When ‘All-Inclusive’ Is Anything But

What’s to become of a modest, beloved vacation retreat?

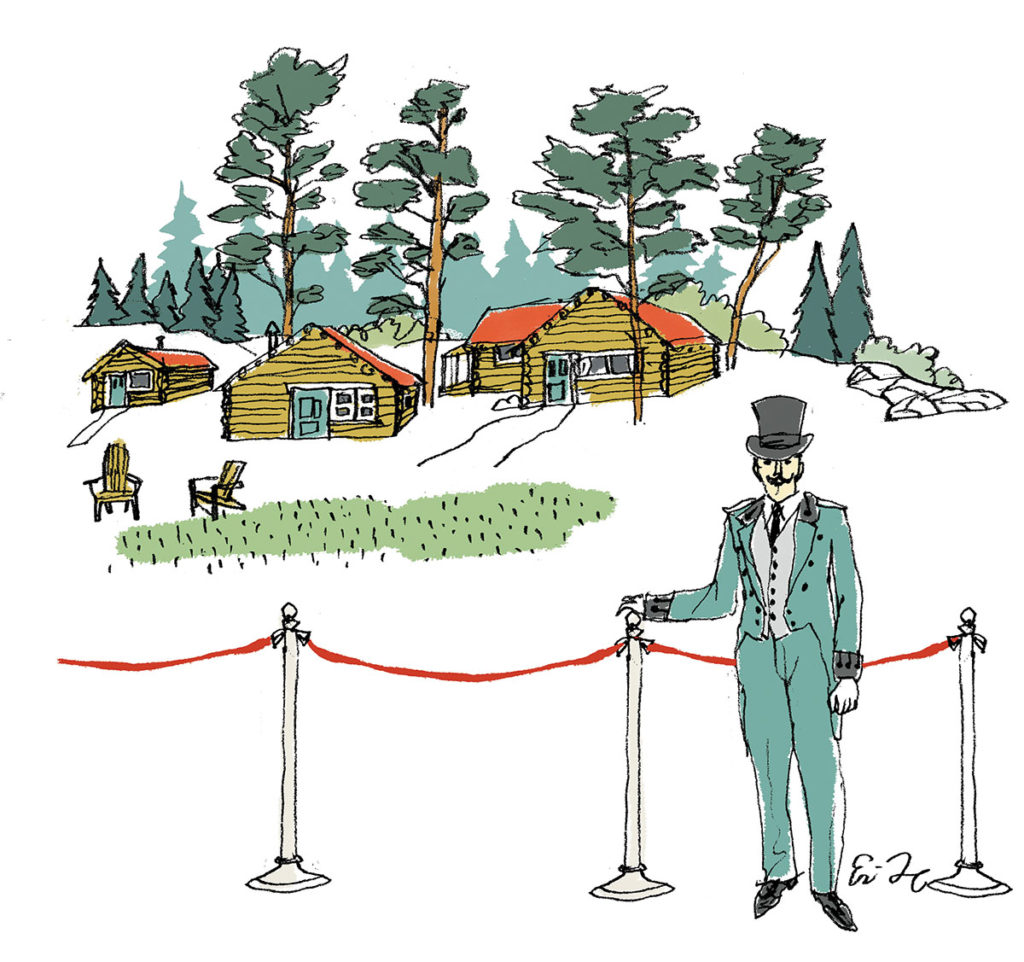

Each summer for the past five years, I’ve been going with family and friends to a modest vacation spot, a short boat ride away from my home in Homer, Alaska. One of the fulcrums of our summer, it’s a bring-your-own-sleeping-bag kind of place, and we stay in simple, plywood-floor cabins, sharing a common bathhouse with hot showers that cost a few dollars extra. We throw together enormous communal meals in a kitchen cabin at the top of the beach, taking turns cooking fish tacos, burgers and dogs, or big spaghetti dinners on an outdoor deck, and then doing dishes in a sink filled with cold creek water.

We pack wetsuits, paddleboards, kayaks, and fishing rods, and we bring our dogs. As we’re hauling hundreds of pounds of gear and food up and down the harbor ramps, we joke that all good Alaskan adventures begin with a schlep. The kids love having the run of the place, launching themselves off a long dock into the cold water of Kachemak Bay, where they wrestle each other off paddleboards and coax the dogs to swim out to meet them. The place is folded pretty well into the area’s wild lands and waters. We’ve seen black bears there. Sea otters frequently swim nearby. And one summer, during a short afternoon ride, with my husband at the helm of our skiff and half a dozen kids aboard, an orca swam right beneath the boat. In the evenings, we have bonfires on the beach as the summer sun hangs late into the sky.

We’ve long known that this beloved vacation spot was for sale. That never stopped us from enjoying it. In December, however, the place finally sold. When I called the new owner to make a reservation for this summer, he told me big changes were coming. Each cabin would now have its own bathroom, but most important, the place was going to become an all-inclusive lodge. No more cooking your own meals. No more making your own fun. Oh, and the new rate would be $1,000 per person, when before we paid $125 for the whole family.

The phone call with the new owner left me simmering for a week. He is from Arizona. He’s been to Homer three times. What right does he have to take away our summer fun? Aren’t there enough opportunities here for the ultrarich? During the 20-some years I’ve lived in this small Alaska town, enormous changes have taken place. New subdivisions have risen on cleared land where no house ever stood. A new hotel has shot up at the edge of the tidal slough in the center of town. Another fancy lodge is being built on a wild, rocky headland across the bay. I’m being priced out of summertime fun. Here and, indeed, all across the United States, people are being priced out of their homes and their livelihoods.

Much of my frustration comes from feeling as though I should have a say in the fate of this place where my children were born and go to school, where I pay taxes, where I donate to good organizations, where I volunteer. Shouldn’t I?

I should have a say, I think, because we loved those summer weekends so fervently. We were grateful for those days, for the happy shrieking of our children as they played, for the clear frigid water we dunked in, for the meals we cooked and shared, and for those wooden bunks—waterproof mattress pads provided—we collapsed into at the end of the day.

I should have a say in what becomes of this place because I love it so hard, because my family, friends, and I have become intimate with it. We know where the wild blueberries are, where to look for chitin among the rocks when the tide goes out, where the wild irises grow in the bog along the trail behind the cabins, how to haul driftwood on a paddleboard from a nearby beach for an evening bonfire.

But that’s not how it goes. The market too often determines the fate of our neighborhoods and towns, our beloved street corners and quiet copses. And though money has nothing to do with the values that we hold, decisions that should be centered around love, around our kids and our communities, are left instead to dollars and cents.

In the end, it doesn’t matter about volunteering, or about blueberries and wild irises, or that we know to watch for the kingfisher that flies laps between the spruce trees at the edge of the beach in front of the cabins. I used to think of loss as a kind of emptying. Now I think of loss as an accumulation, a collection of what we once had that is now too far away.