People sometimes think that I bring home all these old books because I’m addicted, that I’m no better than a hoarder with a houseful of crumbling newspapers. There may be a little truth in this view, one sometimes enunciated by my Beloved Spouse when she’s feeling less than pleased with me. Moreover, I do drop by the special biblioholics meeting whenever I attend Readercon, a science fiction convention for people smitten with print.

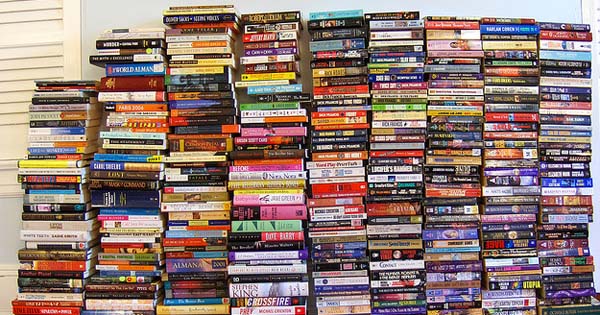

But the deeper truth of the matter is somewhat different. All these ziggurats of books in the bedroom and on the attic steps and on top of the piano are future projects, awaiting that time when the stars are finally right. Then great Cthulhu will rise … No, that’s something else that happens when the stars are right. As I was about to say, each stack will sooner or later be transformed into an essay, article, or long review.

For instance, just behind me are a half dozen books by or about Julian Maclaren-Ross, a hard-drinking, raffish bohemian of postwar London who wrote comic novels (Of Love and Hunger is about a vacuum cleaner salesman), parodies, short stories, and a volume of reminiscences titled Memoirs of the Forties. Paul Willetts helped bring his work back into print through a biography—Fear and Loathing in Fitzrovia—and new editions of the principal works. Maclaren-Ross is, by the way, a model for X. Trapnel in Anthony Powell’s 12-part A Dance to the Music of Time.

Who are some of the other authors I long to write about? Well, on the landing in the attic sits a box of the Chicago bookman Vincent Starrett’s fiction and nonfiction, both waiting for my attention. I even owe the Battered Silicon Dispatch Box—a Canadian publisher—an introduction to Starrett’s Born in a Bookshop. I’ve somehow accumulated all of Elizabeth Taylor’s novels, as well as Nicola Beauman’s biography, and one day would like to read them. All I know is that Taylor is frequently likened to Barbara Pym, which is good enough recommendation for me. A couple of years back I enjoyed Sylvia Townsend Warner’s correspondence with her New Yorker editor, William Maxwell, and now I seem to own a dozen of her books and feel, quite sheepishly, that I should have started on Lolly Willowes and Mr. Fortune’s Maggot long ago.

Then there’s Gerald Kersh, a versatile novelist still known for Night and the City, but whose macabre short stories, such as “Men Without Bones” and “The Queen of Pig Island,” are horrifically unforgettable. I’ve found good copies of Fowlers End and several of his other works. A step down in literary quality, but a step up in one-time popularity is Dennis Wheatley. Wheatley’s thrillers featured aristocratic good guys in battle with Satanic forces, those forces generally seeking to use beautiful young women in Black Masses or other hideous rituals. His most famous book is The Devil Rides Out, closely followed by To the Devil—a Daughter. Great stuff—plus there’s a terrific biography of the man himself by Phil Baker.

Is that all? By no means. That wisest of all science fiction writers, Barry Malzberg, recently suggested that I return to the work of Walter Tevis, whose two most celebrated novels became even more celebrated movies: The Hustler and The Man Who Fell to Earth. My friend the late Tom Disch once told me that Tevis’s The Queen’s Gambit—about an abused girl who discovers a profound gift for chess—was the best book he’d ever read about what it must feel like to be a genius.

As you can tell, I do like to listen to my friends and follow their advice. Brian Taves, an authority on early film, P. G. Wodehouse, and Jules Verne, is also an expert on the adventure novels of Talbot Mundy. He generously gave me a few reprints, and I’ve now bought several more, most recently an old first of The Nine Unknown. One day I will sit down and read Om: The Secret of Ahbor Valley, King of the Khyber Rifles, Jimgrim, The Nine Unknown, and, maybe even the massive Tros of Samothrace.

We’re not done yet, far from it. I own the four thrillers by Clayton Rawson about the magician-detective The Great Merlini, including Death from a Top Hat and The Footsteps on the Ceiling. I’m already a fan of the locked-room howdunits of Rawson’s friend John Dickson Carr, and my favorite mystery subgenre has long been the impossible crime. Of course, it’s but the tiniest of steps from the seemingly impossible to the genuinely supernatural, so I am also fond of psychic detectives and keep meaning to reread, and write something about, William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki, The Ghost Finder, Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence stories, Kate and Hesketh Prichard’s The Experiences of Flaxman Low, and, to include a contemporary example, The Collected Connoisseur, by Mark Valentine and John Howard.

But looking further around the house, I notice all these books by Freya Stark and Lesley Blanch about travels and adventures in the Middle East. I’ve got half a bookcase devoted to classic accounts of famous murders and notable British and American trials, including F. Tennyson Jesse on Madeleine Smith, Edmund Pearson on Lizzie Borden, William Roughead on Oscar Slater and many others—as well as four or five books by Rayner Heppenstall on the famous criminals of France. Last year David Bellos—biographer and translator of Georges Perec—sent me a copy of his life of Romain Gary, after which I began to pick up the novels of this former husband of both Lesley Blanch and actress Jean Seberg. One of these days I aim to set down my thoughts about time-travel stories, so I own seven or eight collections of these. Having serendipitously found a box of Dornford Yates’s clubman adventures at a yard sale, I eagerly await the right holiday to enjoy Berry and Co., Jonah and Co., Perishable Goods, and perhaps a few others. Oh yes, and I’ve also promised myself to read more of the works of Shakespeare’s great contemporary Ben Jonson.

Above all, though, I’ve accumulated lots of popular fiction from the period between 1875 and 1930. I still occasionally mull over my proposed project for a massive study called “The Great Age of Storytelling.” So there are short story collections here by Gerald Bullett, Marjorie Bowen, and Martin Armstrong, lost-race novels such as Cutcliffe Hyne’s The Lost Continent, the principal swashbucklers of Stanley Weyman. And so much more. Much, much more.

Sigh. Perhaps my Beloved Spouse is right. While there’s definitely method to my madness, it may well be madness nonetheless.