His name wasn’t Joe Strummer. He didn’t strum his guitar, either; he famously hammered down on the strings, thrashing them so hard and fast that the fingers of his right hand were in tatters after a show. His name was John Mellor. He was born in Turkey, of a mother born in Scotland and a father born in India, and he lived in Egypt and Mexico and Germany before being sent to boarding school in Surrey at the age of nine. He said he never recovered from being exiled to that prison filled with violence and cruelty, where he made himself a jester, a scamp, a leader of the mischievous, neither scholar nor dolt nor leader nor Lothario but a boy apart, one who knew how to escape the castle but avoid substantive punishment, who procured forbidden food and music, who bartered and fidgeted and gambled while others studied or starred on the playing fields.

At the age of 16, John Mellor was called into London by the Metropolitan Police Service to identify the body of his brother, David, who had been found dead in Regent’s Park. David was John’s only brother, just 18 years old. The brothers had no sisters. Their parents were in Iran or Africa at the time. (Imagine being 16 and seeing the body of your only brother.) He had died by a lake—water and waters were holy and powerful for him. In later years, when John Mellor was Joe Strummer and at peace with himself after many battles, his favorite thing to do was to make bonfires near rivers and sit with friends and passersby and share stories and songs. He especially liked going to outdoor festivals and wandering from bonfire to bonfire at night, carrying children on his shoulders, just a friendly man with a cowboy hat, and not Joe Strummer.

He died on his couch, in the village of Broomfield in the shire of Somerset, just after three in the afternoon. It was Sunday, a few days before Christmas, 2002. He had been up all night choosing the order of songs for a record release. He slept in late and rose at lunchtime and made tea and took his three dogs for a walk and settled on the couch to read The Observer. The Observer is the oldest Sunday newspaper in England, its office near the River Thames. Sometimes the Thames is still called the Isis or the London River. Joe lived in eight places near the Isis River, including Wood Green, which is near the River Lee, and Willesden, which gave its name to the most gentle beautiful musing alluring meditative song he ever wrote. He wrote it three years before he died. One of his bandmates said later that he thought it was the first song John Mellor wrote after being Joe Strummer for half his life. Some people think that “Willesden to Cricklewood” is about Joe Strummer walking through his neighborhood on the way to buy drugs. Not me. I think he was walking through a neighborhood he loved, a neighborhood in which he knew shops and pubs and restaurants and grocers and the men and women who ran them (Crossing all the great divides / Color, age, and heavy vibes), a neighborhood where people knew him and said, Hey Joe! and didn’t want anything from him other than his smile, and he had an epiphanic vision of the intricate webbing that binds us all, everything and everyone touching and being touched, cousins and companions in this wild life. I think the song is about one of the happiest moments in John Mellor’s life. I think he had a vision of love and joy and peace and laughter, and after that, he did what he did best: he wrote a song.

His wife, Lucinda, found him when she came home at four. She had been out shopping for Christmas dinner. The three dogs had “obviously had a good walk,” she said. Joe looked like he was asleep on the couch, she said—he had been very sleepy the last few days. She tried to wake him. He was cold in places, she said. She tried to resurrect him by breathing into his mouth. A nurse visiting a neighbor came running when she heard Lucinda’s screams, but she could not resuscitate him either. I could tell that he was gone when I saw the look on her face, Lucinda said. He was 50 years old. At his funeral a week later, ranks of firemen came, in full dress; he had played a benefit show for striking firemen in Acton. Acton is famed for the waters of its natural springs and is the birthplace of the Who, most of whose members attended Acton County Grammar School until they became, in order, the Confederates, the Detours, the High Numbers, the Hair, and finally the Who.

John Mellor’s coffin was accompanied by bagpipers. His coffin was adorned with a cowboy hat and stickers reading question authority and musicians can’t dance. Five songs were played at his funeral, four of them from a boom box covered with roses. The bagpipers performed the first, the haunting Scottish lament “Chì mi na mòrbheanna,” written in 1856 by a quarryman and farmer named Iain Òg Ruaidh, from the village of Baile a’ Chaolais, near the River Laroch. The second was one Joe Strummer wrote and recorded with the band that was the most famous band in the world for a while. The third, a slow blues number, came from a demo tape he had made. The fourth song was “Willesden to Cricklewood.” The last song, a hit for the American actor Lee Marvin in 1970, was “Wand’rin’ Star,” played as the mourners left the crematorium, many of them pausing to touch or speak to the gathering of atoms that had once been John Mellor. When I get to heaven, tie me to a tree / For I’ll begin to roam and soon you’ll know where I will be …

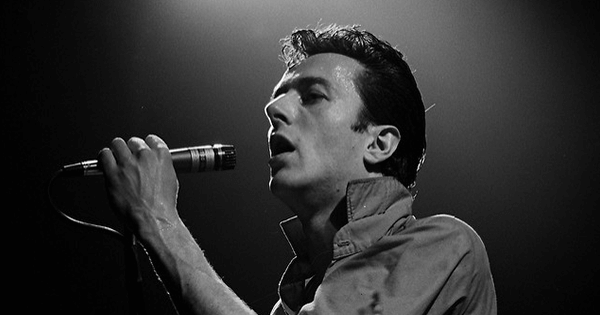

The most famous band in the world for a while—“the only band that matters” was their record producer’s marketing slogan—was born on May 31, 1976, in the Shepherd’s Bush section of West London. The man who had been John Mellor, and who had now been Joe Strummer for a year, sat down in a tiny second-floor room with two guitarists. One of them could play beautifully. The other could not play at all. By the end of an hour, they had tinkered with three songs and concluded that Joe Strummer would teach Paul Simonon how to play the bass sufficiently well for the songs that Joe and Mick Jones would write, and that Jones, the terrific guitarist, would play lead, and that Strummer, who had never had a music lesson in his life, whose first instrument was the drums, who had already changed his name twice, who had been asked to identify his brother’s crumpled body, would play rhythm guitar and sing. A while later they found their drummer, who had been playing in a band called Fury and been fired from Fury for not hitting hard enough, so when he got a chance to play with this new band, he hit with all his might. Thus Nicky Headon, nicknamed Topper, joined the band.

On July 4, they played their first public show, in a pub called the Black Swan in Sheffield. In August they were back in London, playing in Islington and then on Oxford Street, beneath which runs the River Tyburn. In December, they went on tour for the first time, opening for a band that had variously been called the Strand, the Swankers, the Subterraneans, and Teenage Novel before settling on the name the Sex Pistols.

In January, they signed a contract with a record company for £100,000—just shy of a million dollars in today’s currency. In the next five years, they would sell about 100 million records, before their affections and energies flowed in four different directions.

For a while, Joe Strummer and his new companions called themselves the Heartdrops, and then they tried the Psychotic Negatives, but finally they settled on a name hatched by the bass player, who said he kept noticing one word above all other words in the newspapers every day, so they adopted that word as their name, and they became the Clash, of which much has been written; well, some of it was true, as their song “London Calling” has it—lyrics by Joe Strummer.

Johnny Mellor’s last day as a child may be said to have been early in September of 1961. He had just turned nine years old. He and David were sent to boarding school in Ashtead Park, in Surrey, even though their parents lived only 20 miles away. The school was founded to educate orphans. Johnny Mellor later said many times he felt that he and his brother were abandoned by their parents in 1961. Johnny Mellor spent the next nine years at that school. On his first day, wearing a blue school jacket and a school tie and a blue school cap, he was beaten by the older boys with a wooden coat hanger. The youngest boys were referred to as grubs. But they were allowed to listen to the radio (Radio Luxembourg and Radio Caroline, the pirate station broadcast from an ocean freighter anchored three miles off the estuary of the River Orwell, the river for which Eric Blair changed his name to George Orwell), and that is where Johnny Mellor first heard the Beatles and the Stones and the Kinks and the Yardbirds and the Beach Boys. “I can’t imagine how we would’ve got through being at that school without … that rock explosion,” said Joe Strummer years later. “I don’t think we would have been able to stand it. It just got us through. … We couldn’t have survived without that music.”

During school recesses, the brothers would visit their parents in Iran or Malawi and then be sent back to the school both of them hated with all their might. Johnny Mellor survived. He played rugby and became the school’s cross-country champion. He sang in the choir, was a favorite of the art teacher. He was not a favorite of any other teacher, and upon failing what would be the American equivalent of his high school junior year, he had to repeat his classes. He acted in school plays. The parents of all boys acting in school plays were invited to public performances in the town of Ashtead. Johnny Mellor’s parents never came.

In his final year at the Orphan School, Johnny Mellor adopted the name Woody and refused to answer to John or Johnny anymore. David graduated and moved to London and joined the neo-Nazi National Front party and hung posters of Adolf Hitler in his room. Woody Mellor published a quatrain in the school poetry magazine: And the pebbles fight each other as rocks / And my father bends among them / Two hands oustretching shouting up to me / Not that I can hear. In July of 1970, the body of David Mellor was found in Regent’s Park, on a bench on the tiny island in the boating lake. David’s death was deemed a suicide by aspirin poisoning. His body had lain undiscovered for three days before the police found it and tracked John down to identify what had once been his only brother, the brother who had essentially been his twin for their first nine years together, the brother who hardly spoke, now a decaying corpse. Some 20 people went to the funeral, including the three remaining members of the Mellor family. John Mellor took possession of his brother’s suicide note and held on to it the rest of his life. Two weeks later, Woody Mellor and a friend went on a camping trip by the sea, where the ocean welcomes the River Ouse. The River Ouse is famous for having drowned the writer Virginia Woolf. One day in 1941, she filled her overcoat pockets with stones and walked into the river. Her body was undiscovered for 20 days. “Dearest, I feel certain that I am going mad again,” she wrote, in a note she left for her husband. “I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. … I can’t fight any longer.”

The last day of the Clash might have been May 21, 1982, the day three of the members of the band fired the fourth one for being a heroin addict. This was Topper Headon, the drummer, who the rest of the band felt could not be trusted to show up for rehearsals, shows, interviews, airplanes, and all the rest of the business of being the most famous band in the world. That three band members who greatly enjoyed marijuana, cocaine, beer, liquor, and liqueur would fire the fourth for indulging in drugs bore a certain irony, but they did just that. A little more than a year later, two members of the original band fired the third remaining member, the terrific guitarist Mick Jones. Two years later, the two remaining members decided that the Clash as they had envisioned it was finished, despite their manager’s furious attempts to keep the name going with new musicians, and the Clash was no more. Joe Strummer, weary of being Joe Strummer, ashamed that he had played a part in firing his friend Mick Jones from the band, rattled at the death of his father and fearful of the imminent death of his mother, growing apart from his partner, Gaby, desperate to disappear somewhere despite the fact that he had a new daughter in England, went to Spain.

So began his wilderness years—“the days of treacle,” as he said himself. For a good part of the 1980s and ’90s, he grieved, he drank, he occasionally acted in films, he welcomed a second daughter, he drank, he married Lucinda Tait, he occasionally helped out producing records for friends, he traveled alone, he drank, he occasionally wrote and recorded a song for friends’ projects, he drank, he went for long walks with his dogs, he occasionally sat in with bands he admired, like the Pogues, he ran the Paris marathon without training for it, he drank, he started doing an eclectic weekly radio show for the BBC, and he began to be obsessed with campfires and bonfires around which he would sit drinking and talking and singing with anyone and everyone for days at a time, either at outdoor festivals like Glastonbury or on the land he rented in Hampshire, or the land he bought in Somerset, or the land he bought in San Jose, Spain. He made fires everywhere, especially when he was sad or weary or muddled. He made them in his yard, in fields and meadows at festivals, on the beach in Spain, and his wife and his friends say that he was never so happy, never so at peace, never so much himself, perhaps never so much Joe as John, as he was sitting around a roaring fire and drinking and talking and singing and going for more wood to keep the fire and the moment going. Nothing was as anciently and unadornedly human, he thought; nothing was so uncomplicatedly communal, without all the usual trappings of power and status and money and politics and greed and violence and pain and loss.

The first day Joe Strummer started to not be Joe Strummer anymore was perhaps June 5, 1999, when he and a group of friends played a show in Sheffield—the same city where the Clash had played its very first show, near the Rivers Sheaf and Don. The first name suggested for the new band was the Hand of God, and the second was Longbow, and the third and final was the Mescaleros. The next day they played a show in Liverpool, and then they played in Glasgow, and then Portsmouth, and then they were off and running, a tight relaxed easy loose wild jazzy reggae rock ska band with African rhythms and soon a violinist, a band that occasionally played Clash songs in their live sets if Joe was in the mood. Holland, France, Belgium, Germany, Sweden, Finland, the United States, Japan, England, New Zealand, Ireland, and on and on for the next three years, the Mescaleros—the Young Guys—were instantly good and soon almost famous. They played old Irish tunes, they played old reggae, they played new songs Joe wrote at a fever pitch. They argued and bickered and drank and fired a member. They played a show in New York City on October 3, 2001, three weeks after September 11, because Joe refused to cancel it and said they would do it for the firefighters of New York City. In August of 2002, he celebrated his 50th birthday on the beach in Spain with his daughters and his wife and his friends. The night after his birthday, he and his friends built a fire on the beach at midnight and stayed up until dawn playing music and telling stories.

The last day Joe Strummer was Joe Strummer might have been November 15, 2002, when he and the Mescaleros took the stage at the Acton Town Hall. This was the benefit for the men of the Fire Brigades Union, who were on strike and had asked Joe Strummer for help. Of the 16 songs the band played that night, eight were Clash songs. After the second song Joe announced from the stage that “Mick Jones is here tonight! And more than that, Mick Jones and his lady Miranda have had a baby last Sunday morning. And the baby’s called Stella. And this is going out to Stella.” And the band charged into the Clash reggae song “Rudie Can’t Fail.”

Jones had no intention of leaving the audience that evening. But soon after he heard the first notes of “Bankrobber,” he was heading up on stage. There is a grainy video of this moment, as the band begins the swaying rhythms of the song Joe Strummer had written with Mick Jones when they were in their 20s in the most famous band in the world for a time, and though you cannot see Jones pick up a loose guitar at the side of the stage and grin at his friend, you can see Strummer, intent on his instrument, look up and smile broadly and point with delight and shout, All right, baby, play that guitar now!

There was a brief pause after “Bankrobber.” In the video, you can hear Strummer shout to Jones, “In the key of A! You know what! Let it burn!” And as they began “White Riot,” another song they had written together for the Clash, the stage and the hall and the moment and the crowd exploded. In the middle of the song, Jones took a solo, and there’s just enough light, in the murky film, to see the two friends laughing with pleasure. Then they played yet another song they’d written together with the Clash, “London’s Burning,” and that was the end of the show. Mick Jones took a cab home to his wife and new baby, and Joe and the band wrapped up a few small shows before a break for Christmas. On December 20, by happy chance, Mick and Miranda walked into a London pub for a late drink and found Joe and Lucinda. Two days later, John Mellor got up late and made tea and walked the dogs and sat down on the couch and his heart stopped.

When a man dies, and is cremated, and his ashes are given to the sea, some of his molecular and atomic integrity remains “extant,” as biologists say carefully—which is to say that many of the atoms of which he was composed do not dissolve, but rather enter other forms and beings. In the case of John Mellor, let us say, whose ashes were loosed into the Alboran Sea in Spain by his two daughters on what would have been their father’s 51st birthday, many of the atoms of which he had been composed entered the ocean, and subsequently entered swordfish and storks and shearwaters and sardines. Some of what had been John Mellor entered children playing along the shore in Spain and Africa, and some entered men and women playing guitars at night by bonfires on the beach. Some of him was carried by the current through the Pillars of Hercules into the ocean that was once called the Sea of Atlas and the Ethiopic Ocean. Some of him entered fish that entered people, one of whom may be you.

So it was that the man who was John and then Woody and then Joe and then finally perhaps John again, the man whose life had been watered by music and muddle and tears and beer, the man whose brother had died by a lake, the man who loved roaring fires and waters, the man whose final house sat on the bank of a river he could hear humming all day and all night, the man of celebrated natural springs of open charm and hidden pain, was himself carried by water into the myriad songs of other beings. Some of what was John Mellor perhaps became trees that became guitars, or hops that became ales, or maybe larynxes in singers; some perhaps became auditory nerves in people who listen to his music and remember him with affection and are moved still by the songs he wrote, thrashing to connect to the brothers and sisters he did not have, to the brother he lost, to the small boy abandoned by his parents and sent to a sort of prison by the River Mole.

Some of what he was is on flickering film and some is in recorded music and some is in his drawings and scrawled lyrics and the sweat and spit worked into the wood and plastic of his guitars. Some is story and some is memory, some the bonfires lit around the world every December 22, as people gather on hilltops and beaches, in fields and meadows, to remember the man who was John and Woody and Joe and finally maybe John again, an unadorned unadvertised uncommercial communal honor he would have most enjoyed. With hard work and great luck and deft cruelty, you can always achieve mere fame; but it is something else that breeds affectionate memory years after your death, on hilltops and beaches and meadows around the world.