A little over five years ago, a pair of huge, exquisitely crafted L-shaped antennas in Louisiana and Washington State picked up the chirping echo of two black holes colliding in space a billion years ago—and a billion light years away. In that echo, astrophysicists found proof of Einstein’s theory of gravitational waves—at a cost of more than $1 billion. If you ask why we needed this information, what was the use of it, you might as well ask—as Ben Franklin once did—“what is the use of a newborn baby?” Like a newborn’s potential, the value of a scientific discovery is limitless. It cannot be calculated, and it needs no justification.

But the humanities do. Once upon a time, no one asked why we needed to study the humanities because their value was considered self-evident, just like the value of scientific discovery. Now these two values have sharply diverged. Given the staggering cost of a four-year college education, which now exceeds $300,000 at institutions like Dartmouth College (where I taught for nearly 40 years), how can we justify the study of subjects such as literature? The Summer 2021 newsletter of the Modern Language Association reports a troubling statistic about American colleges and universities: from 2009 to 2019, the percentage of bachelor’s degrees awarded in modern languages and literature has plunged by 29 percent. “Where Have All the Majors Gone?” asks the article. But here’s a more pragmatic question: what sort of dividends does the study of literature pay, out there in the real world?

Right now, the readiest answer to this question is that it stretches the mind by exposing it to many different perspectives and thus prepares the student for what is widely thought to be the most exciting job of our time: entrepreneurship. In William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, the story of how a rural Mississippi family comes to bury its matriarch is told from 15 points of view. To study such a novel is to be forced to reckon with perspectives that are not just different but radically contradictory, and thus to develop the kind of adaptability that it takes to succeed in business, where the budding entrepreneur must learn how to satisfy customers with various needs and where he or she must also be ever ready to adapt to changing needs and changing times.

But there’s a big problem with this way of justifying the study of literature. If all you want is entrepreneurial adaptability, you can probably gain it much more efficiently by going to business school. You don’t need a novel by Faulkner—or anyone else.

Nevertheless, you could argue that literature exemplifies writing at its best, and thus trains students how to communicate in something other than tweets and text messages. To study literature is not just to see the rules of grammar at work but to discover such things as the symmetry of parallel structure and the concentrated burst of metaphor: two prime instruments of organization. Henry Adams once wrote that “nothing in education is more astonishing than the amount of ignorance it accumulates in the form of inert facts.” Literature shows us how to animate facts, and still more how to make them cooperate, to work and dance together toward revelation.

Yet literature can be highly complex. Given its complexity, given all the ways in which poems, plays, and novels resist as well as provoke our desire to know what they mean, the study of literature once again invites the charge of inefficiency. If you just want to know how to make the written word get you a job, make you a sale, or charm a venture capitalist, you don’t need to study the gnomic verses of Emily Dickinson or the intricate ironies of Jonathan Swift. All you need is a good textbook on writing and plenty of practice.

Why then do we really need literature? Traditionally, it is said to teach us moral lessons, prompting us to seek “the moral of the story.” But moral lessons can be hard to extract from any work of literature that aims to tell the truth about human experience—as, for instance, Shakespeare does in King Lear. In one scene of that play, a foolish but kindly old man has his eyes gouged out. And at the end of the play, what happens to the loving, devoted, long-suffering Cordelia—the daughter whom Lear banishes in the first act? She dies, along with the old king himself. So even though all the villains in the play are finally punished by death, it is not easy to say why Cordelia too must die, or what the moral of her death might be.

Joseph Conrad once declared that his chief aim as a novelist was to make us see. Like Shakespeare, he aimed to make us recognize and reckon with one of the great contradictions of humanity: that only human beings can be inhumane. Only human beings take children from their parents and lock them in cages, as American Border Patrol agents did to Central American children two years ago; only human beings burn people alive, as ISIS has done in our own time; only human beings use young girls as suicide bombers, as Boko Haram did 44 times in one recent year alone.

As a refuge from such horrors, literature can offer us visions or at least glimpses of beauty, harmony, and love. They are part of what Seamus Heaney called “the redress of poetry”—compensation for the misery, cruelty, and brutality that human beings ceaselessly inflict on one another. But literature at its most powerful is never just a balloon ride to fantasy, a trip to the moon on gossamer wings. Rather than taking flight from our inhumanity, great literature confronts it even while somehow keeping alive its faith in our humanity. What is the moral of Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved, the story of a formerly enslaved Black woman who killed her own infant daughter to spare her from a life of slavery and sexual exploitation? In a world of merciless inhumanity, can infanticide become an expression of love?

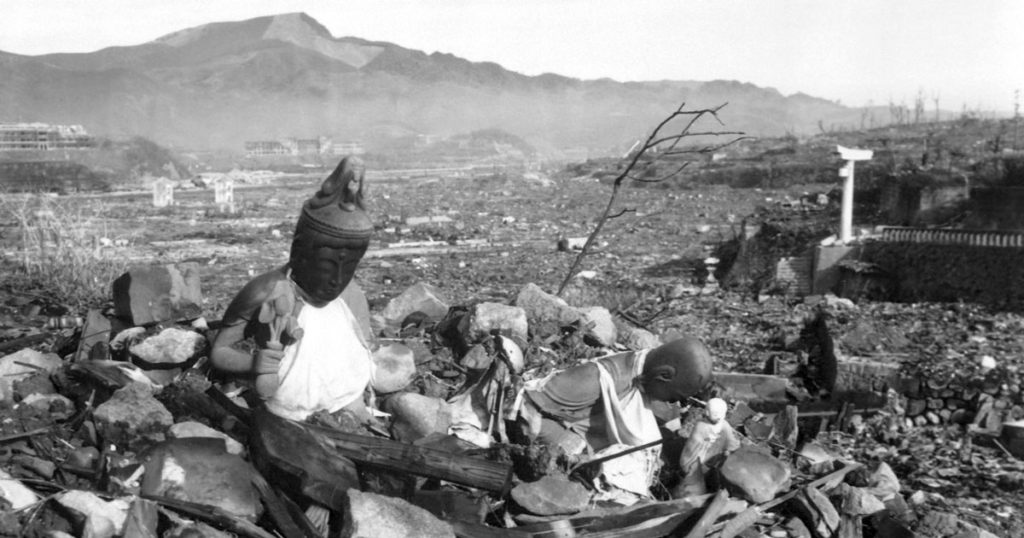

This is the kind of question literature insists on asking. At the heart of the humanities lies humanity, which stubbornly insists on measuring everything in terms of its impact on human life. Seventy-six years ago, J. Robert Oppenheimer midwifed the birth of the most destructive weapon the world had ever seen—a weapon that made America invincible, ended World War II, and saved countless American lives. But the atomic bombs that America dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki incinerated more than 200,000 men, women, and children. That is why Oppenheimer said afterward: “In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

In saying this, Oppenheimer was not just radically unscientific. He was potentially treasonous, disloyal to a government bent on military supremacy above all else. Refusing to join the next heat in the arms race, the development of the hydrogen bomb, Oppenheimer lost his security clearance and spent the rest of his life under a cloud of suspicion.

But his response to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki demonstrates the kind of humanity that the humanities aim to nurture. We need this humanity now more than ever, when the diabolical cruelty of terrorism is compounded by the destructiveness of our very own drone strikes, which too often hit not only the guilty but also the innocent—the victims of “collateral damage,” the human life we sacrifice to our military ends.

We need literature to bear witness to such sacrifices—the lives we take and also the minds we deform in the process of making war. One of those minds is portrayed in a book called Redeployment, a collection of stories about American soldiers in Iraq written by Phil Klay, a veteran U.S. Marine officer. In one of his stories, a lance corporal says to a chaplain, “The only thing I want to do is kill Iraqis. That’s it. Everything else is just, numb it until you can do something. Killing hajjis is the only thing that feels like doing something. Not just wasting time.”

Where is the humanity here? This soldier has just enough left to realize that he has been weaponized, turned into a killing machine. Literature thus strives to speak both for and to whatever shred of humanity may survive the worst of our ordeals. In The Plague, a novel he wrote during the Second World War, Albert Camus symbolically portrays the war as a bubonic plague striking an Algerian city. The story is told by a doctor who struggles—often in vain—to save all the lives he can, though hundreds of men, women, and children will die before the plague has run its course. In the end, he says, this tale records what had to be done and what must be “done again in the never-ending fight against terror and its relentless onslaughts.”

If these words seem uncannily resonant for our time, consider what the doctor says about how the fight against terror must be waged. “Despite their personal afflictions,” he says, it must be waged “by all who, while unable to be saints but refusing to bow down to pestilences, strive their utmost to be healers.”

Having spent trillions of dollars fighting terrorism with bullets and bombs, we need literature and the humanities now more than ever, because they strive to heal, to nurture the most priceless of all our possessions: our humanity.