When Philip Larkin says in his poem Annus Mirabilis, “Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three,” surely he got the year wrong. He must have meant 1968. That was the year that French students, propelled by official prohibitions on visiting the sleeping quarters of the opposite sex, rioted on the cobblestoned Left Bank streets of Paris. Soon joined by workers in the biggest general strike in French history, the uprising led to protests against repression of all kinds. Such disobedience and revolt, according to New Left theorists like Herbert Marcuse, represented the vital, life-affirming force of Eros.

In America, 1968 was the year when The Pill became ubiquitous—if not in actual use, then at least in conversation, since contraception of any kind for unmarried women technically remained illegal in half of the states. That was also the year when Paul Ehrlich’s Population Bomb became a best seller, helping legitimize sexual emancipation’s new moral imperative: The planet has too many people, so don’t have babies. Never before had sexual activity been so divorced from procreation, as negative connotations of premarital sex and promiscuity gave way to the hippies’ chant of “Free Love!”

That year was when Anne Koedt, a member of the group New York Radical Women, dared to publish what would become one of second-wave feminism’s most influential works, “The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm.” Until Koedt’s essay, the predominant thinking among medical and psychological professionals—virtually all males—discounted the primacy of the clitoris in female orgasms. Women were now “liberated” from the patriarchal view that true sexual fulfilment was possible only through penetrative, heterosexual intercourse. To protest other sexual stereotypes, feminists staged a demonstration at the Miss America pageant that year. If young men could burn their draft cards, women could burn their bras.

But as women asserted control over their bodies, they were objectified to a commercial extent never before seen. “Sex sells!” became the mantra from Madison Avenue to Main Street. Hugh Hefner’s Playboy empire was at its zenith, and the era that would become known as the “Golden Age of Porn” was about to commence. In 1968, puritanical America whispered a Molly Bloom-like “yes” to the Sexual Revolution.

And 1968 was the year that, as a U.S. Army draftee stationed stateside waiting for orders, I happened to meet the college girl who, a couple of years later, would become my wife. All the countless obstacles (from all-girl-college rules to Army regulations) only enhanced our ardor, and the likelihood that I would soon be shipped to Vietnam, possibly to die there, acted as both an aphrodisiac and a hallucinogenic. One especially memorable weekend transported us, in my ratty, beer-can-littered VW Beetle, to a Poconos resort known for its “honeymoon cabins.” Checking in and pretending to be “just married” felt delightfully subversive.

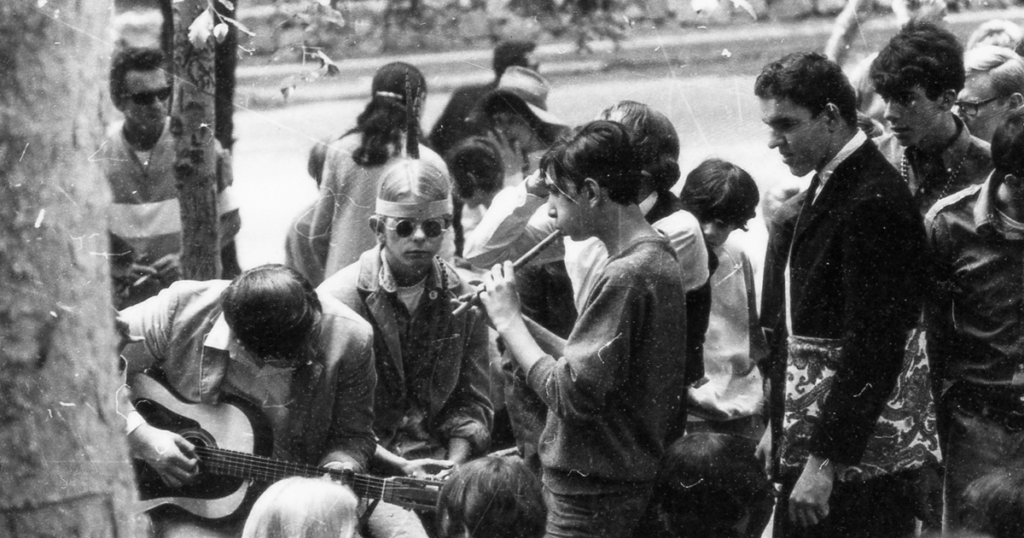

Also delightfully subversive was the rock musical Hair, which opened on Broadway that year. Infused with erotic energy and subtitled “The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical,” it would run for 1,750 performances. With long hair as a synecdoche for hippie counterculture, the interracial cast played up every possible anti-establishment trope: nudity, profanity, sexuality, drug use, antiwar rhetoric, and irreverent treatment of the American flag. Many of the musical’s songs became pop hits, including “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In” as well as its signature song, “Hair,” an anthem, celebrating long hair as a kind of supranational flag. The song’s “long beautiful hair”—whether “gleaming,” “streaming,” or “bangled,” “tangled,” or “spangled”—symbolized rebellion, rejected restrictive gender roles, and united protestors from France to California.

While Hair idealistically portrayed sexuality as a way to bring everyone together in “harmony and understanding,” a fictional character named Myra Breckinridge in Gore Vidal’s eponymous novel, published that year, made sex the ultimate weapon. For traditionalists in today’s America upset about transgender access to bathrooms, Vidal’s transsexual narrator confirms their very worst fears, as Myra’s self-proclaimed mission is no less than “the destruction of the last vestigial traces of traditional manhood in the race in order to realign the sexes, thus reducing population while increasing human happiness and preparing [humanity] for its next stage.”

If population statistics are the measure, however, Myra certainly failed. The number of people on the planet in 1968 was 3.5 billion; it has now more than doubled. Failed, too, within just two short years, would be my own (first) marriage.

It didn’t turn out the way it was envisioned. What, from 50 years ago, has? Our youthful, aspirational assumptions for America?