Whiskey Foxtrot One-One

My father was training to fight a war, but his real battle was with himself

My father, Ron Zobenica, had been a fighter pilot in the Marines, and his stories were filled with place names that, through repetition and association, took on a kind of lyrical air: Quantico, Pensacola, Meridian, Beeville, Cherry Point, Camp Lejeune, Saufley Field, and so on. Ron and my mom, Sandy, lived in Meridian, Mississippi, from May to November of 1964. Sandy was pregnant when they arrived, and my older sister, Haidee, was born in Meridian in September of that year. Ron was in basic jet training at McCain Field (subsequently renamed Naval Air Station Meridian) north of town.

It was the Freedom Summer, when civil rights workers were pushing to register as many black voters as possible in Mississippi in the lead-up to the fall election. The registration drive included young volunteers from the North, who came south to take part in the campaign. Speaking in a northern accent in Mississippi that summer could earn one anything from suspicion to hostility from the local white establishment, who resented the intrusions and the political agitations. Although my parents, both from the Upper Midwest, lived in off-base housing, Sandy did most of her shopping and errand running at the base commissary and PX rather than venture into downtown Meridian. Being plump with child, she did not attract suspicion as a Freedom Summer volunteer, but she was obviously a young northerner at a time when locals knew that such people looked down on Mississippi folkways.

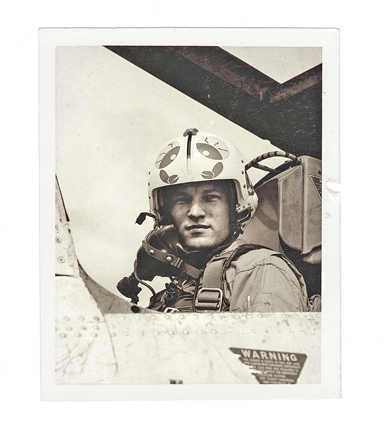

Marine Second Lieutenant Ron Zobenica during basic jet training at McCain Field (now Naval Air Station Meridian), Mississippi, 1964. (Courtesy of the author)

The summer air crackled with a mix of pride, guilt, and resentment, to say nothing of potential violence, all of which made even the simplest interactions fraught, no matter the amount of southern courtesy brought to bear. (Tensions ran higher still when, late that June, the civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi, and personnel from McCain Field, including my father, were pulled off duty to man a sector-by-sector search for their bodies in the surrounding swamps.) Sandy didn’t want to upset people, since doing so upset her as well, so she kept to her own: the itinerant military community, made up of people from everywhere who, owing to the nature of military training schedules, didn’t stay anywhere very long.

They had their own folkways, those of a flying circus. Six months of officer’s basic school in Quantico, Virginia, was followed by five months of primary flight training in Pensacola, Florida, followed by six or seven months of basic jet training in Meridian, followed by four months of aerial-gunnery training and carrier qualifications back in Pensacola, followed by five or six months of advanced jet training in Beeville, Texas, and so on.

The trainees and their wives often became fast friends with one another and would, according to training schedules, move in near sync from town to town, state to state, station to station. Upon arrival, they might overlap briefly with the trainees and wives just ahead of them in the schedule—people they had come to know and befriend as well, who were helpful in getting the new group situated. Shortly before their own departures, Ron and Sandy’s group would play a similar role with the group just behind them.

Thus did the rootless military social scene progress.

For all his training, however, Ron never made it to Vietnam.

After finishing up exercises in air combat maneuvering (dogfighting) in Beeville, flying the F-11 Tiger, Ron earned his Naval Aviator wings and was sent to Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, near Havelock, North Carolina, in July of 1965. There he began logging hours in the F-4B Phantom II, in advance of being sent overseas.

On February 24, 1966, with orders already in for a May deployment to Da Nang, Ron was sent aloft in bad weather to undertake a series of ground-controlled approaches at Myrtle Beach Air Force Base, in South Carolina, all for the purpose of gaining ever more proficiency in night navigation and instrument flying. Preflight instructions had included a reminder that the approach-light system at Cherry Point would be turned off that day. The system had been out of use for months, pending tree clearing between some newly installed banks of lights—and therefore the only lights visible on the return approach would be runway lights.

As night fell, the cloud ceiling did as well, down to 100 feet, with fog and drizzle. The squadron duty officer, a good friend who was also on Ron’s “confidential sheet” as a person designated to inform Sandy in the event of an emergency, called Sandy around six o’clock to say that Ron was inbound and would make one attempt to land at Cherry Point, and if that proved impossible, he’d be dispatched back to Myrtle Beach for the night. Either way, the duty officer would call again shortly.

Sandy had been frosting a cake, and like most Marine Corps wives would, she took the news casually, as if she’d been told nothing more worrisome than that a meeting had gone long. She put Haidee to bed and returned with untroubled attention to the cake, enjoying the personal time afforded by a slumbering daughter and a husband running late. Only after rinsing off her spatula did she realize that this idyll had ballooned to ominous proportion, and that the call—any call—was overdue.

She knew bad news was coming. The only question was how soon and how bad. Flipping on the porch light, she sat and waited for the doorbell to ring. When it finally did, announcing the arrival of the duty officer and his wife, Sandy was relieved not to find a chaplain standing on her doorstep.

Ron had gone down short of the runway, in the kind of snafu that routinely claims a small but steady percentage of military lives. Without notification, someone—probably with the best of intentions—had turned on the approach lights at Cherry Point, resulting in a simple but disastrous change to the visual cues that Ron expected based on preflight notifications.

Flying the radar beam on a ground-controlled instrument approach in the dark fog, Ron had spotted a narrow row of parallel lights that seemed to indicate he was coming in high of the runway. He steepened his descent accordingly, began hitting trees, and then threw on the afterburners in an attempt to regain altitude, but instead sliced his way through roughly 750 feet of forest, coming to an eventual stop in a creek bed.

The control tower, with eerie calm, kept trying to reach him. “Whiskey Foxtrot One-One, you’ve dropped below the glide path. Respond. Over … Whiskey Foxtrot One-One, you’ve dropped below the glide path. Respond. Over … Whiskey Foxtrot One-One, you’ve dropped below the glide path. Respond. Over …”

Briefly knocked unconscious by a tree that had cracked his helmet, Ron woke to find himself strapped to the forwardmost part of the aircraft, the entire nose structure having been ripped away. There was a tree lying in his lap and another lying at an angle such that he could rest his head against it.

Lashing branches or flying debris had inadvertently switched on the survival light that was attached to his torso harness, and in the illumination, he spotted his right boot with bone sticking through the shin area of his flight suit. He moved his thigh from side to side to ascertain whether his lower leg was still attached. It was. However, the lower portion of his left leg seemed to be missing, and jiggling that thigh produced no apparent resistance. While fashioning a tourniquet out of some rubber debris to put around the presumable stump, he heard an explosion and some swearing behind him. His radar intercept officer (RIO), in the back seat, had blown his canopy in an attempt to dislodge a tree, but the tree had fallen back down, nearly hitting him.

Fading in and out of consciousness, Ron next heard a helicopter overhead and felt the RIO yanking on his shoulder holster. Realizing what was happening, Ron pulled the revolver out and fired several tracers across a searchlight beam playing through the fog. The searchlight then went out. As Ron began losing consciousness again, he handed the revolver to the RIO, who sent nearly 20 more rounds skyward, emptying Ron’s bandolier and burning out the barrel of the revolver in the process.

The helicopter pilot later complained of nearly being shot down, but he had managed to fix a location and determine the existence of survivors. When the crash crew arrived and began trying to extricate Ron from the tangle, he learned that his lower left leg hadn’t been severed after all, but had been dragged under the plane and pulverized (he sustained 16 fractures below the knee). He also realized that one of the many trees he’d collided with had initiated the ejection-seat firing sequence by snagging on and yanking down metal loops, situated above the pilot’s head, that are used to draw out a protective air-blast curtain. If the crash crew weren’t careful, the final ejection would be triggered, blowing the now-armed seat and maiming anyone in or near it. He screamed for them to stop until the RIO could secure a pin that would prevent the explosive cartridge from firing.

Medevaced through the woods and stabilized at Cherry Point, he was then transferred to Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, where he insisted that the orthopedists not amputate that night. As he put it later, “I didn’t want to wake up with my leg in a dumpster.” In a poignant display of youthfulness (he was only 25 at the time), he also refused to let the doctors take scissors to the high school letter sweater he was wearing under his bloody flight suit, making them instead gently peel it off him.

Sixteen months later—after enduring everything from bone grafts and plaster casts to a partial ankle fusion and a crude fracture-reducing device called a Stader splint—Ron was able to walk, awkwardly, on both legs, without having lost so much as a toe.

In the early phase of this long medical ordeal, I was somehow conceived. As a teen, I asked my mom if it had happened in a military-hospital bed, à la The World According to Garp. She simply blushed and said that it had involved no such thing. Yet when I was born, at Cherry Point, my dad was again in the hospital at Camp Lejeune, recovering from one of his many surgeries.

Years later, knowing that Ron had a reel-to-reel recording and a transcript of his fateful approach, my young friends and I would encourage him to put on the tape and reenact the crash for us, never guessing that doing so might have been unpleasant for him. Reluctantly, he sometimes obliged. To us, the only thing cooler than flying a mean-looking jet was smashing one up in a bloody crash and living to tell about it. We couldn’t imagine that someone wouldn’t want to brag about that at every opportunity, regaling youngsters as if it were a tale of pure glory.

With the help of somebody who cooked the flight log, Ron undertook a few last hops as a Naval Aviator—copiloting a C-47 cargo plane on parts-and-supply runs. The rule bending was required because he was not assigned to flight duty anymore. Medically speaking, he would not have been deemed airworthy in any event (he was still on crutches). But for personal reasons, he needed his last takeoff in uniform to end in a successful landing. The last few did, and he walked away. In 1968, he was medically retired by the Marine Corps.

An aviator’s prayer Ron once shared with me went, “Please, God, don’t let me fuck up, and if I do, don’t let me live.”

The day before Ron’s crash, one of the members of his four-man training division died at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma when his F-8 Crusader caught fire after takeoff. The pilot, “Dutch” Holland, was unable to eject, because he’d left his ejection-seat pins in instead of removing them as he should have done during the routine preflight check and preparation of the plane.

When Ron and Dutch had been going through advanced jet training together in Beeville, Dutch would get impatient with Ron for being too methodical with his own preflight checks, which forced Dutch to wait on the flight line under the hot Texas sun. Ron once angrily replied that he sure hoped Dutch wouldn’t one day rush through preflight, find himself in a jam, and then discover that he’d done something stupid like leave his seat pins in.

While lying in intensive care after his own accident, Ron heard of Dutch’s death—the how and why of it. The news convulsed and nauseated him. In roughly 30 hours’ time, and before ever entering a combat zone, half his training group had been killed or grievously wounded.

A military investigation validated Ron’s unwitting descent into the trees, his dropping below the control tower’s prescribed glide path, since he’d done so in reaction to visual cues, never having been informed of the change in approach light status, and since even in ground-controlled approaches, it’s standard practice for pilots to take command of the approach upon making visual contact with the runway.

Such validation, however, was cold comfort.

As Tom Wolfe points out in The Right Stuff, according to the unspoken terms of the egomaniacal fighter-pilot fraternity, he who crashes or gets shot down does so only through some exceptional personal lapse that leaves the rule of fighter-pilot infallibility intact. True, a whole host of problems and obstacles may, through no fault of one’s own, beset one at any time, but it’s axiomatic that the best of the best will find a way out of such jams. Ron had done so himself numerous times.

It’s not that those who fail to work themselves out of a predicament are considered unworthy. Indeed, they’re saluted for having had the moxie to meet, without fear of consequence, their own personal limit. But the delimiting itself, whether real or imagined, can hurt more than a shattered limb.

Ron remained in explicitly high esteem among his confreres, and in fact became something of a legend for having walked away, in an eventual sense, from a crash of that magnitude. Still, finding himself demoted to groundling father while his friends flew off to war was not easy, and the bitter voice of ego—it later occurred to me—never stopped whispering insinuations into Ron’s ear, insinuations that could darken exchanges even (perhaps especially) with his closest pilot friends.

One of those friends, a squadron mate named Harry Lake, became Ron’s brother-in-law when Harry married Sandy’s sister, Sue. Harry flew combat missions in Vietnam and served as a forward air controller at Khe Sanh, and afterward he took up flying commercially for Delta Air Lines. Starting soon after the war, Ron and Sandy began taking their family down to suburban Atlanta each year for extended visits with Sue and Harry and their young family. (At the time, we were living in the Upper Midwest, first Iowa and then northern Minnesota.)

Harry was the roguish uncle to my sister, Haidee, and me—loud, funny, generous. He was apt to poke us under the dinner table with his fork and then encourage us to call each other names, all while teasing Sue and flirting with Sandy, whose delight was evident. Harry had the easygoing air of a guy who’d discovered, circumstantially, that he had some pretty righteous stuff. The continuity and completeness of his military experiences—a three-act drama of prewar, war, and postwar—allowed Harry to live cheerfully in the civilian present, following a segue that was about as smooth as a line officer could reasonably expect.

Ron, by contrast, in those early days after the war, had a regular tendency to bring his conversations with Harry around to the night Ron’s military career had come to its premature end. His anguish would mount—and seem compounded, even, by Harry’s affirmations, which, though sought, probably had demoralizing if unintended hints of pity about them, not least because those affirmations had been prompted by Ron himself. Being unresolvable, these dialogues could only exhaust themselves for the night, to be resumed unhappily some evening hence.

Having been habituated to Ron’s foul turns in temper, I saw nothing extraordinary in these displays, other than the fact that he needed such affirmations. I liked hearing them in any event, since they buttressed further my complete, boyish faith in my father.

As the 1970s wore into the early 1980s, the dark moods, at least relative to the crash, subsided to a degree, with nostalgia overtaking resentment. By then, our family trips to the South had become sentimental journeys, and much to the dismay of a sullen, teenage Haidee, the family would visit not just Sue and Harry and their kids but also an expanding array of old military haunts and acquaintances.

A young war buff, I enjoyed seeing any military installation, especially one that had been home to my family. I’d note the wistful glow that overcame my parents as we all cruised by this or that address: “There’s the BOQ where Harry lived,” Ron might remark, “where he stumbled home drunk after crashing his motorcycle and then wondered in the morning where he’d dumped it. Christ, I can’t believe we let him go out with your sister.” Ron and Sandy’s past seemed the stuff of ancient legend (though the time gap was roughly 15 years), and I would imagine being old enough to access such bittersweetness.

We’d visit decommissioned airfields and stare out at weed-choked tarmacs once so alive with sputtering trainers, or stop by naval yards and stand in the shadows of giant warships—perhaps an aircraft carrier Ron had launched from and landed on. We’d drive hours to get to a remote southern hamlet from which a buddy from boot camp had hailed, on the chance that he had returned there after leaving the Corps. Once we arrived in town, Ron would stop at a pay phone to consult the white pages, and as likely as not we’d soon find ourselves on the screened-in porch of a friendly if somewhat startled man who would serve up cans of beer and wonder how to entertain two car-sprung kids while he and Ron reminisced about 20-mile marches and the profane felicity of drill instructors.

We’d visit Diz, a squadron mate and mentor of Ron’s who, having already completed a combat tour overseas, had closely attended my father during his long recuperation from the crash. At the time of our visits, Diz lived on a grass airstrip in Vero Beach, Florida, with certain neighbors rumored to be moonlight drug runners. More than once, he took us up in his own plane, popping unannounced barrel rolls and buzzing light buoys at a range meant to make me flinch, which it did.

Compared with life up north, the southern military scene seemed piratical—with its fierce-looking ships, its tropical foliage and sea breezes, its sunburned rogues. Ron’s peg-legged gait as he walked happily with his buddies contributed to the effect, as did the fact that his old squadron had had a one-eyed owl as a mascot. Ron and the owl’s broken bodies conveyed a kind of nonchalance toward injury.

No such military culture existed in Minnesota. Over on the plains of neighboring North Dakota, there were underground silos with missiles coded to fly polar routes into the USSR, and there were B-52 crews dispatched to lurk in Arctic air, but the Strategic Air Command was void of panache.

Ron’s crash was often spoken of, by people other than Ron, as a blessing in disguise—God’s way of keeping him from going off to Indochina and getting killed, or shot down and captured; God’s way of keeping his wife from being widowed, his daughter from being orphaned, and his parents from losing a son.

Except in his most abstract, philosophical moments, Ron himself didn’t see it that way. Mere months from deployment at the time of the crash, he had—of necessity—been keyed up for war. He’d gone through not only two years of technical training but also, more recently, the moral struggles by which he justified (to himself) what he was about to do. Although thou shalt not kill, he’d found fine print in the Ten Commandments to the effect that kill really meant murder, and since war is an affair of state, an extension of politics by other means, killing in that context (including killing noncombatants collaterally) is not a matter of individual culpability, and is therefore not murder, and therefore not a sin.

He had to tell himself that, he later remarked, or he’d have gone out of his mind thinking about possible unintended victims of his airstrikes, which is fair enough. Also fair is that the surviving members of a napalmed family could hardly have been expected to parse the matter so neatly. C’est la guerre.

One of the ironies of Ron’s life, however, is that owing to his blessing in disguise, those heavy contemplations never found release or mitigation, since he never got to experience the actual, universal miseries of war. Instead, those contemplations became a source of permanent tension, part of a cliffhanger end to a chapter in a life that abruptly, unexpectedly moved on to unrelated dramas.

Ron was never happier than when he was with his Marine buddies. Hobbling among them in springtime southern air, he was the image of contentment. But part and parcel of that happiness was a peculiar vulnerability—the sort of vulnerability that informs military historian S. L. A. Marshall’s observation that a brother-in-arms tends to value above all else his “reputation as a man among other men.” Marshall, significantly, was speaking of a man in combat, and of such a man being more afraid to lose face than to lose his life.

Ron’s friends had come home from history’s main stage (if they survived) with whatever attitude suited them from firsthand experience. But Ron, who had been right alongside them until one fateful evening, now existed on the other side of an experiential divide. His reputation was safe, earned without question or qualification from his peers. But it was safe partly for the infuriating (to him) reason that he’d been denied the opportunity to go overseas to test his mettle alongside them, and as a consequence he could not now presume to adopt their tones (solemnity, gruff wit, bitterness, whatever) without possibly seeming to protest too much.

Another irony of Ron’s life is that as he convalesced at Cherry Point, no doubt lamenting that his training had come to naught, letters home to him from his various friends overseas complained—almost without exception—that jet pilots were being given maddeningly few missions and were instead being reassigned to work with the ground forces, as forward air controllers (FACs).

In a letter to Ron and Sandy dated March 9, 1967, Harry Lake, who was then serving as a FAC at Khe Sanh, reeled off the names of fellow fighter pilots who’d already drawn such duty or were expected to do so shortly. In what was perhaps the most (inadvertently) wounding line of correspondence Ron received during the war, Harry cut short his list by saying that it included “many others I don’t think you know.”

Among the fighter pilots Ron did know who drew such duty, one was killed in May of that year by a short mortar round (i.e., friendly fire) and another was shot in the head by a sniper. In this grubby ground war, as Harry noted, no helicopter pilots were being taken for FAC duty.

One of those helicopter pilots was Ron’s brother Pete, whose letters to Ron and Sandy complained not of his being underutilized but of what a “fiasco” the war—as conducted—was. In one letter, dated December 19, 1968, he revealed that his helicopter (a CH-46 Sea Knight) had taken 15 rounds of ground fire on a recent mission. In another, dated January 25, 1969, he mentioned being part of an effort to retrieve a battalion of Marines that had been “chopped up” by widely dispersed booby traps on the Batangan Peninsula. “So far,” Pete wrote, “we’ve medevaced 62—46 WIA’s & 16 KIA’s. It’s a tragic sight—if I see it a hundred more times it will never lose its impact. This G.D. war had better be worth it—I refrain from giving my opinion on it due to my professional obligation.”

Six years later, I found my dad glowering at the television, which was showing American helicopters, one by one, struggling to get aloft from a rooftop as a long, snaking line of people overloaded each aircraft while it perched briefly on a small helipad. That same evening or very soon thereafter, the TV also showed American-made helicopters being pushed over the side of a U.S. aircraft carrier at sea, the sinking choppers taking to the bottom any hope that the goddamn war had been worth it.

My dad made me sit and watch for a while, but my questions about what exactly the TV was showing were met by an uncharacteristic, almost frightening inarticulateness on his part. His inability that evening to put his anger into words was like a sudden aphasia brought on by poisonous grief and a despicable feeling of impotence. The mood, in its way, was more upsetting than the loudest rage, and I left the room as soon as I was allowed to do so.

Ron and Sandy, like many young parents of the time, had an 8mm camera with which they would shoot soundless family movies. Most footage was of the usual sort: children opening Christmas gifts, riding tricycles, stepping into or jumping down from school buses, running through back-yard sprinklers in summertime, and clambering over back-yard snowdrifts in winter.

Quite a few rolls were dedicated to air shows. But the greatest single stretch of family film—more than 10 minutes long, at once the most boring segment and, with time, the most compelling—was of the 1970 veishea parade at Iowa State University. veishea (pronounced VEE-sha) is an acronym derived from the first letters of the various colleges that made up the university at the time the annual spring festival first occurred: Veterinary Medicine, Engineering, Industrial Science, Home Economics, and Agriculture.

Ron had obtained an engineering degree from Iowa State just prior to being commissioned in the Marines, and now, less than 10 years later, semi-crippled and retired from the Corps, he was back at ISU, about to pursue a degree in veterinary medicine with the help of the GI Bill. It wasn’t a homecoming parade, but it was like one for Ron, and bittersweet. Ron always loved a parade—a pass in review of Americana and lighthearted, martial informality. Styles had changed since he’d been gone, but for the most part, the parade was akin to those he had seen in his undergraduate days, featuring majorettes and marching bands, beauty queens on elaborate floats, color guards, Shriners on motorcycles.

Then, after six minutes of such quick-cut, wholesome monotony, a group of scruffy young men abruptly appears, moving across the frame from left to right, dragging a symbolically wounded comrade on a kind of travois. One of the men, in cut-off jeans, holds forth a sign that can’t be read from the angle captured on the film. Immediately thereafter, in another quick cut, a group approaches from the left carrying a large sign that reads:

VEISHEA ’70

“While we play others die”

Vietnam • Laos • Cambodia • Kent State

The shooting at Kent State had happened no more than a week or so prior to that year’s veishea parade, and came during a campus protest of the recent invasion of Cambodia.

Another quick cut brings a marcher holding up a sign that reads, “Mickey Mouse wears a Spiro Agnew watch,” a popular gibe on campuses across the country at the time. In the foreground strolls a young man in sunglasses who is staring at the camera unnaturally as he progresses, as if the parader has become the spectator to some attention-getter along the route. Then, without adjusting his gaze, and no doubt in response to something Ron is shouting, the marcher breaks into an ill-intended smile and flashes a peace sign on the end of a horizontally extended arm—a salute he keeps aimed at Ron while proceeding off the frame, his head swiveling over his shoulder as he goes so that he can savor the effect he’s having on the embittered man with the camera. In the next cut, another marcher holding a sign (unreadable), who had clearly picked up the commotion farther ahead, wastes no time locking eyes with and laying a peace sign on Ron, also holding it for the length of his time on camera.

Ron was 29 years old that spring.

You can’t go home again.

He did, however, return to Minnesota, where he practiced veterinary medicine for nearly 30 years. He’s still there, retired, hobbling along on the same patchwork approximation of legs that emerged from that violent night in North Carolina in 1966. His and Sandy’s marriage, on the other hand, succumbed to injuries long ago.

And yet, in the spirit of recovery, a workable friendship has been restored.