I spent the summer solstice in England, where the sun rose at 4:43 and more than 20,000 druids, pagans, and other revelers descended upon a rain-sodden Stonehenge to drink, beat drums, declare eternal love, and proclaim their unity with the sun. The ancient circle of standing stones, which dates back more than 5,000 years,may once have been the site of sun worship ceremonies that predate the erection of the monumental ring, as well as one of the earliest attempts to study the sun’s movement. Six days after the solstice, on June 27, NASA launched a satellite that will scan the part of the sun—between the surface and the corona—that remains mysterious to modern sun worshippers and everyone else. It is the middle chromosphere, a layer where temperatures soar from 6,000 degrees Kelvin at the surface of the sun to more than one million degrees in the corona, the outer atmosphere.

Named the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph, or IRIS, the $181 million telescope will fly in a sun-synchronous polar orbit—passing over both of Earth’s poles in each revolution—training its ultraviolet “eyes” on a tiny patch of the chromosphere. In that mysterious layer, which is some 1,700 kilometers thick, a strange and anomalous transformation takes place. Usually, the closer you move toward a heat source, such as a fire, the more heat you feel. But the solar atmosphere gets hotter and hotter as it progresses farther away from the sun. Most of the heating takes place in the chromosphere and in the transition region just below the corona.

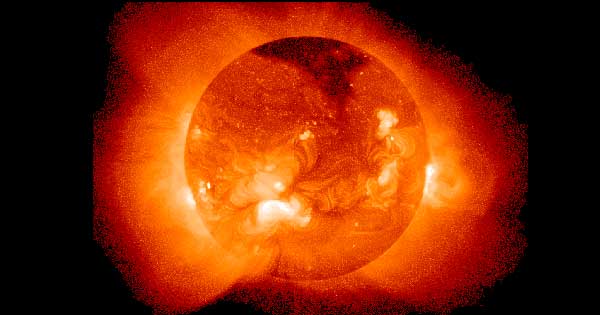

The chromosphere is a roiling mass of ceaselessly mixing hot and cold plasma, where tendril-like jets funnel mass and energy away from the surface of the sun. IRIS’s finely tuned “eyes” will enable astronomers to track these plumes as they travel through the chromosphere, helping NASA scientists to understand how the plumes gather energy. Such information can help explain the cause of explosive coronal mass ejections and other forms of space weather that travel toward Earth and can disrupt human technology.

Such disruptions may be of little concern to the carousers at Stonehenge, who had gathered to honor “our relationship with the earth and with the sky,” according to Frank Somers of Amesbury and Stonehenge Druids. But they affect our lives in myriad ways. “Auroras, power outages, loss of GPS signals, and radio blackouts are some of the manifestations of space weather that we experience on Earth,” says Jeff Newmark, Heliophysics Explorer Program scientist at NASA. Such massive events “start as interactions on the smallest scales, motions deep within the solar atmosphere,” he says. “IRIS will help unlock these mysteries, eventually allowing us to mitigate the perils of space weather.”