seen as a great literary achievement, perhaps the greatest memoir of any American president.

Just as that memoir will likely persist as a definitive work of its kind, so too will Chernow’s book—a monumental and gripping work in every respect, which even at nearly 1,000 pages, is not a sentence too long.

With this work, Chernow impressively examines Grant’s sensitivities and complexities and helps us to better understand an underappreciated man and underrated president who served his country extraordinarily well. The simultaneous arrival of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant on the scene of America’s greatest crisis, during which they fought together to save the Union and free its enslaved peoples, is one of the greatest blessings of the much-blessed American experience.