Why 100,000,000 Americans Read Comics

The creator of Wonder Woman makes the case for superheroes—especially female ones

William Moulton Marston, the creator of Wonder Woman, published this essay in our Winter 1943-44 issue. It appears here online for the first time.

Listen to a narrated version of this essay:

American literature has reached in the present day “comics” or adventure strip a zenith of popularity never before achieved in world history by any form of reading matter. Eighteen million comics magazines are sold on the newsstands every month. Since, according to competent surveys, four or five persons read each magazine, we reach the startling total of 70,000,000 or more monthly readers. Research indicates that nearly half these readers are adults.

But monthly comic magazine sales represent only the cream of the story-strip crop. Approximately 1,500,000,000 copies of four- or five-panel comic strips are circulated every week in the daily newspapers. Only two of the nation’s 2,300 sizable dailies—the New York Times and the Christian Science Monitor—are without comics. On Sunday morning some 40,600,000 children read 2,500,000,000 comic strips in more than 50,000,000 comic sections of Sunday newspapers, with far greater concentration than the progeny of our Puritan ancestors read the Bible. If some unlucky youngsters can’t get the funnies away from Dad, or if the younger children can’t read the captions and can’t get Mommie to read them, they turn on the radio and listen to Uncle Don and other professional story-strip readers who broadcast the leading week-end comics features. To be sure, on weekdays it is very tiresome for millions of youngsters to wait until Father brings home the evening paper—so every day several comics continuities are dram the radio. Then, too, at the movies the children see Blondie, Superman, Batman, and other story-strip dramas on the screen. And almost certainly they will see a Walt Disney or some similar animated animal cartoon every time they visit the cinema. The comics have become a seven-day, morning-afternoon-and-evening mental diet for a vast majority of Americans. One hundred million is a very conservative estimate of the total number of men, women, and children who habitually read story strips in the United States today.

This phenomenal development of a national comics addiction puzzles professional educators and leaves the literary critics gasping. Comics, they say, are not literature-adventure strips lack artistic form, mental substance, and emotional appeal to any but the most moronic of minds. Can it be that 100,000,00 Americans are morons? Possibly so; but there seems to be a simpler explanation. Nine humans out of ten react first with their feelings rather than with their minds; the more primitive the emotion stimulated, the stronger the reaction. Comics play a trite but lusty tune on the C natural keys of human nature. They rouse the most primitive, but also the most powerful, reverberations in the noisy cranial sound-box of consciousness, drowning out more subtle symphonies. Comics scorn finesse, thereby incurring the wrath of linguistic adepts. They defy the limits of accepted fact and convention, thus amortizing to apoplexy the ossified arteries of routine thought. But by these very tokens the picture-story fantasy cuts loose the hampering debris of art and artifice and touches the tender spots of universal human desires and aspirations, hidden customarily beneath long accumulated protective coverings of indirection and disguise. Comics speak, without qualm or sophistication, to the innermost ears of the wishful self. The response is like that of a thirsty traveler who suddenly finds water in the desert-he drinks to satiation.

Strange as it may seem, it is the form of comics-story telling, “artistic” or not, that constitutes the crucial factor in putting over this universal appeal. The potency of the picture story is not a matter of modern theory but of anciently established truth. Before man thought in words he felt in pictures. Man still prefers to short-cut his mental processes by skipping the laryngial substitutes and visualizing directly the dramatic situations that rouse his emotions. Eight or nine people out of ten get more emotional “kick” out of seeing a beautiful girl on the stage, the screen, or the picture-magazine page displaying her charms in person, or via camera or artist’s pen, than they derive from verbal substitutes describing her compelling charms. It’s too bad for us “literary” enthusiasts, but it’s the truth nevertheless-pictures tell any story more effectively than words. Modern evidence of this prehistorically established fact is furnished by the amazing success of tabloid picture papers like the New York News, which has attained the largest circulation of any newspaper in the world; the growth of the pictorial weeklies, Life, Look, and a host of successful followers; and, the chief case in point, the amazing vogue of our modern picture-story classic, the comics magazine.

You think, perhaps, as I did before I looked into the matter, that comics continuities are something new in the world of fantasy and fiction. You are wrong; so was I. Mr. M. C. Gaines, a former school principal who originated the comic magazine and is publisher of a large group of these potent periodicals, including “Picture Stories from the Bible,” went back to ages past and dug out some interesting facts about the success of the picture story during the early dawn of civilization. [1] The ancients, as numerous historical monuments attest, recorded their military triumphs as well as their domestic comedies in picture stories. These visual histories were done in shells, lapis lazuli, and pink limestone. We have specimens from Ur produced in 3500 B.C. In that early attempt to laugh and live with all the people through a pictorial medium, two girls were shown in a hair-pulling contest while other panels depicted victorious royal armies conquering and subjecting national enemies. What have we today? The same thing precisely, done with artist’s ink, zinc plates, and a four-color printing process. The new development, accomplishing the ancient purpose, lies merely in the fact that modern mechanical facilities permit comic strip producers to distribute their picture tales to a hundred million people instead of carving them on a stationary stone monument where only a few daring travelers could ever see them. The recreational appeal of picture dramas has always existed; the means of contacting vast populations with these pictorial creations constitutes the real achievement of our present age.

As the technique of picture publication evolved, the art of visual stimulation of mass emotions kept pace. Back in 1521, when the artist Hans Cranach picturized Martin Luther’s Passional Christi und Antichristi, showing the Savior’s humility in rebuking contrast to the pomposity of churchmen, the form of publication was crude indeed and the moral propaganda type of story content fell equally far from the mark of universal appeal. Satire and caricatures of the sins of notorious sinners did a little better as the printing process came into its own at the beginning of the eighteenth century. William Hogarth’s “Rake’s Progress” was a distinct success, though still damned by an overdose of reform motive. Political cartoons then, as now, appealed violently to partisan groups and evoked corresponding scorn from the par ties attacked.

Nothing notable was accomplished in technique for another century, when Wilhelm Busch and some printers got together on a line-drawing proposition that resulted in his famous Sketch Book, and an equally notable volume portraying the undisguised naughtiness of two young devils, “Max and Moritz.” This departure from accepted convention in both art and story content was a long step in the right direction-a step backward, toward the uninhibited, primitive, popular appeal of totem-pole carvings and Egyptian monument pictures along the Nile. The visual form must be simplified to essentials, the emotional response evoked must be instant and universal. When these two requirements are satisfied, it remains only to distribute the published product widely to secure a vast reading audience. Line drawing met the test of simplicity of art form, and childish mischief appealed to the repressed human wish to kick over the traces, smash conventional restraint, and eat forbidden fruit. This cartoon formula, therefore—purveyed to increasing multitudes by accommodating printers—set the pattern for the early stages of our modern comics era. Rudolph Dirks followed precisely the style and story theme of “Max and Moritz” when he began drawing “The Katzenjammer Kids,” first popularized by Hearst papers in I 897 and still among the leading newspaper comic strips.

Roughly, the evolution of comics may be divided into three steps or stages. The first period, from 1900 to 1920, consisted almost entirely of comics that were meant to be comical. The second period, beginning hesitantly with the introduction of pathos and human interest into the continuities of the early twenties, reached its full fruition about 1930 when leading comics frankly stopped trying to be funny and became adventure strips. The third comics period began definitely in 1938 with the advent of Superman and constitutes a radical departure from all previously accepted standards of story telling and drama. Comics continuities of the present period are not meant to be humorous, nor are they primarily concerned with dramatic adventure. Their emotional appeal is wish fulfillment. There is no drama in the ordinary sense, because Superman is invincible, invulnerable. He can leap over skyscrapers, fly through the air and catch air planes, toss battleships around, or repel bullets with his bare skin. Superman never risks danger; he is always, and by definition, superior to all menace.

Superman and his innumerable followers satisfy the universal human longing to be stronger than all opposing obstacles and the equally universal desire to see good overcome evil, to see wrongs righted, underdogs nip the pants of their oppressors, and, withal, to experience vicariously the supreme gratification of the deus ex machina who accomplishes these monthly miracles of right triumphing over not-so-mighty might. Here we find the Homeric tradition rampant—the Achilles with or without a vulnerable heel, the Hector who defends his home town from foreign invaders, wronged Agamemnon who pursues his righteous vengeance with relentless fury, and the wily Ulysses who cleverly accomplishes the downfall of attractive if culpable enemies by the exercise of superhuman wisdom. Homer did very well for himself with the troubadour technique in an age when pictures had to be painted by imagination. But M. C. Gaines, who perceived the Homeric inheritance of Siegal and Shuster and who turned the comics magazine into an illuminated vehicle for their dramaless but wish-fulfilling Superman tales, did far better—for himself and for his associates and followers. There can be little question, as this article goes to press, that the wish-fulfillment period of picture-story evolution is reaching new heights of reader interest, popular favor, publishers’ profits, and—I say this thoughtfully—moral educational benefits for the younger generation.

If children will read comics, come Hail Columbia or literary devastation, why isn’t it advisable to give them some constructive comics to read? After all, 100,000,00 Americans can’t be wrong—at least about what they like. But the more decisive argument is psychological. What life-desires do you wish to stimulate in your child? Do you want him (or her) to cultivate weakling’s aims, sissified attitudes? Your youngster may not inherit the muscles to do 100 yards in nine seconds flat, or make the fullback position on an All-American football team. But if not, all the more reason why he should cultivate the wish for power along constructive lines within the scope of his native abilities. The wish to be super-strong is a healthy wish, a vital, compelling, power-producing desire. The more the Superman-Wonder Woman picture stories build up this inner compulsion by stimulating the child’s natural longing to battle and overcome obstacles, particularly evil ones, the better chance your child has for self advancement in the world.

Certainly there can be no argument about the advisability of strengthening the fundamental human desire, too often buried beneath stultifying divertisements and disguises, to see good overcome evil. “Happy” endings are shown in the new comics as products of superhuman efforts to help others—not as mere happenstances mysteriously obeying the “Pollyanna” rule that “everything always comes out all right in the end.” The moral force of this new type of story teaching is stronger far than the older appeal to self-interest. “Be good and you’ll be happy” is a difficult idea to sell. Children don’t believe it, even in stories. Nor are they greatly impressed by its converse: “If you’re bad you’ll get punished.” They qualify the latter precept by adding, “If you are caught.” And when a religious teacher resorts to the next world for a flavor of inevitability, the averagely bright child in this cynical age remarks, “But how do you know what happens in the next world?” Heaven and hell are a long way off, psychologically, from a child’s today. But heroics are their daily bread.

Feeling big, smart, important, and winning the admiration of their fellows are realistic rewards all children strive for. It remains for moral educators to decide what type of behavior is to be regarded as heroic. Shall we teach our children that the heroic thing, the deed for which they will attain desired kudos, is killing enemies and conquering their neighbors, à Ia Napoleon,

Hitler, Genghis Khan, and others of their ilk? Or shall we make the great stunt in a child’s mind the protection of the weak and the helping of humanity? The Superman-Wonder Woman school of picture-story telling emphatically insists upon heroism in the altruistic pattern. Superman never kills; Wonder Woman saves her worst enemies and reforms their characters. If the incredible barrage of comic strips now assaulting American minds establishes this new definition of heroics in the thought reflexes of the rising generation, it will have been worth many times its weight in pulp paper and multicolored ink.

Comics have many faults. Some of their most glaring misdemeanors have been curbed; other assaults on culture and good taste go merrily on. My first sortie into the comics field was in the role of reformer. I was retained as consulting psychologist by comics publishers to analyze the present shortcomings of monthly picture magazines and recommend improvements. An advisory board of educators was formed for the “Superman-D. C.” group of publications, including such outstanding authorities as Professor W. W. D. Sones, Director of Curriculum Study at the University of Pittsburgh; Professor Robert Thorndike of Teachers College, Columbia; and Dr. C. Bowie Millican, Professor of English Literature at New York University. The active efforts of these and others and the cooperation of the publishers, headed by M. C. Gaines and his associates, have raised considerably the standards of English, legibility, art work, and story content in some twenty comics magazines totaling a monthly circulation of more than 6,000,000. Picture stories have proved effective in teaching school subjects, notably English, which formerly was the most frequently criticized feature of the strips. We have inaugurated the policy of introducing into continuities a certain percentage of words which are above the average child-reader level, with the result that children soon determine the meanings and add these new words to their vocabularies. Excerpts from Superman have been used successfully in teaching English in the public schools, notably in a junior high school at Lynn, Massachusetts, where a special Superman workbook was compiled by a progressive young English instructor. These developments are only in their early stages, with tremendous possibilities indicated by initial experiments.

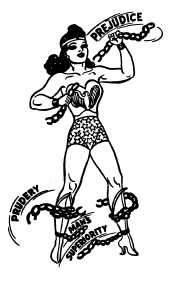

The most radical departure from previously accepted rules of picture-story content resulted from an early recommendation of mine to the publishers. It seemed to me, from a psychological angle, that the comics’ worst offense was their blood-curdling masculinity. A male hero, at best, lacks the qualities of maternal love and tenderness which are as essential to a normal child as the breath of life. Suppose your child’s ideal becomes a superman who uses his extraordinary power to help the weak. The most important ingredient in the human happiness recipe still is missing—love. It’s smart to be strong. It’s big to be generous. But it’s sissified, according to exclusively masculine rules, to be tender, loving, affectionate, and alluring. “Aw, that’s girl’s stuff!” snorts our young comics reader. “Who wants to be a girl?” And that’s the point; not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, power. Not wanting to be girls they don’t want to be tender, submissive, peaceloving as good women are. Women’s strong qualities have become despised because of their weak ones. The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of a Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman. This is what I recommended to the comics publishers.

My suggestion was met by a storm of mingled protests and guffaws. Didn’t I know that girl heroines had been tried in pulps and comics and, without exception, found failures? Yes, I pointed out, but they weren’t superwomen—they weren’t superior to men in strength as well as in feminine attraction and love inspiring qualities. Well, asserted my masculine authorities, if a woman hero were stronger than a man, she would be even less appealing. Boys wouldn’t stand for that; they’d resent the strong gal’s superiority. No, I maintained, men actually submit to women now, they do it on the sly with a sheepish grin because they’re ashamed of being ruled by weaklings. Give them an alluring woman stronger than themselves to submit to and they’ll be proud to become her willing slaves!

M. C. Gaines listened to our arguments for a while. Then he said: “Well, Doc, I picked Superman after every syndicate in America turned it down. I’ll take a chance on your Wonder Woman! But you’ll have to write the strip yourself. After six months’ publication we’ll submit your woman hero to a vote of our comics readers. If they don’t like her I can’t do any more about it.” That was fair enough. I wrote Wonder Woman. I found an artist—Harry Peter, an old-time cartoonist who began with Bud Fischer on the San Francisco Chronicle and who knows what life is all about—and with Gaines’ helpful cooperation we created the first successful woman character in comics magazines. After five months the publishers ran a popularity contest between Wonder Woman and seven rival men heroes, with startling results. Wonder Woman proved a forty to one favorite over her nearest male competitor, capturing more than 80 per cent of all the votes cast by thousands of juvenile comics fans. The credit is all Wonder Woman’s—I mean the wonder which is really woman’s when she adds masculine strength to feminine tender ness and allure. The kids who rated Wonder Woman tops in an otherwise masculine galaxy of picture story stars weren’t voting for a clever script writer (of that I assure you!), nor were they expressing a preference for Harry Peter’s drawing, understanding as it is. They were saying by their votes, “We love a girl who is stronger than men, who uses her strength to help others and who al lures us with the love appeal of a true woman!”

So there’s the latest formula in comics—super strength, altruism, and feminine love allure, combined in a single character. Forget the crudities of plot, drawing, printing, and color work-or, rather, regard them as essential simplifications in constructing an emotional stimulus with universal appeal. Then consider our modern facilities for making cheap paper from trees, printing millions of pages at lightning speed in natures four primary colors, and the familiar miracles of transportation which distribute hundreds of thousands of picture-story books across a continent in a few hours time. Add these products of human progress together and you can understand, without straining a sinew of your imagination, the astounding consumption of America’s most popular mental vitamin, the wish-fulfilling picture story.