Unsentimental Education

Mary Ware Dennett’s quest to make contraception—and knowledge about sex—available to all

The defendant was a gray-haired grandmother. In the courtroom in downtown Brooklyn, she sat silently as the prosecutor, James E. Wilkinson, read aloud a document she had written—a document that, according to the indictment, was “obscene, lewd, lascivious and filthy, vile and indecent.” Addressing the 12 men in the jury box, Wilkinson read it in a low monotone, except for the parts that seemed to offend him most; for these, his voice rose to a louder and more dramatic register.

The document at issue was a pamphlet called The Sex Side of Life: An Explanation for Young People. Mary Ware Dennett had written it 14 years earlier, and now, on April 23, 1929, she was on trial for having sent it through the U.S. mail.

Dennett, 57, was likely aware of the irony in this situation. Before the trial, she had been best known as Margaret Sanger’s more conservative rival for leadership of the birth control movement. Sanger had deliberately violated the federal and state laws that suppressed the dissemination of information about contraceptives, and she had served time in prison as a result. Dennett, by contrast, believed that laws should be respected, and she complied with them even as she worked to change them. Her sex education pamphlet said nothing about how to obtain or use contraception. And yet here she was, forced to come from her home in Astoria, Queens, and spend a lovely spring day inside a courtroom.

When Dennett took the stand, she explained the circumstances under which she had written the pamphlet. “When my children reached the age when they needed something beside what had been taught to them by their parents, I hunted for something to give them to read,” she began. She recounted that she had consulted some 60 existing publications but had found none of them satisfactory, so she had taken it upon herself to write one. She went on, “The manuscript of this little explanation was loaned incidentally to my friends who have children, to parents and to young people themselves. It was loaned till it was tattered.” Later, she had published it in pamphlet form and mailed copies, upon request, to individuals and organizations throughout the country.

In his closing argument, Wilkinson leaned over the rail of the jury box, waving the crumpled blue pamphlet in the faces of the jurors. He denounced it as “pure and simple smut” and accused the woman who wrote it of trying to lead the country’s children “not only into the gutter, but below the gutter into the sewer.”

Dennett was appalled by the absurdity—she’d been charged with a felony for attempting to educate children. But there was another aspect to this story that would become apparent only with time. For years, she had worked diligently on behalf of birth control and against censorship. As she sat in court that day, she had no way of knowing that this case would do far more to advance those causes than all the leaflets she had written, all the petitions she’d circulated, all those meetings with congressmen. The repercussions of United States v. Dennett, in the end, would extend to the legal status of imported Japanese contraceptive devices and the fate of a modernist literary masterpiece—and far beyond.

Mary Coffin Ware was a child of Protestant New England. Born in 1872, she grew up in Worcester, Massachusetts, and then Boston. Her extended family was on the periphery of the New England elite. Her great-uncle, Charles Carleton Coffin, had been a celebrated Civil War correspondent, and he once introduced her to Louisa May Alcott. She was also related by marriage to William Dean Howells, editor of The Atlantic Monthly.

In 1900, Mary married an architect named William Hartley Dennett, but nine years later, the marriage fell apart. Hartley had become emotionally involved with another woman, and though they were apparently not sexually intimate, they insisted on their right to a “spiritual” love. Mary sued for custody of the couple’s two surviving sons (one had died in infancy) and found herself in the middle of her first high-profile courtroom drama. The local media couldn’t get enough of the spectacle. “ ‘SOUL LOVE’ DEFENCE OF HARTLET DENNETT FAILS TO MOVE JUDGE,” blared The Boston Record. Mary won custody, but the public humiliation intensified the pain of her husband’s betrayal.

As a single mother, she needed money, and she wanted to plunge into a new life. Her old life had revolved around her family and her love of art and design. She had also been involved in various reform movements, including the campaign for women’s suffrage. With her sons temporarily in the care of her sister and soon to be in boarding school, she relocated from rural Massachusetts to New York City, took a job with the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and moved into a cramped fourth-floor walkup on West 55th Street. She was 38 years old.

In New York, her horizons expanded. She read Freud and Havelock Ellis. She joined a lively feminist group called Heterodoxy, which met regularly at a restaurant in Greenwich Village. She threw herself into her job, mediating between internal factions and churning out articles and leaflets. Over the years, she became known as a superb organizer. But she also took issue with certain decisions made by her fellow suffragists. “The suffrage movement stands for enfranchising every single woman in the United States,” she wrote indignantly to Alice Paul, who had declined to invite African-American women to a suffragist parade. In 1914, her disenchantment with the organization’s political caution, among other frustrations, led her to resign.

The country and the world were as unsettled as Dennett’s personal life. In the United States, labor disputes and unrest were frequent. In April 1914, the Colorado National Guard opened fire on striking coal miners and their families; dozens died in the massacre and ensuing riots. Social and sexual mores were shifting in the young century—especially in the bohemian circles of Manhattan, where political radicalism was also common. And then, in July 1914, war broke out in Europe. Dennett, dismayed, joined the Woman’s Peace Party, a new antiwar organization.

Amid all this, another issue increasingly captured Dennett’s attention. At one Heterodoxy meeting, a petite woman in her mid-30s named Margaret Sanger spoke about what she called “birth control,” arguing that all women needed access to it in order to control their bodies and their lives. When working as a nurse, Sanger had seen the ravages of unwanted pregnancies and the tragedy of unwanted children among the poor; she was also a radical socialist. In 1914, she assembled the first issue of The Woman Rebel, an eight-page “monthly paper of militant thought.” Without the power to determine how many children they would have, Sanger argued, working-class women were not only subject to the pain and risks of unceasing pregnancies but also forced to supply an overabundance of cheap labor to the capitalist system, keeping wages down. “No plagues, famines or wars could ever frighten the capitalist class so much as the universal practice of the prevention of conception,” she wrote.

At the time, the status of contraception was somewhat muddled. The existing methods were fairly rudimentary—condoms, pessaries (now more commonly called diaphragms), douches, sponges—and not particularly accessible. The Comstock Act (named for anti-vice activist Anthony Comstock, a crusader on behalf of Victorian moral attitudes) prohibited sending articles of contraception, as well as any information about them, through the mail, thereby severely restricting their circulation. This federal law, passed in 1873, primarily targeted erotic literature, lithographs, and other “smut” that had begun circulating widely in the mid-19th century, but the statute lumped contraception in with those materials. A couple of dozen states also had “mini-Comstock laws,” imposing their own restrictions. As a result, it was especially hard for the poor to find much-needed information. Perhaps equally to blame was the inhibited social environment: to discuss birth control or to advocate for it was taboo—something Sanger was trying to change.

Dennett was impressed by Sanger and invited her over for lunch to discuss the matter. Part of Dennett’s interest was personal. “I was utterly ignorant of the control of conception, as was my husband also,” she confided in a letter to a friend (demonstrating that even among the relatively affluent, knowledge at the time could be elusive). “We had never had anything like normal relations, having approximated almost complete abstinence in the endeavor to space our babies.” She might have wondered whether, had they had access to effective birth control, the marriage would have survived.

In August 1914, the federal government indicted Sanger for sending The Woman Rebel through the mail. In October, she skipped her court date, took a train to Montreal, and then sailed to England in early November. But before fleeing, she published Family Limitation, a 16-page pamphlet with even more explicit information on contraception. While she was abroad, one of Anthony Comstock’s agents paid a visit to her husband, William, an artist and architect, at his studio on East 15th Street. The agent claimed to be a friend of Margaret’s and requested a copy of Family Limitation. After rifling around in some of his wife’s belongings, William found a copy of the pamphlet and handed it over. Comstock himself later returned to arrest him.

Although the incident sparked outrage among Dennett’s circle in New York, she was initially hesitant to get involved, wanting to avoid press attention after the scars of her divorce. But her hesitation didn’t last. By March 1915, she had organized, with two friends, the inaugural meeting of the National Birth Control League, the first organization of its kind in the country. At the meeting, she made the case for birth control partly on the basis of the growing realization that sex could have purposes—emotional, psychological, even moral—other than producing children. She noted that “this evolved use of the sex function seems to be peculiar to the human race—an evidence of its higher development and actual progress.”

These were messages she wanted to convey not only to the general public but specifically to her sons, Carleton and Devon, who were 14 and 10 years old.

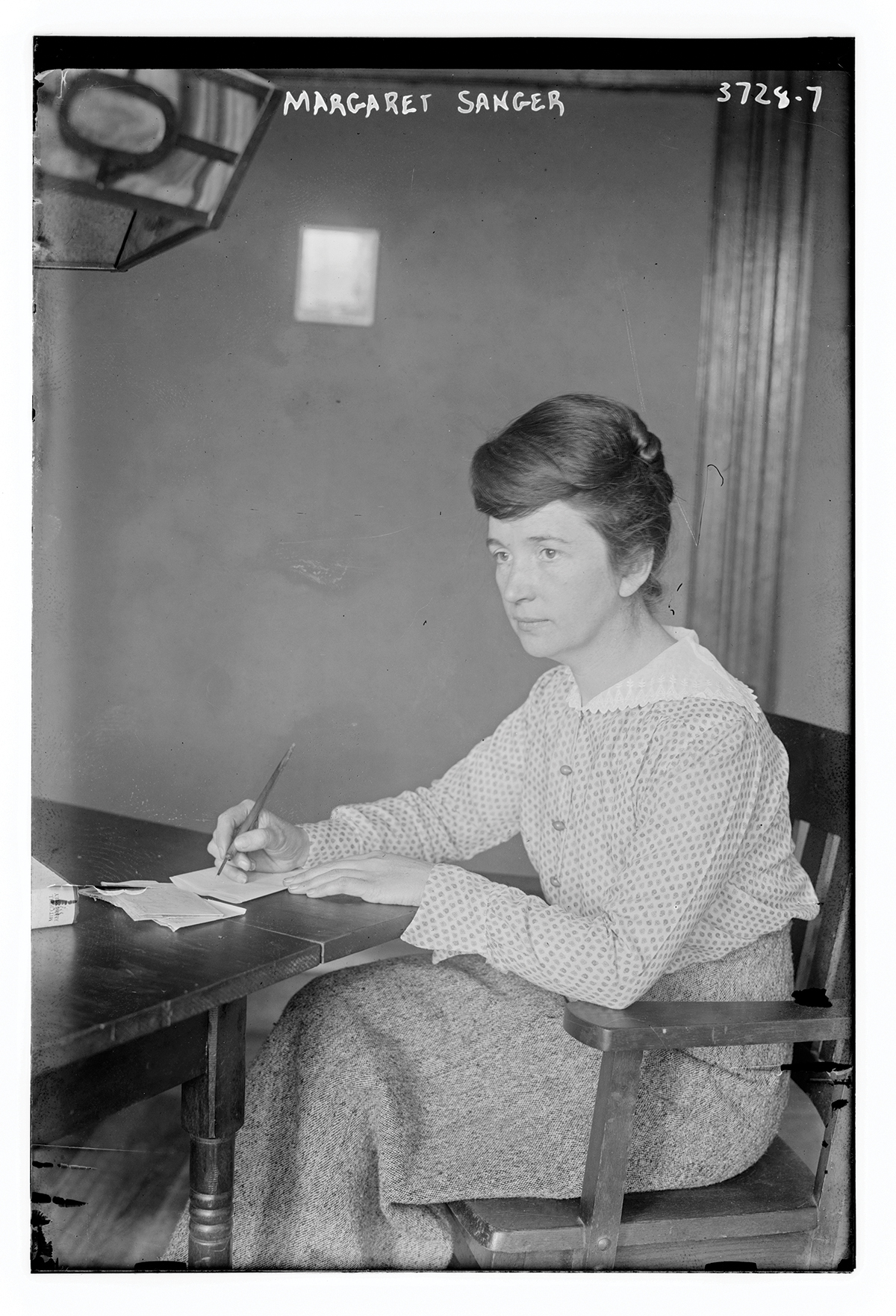

Dennett and Sanger (above) started out as colleagues, but over time their views diverged. (George Grantham Bain Collection, Library Of Congress)

When Mary was a girl, she once caught a glimpse of one of her great-aunts taking a sponge bath, fully clothed in a long-sleeved, high-necked, white cotton nightgown. Mary looked on with “fascinated apprehension” as the aunt undertook the labored process of bathing, unaware of the little girl’s gaze. Her cotton nightie flapped around as her elbows and knees contorted into odd angles. “I wondered what in the world there could be under the nightie that had to be so zealously guarded from even her own sight,” Mary would later write. “I dared not ask her why she bathed that way, but without any words at all she made me feel that I should be a very shocking and reprehensible little girl if I did not take my own bath in the same manner.”

This moment, and several others like it, stuck with her. As a bright and precocious child, she thrived in the vital intellectual and cultural world of her native New England. Yet those New England families that “produced notable citizens of high intellectual attainment, admirable civic conscience, and many recognized virtues and abilities” were also “shot through with this serious disability of a sense of fear and shame regarding sex. … They had no realization that it was like a hidden infection spreading trouble through their own lives and tainting the lives of their children.”

She was determined to raise her sons differently. So in 1915, around the time that she was cofounding the National Birth Control League—when her search for a sex education publication that met her standards proved fruitless—she set out to create her own.

For weeks, she spent her spare time at the library of the New York Academy of Medicine, on West 44th Street, poring over anatomy and physiology books. She drew her own simple diagrams and carefully labeled them. But though it was crucial to her to be scientifically accurate, what really distinguished her letter was its tone—candid, reassuring, never condescending—and its focus on both the physical and emotional dimensions of sex.

“When boys and girls get into their ‘teens,’ ” she began, “a side of them begins to wake up which has been asleep or only partly developed ever since they were born, that is, the sex side of them.” She went on, “If you feel very curious and excited and shy about it, don’t let yourself be a bit worried or ashamed. … Remember that strong feelings are immensely valuable to us. All we need to do is to steer them in the right direction and keep them well-balanced and well-proportioned.”

As she had done at the first meeting of the National Birth Control League, she drew a distinction between human and animal sexuality: “The sex attraction is the strongest feeling that human beings know, and unlike the animals, it is far more than a mere sensation of the body. It takes in the emotions and the mind and the soul, and that is why our happiness is so dependent upon it.”

The manuscript explained intercourse, conception, pregnancy, and menstruation, all in clear and simple language. Dennett also discussed syphilis and gonorrhea, two scourges of the era, and noted that treatment was increasingly effective. Many other materials at the time focused extensively on these diseases, with the aim of discouraging premarital sex. But rather than emphasize the dangers of sex, Dennett firmly emphasized the joys. She included a brief section on masturbation, which had long been seen as a terrible hazard and was a source of widespread and intense shame. Dennett wrote, “There is no occasion for worry unless the habit is carried to excess.”

She also got in a dig at the Comstock law’s section on contraception but stayed clearly within its bounds, predicting that, in the future,

people will more generally understand how to have babies only when they want them and can afford them. At present, unfortunately, it is against the law to give people information as to how to manage their sex relations so that no baby will be created unless the father and mother are ready and glad to have it happen.

The impression she really wanted to leave was that sex was healthy and good—not obscene. “Don’t ever let any one drag you into nasty talk or thought about sex,” she wrote. “It is not a nasty subject.”

On a chilly November evening in 1921, Margaret Sanger arrived at the Town Hall on West 43rd Street in Manhattan. The occasion was the concluding event of a conference intended to launch her new organization, the American Birth Control League. The title of that night’s talk was “Birth Control: Is It Moral?”

The Town Hall, a stately brick building with a large auditorium, had been erected earlier that year by the League for Political Education, a suffragist group. Tasteful chandeliers hung from the high ceilings; 1,500 seats filled the ground floor and a balcony. That Sunday evening, the doors had opened at seven p.m., and hundreds of people had poured in. Sanger was still outside, along with Harold Cox, a former member of the British Parliament who was also scheduled to speak, and hundreds of others waiting to be admitted. Limousines were lined up on 43rd Street.

At about 8:00, however, the police arrived, announcing that the meeting was canceled and closing the doors. The people inside could not get out. But outside, the size of the crowd only grew.

At about 8:30, Captain Thomas Donahue announced that the doors would be opened to allow those inside to leave. Instead, the assembled throng was able to bypass the police, sweep Sanger and Cox inside, and lift Sanger onto the stage. Shouts of “Defy them! Defy them!” came from throughout the hall. “Go on with the meeting,” someone called. When Sanger attempted to speak, two officers walked up to her on the stage and grabbed her arms. “You can’t speak here,” one of them said. “They don’t dare arrest you,” a woman cried. “Where’s the warrant? What is the charge?” Dozens of audience members, including Sanger’s close friend and colleague Juliet Barrett Rublee, jumped up onto the stage to try to stop the arrest.

As the audience erupted into “My Country, ’Tis of Thee,” the policemen led Sanger away, taking her up Eighth Avenue to the police station on 47th Street. A large crowd followed.

Dennett was not in the audience that night. She was sick at home, and besides, she and Sanger were not on good terms. After Sanger’s return from Europe in 1915, she and Dennett had collaborated on occasion; they were both involved in launching the Birth Control Review, a monthly publication. But over time, the conflicts between them grew increasingly pronounced. When Dennett learned of Sanger’s intention to found the American Birth Control League, she argued that it would be more efficient and effective to consolidate efforts instead of having rival organizations. But Sanger repeatedly rebuffed her.

Just a couple of weeks earlier, Dennett had hosted Marie Stopes, the British author of the controversial book Married Love, for a talk about birth control, also at the Town Hall. The tension between Dennett and Sanger had come to a head when Sanger tried to dissuade Stopes from associating with her rival. “I personally consider Mrs. D– outside the pale of honesty & decency,” Sanger wrote—a message that Stopes then relayed to Dennett.

Still, when she heard about the hubbub at the Town Hall that Sunday night, Dennett felt compelled to defend Sanger, even though she was feeling ill. After all, her own meeting on the same subject had been allowed to proceed in peace, and Sanger, she knew, deserved the same right to free speech. At the police station, she looked for the officer in charge, but he was nowhere to be found. So she decided to speak with the press instead, navigating through the crowd gathered outside. She waited until Sanger had finished her account, and started to add her own contribution. According to Dennett, that’s when Rublee, who was standing in front of her, turned and jabbed Dennett with her arm, forcefully enough that, Dennett later recounted, she would have fallen if not for the density of the throng. “This is our affair, we don’t want you in it,” Rublee told her.

The incident encapsulated a lot about the relationship between Sanger and Dennett, the former charismatic and media savvy, the latter principled almost to the point of absurdity. Certainly, the acrimony between them was partly personal. Sanger could be tremendously loyal to and supportive of her friends, but she felt she deserved to be the undisputed leader of the movement, and she could brook no threats to her primacy. Yet there were also genuine differences of opinion over tactics, goals, and the direction of the movement—and they reflected evolutions in both women’s thinking over time.

Although Sanger had started out as a radical, she gradually brought her movement firmly into the mainstream, establishing organizational infrastructure and recruiting influential “club women.” In the same vein, she sought to establish alliances with the medical community. Starting in 1924, the American Birth Control League promoted what was known as a “doctors only” bill, which would amend the Comstock law to permit physicians, but no one else, to mail contraceptive devices and information. Sanger believed that this would help guarantee that women had access to quality birth control—that is, it would be a defense against quacks and charlatans. As she wrote in the Birth Control Review, if just anyone were able to send such information through the mail, the “result would be, that while women were debarred from real scientific knowledge of the subject, they might through the mails receive information entirely unsuited to their needs.” She also thought that having the medical community on board was key to public acceptance and political progress.

Dennett, however, deplored the idea of a doctors-only bill. Her organization—by this time reincarnated as the Voluntary Parenthood League—advocated for a “clean repeal,” which would simply strike the text related to contraception from the Comstock law. This was much more in line with Dennett’s values: she believed in the free circulation of information and education as the antidote to ignorance and misinformation. She also worried that the exception for doctors would leave in place the impediments for many poorer women to receiving the information they needed:

[It] would create a complete medical monopoly of the dispensing of the information; would give doctors an economic privilege denied to anyone else; would treat this one phase of science as no other is treated, that is, make it inaccessible to the public, except as doled out via a doctor’s prescription, as if the need for the knowledge were a disease.

She also felt strongly that it was important to sever any link—in the law and in the public mind—between birth control and obscenity. By leaving that part of the Comstock law intact, the doctors-only bill would do nothing to eliminate that association. Though Sanger was known for her earlier fiery language and brazen lawbreaking, by this point, in some ways at least, Dennett had become the more radical figure.

Dennett and Sanger also differed in the arguments they made on behalf of birth control. Sanger saw it as all but a panacea—not only the key to sexual and feminist liberation but also a cure for everything from poverty to overpopulation to war. Dennett was both more principled in her reasoning on behalf of birth control and more intellectually rigorous. At the same time, her reasoning was simpler. She believed that couples should be able to separate their sexual lives from their reproductive lives, and she believed that all people should be able to decide on their own how many children to have.

In August 1924, Dennett submitted a 3,600-word essay titled “Birth Control, War and Population” to The Century, a prestigious general-interest magazine for which she had written in the past. “So far as I know,” she typed in her cover letter, “nothing has yet appeared in any of the major magazines to counteract the cheap and easy current fallacies as to birth-control.” In the essay, she wrote, “There are current[ly] many sweeping claims for birth control as a preventive of war, and there is much talk about ‘overpopulation’ as an existing or threatened danger that can be mitigated only by birth control.” Asserting her strong support for birth control, she asked, “Is it wise for enthusiasts in the birth control movement to let their zeal lead them into making greater claims than facts can warrant?” She referred to an idea that was gaining traction—that countries should “limit their populations to their own resources.” The idea, she wrote, seemed to be that governments would mandate birth control. “The mental picture which the idea creates is one of appalling paternalism, as well as a shockingly unthinkable intrusion upon private life.”

She went on to note “two scares” prominent in the birth control movement: the first one, which, she said, was promoted by Sanger and her allies, was “that the world is sure to run short of food sometime, and certain countries are scheduled to run short very soon, which will cause war.” The second, promoted not by Sanger but by others, was “that the more prolific, undeveloped, unfit and dark-skinned peoples are sure to overwhelm the less prolific, highly civilized, more fit white skinned peoples.” Dennett objected to both arguments. She contended that, given access to contraception, along with education and economic opportunity, parents would opt to use birth control “for the welfare of their own families. … Education and economic opportunity are well worth worrying about in every country, but ‘overpopulation’ is not.”

When the editor of The Century passed, Dennett sent the manuscript to other prominent newspapers and magazines of the day, from The New Republic to The Saturday Evening Post. All of them turned it down. Most did not give reasons, but an exception was an editor at The Nation who wrote, “The fact is, I think it hardly worth while, whether they are right or wrong, to attack quite so violently your opponents, who want, after all, just about what you want.” After receiving more than a dozen rejections, Dennett filed the essay away.

By 1929, the year she was indicted, Dennett’s hard work on behalf of birth control had apparently been in vain. She and Sanger had not been able to unite behind a federal bill, and although Sanger had made headway on other fronts, neither of their preferred bills ever passed. But perhaps it was some consolation that the “little explanation” Dennett had written for her sons and then published as a pamphlet was widely considered to be among the best sex education materials available at the time. Churches, schools, and the YMCA distributed thousands of pamphlets all over the United States. She also fulfilled individual orders. For 25 cents apiece, she would send a copy through the mail; for bulk orders, she charged 15 cents per pamphlet.

The indictment, which Dennett found among a pile of New Year’s greetings in early January 1929, was not completely unexpected. The post office had notified her years earlier that it had deemed the pamphlet “unmailable” under the Comstock law. She had repeatedly requested an explanation, or at least a specification of which parts of the pamphlet were considered obscene, but to no avail. So she had continued to send it. Although she didn’t like to break laws, she refused to comply with capricious, unreasonable demands; she suspected she had been targeted because of her work to change the Comstock law. As she later wrote,

Obscenity differs from all other ‘crimes’ in that it is not legally defined. It is whatever any legally empowered officials choose to think it may be. … As I knew that this pamphlet did not reflect any obscene thoughts from my own mind, but could be deemed obscene only because of what was read into it by minds in which sex dirt had previously lodged, I of course would not allow the Post Office decision to affect my actions.

Dennett had even contacted lawyers at the recently founded American Civil Liberties Union to discuss a challenge to the post office’s ruling in court, as a kind of test case. But the post office moved first, and she was indicted. One of the ACLU lawyers she had been in touch with, Morris Ernst, immediately agreed to represent her free of charge.

In the courtroom that April day, the 12 men of the jury (New York State did not allow women to serve at the time) deliberated for about 45 minutes before filing back into the jury box at 5:30 p.m. The foreman partially rose from his seat, holding his overcoat and hat in his lap, and said in a muffled voice, “We find the defendant guilty.”

Dennett was sentenced to a fine of $300, which she promptly refused to pay. Ernst announced that they would appeal the verdict. Newspapers throughout the country came to Dennett’s defense. A New York Times editorial lamented that the decision “shows once more in what a confused and unsatisfactory condition is the law covering such cases.” In The San Francisco News, an editorial stated: “This miscarriage of justice has aroused citizens everywhere to the menace of an archaic and unscientific attitude toward sex education. … We do not believe that the enlightened American public will stand for such suppression.” Dennett was inundated with letters of support. A group of prominent citizens formed the Mary Ware Dennett Defense Committee, with the philosopher and reformer John Dewey serving as chairman. The committee held a meeting at the Town Hall, attended by about 1,500 people.

In 1930, a three-judge panel on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in Dennett’s favor. In his decision, Judge Augustus Hand wrote, “The defendant’s discussion of the phenomena of sex is written with sincerity of feeling and with an idealization of the marriage relation and sex emotions. … We hold that an accurate exposition of the relevant facts of the sex side of life in decent language and in manifestly serious and disinterested spirit cannot ordinarily be regarded as obscene.” The decision was widely celebrated, and the government elected not to appeal.

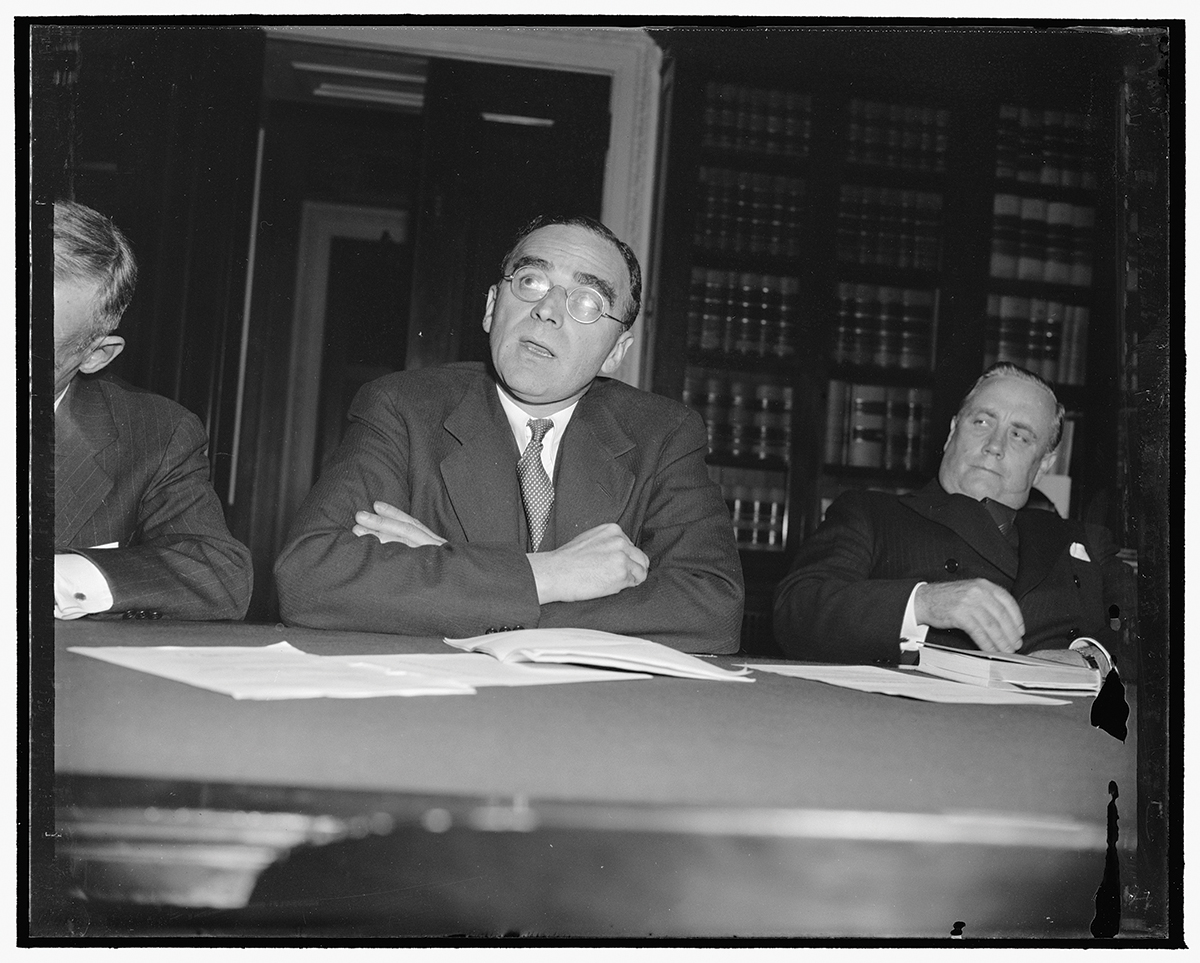

For Morris Ernst, the case was one of the first in a long and illustrious series of successes in his battle against censorship. Ernst was a complicated figure who allegedly worked as an informant for the FBI, but his record in court was impressive. In 1931, he defended the book Married Love, by Dennett’s close friend Marie Stopes. He argued that Stopes’s book was essentially doing for adults what Dennett’s pamphlet had done for adolescents, and the judge agreed. Ernst then successfully defended Stopes’s book Contraception, which broadened permissible content to include information on birth control, not just sexuality—another milestone.

But Ernst not only had his eye on the dissemination of information, he also wanted to fight on behalf of literature. In the early 1930s, he took on the case of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which had been banned from importation because of its treatment of sexuality and its inclusion of language deemed crass. He won, in a historic victory for literary expression. He also defended Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, about life as a lesbian, and other books now forgotten. Then, returning to contraception, he won the landmark 1936 case United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries, with Sanger’s colleague Hannah Stone as his client. This case overturned the prohibition against importing contraceptive devices into the country and then went further, permitting physicians to freely prescribe birth control.

As Laura Weinrib, a professor at Harvard Law School, has written, United States v. Dennett, though “often overlooked in histories of free speech,” was in fact seminal. “Dennett’s heavily publicized conviction, overturned by the Second Circuit on appeal, generated popular hostility toward the censorship laws,” Weinrib wrote. “In the months after the Second Circuit’s decision, the ACLU took advantage of the popularity of the Dennett case to re-evaluate and expand its position on censorship.” The case, she argues, was “a landmark event in the history of civil liberties. … The very fact of winning in United States v. Dennett made a broader agenda seem possible.”

Following his successful defense of Dennett, Morris Ernst took up several anti- censorship cases, including that of Joyce’s Ulysses. (Library Of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

In the years after her trial, Dennett published a book about the experience (called Who’s Obscene? ) and then a short volume, The Sex Education of Children, expanding on the philosophy embodied in her pamphlet. The pamphlet’s new fame led to a surge in demand, which Dennett scrambled to meet. She still didn’t care for publicity, however. She turned down public speaking invitations, preferring to spend her time reviving an earlier passion: a form of leatherwork craft she had mastered in her youth.

Since her death in 1947, Dennett has been largely lost in the shadows of her more glamorous nemesis, Margaret Sanger, who has been rightly remembered as an icon of women’s rights. But in recent years, Sanger’s star has dimmed because of her connection to the eugenics movement. In Sanger’s time, eugenics was mainstream—even considered progressive—and had various meanings; for her, it was not race related, but she did believe that those with hereditary disabilities should not reproduce, and her statements about the “mentally and physically defective” are now painful to read. For years, she has been accused of a racist agenda by opponents of Planned Parenthood, the present-day successor organization to the American Birth Control League. More recently, amid self-reflection on the left, Sanger’s own heirs have also grown increasingly critical. In July 2020, the Greater New York chapter of Planned Parenthood decided to remove Sanger’s name from its Manhattan clinic, because of her “harmful connections to the eugenics movement.”

Challenges in appraising historical figures are obviously not unique to Sanger. The most vexing cases are the leaders and pioneers to whom we are indebted but who held views we now find misguided or even repugnant. If the Planned Parenthood chapter determined that its links with Sanger no longer served its mission, dropping her name was of course its prerogative. But perhaps the rest of us ought to be capable of honoring her monumental achievements even as we recognize her significant flaws. To value contributions from people in the past—or in the present, for that matter—is not to condone their every action and belief.

It would be tempting to hold Dennett up as a pure, unsung heroine, but she is not entirely exempt from association with the now-disgraced ideology, either: when lobbying Congress, she solicited endorsements from the Eugenics Advisory Council for her preferred bill. Still, for the most part, her views have aged quite well. Though it’s hard to say in retrospect who had the better argument on tactical grounds regarding the clean repeal versus doctors-only bill, on principle Dennett’s more democratic stance has undeniable appeal. In March 2020, Time magazine published an article called “9 Women from American History You Should Know, According to Historians.” Lauren MacIvor Thompson chose Dennett, lauding her vision for reform as “more expansive” than Sanger’s:

Sanger wanted to ensure that birth control remained under the control of physicians and thought medicalizing it was the best path for social acceptance. … It is interesting to think about how our understanding of contraception and reproductive rights might be different had Dennett prevailed.

Dennett’s simple, principled reasoning for why people should support birth control has been vindicated by history. Her manuscript warning of the “appalling paternalism” implied by some of the contemporaneous arguments for contraception, as well as their racial overtones, was prescient. (It also suggests that, whatever her reasons for reaching out to eugenicists, she did not buy into their most pernicious beliefs.) Starting in the mid-20th century, global efforts at population control did result in a “shockingly unthinkable intrusion upon private life,” especially in countries such as India, where forced sterilization was widespread, and China, with its one-child rule. The difficulty Dennett faced in trying to publish her essay, apparently in part because it dissented from her own side’s orthodoxy, should also give us pause about dismissing ideas that don’t adhere to current fashion.

As for sex education, her pamphlet would today seem not only innocent and tame but also noticeably retrograde in certain ways—chiefly in its assumption that all of its readers would share the same desires. Sensitively written sex education materials now acknowledge a broad range of sexual desires, practices, and identities. Still, Dennett’s honesty and her attitude—what we might today call “sex-positive”—represented a large step forward for sex education. She was strong willed, brilliant, and imperfect. All of us are shaped to some extent by the assumptions that surround us. More than most, Mary Ware Dennett was both able to recognize sophistry when she saw it and willing to do something about it.

Author’s Note: To write this essay, I relied heavily on several books. Paramount among them were books by Mary Ware Dennett herself, particularly Who’s Obscene?—in which she recounts her trial, the circumstances leading up to it, and the aftermath. I also drew on The Sex Education of Children and her first book, Birth Control Laws: Shall We Keep Them, Change Them, or Abolish Them. Another key source was the archive of Dennett’s papers, collected at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, where I found her unpublished manuscript, “Birth Control, War and Population.” And I relied on Constance M. Chen’s 1996 biography, “The Sex Side of Life”: Mary Ware Dennett’s Pioneering Battle for Birth Control and Sex Education as well as The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 1: The Woman Rebel, 1900-1928, edited by Esther Katz, Cathy Moran Hajo, and Peter C. Engelman. For some of the material on the rivalry between Dennett and Sanger, I consulted a resource titled “How Did the Debate between Margaret Sanger and Mary Ware Dennett Shape the Movement to Legalize Birth Control, 1915-1924?” This resource is a collection of letters from Dennett, Sanger, and others, curated and placed into context by Melissa Doak and Rachel Brugger. It is part of Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000. Finally, for certain details, such as the description of the police raid on the Town Hall, I drew on contemporaneous accounts in The New York Times.