Under a Spell Everlasting

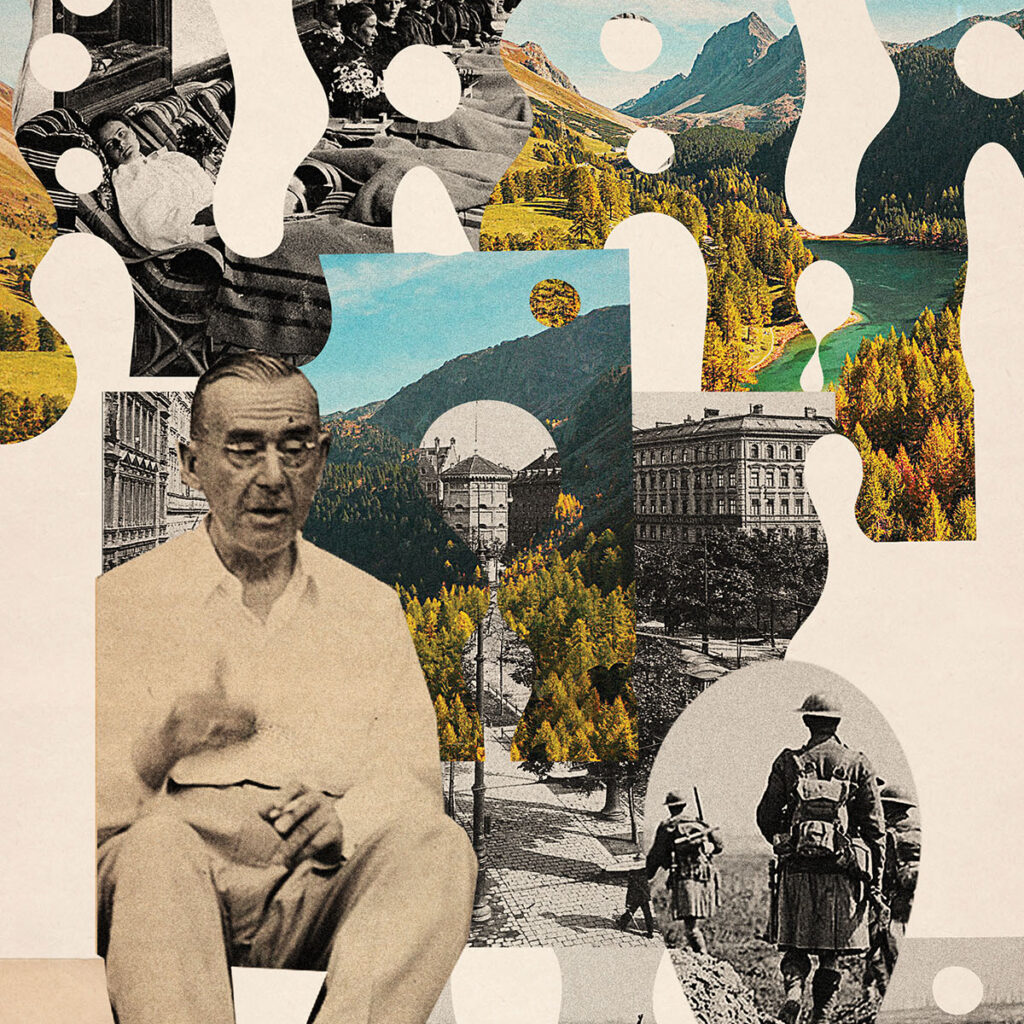

Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain, published a century ago, tells of a world unable to free itself from the cataclysm of war

There is only one way to reach the Berghotel Schatzalp, in Davos-Platz in the Swiss canton of Graubünden. You must switch trains at Landquart, a small municipality in the Alps, where you stand on an open-air platform in the wind without even the consolation of a view. From there, the train follows the Landquart River, leaving behind the villages and castles nestled in the valley, before beginning to ascend 3,907 feet up into the mountains, squeezing between sheets of rock and forest. Looking out the window, all you see are trees, dense green larches, rough pines, ridges bristling with firs. And then, another 2,000 feet of elevation, as you pass through a series of covered horseshoe tunnels before breaking through the tree line and descending into the high valley of Davos-Platz. Stepping off the train onto the station platform, you must now find your way to the funicular, which ascends another 1,000 feet in four minutes, finally arriving at the summit where the Schatzalp sits. This much has not changed since Thomas Mann published The Magic Mountain 100 years ago.

I have arrived in Davos to explore the world of Mann’s novel, which I discovered during a period of convalescence after writing my first novel. Burnout might sound romantic, in the contemporary sense of the word, but the reality of such deep exhaustion is that I’d severed the relationship between my mind and body and needed to find a way to heal myself. Unable to read, write, or look at a computer screen, I was able to move through the world, but was no longer really in it. I had gone to spend the evening with a friend in Brooklyn, intending to have dinner and see a concert, and ended up staying with her for two months. In a moment of desperation, fearing I would never be able to write again, that I had somehow broken myself irreparably, I started listening to The Magic Mountain on my phone, lying in a stupor on her bed, watching the sun rise and fall with no sense of days passing, drifting in and out of sleep. By the time Hans Castorp was dead, I had returned to the world of the living, but I was no longer my old self.

That was October 2022. And now, a little more than a year later, I have come to Davos because I want to see what Mann saw, because I want to pay homage to the work that helped me return to life. And because my intuition tells me Mann got something right that might help us think about our world today: It is not the legacy of World War II, as many scholars argue, that shapes our political reality, but the spell cast by World War I, a spell from which so many things have begun, and from which we have yet to awaken.

The Magic Mountain tells the story of Hans Castorp, an ordinary young man who goes to visit his cousin Joachim at the International Sanatorium Berghof in Davos-Platz for three weeks and ends up staying for seven years. The novel is a meditation on love and death, sickness and health, time and modernity. One cannot help but be charmed, or annoyed, by the cast of characters who play out the political and philosophical debates of the day. There is Leo Naphtha, the brilliant Jesuit communist of Jewish origin, and his nemesis, the Italian liberal-humanist Lodovico Settembrini. There is Dr. Behrens, the chief physician, who examines the inner workings of his patients’ bodies, and his counterpart, Dr. Krokowski, the resident psychoanalyst, who examines the inner workings of their minds. There is the hedonist Clavdia Chauchat and her larger-than-life lover Mynheer Peeperkorn. And there is Hans, who is desperately searching for himself amid the expectations of petit-bourgeois society, and his duty-bound, self-possessed cousin Joachim.

Critics have never quite agreed on what to do with The Magic Mountain. When it was published in November 1924, the medical profession received it as a satire of sanatorium life. Today, it is considered a modernist masterpiece but is seldom set next to James Joyce’s Ulysses. Buddenbrooks, which won Mann the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929, is often considered the stronger novel, a “classic work.” Perhaps the difficulty lies in The Magic Mountain’s mimetic form, which engages in a reproduction of reality through art—a mode of writing that has lost its potency in our age, in which reality is represented according to ideological demands. (György Lukács, the Hungarian Marxist philosopher and literary scholar on whom Mann based the character of Leo Naphtha, called the author the last great realist critic.) Some readers approach The Magic Mountain as a myth rife with symbolism, whereas others see it as a traditional bildungsroman, or coming-of-age novel. Most often it is read through a political lens, as a snapshot of bourgeois European culture before World War I, as a warning of the dangers of decadence, an omen of what is to come—a bildungsroman for a nation. They see it as a testament to Mann’s own political conversion to democracy in 1922. Mann himself called The Magic Mountain a Zeitroman (time-novel) and a “fairy-tale.” And he counseled that it must be read twice—a tall demand for a 700-page book.

Hans Castorp arrives in Davos-Platz in the middle of summer. I have arrived on December 22, in what feels like the middle of winter, to spend one week at the Waldhotel for Christmas Fest, and another at the Schatzalp to celebrate New Year’s. These are the two hotels, once sanatoriums, that inspired Mann’s work. The Waldhotel has arranged for a taxi to fetch me from the station, but the driver is late. After an hour or so of my standing in the snow, he arrives, apologizing profusely. A wine shipment needed to be picked up, and so I share a ride with several cases of the champagne that will be poured for guests later that evening.

The Waldhotel is not the kind of place you check into for one night. At reception, I am invited to sit down as my dinner reservations and spa appointments are confirmed. I have signed up for the Fest Program package, which includes a sledge ride in town the next day. I immediately feel at home in the hotel’s close quarters. There is a sense of community among the travelers who have chosen to spend their holidays here, rather than with family. Everyone greets one another with a smile. It is the smile of the leisure class removed from the familiar trappings of everyday life. Up here, on the mountain, there is nothing to do, nothing to worry about. All expectations are gone. Although many hotels are places where you might go to experience something, the Waldhotel is where you go to be relieved of the need to experience anything. Here, I am permitted the pleasure of a premature retirement from the world. And there is a great sense of relief in that.

That the Waldhotel used to be a sanatorium only adds to the romance of the atmosphere. Mann was inspired to write The Magic Mountain after visiting his wife, Katia Mann, at the Waldsanatorium in 1912. She had been diagnosed with a lung complaint and was sent to the mountain for treatment. Mann rented the villa below the sanatorium and visited her daily, taking walks up to the Schatzalp while he was finishing Death in Venice. (The Magic Mountain was initially conceived as a comedic sequel to that novella.) The Schatzalp provided the architectural details for the fictional Berghof sanitorium, but its interior was modeled after the Waldsanatorium. Upon Hans’s arrival at the Berghof, Joachim tells him: “Our sanatorium lies at a higher altitude than the village, as you can see. … The highest of the sanatoriums is Schatzalp, across the way, you can’t see it now. They have to transport the bodies down by bobsled in the winter, because the roads are impassable.” There is too much snow when I arrive to see the lights of the Schatzalp above.

In the 19th century, tuberculosis was the most common cause of death in Europe and North America. The sanatorium was devised to treat patients with tuberculosis in 1853 by a young German doctor, Hermann Brehmer. Brehmer argued that tuberculosis could be cured in its early stages with a strict regimen of fresh air, exercise, and good nutrition, which included the “beef-steak and porter” diet:

frequent supplies, in moderate quantities, of nourishing diet and wine; a glass of good Sherry or Madeira in the forenoon, with an egg, another glass of wine after dinner, fresh meat for dinner, some nourishing food for supper, such as sago, or boiled milk, according to the taste and digestive powers of the patient.

It also included morphine before bed to ensure a good night’s rest.

Up in my room, I find a basket of holiday treats and a note on my pillow reminding me to report at 6:45 p.m. sharp for a welcome cocktail in the lounge. Having a few hours to spare, I change into my bathing suit, robe, and slippers and go downstairs to the spa for a swim and a steam. Most residents have gone skiing or snowshoeing for the day, so I have the pool to myself. Unfortunately, I find a coughing German couple in the steam bath. I mumble Entschuldigung (excuse me) and make my retreat. I shower, dress, and follow the piano music to the lounge, where the bartender has made a fire.

Trays of champagne are passed around, and the director of the Waldhotel, Marietta Zürcher, is there, greeting guests. When I tell her why I have come, she seems amused. “I didn’t know Americans read Thomas Mann,” she says. This is not the last time I’ll hear this refrain during my time in Davos.

I am mostly surrounded by retired couples in their 60s enjoying a ski holiday. One couple invites me to sit with them near the fire. I practice my rusty German, and we discuss the quality of the snow and the skiing conditions before drifting for a moment into American politics—but nothing too serious. Mostly they want to know why a young American woman is spending her holidays in Davos alone.

Marietta invites those of us with a dinner reservation to make our way to the dining room. Inside, a partition separates the hotel guests from those who have only come for a few hours to dine. I am seated next to a window that affords a panoramic view, snow falling in the alpine night. A name card lets me know that this will be my table for the duration of my stay. A waiter brings me a wine list as I unfold my napkin. Tonight: porcini mushroom soup; fillet of arctic char with tarragon sauce on golden millet, with crispy kale and black salsify; and for dessert, a selection of local cheeses served with pear bread and figgy mustard. After dinner, I take a glass of sherry into the lounge and admire the bookshelves, which encase Mann’s printed works and critical editions, free for anyone to read at leisure. I pick up one of his journals and dust off the cover. As far as I can tell, it isn’t just Americans who aren’t reading Thomas Mann.

On September 1, 1914, Thomas Mann had been working on The Magic Mountain for nearly two years. Like many German artists and intellectuals of his day, Mann assumed that there was a line between the private life of an artist and the public world of politics. In Germany, at the time, there was a latent assumption that artists were not political. It was no secret that Mann was a patriot who remained loyal to his country, even when he knew Germany was going to lose the war. And when he wrote Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man in 1918, he asserted that at heart, Germans were not a political people. They were, in so many words, more concerned with their private affairs. But within a few years, his militancy softened, as he saw the direction in which blind nationalism was headed. It was the assassination of Walther Rathenau (the Weimar Republic’s foreign minister) by right-wing extremists in 1922 that shocked Mann out of his stupor and the comforts of his own bourgeois life. When he made his speech “On the German Republic,” he also shocked his friends and colleagues by declaring himself a democrat, publicly committing to the principles of the Weimar Republic. In the following year, he became one of the most outspoken critics of Hitler, sealing his fate. Targeted by the far right, he was forced into exile when the Nazis came to power in 1933, and he moved to Switzerland before settling in the United States.

Mann’s conversion is reflected in The Magic Mountain’s final chapter, which took shape after 1922. The book is divided between chapters that were written before and after the war, and before and after Rathenau’s assassination. In his collection of essays on Mann, Lukács wrote that it was the inwardness of romanticism that had previously blinded him. Mann had been more concerned with the life of the ordinary bourgeois man than the conditions of chauvinistic imperialism that allowed him to exist. Hans Castorp was only supposed to become a simple man, but then, instead of finding himself in the comforts of a corner office, he ends up blown to pieces on the battlefield of an imperialist war.

The next morning, I make my way to the dining room and find my table near the window. The hotel’s morning paper reports the day’s weather forecast: a high of minus one degree Celsius, with heavy snowfall in the evening. Inside the paper there is an à la carte egg menu, to supplement the offerings of a full breakfast buffet, and a copy of the evening’s dinner menu: beetroot mousse with green apple gel and goat cheese; horseradish foam on pumpernickel crumble; venison entrecôte with dark chocolate sauce, herb dumplings, red cabbage, oyster mushrooms, and spiced pears; and an ice-cream sundae for dessert.

After breakfast, before our sledge ride through town, Marietta takes me on a tour of the hotel. She leads me along a corridor to a gallery wall where the original blueprints for the sanatorium hang. Across from the blueprints, suspended in a narrow wood box, is a pneumothorax machine. This device was once used to treat tuberculosis patients by injecting nitrogen gas into the chest cavity. In The Magic Mountain, Joachim explains this surgical procedure to Hans: “When one lung has been badly ravaged, you see, but the other is healthy or relatively healthy, the infected one is relieved of its duties for a while, given a rest. Which means that they make an incision here, somewhere along the side here. … And then they let gas in, nitrogen.” Marietta unlocks the door to a room across the hall, which has been preserved. “This is what Katia Mann’s room would have looked like,” she says. There’s a washbasin, a single bed, and a small dresser. “Look,” Marietta says, “there is a thermometer.” I pick it up and twirl it between my fingers like a pencil, then place it back on the table beside its case. When the sanatorium was transformed into a hotel, Marietta tells me, many elements were kept the same, including the original glass door—which is often slammed in Mann’s novel—along with the wood floors, ceiling tiles, and light fixtures. “As you can tell,” she says, pointing to a glass lampshade in the dining room, “it is not modern for today.”

Reflecting on the writing of The Magic Mountain, Mann described how he had borrowed Richard Wagner’s use of the leitmotif, a short, recurring musical phrase. A leitmotif is like a spell that performs an incantation on the reader. You get lost in the repetition and ask yourself: Have I already read these passages? Certain words or turns of phrase prepare you to expect what’s coming. This authorial trick has the effect of causing you to lose track of time. Has it been one day, or nine? Has it been one year, or five?

Mann’s novel reminds us why the great poets and physicists dabbled in mysticism. In 1922, in the midst of his political conversion, Mann spent several months attending séances. The book’s original German title, Der Zauberberg, is translated as The Magic Mountain, but zauber in German incites more than a sense of magic; it is an ensorcelling. Berg means mountain, and the title gives the feeling that the mountain itself is casting a spell. The mountain is the magician, and its magic is the creation of a hermetic world.

At the Waldhotel, we too have lost track of time, between our trips to the sauna, afternoon naps, cocktail hours, and multicourse meals, seated next to the same dining companions night after night. No one ever asks when you are leaving. They only ask, When did you arrive? Up here, time does not proceed in a linear fashion. Wake, eat, sleep, wake, eat, sleep, many times in the course of one day. By Christmas, no one can finish their supper. Panna cotta with bresaola, asparagus, and brandy gel; pumpkin soup; fish with thyme sauce, rice, and sausage; roasted duck breast with honey-rosemary sauce; pommes Dauphine with cabbage; and apple strudel with milk glaze. The waiters implore us to at least try a bite of each course. The chefs know they have prepared too much. But after so many multicourse meals, so many days in a row, one finds it difficult to lift a fork. Abundance becomes a burden. What was an amusement becomes an obligation. So much rest, so much nourishment, so much snow. Up here, the only philosophy seems to be: more.

The day after Christmas, the snow breaks. I settle my account at the Waldhotel and order a taxi to take me to the funicular. When I arrive, it is full of holiday skiers. A man meets me at the entryway and asks for my name—he needs to phone up to the Schatzalp to confirm that I am a guest.

As we make our way to the world above, mothers hold up their children to the windows to watch Davos-Platz disappear below. At the top, a restaurant called the Snow Beach sits to the left, and to the right, a covered walkway leads to the Schatzalp. A sign posted on the walkway offers a quote from The Magic Mountain: “In life there are two ways: One is the common, direct, and brave. The other is bad, leading through death, and that is the genius way.”

The Schatzalp is a grand old dame with an operatic air, her pale yellow façade a sign of the decadence of her imperial past. I am reminded of T. S. Eliot’s refrain, In the mountains, there you feel free, and this is what the Schatzalp offers: deliverance from the world below. She is a peerless diva who belongs to another time and requires care and fortitude to keep her head up after so many years in the spotlight. Walking across the foyer, you feel as though you are stepping onto a stage. Before you, a panoramic alpine vista stretches endlessly beyond the promenade across the vast and distant valley. And gazing out, you feel your heart beat to the sublime terror of this beauty.

Each guest I meet appears like a character in an ensemble cast. There is the tall, sporty German banker who has traveled here alone for New Year’s, the Russian matriarch who wears feathers and leather and bosses the staff around, the young divorcé from Zurich who has come here with his dog, the Viennese psychoanalyst whose wife tries unsuccessfully to fetch him from the bar each night, as he orders another round of Laphroaig for the hangers-on. And there is me, the girl with a notebook and computer who sits in front of the fire, watching.

I watch the guests come and go while a bored Croatian pianist entertains himself by playing jazz. The atmosphere is convivial—everyone is preparing for a party. I find myself entangled in a conversation with a German schoolteacher who travels to the mountain every year to spend time with his favorite protagonist, our Hans Castorp. Sitting in front of the fireplace with a beer, we compare translations of our favorite passages from The Magic Mountain and discuss the novel’s most infuriating character: the narrator. For me, he is a specter who gains power from the reader’s consumption of the novel, growing more present and palpable as you turn the page almost against your will. For the schoolteacher, the narrator is a mere afterthought.

I see the hotel’s general manager, Paulo Bernardo, who welcomes me as a curious observer. “Do people come to the Schatzalp for Mann?” I ask.

“No,” he says, shaking his head. He points to a poster above the reception desk advertising a popular new television series—Davos 1917—that is shot on location here. The hotel, Paulo says, makes for a very good backdrop, and guests come to explore the set of the most elaborate show ever produced in Switzerland. He promises me a tour later in the week, but he has other things to attend to now. The hotel’s guests may have the luxury of time, but Paulo does not. The speed at which he runs from one room to the next, over the course of the coming week, gives the appearance that his clothes are always in danger of falling off.

Arriving early to breakfast the next morning, I witness a bit of a scandal in the Belle Époque restaurant: a French family has been seated at a window table that a Russian family has apparently occupied for many years. I watch as the Russian woman in feathers takes a waiter aside and scolds him. Eventually, he finds a superior who is able to make apologies, bring a bottle of something, and promise that tomorrow the table will be restored to its rightful occupant. (The next day, a plaque will appear with the family’s name next to the word reserved.)

I sit in the corner, read my copy of the Schatzalp’s morning newspaper, and admire the murals in the dining room. I catch Paulo sprinting across the room and ask him about the artwork, which depicts trees, ponds, and swans. He tells me that the paintings date to 1904 and that the pastoral scenes were chosen for guests who were afraid of heights and didn’t like to sit by the windows. The imagery was supposed to help them feel like they were down in the countryside, not up above the tree line. I go back to my paper. It will be seven degrees Celsius today and sunny, with cloudy conditions forecast for tomorrow. On the back of the paper is tonight’s dinner menu: cream of courgette soup with pomegranate foam, veal in a cream ragout with pear dumplings and colorful spicy vegetables, pears cardinal with almond tartlet, and a selection of local and European cheeses.

One of the great myths of our modern era is that we live in an age of disenchantment, an idea put forth by the German sociologist Max Weber in his 1917 lecture “Science as a Vocation.” Weber was adapting Friedrich Schiller’s term Entzauberung (meaning “disenchantment” and “the elimination of magic”) to describe a society that had lost touch with religion. For Weber, modern Western society had forsaken traditional values (the “enchanted garden” of old) in favor of a secular system governed by bureaucracy. The Magic Mountain offers a counterargument, one that I find more persuasive. Mann’s contention, born from his own political turmoil and his move to embrace democracy, is that we are living under the enchantment of World War I, which has left us in a collective stupor. For Mann, The Magic Mountain was a plea for us to wake up—so that we could at least say that our eyes were open at the hour of our death. Like characters in a fairy tale, we find ourselves frozen in time, unable to move, unable to act. The larger question at hand, posed by Friedrich Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy, is: How is meaningful action possible in this world if we cannot even save ourselves from our own death? Feeling a sense of impending doom, we turn further inward, away from the world, listening to the sound of our inner clocks counting down to our final moments. It’s as though we have heard the explosion but are too afraid to open our eyes to see which body parts might have been blown off. And frozen in this moment of terror, we invest our energy in extending life itself.

Later, as I climb the mountain in the snow, trying not to slip, making my way clumsily to the small restaurant on the Strelapass, I think about our contemporary obsession with wellness, biohacking, and optimization. By the time I reach the top, I am frozen and drenched in sweat. I order a bowl of goulash to revive myself. Up here, everything is washed in white, glistening, pristine. There is nowhere to go except farther up, mountain pass over mountain pass, one after the next—more.

As I finish my meal, I think about Chapter 7, my favorite in The Magic Mountain. It occurs to me that Weber was lamenting the wrong death. It was not the death of God in modernity that led to our disenchantment, but the death of Pan that has led to our frozen enchantment. Pan, god of shepherds and the wilds, was worshipped by the residents of Arcadia—that pastoral Eden of myth. But Pan does not belong to the world of rational thought. We have abandoned the Dionysian in favor of the Apollonian. And this, I understand now, is what Mann is dramatizing in The Magic Mountain: To wake up, Hans Castorp must cast off his Apollonian ways of reason and order, and give himself over to the Dionysian Berghof, a place of loud sex, hacking coughs, cigar smoking, endless alcohol, whistling bodies, nosebleeds, and fever dreams. Up on the mountain, chaos triumphs over order, magic triumphs over reason, and desire is unrelenting and unquenched. In Chapter 7, Hans dreams that he is Pan, returned to his Arcadian paradise:

The symphonic accompaniment sometimes fell away into silence; but goat-footed Hans continued to blow his naive, monotonous air and lure exquisitely colored, magical tones from nature—until finally, after a long pause, a series of new instrumental voices entered, tumbling rapidly, each higher than the other, their timbres rising in self-surmounting sweetness, until every richness, every fullness held back up to now, was realized for one fleeting moment, which contained within it the perfect blissful pleasures of eternity. The young faun was very happy on his summer meadow. There was no “defend yourself” here, no responsibility, no war tribunal of priests judging someone who had forgotten his honor, lost it somehow. It was depravity with the best of consciences, the idealized apotheosis of a total refusal to obey Western demands for an active life.

As I hike back down to the hotel, a feeling of euphoria washes over me. I pass the German banker, who asks whether I would like to meet him for a drink later, or perhaps go skiing tomorrow. “No, but thanks,” I say. No Apollonian men for me. Back at the hotel, as I glide across the lobby, I see the sign for the x-ray room, which has been turned into a bar. I also see to my right a sign for the sauna. I go back up to my room, peel off my wet clothes, slip into a bathrobe, and then head back downstairs. I pass through the sauna’s double doors and take a towel. The room is textilfrei, no clothes allowed. I enter the first sauna, where two women are seated, along with an older man who appears to be sleeping, though I swear I can see him gazing at us through squeezed eyelids. The women and I chat about the hotel. What brought you here? Where are you from? When I’ve had enough of this chatter, I move on. I proceed to the next room and the next, until I’ve had enough heat. Standing naked, I empty a bucket of ice water over my head. Two men applaud my bravery. I pull a robe around myself and recline in a lounge chair. Listening to the snow melt outside the window, I drift off into a deep and peaceful slumber.

By dinnertime, I’m not even sure what day of the week it is anymore. On the mountain, there is no urgency. Spa. Cocktails. Dinner. Music. Parlor conversation. This is all there is. Which appetizer do I prefer? What champagne will I choose tonight? Here, there is no war, no famine. There are no images of dying children to confront or nuclear weapons to worry about. No political referendums to ponder. All of that belongs to the world below. Up here, in the mountains, we are free.

When Thomas Mann accepted the Nobel Prize in 1929, he remarked that the conditions for artists in Germany were less than favorable to body and soul. “No work,” he said, “had the chance to grow and mature in comfortable security, but art and intellect have had to exist in conditions intensely and generally problematic, in conditions of misery, turmoil, and suffering.” Mann was not a moral philosopher. He was an artist. He was primarily concerned with the making of art, with the conditions that best allowed it to flourish. He understood the impulse to turn a blind eye and retreat to the Arcadia that is available for many. But he resisted. He knew that artists ultimately are citizens, too, and he chose exile over complicity.

On New Year’s Eve, Paulo invites me to dine with his family. It is the only time I see him sitting down all week. We are served ceviche, tomato salad, and a bread crisp to start, followed by vegetable bouillon with herb semolina dumplings, a guinea fowl breast on fennel and orange salad with cranberry gnocchi, a fried cod fillet on potato-lemongrass slaw, parsley gersotto with fried oyster mushrooms and arugula salad, a cream and mandarin salad, and a cheese plate.

At one point, I ask Paulo if I can visit the room at the bottom of the elevator where the hotel staff members go to smoke. His face flushes.

“Who have you been talking to?” he asks.

“I heard it’s the room with the door that opens to the sledge path—where they used to send the dead bodies down the mountain.”

Paulo’s laugh tells me that my intel is good. But I can’t get more out of him. Live music is playing in the dining room tonight, and the band drowns out our conversation. After dinner, there is a party in the piano bar and then goulash in the reception lounge to keep the belly full. At midnight, more champagne. And more, and more, and more.

What has all of this champagne, veal, and fresh air taught me?

While Mann was visiting Katia in 1912, he, too, was diagnosed with a lung complaint and received an invitation from the Waldsanatorium to stay on the mountain for some time. He was immediately taken with the social scene of sanatorium life, where new arrivals were announced in the newspaper’s social register—the longer one stayed, the higher one’s name rose on the list. The routine, seven meals a day, leisurely walks through the mountains, relaxation on your own sun terrace, a game of chess, an evening concert: this was all that was expected of guests. And though Mann chose not to stay, The Magic Mountain imagines what might have happened if he had.

When Mann returned to the world below, a doctor assured him that he did not in fact have tuberculosis. It turned out that Katia never had it either. Drinking another glass of champagne, I realize it was never really tuberculosis that the sanatorium was curing but rather, the conditions of modern life itself—an idea reinforced by the fact that many European sanatoriums continued to operate as lucrative business ventures even after a cure for tuberculosis was found in the 1940s. Today, they continue to be run as these wellness hotels.

Stephen Dedalus declares in Ulysses, “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” But Hans is stuck in another kind of dream. One that is less forgiving. The moment of his awakening is the moment of his death, when on the field of battle he finds himself singing Schubert as he steps over the body parts of his fallen comrades. Maybe Mann hoped that by reading The Magic Mountain, we might also awaken from our slumber. Maybe he hoped the narrator might shock us awake when in the final pages he implores us to look, shouting: “There is our friend, there is Hans Castorp!” And then makes us watch him die.

The trouble is, I’m not sure storytelling can shock the nervous system anymore. I’m afraid it is only used to create the kind of meaning that allows us to shield ourselves from this world we have made. The enchantment of The Magic Mountain is the creation of a hermetic world. Is it possible to break the spell? Mann leaves us with a question in the final lines of the book—it is the question that each new generation must decide: “And out of this worldwide festival of death, this ugly rutting fever that inflames the rainy evening sky all round—will love someday rise up out of this, too?”

The day before I leave the Schatzalp, Paulo invites me into his office. He wants to show me something.

“This is my secret safe,” he says, as he removes two pictures from a wall to reveal a replica of an advertisement for the hotel dating to 1915. Behind that ad is another poster, this one for the Belle Époque restaurant. These four layers of protection conceal an old cupboard that opens without a key. Inside is the hotel ledger from the early 1900s. We take it to Paulo’s desk and look at the numbers together. “It was the most luxurious sanatorium you could visit,” he says. “The emperor of Germany rented three rooms here from 1905 to 1912.”

I ask him how often Wilhelm II visited.

“Oh, never!” he says. “He was never here.” The rooms, it turns out, were reserved just in case the emperor ever caught tuberculosis.

I suggest to Paulo that he hire an archivist to preserve the hotel’s papers for posterity. He says he would like to do that—the position, he informs me, is available. He then tells me about a scholar in Los Angeles who is researching the guests who stayed at the hotel and is posting his findings on Facebook. He came to the Schatzalp in the winter of 2020, but then the pandemic began … and he ended up staying for several months.

“What has changed since 1900 when the Schatzalp was built? Since Thomas Mann wrote The Magic Mountain?” I ask him.

“It’s still the same. I wouldn’t say it’s changed. Just the concept—we don’t have doctors here.”

I laugh. “No doctors on the premises?”

“Okay, we have doctors,” he says. He pauses for a moment and looks up at me and laughs. Then a very serious look falls over his face. “Nothing has changed,” he says. “People still come here for the same reason. To get away.”

The passages from The Magic Mountain quoted in this essay are from John E. Woods’s translation of the novel.