Two weeks into the school year, my daughter’s kindergarten classroom held visiting day. Her school—“Little Fireweed”—is named after a common Alaskan wildflower. By midsummer, fireweed has grown head-high in vast swaths across meadows and along roadsides. It blooms fuchsia in July, starting with the flowers at the bottom of the large cone-shaped plant. Each new bloom opens above the one that came before it, rising to the tip of the cone. When the final bloom opens at the very top, the saying goes, it will be six weeks until winter. And we get a hint of winter when, after the blooming is done, the plant’s seedpods release white cotton silks that catch the wind like dry snowflakes.

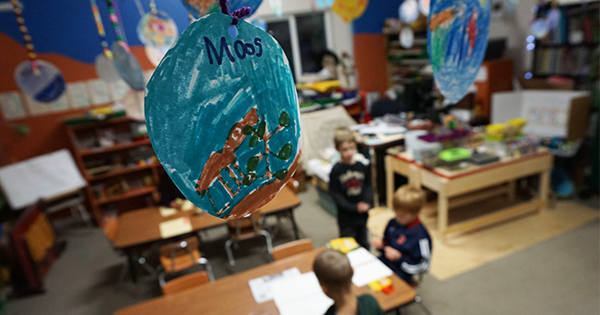

Parents were invited for “circle time” at Little Fireweed, and we hunched along the edge of a round rug on tiny plastic chairs—some of us with restless younger children at our sides—as the class of 13 went through its morning routine. The teacher, Miss Kim, is a warm woman with long gray hair pulled back off her face. She wears socks under her sandals and, although she is white, often wears a kuspuk—a Native knee-length, hooded tunic that has become popular among Alaskans of all kinds and has even prompted “kuspuk Friday” among our state legislators.

Traditional kuspuks are made from skin or gut, but the common ones these days are printed cotton with rickrack trim. When Miss Kim wears hers, I picture her sitting far out on the tundra picking berries, ringed by her charges. She hugs the children and gently coaxes the ones who are shy, who won’t talk or sing, who look at the ground or put their hands over their ears to come back onto the rug.

The first question at circle time: What is your favorite thing to eat out of the garden? It was the end of August. Vegetable patches were still going strong. There hadn’t yet been a frost, and the first snowfall of the season was a month away. Sweet peas, strawberries, carrots, the children answer in turn around the rug. Some kids pass. One child, a beautiful part-Native girl with long shining brown hair and large dark eyes, says nothing. Then the group starts to sing:

The silver salmon leap through the air,

Missing the claws of the big brown bear.

They flick their tails at the hungry boar,

Then splash away from his mighty roar.

After circle time, we celebrate with a snack. Sarah, the mother of one of the quiet boys, is a commercial fisherman in Bristol Bay and has brought in smoked red salmon cut into finger-length sections with the bright silvery skin still on. There are frozen raspberries from someone’s yard and wild blueberries with yogurt in small paper cups. We all know this food. Even the children know how to peel the skin off the fish and gnaw the chewy salmon. We all dig in.

Like most Alaska residents, I am not from here. My people are not from here. To feel like I belong is a choice; it’s a way of living. So we devise our own customs and create our own traditions.

Circle time tells me a lot about the place where I am trying to belong, the place where I live and where I’m raising my children. What is important for us to talk about at the beginning of the day? How do we measure the passing of time? About what do we sing?