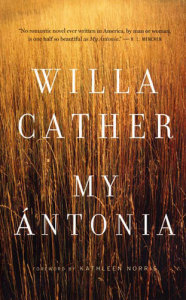

I first read Willa Cather’s My Àntonia when I was in college in Tennessee. I would sit in the sunshine just as the oaks and tulip poplars were coming into leaf and imagine the Great Plains of Cather’s evocation, a landscape so devoid of physical demarcation that its vast sky and endless sea of grass could be terrifying to behold, so bare that its inhabitants might as well be living on bedrock.

Cather’s story begins when young Jim Burden meets Àntonia Shimerda on the train to Black Hawk, Nebraska. We wonder if it is the beginning of a romance. Will these two children grow up exploring the prairieland together only to fall in love years later? For a while, this seems to be the case, but soon they are swept up in the frontier fervor. Newcomers to the land are possessed by the impulse to plow the soil into submission, and as go the grasslands so go Jim and Àntonia’s romantic possibilities.

What makes the novel so slippery is that it is narrated retrospectively. As we learn in the book’s introduction, this is Jim’s story, told from his perspective decades later. His tale is tinged with the regrets and sorrows of middle age, but Cather manages to swing the pendulum between development and hindsight, keeping the book centered like a taproot in the Nebraskan landscape.

The summer after first reading My Àntonia, I went on a Willa Cather binge and discovered her later works, particularly The Professor’s House and Death Comes for the Archbishop, probably her best novels. Cather’s writing is sparse, like the lands she describes. For me, the thrill of reading her comes as much from what she omits as from what she chooses to include. Her prairieland voice can both unnerve and entrance, and the harsh beauty of the book’s scenes haunt me still.