On a cool, early summer evening in June 2015, I was at the Friars Club in midtown Manhattan to celebrate my friend Talia Carner’s new novel, Hotel Moscow. I started talking with Talia’s husband, Ron Carner, and we quickly realized that we’d gone to rival Brooklyn public high schools—he to James Madison and I to Erasmus—and as soon as we discovered our mutual love of basketball, we did what aging Brooklyn hoop junkies usually do when they get together: we exchanged tales of local ballplayers we’d seen and played against—All-City and All-American players who had gone on to celebrated college and pro careers. And when we started naming players from our schools who played in the NBA—Rudy LaRusso from Madison, Billy Cunningham and Doug Moe from Erasmus—Ron stopped suddenly and asked if I’d ever seen Frankie King play.

“See him play?” I said. “He was the most exciting ballplayer I ever saw back then.” I added that I could still picture him clearly: a lefty, a shade under six feet tall. When he drove to the basket, nobody could stop him.

Ron said he was asking if I’d seen Frankie King play because King had passed away only a few weeks before—his family had placed an obituary in The New York Times. “For more than half a century,” Ron said, “we’ve all been wondering what happened to him, because Frankie just seemed to have fallen off the face of the earth.”

King had gone to Madison, and at the age of 15, he became the youngest player ever to make first-team All-City—and this at a time when New York, and Brooklyn in particular, was the basketball capital of the world. In those days, sportswriters were comparing King to some of the greatest college and pro players of all time, and every college in the country had been after him. The University of North Carolina recruited him to be a starting guard on a team that would eventually beat Wilt Chamberlain’s Kansas Jayhawks for the national championship. “But Frankie left North Carolina after only a few days—he never played a game,” Ron said. “The last I’d heard—this goes back a few years—somebody spotted him panhandling on the Bowery. Other guys told me they heard he’d enlisted in the Army, was put in the stockade, tried to escape, and was shot and killed. There were also rumors that he’d shot an M.P., and that he’d been Jimmy Hoffa’s bodyguard and was buried with Hoffa. And some guys heard that he’d been an enforcer for John Gotti.” In recent days, Ron and his friends had been calling one another, astonished to learn the truth: that for the past 60 years, Frankie King had been in New York, hiding out in plain sight.

Later that night, I found the Times obituary and learned something even more astonishing: King had been the author of more than 40 novels. That one of the greatest ballplayers of my generation had also been a prolific novelist sent me tumbling back to the years following World War II when the two great passions of my life were novels and sports. When I was nine years old, I wrote a 60-page novel that my mother typed out for me, and I would read it aloud, chapter by chapter, to my fourth-grade class at P.S. 246. When I wasn’t reading or writing stories, I was playing ball in schoolyards and gyms. I lived within a few blocks of Ebbets Field, and I got to see my heroes—Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese chief among them—play several times a year. There was a welcome place in my heart for the likes of “Sweetwater” Clifton, Buddy Young, Benny Leonard, Hank Greenberg, and Joe Louis, athletes who were either Black or Jewish. To be a member of a race or religion discriminated against in often lethal ways, and to see athletes celebrated beyond the poor and lower-middle-class neighborhoods in which we grew up, was to have had our dream come true, and also—a driving force for those of us one generation removed from the shtetls of Eastern Europe, or the racially segregated towns and cities of the American South—to have become, somehow, Americans.

Most of the books King published were under the pseudonym of a woman, Lydia Adamson, but his first seven books appeared under his own name. His first novel, Down and Dirty (1978), was about a gay New York City cop kicked off the police force because of his sexuality. King’s second novel, Night Vision (1979), was set in a mental hospital. Because my brother Robert was gay and had spent most of his life in and out of mental hospitals—and because Robert’s first incarceration in a psych ward occurred when he was 19, the age when King essentially disappeared—those books were more than mildly compelling.

The next day, I phoned several Erasmus friends and told them about King. Rich Ratner, who’d played for Erasmus, put me in touch with Billy Galantai, who, like King, was a Romanian Jew who’d gone to Madison, had been first-team All-City, and had been recruited to play at North Carolina. Unlike King, Billy played varsity basketball at UNC for two years.

Billy told me that after dropping out of college, King enlisted in the Army and wound up incarcerated for a year in its maximum-security prison at Fort Leavenworth, though King would never talk about why he’d been imprisoned. After his discharge in 1955, King returned to Brooklyn and lived with his parents and younger brother, Jonathan. King spent almost every day of the next year at Kelly Park, a neighborhood playground where before and after games of three-man ball, he and Billy hung out in the boiler room basement of the park’s maintenance shack.

Billy talked about King with the awe of a wide-eyed kid. For him, King wasn’t just the greatest ever to play for Madison. “Frankie King was, hands down, the greatest player I ever saw, high school, college, or pro,” he said, and he put me in touch with others who said the same thing.

“I’ve played with and against some of the best, college and pro,” Mel Kessler said, “and it may sound crazy, but Frankie King was the single greatest basketball player I ever saw.” Kessler, who graduated from Madison two years after King, was also a first-team All-City selection. He played for Muhlenberg College when it went up against America’s top college teams, and he still holds Muhlenberg’s all-time single-season scoring record (21.7 points a game). “In those days,” he said, remembering King’s time as a legend at Kelly Park, “the backboards were attached directly to a pole—the supports weren’t set back past the out-of-bounds line the way they are now—and during this one game, King drove smack into the pole and knocked himself unconscious, and when he opened his eyes and asked what happened, we told him he’d smashed head first into the pole. Frankie stood up. ‘But there is no pole! ’ he declared, and walked back onto the court and started playing again as if nothing had happened.”

“I was there that day,” Billy Galantai said when I told him about my conversation with Mel. “On the court, Frankie was totally fearless, and off the court he was one of a kind. Sometimes he’d show up at Kelly Park in street clothes, take off his pants, and play in his underwear.” Billy laughed. “Frank was an enigma—the quietest guy I ever knew, and handsome, like a Hollywood star, and with a killer smile. He smoked before and after he played, but it never seemed to affect his game. He had a range of knowledge way beyond most of us, but before and after games, he never said a word or initiated a conversation. Once a game started, though, he went totally schizo, like some Jekyll-and-Hyde character.”

Billy passed along other rumors: that King was a writer of porn; that he’d been married twice, both times to African-American women (one of whom was a dancer); and that he’d gone mad and was locked up permanently in a mental hospital. Many Madison grads I talked with had known King’s brothers, Steve and Jonathan, but didn’t know where they were now. I talked with King’s old friends and read through The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and New York Post columns about his exploits as a high school star (“Madison’s King Only 15—But He’s Monarch on the Court,” read one typical headline). I also began reading King’s books, and though I was impressed by the sheer range of the subject matter, I was surprised to find nothing about Brooklyn or basketball in any of the first half-dozen I read—this was also true, I would soon learn, about his 37 other books.

King produced three separate series of Lydia Adamson mysteries: one, set in Upstate New York, featuring a woman veterinarian; one whose main character, a retired librarian, was head of the Olmsted Irregulars, a group of Central Park bird watchers; and a series of “cat mysteries” that sold more than a million copies and had an acclaimed actress as its protagonist.

In addition to Down and Dirty and Night Vision, King published five other books under his own name: two novels about Sally Tepper, who with her five stray dogs (Bernstein, Heineken, Molson, Budweiser, and Stout) solved grisly murders; Raya, a novel set in Cairo during World War II about a Jewish prostitute recruited by British intelligence; Southpaw, a gory and fantastical horror novel; and The Anonymous Pornographic Genre, a book about which I could find no information.

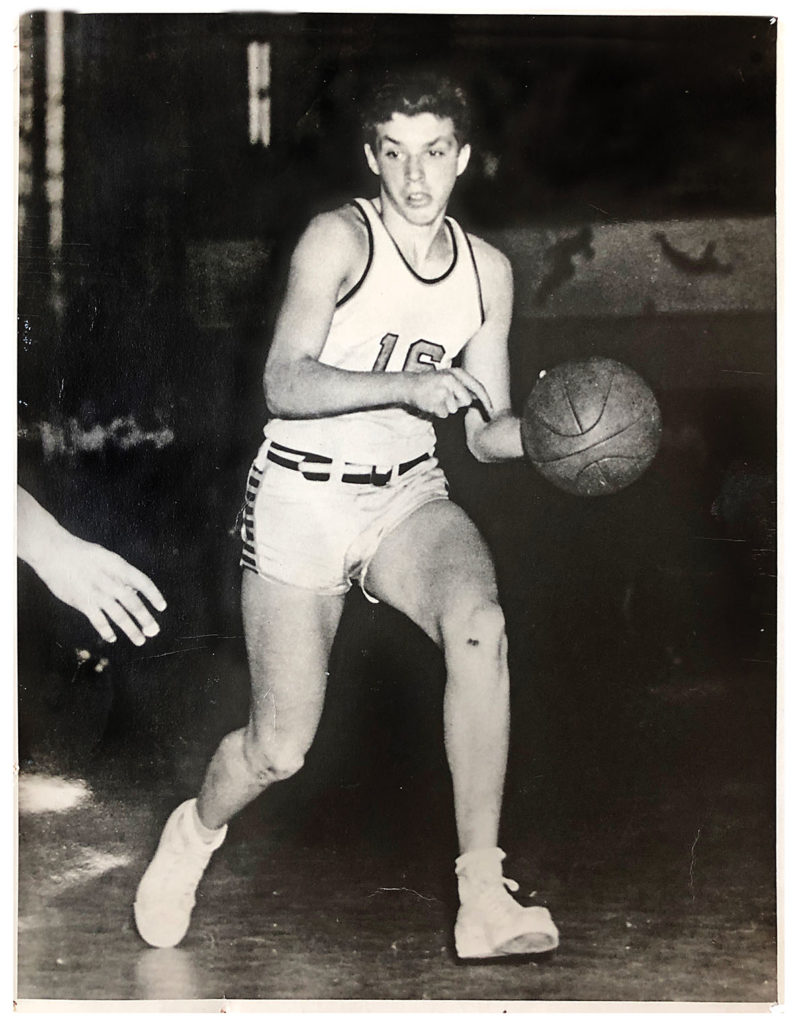

King in 1955 with his mother. His stint in the Army was short-lived, and he ended up incarcerated at Fort Leavenworth. (Courtesy of Stephen King)

On the day I met Ron Carner, my brother Robert left several telephone messages for me. His health, like his ability to control his aggressive impulses, failing rapidly, Robert had been shuttling back and forth between a nursing home in the Bronx and New York City psych wards. Seventy-two years old—the age our father was when he died—Robert was now locked up in the psych ward at Mount Sinai Hospital, where, in addition to a long list of ongoing medical and psychiatric problems (congestive heart failure, drug-induced Parkinsonism, and bipolar disorder among them), he’d been diagnosed with frontal lobe dementia and stage-four renal failure.

Before leaving for the Friars Club, I called Mount Sinai. As soon as Robert came to the phone, he shouted that he’d been calling to wish me a belated happy birthday. “So Happy Birthday, Jacob Mordecai—happy, happy birthday, my big brother!” he said, using the names given to me when I was born, later to be replaced on my birth certificate with Jay Michael. Then he sang “Happy Birthday” to me, after which he began giving me a list of things I should bring when I visited, and naming people I should call so that they could visit him too, some of them friends and relatives who’d passed away years ago.

Robert had spent most of his adult life in and out of mental hospitals, psych wards, and halfway houses, and during these years, I’d been his caretaker and advocate—our parents had bailed out on him early on and moved to Florida. Our father died three years after their move and never saw Robert again; our mother lived for another 30 years, during which she saw Robert twice. Like King, Robert had been exceptionally gifted as a young man—famous in our neighborhood as an actor, a singer, and a dancer. He performed on street corners and in local candy stores and barbershops, and he had leading roles in school and summer camp productions. He was also, in his teenage years, a published poet, winner of a citywide essay contest, a good tennis player, and an excellent chess player. At Erasmus, he and Bobby Fischer were in a chess club together, though Fischer, already National Junior Chess Champion, would say, “With you, Neugeboren, I don’t play.” When Robert would ask why, Fischer would reply, “Because you play crazy.”

Then, five months after Frankie King’s death, I received a message from Columbia Presbyterian Hospital asking me to please call. “We did everything we could,” a doctor said, “but I’m sad to have to tell you that your brother Robert passed away this morning.”

Several weeks later, a Madison grad called to tell me he’d found a phone number, in Philadelphia, for King’s brother Steve. When I reached Steve and explained why I was calling, I mentioned the fact that Robert had passed away recently, and that on the day he died I was in the middle of reading Frank’s novel Night Vision. Steve responded warmly, said he’d be happy to talk with me about Frank, which we did for nearly two hours. “I came to the city whenever I could,” Steve told me, “and what Frank loved most was for the two of us to take long walks together. He’d fill his pockets with coins and dollar bills and give money to every homeless person we passed. I once saw him give a man a $50 bill and not even wait to see the man’s reaction.”

Frank was amazingly productive and loved to have a good time, Steve said, but he was also reclusive, depressed, and troubled at different stages in his life. “He had lots of phobias—about airplanes, subways, doctors, dentists, heights, elevators—and was also extremely claustrophobic,” he told me. “He didn’t take to the modern world much. He never had a cell phone, or even a vacuum cleaner, just an old carpet sweeper, and he wouldn’t use a computer. He wrote his books by hand, printing in block letters, never in script, on yellow legal pads and using an old Smith Corona he typed on with two fingers.”

Frank had had a hard time taking care of himself. “He just couldn’t do it,” Steve said. And so, for most of Frank’s life, Steve had been responsible for him. “He was a chain smoker, an alcoholic, and a gambling addict,” Steve explained. “And from the time he left the Army until he died—for 60 years—he refused to see a doctor or a dentist. By the end of his life, he’d lost all his teeth.” Steve was silent for a few seconds, and when he spoke again, he did so softly. “He and I were very close, and I miss him very much—still—all these months later.” And then: “As different as he was from me, he was my best friend.”

There was so much I wanted to say—so many stories, memories, and feelings stirred up by the news that Steve took care of his brother across a lifetime the way I’d taken care of Robert. And so many sad, strange parallels. Robert, too, had been a chain smoker, an alcoholic, and a gambling addict. Before the end of his life, he had also lost all his teeth. In the moment, however, the only thing I was capable of saying was that Robert was my best friend, too.

Steve and I started talking on a regular basis and getting together. I also began talking and meeting with Steve’s sons, Seth and Rich, and their cousin Andrew, who had spent time with Frank nearly every day during the last seven years of Frank’s life. I met with Frank’s second wife, Charlotte Carter, but I quickly discovered that the questions for which I’d been seeking answers held little interest for any of them. What they wanted to talk about was who King was as a brother, an uncle, and a husband, not his exploits in the gym or as a writer. He had been the single most important individual in each of their lives, and their admiration and love for him had nothing to do with his talents and fame as athlete and author.

After the death of Frank’s first wife, Rima (who had been a dancer with the José Limón Dance Company), the family became concerned that Frank might commit suicide, and so Seth moved in and lived with Frank for three years. Seth told me that when he and Frank were short on cash, Frank would put on the “dorkiest” clothes he had—shorts, black socks, a loose-fitting old T-shirt, shoes or boots—go into Harlem schoolyards looking like a bum, and play guys one-on-one for money. “I think those were probably the last times he ever played basketball,” Seth said, “or even held a basketball in his hands. And I agree with my father that Frank’s gifts as an athlete, and his early fame, seemed to have carried a curse with them—as if by being a star, Uncle Frank felt he was fulfilling other people’s dreams and not his own, and that by dropping out of college, he’d let everybody down.”

Frank worked in his father’s Manhattan furniture store for two years, and after that as a bouncer, a stagehand, and a freelance editor and writer. He wrote a series of books that retold biblical stories, ghostwrote a once-a-week column for a Long Island doctor, and, before he began selling two or three Lydia Adamson mysteries a year, wrote pornographic books.

“He wrote the porn under different names and was paid $500 a book,” Seth said. “He wrote very fast and could turn out a book in a few days. This was after Rima’s death, at a time when he was drinking more than usual and would sometimes wander around the city all night. One night he came home toward morning all wasted and bleeding. When I asked what happened, he said he didn’t really know, but that he’d found himself banging his head against a store window until he realized that what was pouring out of his forehead was blood. ‘That’s it,’ he said. ‘I’ve gone too far.’ And he stopped wandering around the city at night.

“Frank also worked up proposals for at least a dozen other novels I know of. I remember reading one about tubercular Jews on the Lower East Side that took place early in the 20th century, and about underground tunnels they used for smuggling in women and turning them into prostitutes. Frank wrote three chapters and sent them out, but nobody bought it, and when he moved out of the apartment, he got rid of it the way he got rid of everything. He’d sit at his desk and go through boxes of letters, reading them and throwing them away, and then he’d do the same with his manuscripts.

“It was as if, I sometimes think, he spent his entire life preparing to die. We thought his grief over his mother’s death, and then Rima’s, would give him the permission he was looking for to kill himself, but he never did, though he would do things to try to kill himself. Sometimes, after he was done writing for the day, he’d say, ‘Let’s go to Central Park, and I’ll do some wind sprints and see if I can give myself a heart attack.’ So we’d go to Central Park, and he’d do wind sprints until he was bent over trying to catch his breath, but he was too strong to kill himself.

“Frank never slept much, and when he did, he usually slept sitting up in the same chair he sat in when he wrote. He’d go to his desk at about five a.m., a manuscript to the left of his typewriter, and an off-track betting tout sheet to the right. He’d try to finish writing by 10 o’clock, when the off-track betting parlors opened, and on his way to place his bets, he’d have a drink and a chaser.”

Seth’s brother, Rich, a professor of maritime history and literature at the Sea Education Association in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, has published several books about the natural world. What he remembered most was that Frank “completely rejected material goods.” At family gatherings, for example, he’d take out dollar bills and rip them to shreds, or he’d buy a pack of cigarettes, light one, and throw away the pack.

Frank wanted Rich to collaborate with him on a novel—“a naval book,” Rich said, “and maybe the first in a series of books like the Patrick O’Brian books, but set in the time of the American Revolution. Since I taught maritime history, I’d fill in the facts about maritime history, nature, and the sea, and he’d plot the story. ‘I’m great at plotting,’ he told me. He sent me 40 pages, and the book opened with a young guy on a ship on the eve of war.” Frank also asked his brothers, his other two nephews, and Charlotte to collaborate with him in the same way—they’d supply the expertise, he’d supply the plots. None of these books, however, was ever completed.

Frank’s younger brother, Jonathan, a professor of molecular biology at MIT who had polio when he was three years old (yet played football for Madison), said that he’d prefer to put his thoughts down in a memo, and that he wanted, in particular, to remember the period after Frank was discharged from the Army and returned home:

In those days, when I was recovering from polio, I was greatly overweight and always made fun of by my schoolmates, who called me “fatso,” and “two ton.” On the rare occasions when our parents went out, they left Frankie as my babysitter, and he was always affectionate. He treated me differently than anyone else, and that’s the basis of the deep affection I developed for him, and it had nothing to do with his … athletic fame or literary talent.

When he came back from military prison, he clearly was somewhat traumatized, and damaged. I was then in high school. For many years he spent most of the day in his little back room, smoking two packs of Camels … and just coming out for meals. My parents had no idea how to respond—neither did I. Periodically he revealed some aspect of prison life. I remember most vividly his description of long stretches in solitary confinement and the desperate need for cigarettes. He developed a deep affection for the Salvation Army, who provided cigarettes, and an aversion for the Red Cross, who he claimed provided no actual assistance. At some point his athleticism was discovered and he ended up playing quarterback for a prison football team. He never described some of the most horrendous treatment I’m sure he was subject to as an 18-year-old baby-faced late teen among a very hardened and rough prison population.

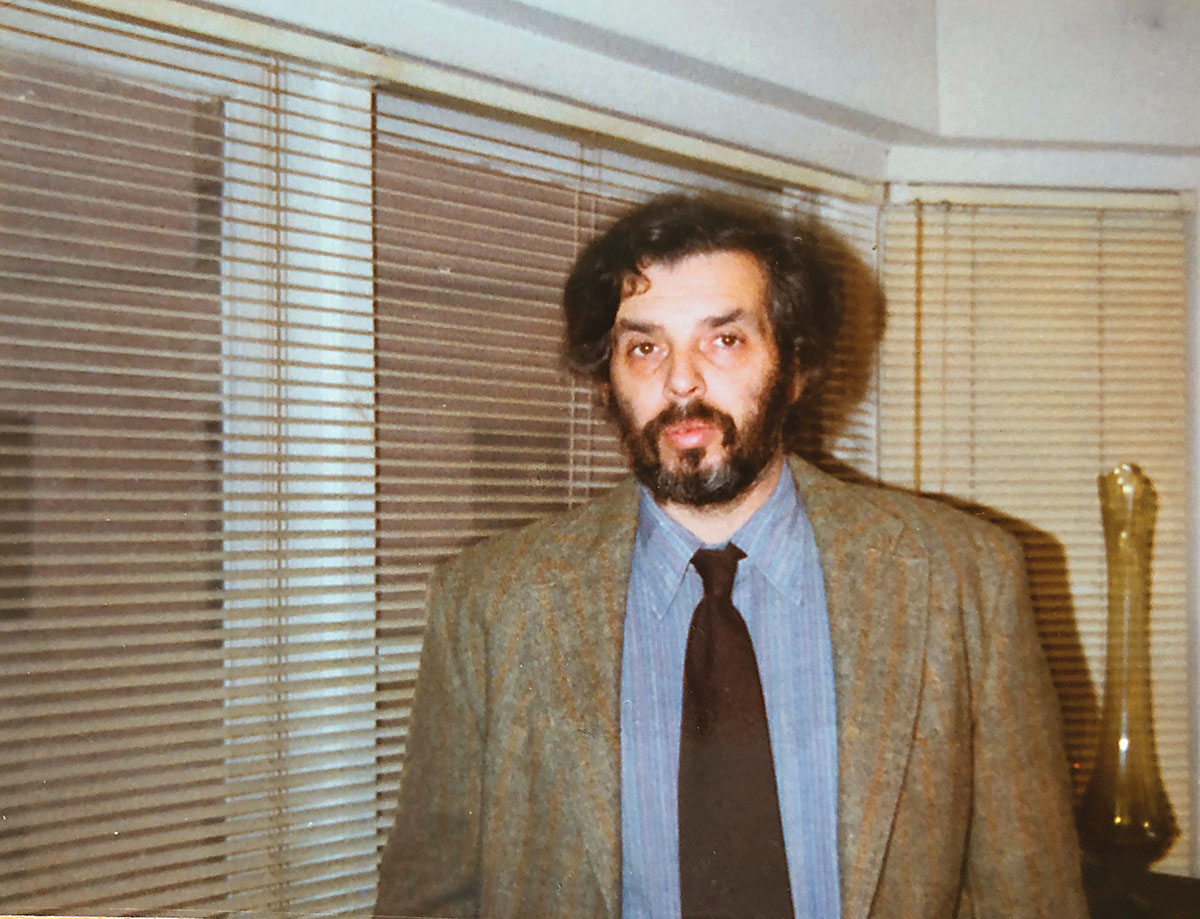

King in the 1970s. He continued to write every day, turning out “dozens of books, proposals, poems, and plays that remained as invisible as he was.” (Courtesy of Stephen King)

“The word Uncle Frank used most often to describe himself was derelict,” Jonathan’s son Andrew said, “and as he got older, he developed more and more phobias. He wouldn’t ride in subways, or go in elevators, and when my mom and dad came to visit him—this was before he and Charlotte were living together—his apartment contained nothing but a chair, a table, a typewriter, and an empty fridge, and he wouldn’t go out of the apartment, so they just ordered in.

“I brought lots of my friends to meet Frank—Blacks, Hispanics, gays, lesbians, Haitians, druggies—and they all fell in love with him.” Frank would let Andrew’s friends go on for a while, after which he’d quietly start what Andrew called “the interrogation.” Frank might begin “lightly” but would soon “fire off question after question—I never met anybody who knew more about Caribbean history, for example, or the history of slavery in America, than Frank—and just as my friends didn’t realize who they were dealing with because of his appearance, maybe it was the same when he played ball, because he probably surprised the other team by being a wizard the way a player like Steph Curry is these days. And he didn’t think anything he’d done in life mattered, including all his books. In fact, he told me several times not to read them—that they were just silly stuff he turned out to earn a buck.”

Charlotte, an award-winning, African-American author of crime novels, was married to Frank for 16 years and, like Frank’s brothers and nephews, was forthcoming during the dozens of times we met. She told me that she and Frank “were both barflies” and that they had been together for several years, and had even watched basketball games together, before she discovered he’d ever played the game, much less been a star. “What you had to understand was that Frank was an actor,” she said. This is why, she believed, different people had different impressions of him. (Frank, I’d learn, had been a member of the Dramatic Workshop, where Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler had taught and where Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, Elaine Stritch, and Tony Curtis had studied.)

“And Frank was consumed with self-loathing,” Charlotte said. Starting with his good looks—which he let go by becoming overweight, letting his teeth rot and fall out, and dressing like a bum—he was determined to spend his life “erasing” himself. “When he moved from one apartment to another, he never took anything with him,” she said. “He destroyed everything he could about himself, including his awards and medals, and dozens of unpublished novels, plays, poems, and book and movie proposals.”

I remembered what Seth had told me: that in the years he and Frank lived together he never once saw Frank look in a mirror, not even to comb his hair, which he did quickly with his fingers. Given such behaviors—along with his addictions, phobias, reclusiveness, and obsessive routines—I asked Charlotte if she’d ever considered the possibility that Frank was on the high-functioning end of the autism spectrum.

“Consider it? ” Charlotte laughed. “Of course he was.”

Through the years, when people learned about Robert’s history, they usually asked—invariably it was their first question—what his diagnosis was, and if I replied with a clinical term like schizophrenia or bipolar, they’d nod knowingly and quickly move on to another subject. As the years went by, I began to reply to this question not with a psychiatric term but with questions of my own: If I tell you my brother has this or that diagnosis, what will you know about Robert? What will you know about his condition, about his life, about who he is?

By consigning Robert to a diagnostic category—by in effect dismissing him from the ordinary ranks of human beings—they wouldn’t have the least sense of who-he-was. How would they ever begin to understand or appreciate that Robert was, in his feelings, thoughts, desires, hopes, and frustrations, at least as complicated and complex a human being as any of us, but with this difference—that he lived not only with a painful awareness of how distinctly unpleasant it was to be mad, and to be institutionalized for being mad, but also with a simultaneous awareness of the life he was not living, had not lived, and would never live.

Although most of us were not, in our early years, as exceptionally gifted as Frank and Robert, weren’t their lives, nevertheless, mirrors to all lives in which early dreams were partially realized, unrealized, destroyed, abandoned, or lost? Didn’t the stories of their lives make us wonder about the lives any of us might have lived? How not wonder about what was writ large in Frank’s life, as in the sad trajectory of my brother’s life, and of how and why it had diverged so radically from the lives of his brothers, and a life he might have led?

I could still see my brother, at four or five years old, tap-dancing on a street corner, then getting down on one knee and, to the delight of a crowd that surrounded him, doing an imitation of Al Jolson belting out “My Mammy.” And I could see him, when he was 15 or 16, dancing across a stage and flying into the air in a grand jeté, his legs spread wide in an airborne split, and then—what brought the house down—a sudden look of feigned horror as he reached down and, in midflight, grabbed at his balls.

And I could see Frankie King, playing for Madison in the Erasmus gym, stopping at the top of the key, bumping his man, then taking a half-step back to give him the space he needed to go up for a left-handed jump shot that swished cleanly through the basket. And later, the gym thundering with foot stomping, King bringing the ball up court, faking right, then moving to his left as if to launch another jump shot but instead doing a crossover dribble to the right, breaking toward the basket, ricocheting off Erasmus players as if in a life-size pinball machine, and from his fingertips—and oh so softly—laying in a shot that silenced the crowd.

In the 23 cat mysteries King wrote, all told in the first-person voice of Alice Nestleton, an actress who, when out of work, supports herself by cat-sitting, there is only one play, Sophocles’s Philoctetes, that receives more than a perfunctory description. Tricia Lamb, the woman who intends to produce and direct the play, tries to persuade Alice to take the part of Odysseus in a production in which all roles, except for the lead, will be played by women:

“The play is not what it seems,” [Tricia] said. “It seems to be about a Greek archer on his way to Troy. He is bitten by a snake, and the wound becomes infected and painful. The stench from the wound and the man’s cries are too much for his comrades to bear … so they abandon him on a desert island. He survives there but his wound will not heal.”

A page later, Trish explains to Alice what interests her about the play:

“Scholars say the play is about the conflict between the individual and the state … or how one must sacrifice one’s own feelings—either likes or dislikes—for the good of the many … in this case the need for the Greeks to conquer Troy.”

“And what do you think?”

“I think that’s nonsense. I think the play is about the wound.”

“I don’t understand.”

“It’s about a wound that will not heal … a wound that becomes increasingly loathsome. It’s about existence.”

In his essay “Philoctetes: The Wound and the Bow,” Edmund Wilson writes that “Philoctetes, like the outlawed Oedipus, is impoverished, humbled, abandoned by his people, exacerbated by hardship and chagrin. He is accursed.” Despite his physical sufferings, Philoctetes, with his bow and his suppurating wound, survives for 10 years in a cave where he “has endured in the teeth of all the cold and the darkness”; he remains a hero “of mysterious virtue whom [his] fellows are forced to respect.” Philoctetes, Wilson writes, dramatizes a “general and fundamental idea: the conception of superior strength as inseparable from disability,” and that “genius and disease, like strength and mutilation, may be bound up together.”

In Sophocles’s rendering of the myth, Odysseus believes he can somehow get Philoctetes’s magic bow “without having Philoctetes on his hands,” as Wilson writes, but “it is in the nature of things—of this world where the divine and the human fuse—that they cannot have the irresistible weapon without its loathsome owner.” For how, Wilson asks, “is the gulf to be got over between the ineffective plight of the bowman and his proper use of his bow, between his ignominy and his destined glory?”

When, years ago, I first read Wilson’s essay, I thought of Robert and of the ways his life paralleled that of Philoctetes, for Robert, too, had an incurable wound (his madness), was abandoned because of the wound (his madness made him repellent to virtually all those who knew him), and yet “endured in the teeth of all the cold and the darkness.”

Frank (right) at 73, with his brothers, Jonathan (left) and Steve (center), in a photo taken in 2009 (Courtesy of Stephen King)

Robert had been a man of incomparable resiliency, and one measure of his resiliency was that he had somehow lived, and with brain, spirit, and sense of humor largely intact, to the same age—72 and a half years—that our father had lived. And he had done so despite being in and out of mental hospitals for five decades, despite being frequently put in isolation for weeks at a time (in a bare, small room containing only a sheetless mattress), despite being beaten up by hospital staff, despite having an abundance of medications poured into him, despite a multitude of medical problems (many brought on by medications and abuse), and despite having been abandoned by parents, relatives, friends, and mental health professionals.

What Wilson writes about Philoctetes and Sophocles’s other tragic heroes and heroines could be said of Robert—that “those who do not get through life so easily are presented … with a very firm grasp on the springs of their abnormal conduct,” and that “these insane or obsessed people … all display a perverse kind of nobility.”

In Frankie King, too, genius and disease—the superior strength and disability, the ignominy and the destined glory—seem to have been inseparable. And, as King’s family believed, his prowess with a basketball, like Philoctetes’s gift with his bow, was a curse that brought about his death as a basketball player, and was central to his self-willed isolation—the cave of his adult years where he cut himself off from those who had believed in the exceptional talents he himself did not value.

For those who never knew about the six decades in which King was hostage to the pain and afflictions that, along with his extraordinary literary productivity, followed on his early brilliance, but knew him only when, for a brief time, he was hailed as one of New York City’s five best high school basketball players, King is trapped forever in the amber of memory: a boy wonder with limitless potential.

In the 60 years after his time in Fort Leavenworth, including 35 years in which he published no books, he continued to write every day—dozens of books, proposals, poems, and plays that remained as invisible as he was. And after not seeing a doctor or dentist during those 60 years, a time in which he remained remarkably strong and healthy (“I have no skills,” he said to Charlotte the day before he died, “but I’m still strong as a bull”), he was done in by an infection in his lower stomach that he refused to have treated—an infection that became a gangrenous and incurable suppurating wound.