Lately, as I’ve been working on my second book, a meditation on the absurdity of sorting human beings into metaphorical color categories, I’ve been thinking a lot about the concept of passing. In his 1948 autobiography, A Man Called White, the pale-skinned, blond-haired, blue-eyed former NAACP leader, Walter White, observed, “Many Negroes are judged as whites. Every year approximately twelve-thousand white-skinned Negroes disappear—people whose absence cannot be explained by death or emigration.” Or as Henry Louis Gates Jr. has tabulated more recently, “How many ostensibly ‘white’ Americans walking around today would be classified as ‘black’ under the one-drop rule? Judging by the last U.S. Census, 7,872,702. To put that in context, that number is equal to roughly 20 percent, or a fifth, of the total number of people identified as African American in the same census count!”

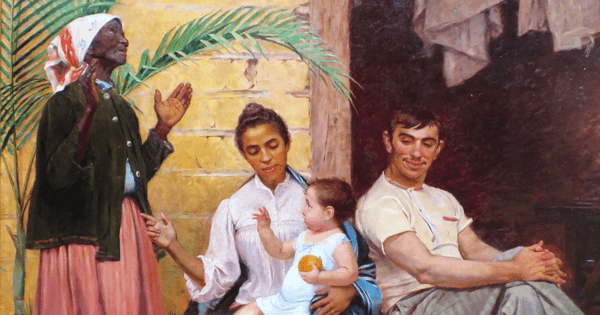

Alongside the article in which that Gates quotation appeared, there was a stunning image of The Redemption of Ham, an 1895 painting by the Brazilian artist Modesto Brocos y Gómez. Its subject is the colonial practice of blanqueamiento (or “whitening”) through the process of marrying someone with lighter skin in order to produce lighter-skinned offspring. In the painting, an elderly, dark-skinned grandmother stands to the left of a young mixed-race mother, white father, and white baby. Her hands raised, the grandmother gives thanks to God that her grandson is white. I had never seen this painting before, and though I still can’t tell if the artist is critiquing or celebrating blanqueamiento, the human-scale illustration of the practice and of the internalized violence of the racism it derives from haunts me.

I wonder how many descendants of those newly minted white babies know from whence they came? How many of us are who we think we are?