Waiting for Fire

As smoke thickens and ash falls, an esteemed Napa vintner prepares to save his home and livelihood

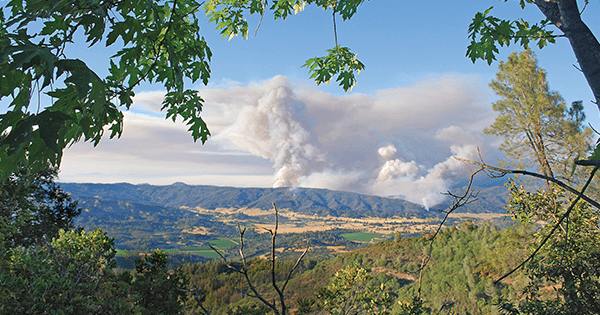

The Valley Fire began on September 12, 2015, and spread to 76,000 acres in Northern California’s Lake, Sonoma, and Napa counties before it was extinguished weeks later. Four people died, and nearly 2,000 buildings, including 1,200 homes, were destroyed.

Smoke hangs in the branches of Douglas firs massed on the ridge line. On most days, Randy and Lori Dunn, who live just below it, can see the ragged palisade clearly. But on this September day in Napa County, the trees are indistinct, receding farther as the day progresses and the sky darkens. By 7 p.m. it is black, and although the fire is still a dozen miles away, the smell is inescapable.

The Dunns close the windows, turn on the air conditioner, and go to bed. At 2:30 a.m., they wake up to flashing lights in the driveway: the sheriff has arrived to tell them that a 50-mile-an-hour wind is blowing the fire their way, and White Cottage Road is being evacuated. Since Lori has recently undergone shoulder surgery, this news means putting on a sling before she can place framed photographs of children, parents, grandparents, and friends into a cardboard box with one hand.

That she has to choose which faces to save and which to discard does not seem fair at such a lonely hour. Randy taps his iPad to track what is being called the Valley Fire—not for Napa Valley, but the valley to the north, in Lake County, where 40,000 acres have burned already. It is safe to say the fire is out of control despite a score of fire engines, two dozen dozers, and a thousand souls laboring to contain it.

If the fire comes farther south, it might well climb Howell Mountain’s northern flank, race along the ridge, and come down through the firs and ponderosa pines that extend into the very midst of their lives. Then it could consume things as precious to the Dunns as their photographs: house, outbuildings, a couple of million dollars’ worth of bottled cabernet sauvignon, and the new 2015 vintage still on the vines; also a vegetable garden, the huge fig tree dropping more fruit than they and the birds could eat, and nearby Wildlake, 3,000 acres of wilderness high on the eastern perimeter of Napa Valley. The Dunns have saved it once before.

Lori takes off her brace in frustration and carries the box of photographs out the kitchen door, past a sign that reads Grandma and Grandpa’s House: Memories made here, and down the outdoor stairs to the little cave where some Dunn wine is stored. She leaves the box there and goes back upstairs for her sewing machine and collection of quilts. Then she hugs Randy and, still in her pajamas, gets into their white SUV to drive to the relative safety of St. Helena, a vertical half-mile below.

Randy—in Levi’s, boots, and a T-shirt bearing the silhouette of his turbo-prop Commander parked a mile away at the Angwin airstrip—now has to decide what job to do first and the order of all those to follow.

On the phone, he is laconic, even on such a day, for that is Randy. Yes, the fire’s close, he tells me, likely to get closer. Sure, he could use another pair of hands. I’m at the bottom of Napa Valley, working on a book, and I put on hiking boots and drive the 20-odd miles north with a water bottle and a hat, not knowing quite what to expect.

Cars are coming down Howell Mountain, but a few are going up, too, and I join them, topping out on a country road overlain with low, scudding clouds pierced by intermittent sun. The way into the Dunns’ property turns from tarmac to dirt, and at the end of the road an ancient D4 Caterpillar snorts in its labors, flaking yellow paint with rust showing through like industrial pentimento. The machine seems too simple to be effective, yet Randy has built a firebreak, trenching the edge of the sunflower field and pushing up windrows of dirt, rock, and dry pine needles blown from the big trees.

The dozer was Army surplus, rebuilt in Okinawa after World War II and later put up for sale. Randy bought it in the town of Tulelake decades ago and drove it home on a borrowed flatbed truck, anticipating his future as a successful and, as it turned out, highly individual maker of fine wine in the modern heart of American viticulture.

It’s 9:30 A.M., and Randy’s Levi’s and T-shirt are already filthy, a fitting match for the dilapidated straw hat sitting crookedly on his head, his white mustache a gleaming brushstroke in the brim’s shadow. Behind him is a dusty horse paddock, a stand of apple trees, and a sprawling woodshed and machine shop, its bat-winged corrugated iron roof held down with heavy stones. Mounted on the gable is a neon sign shaped like a bottle, made by a friend from vintage bits of salvaged tubing. It will announce, the next time it’s switched on, Wine!

A pickup comes barreling in from White Cottage Road, loaded with all-terrain bicycles. The beefy driver brakes and leans out the window. It’s Mike, Randy’s stepson and Dunn Vineyards’ official winemaker now, involved in all aspects of the growing and rendering of cabernet sauvignon. Unshaven, smiling crookedly, he seems the picture of affability. But the conversation is pointed: the fire’s said to be moving in on the golf club at Aetna Springs, in nearby Pope Valley. Then Mike asks, “Did the horses get into the vineyard?”

They did not, but if they have to be let out of the paddock, they know their way around the property and will have a good chance of surviving. “They’re hungry,” Mike adds. “I think I’ll go get them a bale.” And he’s gone again.

The landscape has been exhausted by years of drought, and the understory of the tall oaks and conifers is bleached. In the distance, tree trunks stand out as dark slashes in brittle blond stubble, the madrone branches and pine needles as dry as dust. What has always been comforting to the eye is now vaguely threatening.

Waiting for fire inspires an almost easeful fear, as if the threat can be banished at any moment—a lessening of the wind, a bit of rain—but it’s an edgy gamble. Whether the fire will appear suddenly and ruin their lives, possibly even claim them, or turn and consume the next ridge over, is impossible to foretell. Information about a fire’s progress is not often available—the official Cal Fire website is busy and difficult to navigate—and fire is a constantly mutating menace that only those in the middle of it can truly know.

By 10:30, the smell of smoke is stronger. Though the barely detectable breeze is southerly, a big fire can create its own dynamic. Low clouds presumably have kept the bombers from flying in with their loads of liquid fire retardant. No one knows for sure what’s going on, only that Angwin airport is closed and people are fleeing. Randy went there earlier to move some fuel away from his plane in its hangar. Now he starts up the D4 again and mounts it, headed for a last line of windrow between the flats and the hill.

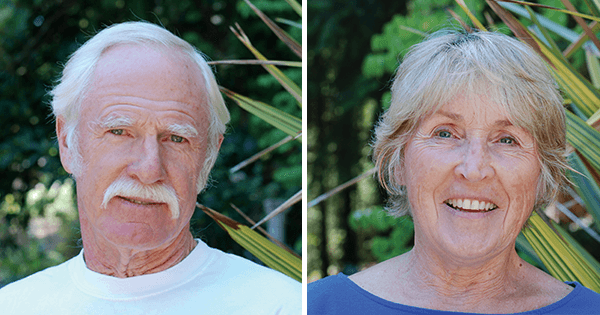

A quarter-mile up that steep dirt road and just over the crest is the Dunns’ estate vineyard. In 30-odd years, it has earned a reputation for wines of longevity, tannic density, and beautiful bottle bouquet after a decade or more of age. Lean, intense fruit is part of that reputation, in direct contradistinction to the upfront jammy embrace and riveting alcoholic follow-through of most popular high-end Napa Valley cabernets.

Vineyards are good at thwarting flames, providing little fuel, but this one would make a very expensive firebreak indeed. Wine from its fruit paid for the Commander and its lesser predecessors, including a secondhand 1946 drag-tail Aeronca Champ, in which Randy once courted Lori. It also paid for the Diemme grape press, the tunnels in the mountainside, and countless French oak barrels. This was long before Randy, in the final rigors of earning his PhD in entomology at UC–Davis, took an elective course in enology. He started making the stuff in a plastic barrel in the back of his used Ford Econoline van, sloshing nascent wine onto the floor as he circumnavigated Lake Berryessa between Davis and Napa Valley, where he worked for Caymus Vineyards.

Randy and Lori Dunn: they founded Dunn Vineyards in 1979 in Napa, and raised their family there while making critically acclaimed cabernet.

Her face drawn, Lori returns from church in St. Helena midmorning. “The fire will get to Wildlake before it gets to us,” she says, her voice breaking. “There’re mountain lions up there. And deer, bobcats, bears.” She hurries up to the house to collect more valuables.

Their daughter, Kristina, and her daughter, Taylor, live just down the road, but they spent the night with relatives in St. Helena and will stay there tonight, too. The nagging ambiguity of the day is shared by the hundreds who have fled Lake County and flocked to the Calistoga fairgrounds, having lost their homes. Many are bunking with friends, family, or employers on the Napa Valley floor: pourers, waiters, barkeeps, forklift drivers, flower arrangers, pruners, punchers-down of the floating caps of grape skins in stainless steel fermenting tanks, and caterers who often have to cross a mountain range on two-lane roads twice a day to get to and from work.

Randy walks up the sloping drive to the house, past his Ford 250 loaded with a ladder, wrenches, gas cans, rope, and an all-terrain vehicle that could get him back up here if he has to evacuate but finds the road to Howell Mountain blocked. Houses lost to fire often don’t have to be. A person on the scene can preserve them, but it’s risky. On Randy’s back seat is a lemon-yellow flame-resistant fire suit, a helmet, and a gas mask.

Next on the to-do list is the cleaning of the house’s gutters, which are full of fir needles lofted there by wind the day before. The roof is metal, but an ember in a gutter can burn down even a concrete house if conditions are right—and the Dunns’ house is made of wood. He drives the forklift up to the back door as a tethering point and fetches a climbing rope for belaying.

His son-in-law, Brian, has showed up to help, and Randy presses both of us into service: Brian is the gutter man, and I’m the belayer. Wearing aviator shades and shorts, Brian clambers up the ladder, dons the safely harness, and applies the furious leaf-blower, walking crabwise with one hand on the rope down to the far edge of the roof. He’s a professional firefighter in Sonoma County, and he will have to go back there before day’s end.

We then clean the gutters at the winery office, a house built in the 19th century by Italians who used the cellar for winemaking. A full century later, Randy Dunn would use it, too, climbing over casks on a dirt floor, employing a tool called a wine thief to draw long vials of cabernet from bungholes into antique glasses, raising them speculatively to his nose. The house had belonged then to Charlie Wagner, owner of Caymus Vineyards, down the mountain. Warren Winiarski, winner of the Paris Wine Tasting of 1976, also had lived there with his wife, Barbara, and their small children, in what was then deemed a backwater unsuitable for grapes, being too far removed from the vaunted valley floor. Now this land is as sought after by potential growers as any terroir in Napa. The old viticulturists’ redwood stakes are still sometimes found in the woods.

Randy made Charlie Wagner’s wine for him in the 1970s and ’80s. In those days, Randy looked a lot like Robert Redford—same beard, same abundant strawberry blond hair. Charlie allowed Randy to press his own grapes at Caymus and bring the juice back up to White Cottage Road, where it was transformed into the first versions of what would become the distinctive, surprisingly successful Dunn cabernet sauvignon. The praise it received then was the beginning of Dunn cabernet’s steep critical climb, and he and Lori soon bought the house.

In Randy’s early days of ownership, the house had swaybacked floors, streaked walls, and Victorian sash windows with wavy glass. After he and Lori built their own rancher next door, this place stood empty. One night a mountain lion saw the moon’s reflection in a window and leapt through. The next morning, Randy found shattered glass, the curtains in shreds, and a single drop of blood on the floor, shed before the big cat leapt through another window and was gone.

Brian comes down the ladder and drops the leaf blower and harness. He has scoped out the fire from bits of news he has picked up, but even professionals like him have had trouble getting good information. “It’s probably going to jump to the next canyon,” he says. “If it does, it’ll come straight through Wildlake.” After that, it’s anyone’s guess, but the fire will move quickly through the chaparral. “The real problem’s going to be blowing embers.”

Everyone congregates in the kitchen to eat Lori’s chicken salad sandwiches and drink cold grape juice made from a mix of Ruby Red grapes and unfermented Dunn cabernet. Brian says, “If it happens, a brush unit will come through to save what they can, and move on.”

The brush units put out spot burns, essentially pushing the fire around a house. But not if the owner hasn’t made any preparations, or if there’s no water and it looks hopeless. Wildfire triage.

Son Mike comes in briefly in his Aussie boots, shorts, and a sweat-stained T-shirt over his barrel chest. He’s headed home. He, Kara, and their kids live on the north end of the ridge and are vulnerable, too, though their metal-roofed house is covered in stucco. “I guess I’ll go back,” he says, almost casually, “and get up there, and see what I can see.”

As he leaves, Brian tells Randy, “If I were you, I’d make a sign and put it up on the road. I’d spray-paint the address and the words Defensible, 10,000 gals. Pond and pool. That’s what I’d do.”

The Dunn’s machine shop and shed are not readily comprehensible to a visitor. Surely any mechanical problem in small-scale viticulture can be solved here, but first you must know where to look: rebar, metal and plastic pipe, boards, enigmatic tools, machines for fixing other machines, a wall of dusty chainsaws, a forest of wrenches both new and grimy, a wall of fittings great and small for every imaginable coupling, and various other mysteries from the deep industrial past.

Take the drill press that once lived in the hold of a ship-—its battered, Darth Vader visage towering over a new bit that could drill through a foot of steel. Randy bought that, too, in the ’70s, from thirdhand UC–Davis surplus. It weighed half a ton, and he brought it home on the same flatbed that had moved the D4. Ask why, and he’ll say, “It was too beautiful to pass up.”

What the shed and shop don’t have, however, are workable spray-paint cans. Randy and I have penciled Brian’s words on a piece of plywood, but the first can he tries is clogged; the second fizzles. The only working one contains orange paint that’s too pale to be seen at a distance, so the letters must be traced again with a succession of parched black Magic Markers. The words go on, but there’s no room for “pond and pool,” so another board is propped up and assaulted with orange paint.

Randy tosses a hand drill and some sheetrock screws into the back of a golf cart that is now a wheezing farm runabout. We take off, passing the roan gelding on his back in the paddock, rolling in dust.

White Cottage Road is deserted. We prop the first sign against the mailboxes, and Randy screws the second one high against a runty oak. A sheriff’s cruiser speeds past, and the deputy’s head whips sideways to take in Randy’s handiwork. Tomorrow, Dunn Vineyards is to be visited by the influential wine critic Antonio Galloni, who has come from New York to taste Napa Valley’s best, including a succession of Dunn vintages. Most vintners in such an enviable position wouldn’t want to greet their estimable guest with odd, hand-painted messages in lurid colors, but the signs could give the vineyard a chance.

Overhanging boughs of live oak, Doug fir, and madrone might deter a passing fire truck in the heat of battle, so we drive back to the shed to get the forklift, one of the white plastic bins used for hauling grapes, and a chainsaw. Soon the offending, powder-dry branches are exploding against the tarmac, where Randy shoves them aside to make way for possible saviors.

The breeze has shifted into the west. Tiny bits of ash alight on car hoods and the lenses of my sunglasses. The odd, unsettling sense of isolation seems inevitable. But meanwhile, trenching is in order—around the main house, the garage, and the two well houses. The implement used for this, the McLeod, is a heavy hand tool with two working edges: a broad, hoelike blade and a fanged rake. Randy quickly moves earth and needles into rows, creating more firebreaks, while I sweep leaves from low roofs. Soil, systematically exposed in neat circumferential alleys, must be hosed down.

But most of the hoses are in the big cave next to the winery, a collection of eight stainless-steel fermenters under arching metal girders, open to the sky. A great rolled sailcloth can be stretched overhead if the sun becomes intolerable, but before the harvest, the sail stays furled. The grape press is parked to one side of the crush pad, and that’s it but for heavy oak doors under a concrete archway that lead to the cave, a world unto itself.

Fifty-odd gallons of Dunn petite syrah, a hobby pressing that comes before the main event each year and is intended for family and friends only, bubbles in a smallish metal tank on the crush pad. A square of cloth has been duct-taped over the top, to keep the wasps out. Randy interrupts his labors and says, as he stands on an empty beer keg, “Let’s make some wine.” Using a special steel implement with a canted blade, he punches down the clot of purple skins floating on top, a practical step in winemaking that is thousands of years in practice and increases a wine’s color and intensity.

At that moment, a sheriff’s cruiser pulls up, having passed both the paddock and the house without slackening speed. A deputy gets out in a drift of dust, his belt weighted with a capable-looking automatic pistol and handcuffs. Randy gets down to talk to him, providing, when asked, his name and those of the surrounding neighbors, all of which the deputy dutifully enters into a spiral notebook. When they’re done, the deputy says, “White Cottage Road’s being evacuated,” for the second time in 14 hours.

Randy says, “Okay.”

“Are you leaving?”

“Maybe.”

“That a yes, or a no?”

There’s a pause. “No,” says Randy, and the deputy and his partner pull away, leaving a skein of new dust. They’re too busy to bother with a recalcitrant property owner, though they’re unlikely to forget him.

Randy pulls open the doors to the cave. The dim space is punctuated by winking lamps tunneling toward the heart of Howell Mountain, the corridor lined by French oak barrels like opposing sentinels forming a blond, symmetrical honor guard. He makes his way toward the farthest barrel, collecting a hose here, a hose there. Draped with heavy rubber coils, he ascends to the buildings above and attaches nozzles that can be directed toward embers or creeping ground fire during that short interval when a fire is possibly controllable.

More water will be needed for an inferno, however—more than is readily imaginable. Thirty feet from where that mountain lion once jumped through the window stands a faded red International fire engine built in 1946 by Van Pelt of Oakdale, California. It’s an elegant conglomeration of red domed lights, old cloth hoses folded and stacked like 100-foot pythons, rubber hoses on hand-rolled wheels, spiderweb-covered railings, and various other accoutrements out of a Buster Keaton film. Most important, though, the antique fire engine has an 800-gallon water tank, which Randy now fills, using a big plastic pipe from the well’s concrete collecting tank.

Randy bought the engine as is from Mike Robbins, the owner of Spring Mountain Vineyard—also known as Falcon Crest on the 1980s television show—when Robbins, despite the success of the soap opera, was in bankruptcy. The fire engine’s transmission was jammed, and Robbins agreed to take just $1,500 for this classic, even on the off chance that Randy could get it running. So Randy borrowed a crowbar, fixed the transmission in a few minutes, and hauled the fire engine up Howell Mountain on the trailer. He parked it in the field south of the house, where it has sat ever since.

When Randy presses the ignition switch, a blast of black smoke erupts before the motor turns over with authority, filling the afternoon with the resonance of old-time, unmuffled vehicles.

We pull the flat cloth hose onto the grass, up the stairs, and across the office porch, where Antonio Galloni will have to step over it the next morning—if there is still a winery here and cabernet to taste. The hose expands as the engine pumps water through it. For one frightening moment, the nozzle—sculpted brass, a work of art in its own right—blasts a barely manageable torrent as thick as a man’s arm before the motor is shut off.

Fortunately, the smaller rubber hoses emit streams of water less likely to break windows. Their pump runs off the main engine, and Randy gets it running, too. The rubber coils throb as they come off the roller. Pull the trigger on a fancy nozzle, and a shaft of water shoots half the height of a Doug fir. The fire engine’s water tank is full, the hoses are ready, and Randy shuts everything off.

It’s late afternoon, and there’s no sound now from the one house visible to the north, no sign of human life in the encircling view. The breeze is undetectable in the trees, but high overhead, curdled clouds move glacially out of the south. Randy walks around the paddock and down to the pond, where a child’s plastic paddleboat sits among the weeds.

He pushes the two-person boat into the water, then climbs in alone and tests the paddles. The boat lists to one side, so the paddles make it go round in a circle. Randy climbs out and wades in deeper. Here we could stand and possibly survive, although it would be a very long night. We would watch the firs crown out in paroxysms of flame, the Dunns’ house following. We would listen to bottles exploding in the cellar, hot embers raining all around as we felt the pressure of lung-collapsing heat. If we had fire suits and gas masks, though, we could contemplate the smoke through a thin sheet of scuffed plastic. But Randy says ruefully: “I’ve only got one gas mask.”

At dusk we go into the kitchen, where Randy makes margaritas with a single-field tequila called Ocho, for which he trades Dunn Howell Mountain cabernet. This sort of bartering—cab for a case of tequila, cab for a flat of apricots, cab for a reworked airplane part—is as old as agriculture. Meanwhile, I cook hamburgers doused in Worcestershire sauce, and then we devour them, Randy drinking a bottle of Sierra Nevada pale ale and I a glass of a previous year’s Dunn petite syrah from one of the open bottles next to the sink.

All outside lights are off now, and darkness settles in like a sentence. The thought of dying from smoke inhalation at two in the morning recurs, but Randy has been through this before; he’s no fool. And if I stay, I can have another glass of petite syrah.

A friend calls from St. Helena: rumor has it the National Guard is coming to evacuate any stragglers. Randy hangs up. “If we see anybody in the road,” he says, “we’ll just turn off the kitchen light.”

After dinner, he turns off the light anyway and goes back outside, where he puts on his headlamp. Exhausted, I head for the guest bedroom, where there’s a shower and double glass doors to stop any mountain lion. It occurs to me as I pick my way through the darkness that, in this age of calamity, falling embers are a metaphor for a host of real possibilities. We’re all waiting for fire now.

The last time I see Randy that night, he’s back up at the well house. If the National Guard comes, they will see a bobbing circle of yellow light and hear the sound of someone wielding a McLeod, working.