We Must All Become Yogis

An ancient Hindu text offers advice on how to remain sane in uncertain times

When I demand that he leave his bedroom and turn off his devices, my 14-year-old son mutters that he hates me. I know he doesn’t mean it. I Covid his words just as I have had to Covid my students’ grades this semester or Covid a recipe for oatmeal cookies realizing too late that I forgot to add butter to the grocery pick-up. I Covid a lot these days, extending deadlines and generosities as I try to ensure that those around me are okay. Still, at night I writhe with uncertainty. I cannot Covid my fear.

In Hindu scripture, the second chapter of the gita provides one of the first known definitions of yoga. Here we read that a person “established in yoga” performs action without attachment “while remaining the same in success and no success.” And that “such sameness is yoga.” Westerners tend to think of a yogi as someone who contorts their Lululemon-clad body into poses that resemble modern art, but the Gita defines a yogi as one who remains still in the sea of change. The Sanskrit seems important here. The verse ends samatvam yoga—sama meaning the same, and tvam meaning you. In yoga, you remain the same. Or more precisely, yoga is the ability to maintain equanimity even when your son says he hates you, your university makes plans to be mostly online in the fall, and movie theaters begin re-opening while death rates are still rising. You remain the same.

I am a yoga teacher and 20-year practitioner. Accepting and sitting quietly with uncertainty should be my bread and butter. This is, after all, why we practice: so we can take refuge in the present moment rather than be held in thrall to the past or the future. More than most, perhaps, a yogi should ride the pandemic like a breath, lifting on the inhale and surrendering on the exhale. Yet I writhe.

Gandhi said that the Gita was the most important book he had read: “When doubts haunt me and disappointments stare me in the face and I see not one ray of hope on the horizon, I turn to the Bhagavad Gita and find a verse to comfort me; I immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming sorrow.” Given the world in which we find ourselves, the Gita seems like the perfect pandemic text—not because it offers clear and easy answers, but because it teaches surrender when confronted by a colonial government, or an invisible virus that turns our bodies into weapons.

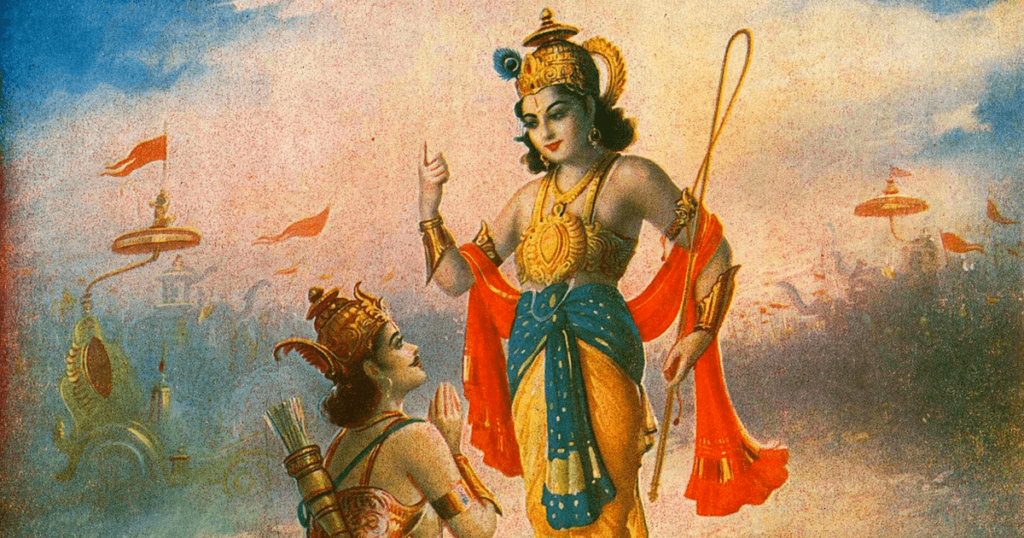

The Gita begins in turmoil. Its hero, Arjuna, a member of the warrior class, faces combat. Members of his family stand armored on either side of the battlefield, so his only choice, it appears, will be to kill kin. He turns to his charioteer—the god Krishna in disguise—and asks for advice. What follows is not a battle plan so much as a love letter to the world. Yoga scholar Seth Powell says that one of the central messages of the Gita is that “we must transform a painful world into a meaningful one.” Importantly that transformation requires action. You cannot simply choose not to engage, for even that is an action. Arjuna must do his duty, follow his dharma. He must fight. What Krishna teaches the young Arjuna, though, is that we should act out of love and then release our attachment to the outcome. As yogis, we remain the same no matter what ensues.

I have been keeping a pandemic journal for 52 days, throughout which my constant refrain has been, “I don’t know.” Uncertainty marks my pages, just as it arises in disturbing dreams at night. Uncertainty causes me to lose patience with my sons, buy 12 cans of tomato soup, and attend Zoom meetings with friends I haven’t seen in 30 years. I am far from surrender. Instead, I clench, literally holding onto a carton of toilet paper like a life raft.

At the beginning of the Gita, Arujna takes a seat on the chariot “in the middle of the battlefield” and remains there for the next 17 chapters. Again, it is not that he doesn’t act; his action is to become still, to watch and listen. Arjuna’s decision to remain in the middle of the battlefield reminds me of the action Gautama Buddha takes on the night of his enlightenment. As Mara, the demon, casts arrows of anger and jealousy, as he disparages and mocks, the Buddha puts his right hand to the ground and reminds himself of where he sits. The earth responds, “I am your witness.”

To still our bodies, to be in touch with the ground beneath us: these ancient stories suggest that such actions lead to calm and certainty. One of the many ironies of the pandemic is the way it has intensified our awareness of how little control we have over the future. It has intensified our awareness; it has not created uncertainty. In our pre-pandemic world, we reassured ourselves with the story that we were in control. The pandemic refutes such blindness. Change is the constant. We cannot weave a different story now. Instead, we must all become yogis.

My son says he hates me as I stand underneath the ash tree in our back yard. In May, the leaves are only now appearing, lotus-shaped bundles at the end of each branch, lit by the morning sun, tree turned into candelabra. My back rests against the wooden Adirondack chair, and I think back to the days when my son was two. Faced with change or disruption, he would softly knock his forehead on the ground in frustration. Twelve years later, he can articulate loss. I have to listen closely, though, and translate the words. I must pause and attend. From my seat beneath the ash, “I hate you” becomes “I am tired of living like this and desperately want to return to how things were.” From my seat beneath the ash, “I hate you” becomes “Will you hold me and tell me that everything is going to be okay?” When I am able to still my body and really listen, then the only possible action I can see is to move toward him while the Earth spins beneath my feet, the ash grows toward the light, and the virus spirals through the air. I leave my seat to find my son, invested in the action but surrendering the results.