11 Culinary Books with Words to Savor

Food writing so good, you can practically taste it

Weeks of quarantine have forced even the most inexperienced home cooks to put their skills to the test, as evidenced by near-empty grocery store shelves across the country. Here at the Scholar, we’re revisiting our favorite food writers, finding solace in their reminders that anyone can cook good food— and that good prose is the perfect accompaniment to any dish.

Life Is Meals: A Food Lover’s Book of Days by James and Kay Salter

James Salter was a Korean War fighter pilot and an award-winning novelist whose many books—including his 1967 novella, A Sport and a Pastime—earned him the reputation of being a “writer’s writer.” But he and his wife, Kay, were also avid cooks and entertainers. His 2010 book, Life Is Meals: A Food Lover’s Book of Days, is a sumptuously illustrated companion to the gustatory year. For each calendar day, Salter offers history, anecdotes, examples of proper mealtime etiquette, culinary tricks of the trade, and recipes (Creamed Chipped Beef, anyone?) Read it in preparation for that dreamed-of day when you can once again invite company for dinner. —Bruce Falconer

The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book by Alice B. Toklas

One Thanksgiving holiday a few years ago, we rented a house in rural Rappahannock County, Virginia, and spent two lovely days in solitude. The time was memorable not only for the turkey dinner and the wine—two bottles of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, an excellent Madeira, and a bottle of my favorite Rioja—but also because I read Alice B. Toklas’s charming memoir documenting the author’s life in France with Gertrude Stein. The likes of Picasso, Matisse, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald make cameos, though the most memorable characters are often the many cooks Toklas and Stein came to know. One of those cooks, an Austrian identified only by the first name Frederich, had worked in the kitchen of the Hotel Sacher in Vienna and gave Toklas his recipe for Sacher Torte. I made this cake the day after Thanksgiving, and, as I recall, it came out splendidly. —Sudip Bose

Sacher Torte

Cream ½ cup butter; gradually add 1 cup sugar, the grated peel of 1 lemon, 4 oz. melted chocolate, the yolks of 6 eggs; fold in the beaten whites of 6 eggs and 3 tablespoons flour. Butter and flour a flat cake pan and bake for 40 minutes in a 325° oven. Let cool in pan. When perfectly cold, cut in half and spread the following mixture between the two layers.

2 ozs. chocolate melted, to which add 1 teaspoon powdered coffee dissolved in ½ cup hot water. When perfectly smooth beat in 2 yolks of eggs. Beat 1 cup heavy cream sweetened with 3 tablespoons icing sugar. Add first mixture to the whipped cream. Cover the cake with apricot jelly or strained apricot jam and ice with chocolate icing.

How to Cook a Wolf by M.F.K. Fisher

Difficult though it may be to pick just one book by the godmother of American food writing, I have always loved How to Cook a Wolf best. Published in 1942 and written in the midst of World War II, the wolf of the title is the hunger of wartime, which Fisher recommends keeping at bay with clever cooking, wit, and an eye to the “blackout shelf.” The book spans my feelings in quarantine, with chapters both on “How to Keep Alive”—for “the pressing problem of how to exist the best possible way for the least amount of money”—and how to savor roast pigeon.—Stephanie Bastek

Simple Cooking by John Thorne

This book, which grew out of a series of newsletters that John Thorne mailed to subscribers from his house in coastal Maine, is a revelation. It extolls the pleasures of unpretentious home cookery; indeed, I can think of few other writers who can elevate a humble bowl of porridge or cup of cocoa to such exalted heights. I am especially fond of his meditation on that most unassuming of American classics, macaroni and cheese. Thorne writes at length about his method—selecting the block of Wisconsin cheddar for its texture and color, then grating it (“the cheese slips into shreds, heaps into a generous pile, a whole pound of it”), and later checking the pasta for doneness (it “must be caught at just the right moment, still with a tiny bit of ‘spine’ or crunch, so it can finish its cooking absorbing the taste and savor of the sauce”). Thorne’s writing appeals to every one of the senses, and you quickly begin to realize that this simple cook is, in truth, an artist. I find his approach all the more necessary in our present age, when every home cook, seduced by the frenetic lunacy of so much awful food television, aspires to plate a Tuesday dinner in the manner of a three-Michelin-star chef. Preparing macaroni and cheese, however, does not pose a “true challenge to the good cook,” Thorne writes. “If kudos are wanted, they must be earned making something else. But mastery of the difficult is only one of the rewards of cooking, and it is worth remembering now and again that there is a humbler gift a dish can give the cook: the pleasure of its company.”—Sudip Bose

Macaroni and Cheese

(Serves 4 to 6)½ pound elbow macaroni

4 tablespoons (1/2 stick) butter, cut into bits

Dash Tabasco sauce

1 12-ounce can evaporated milk (or use whole milk mixed with a little cream)

1 pound sharp cheddar cheese, grated

2 eggs, beaten

1 teaspoon dry mustard, dissolved in a little water

Salt and freshly ground pepperPreheat oven to 350°F. Boil the macaroni until just barely done in salted water. Drain and toss with the butter in a large, ovenproof mixing bowl. Mix the Tabasco into the evaporated milk. Reserving about 1/3 cup, stir the milk into the macaroni, then add three quarters of the cheese, the eggs, and the mustard. When well combined, season to taste with salt and pepper, and set the bowl directly in the oven. Every five minutes, remove it briefly to stir in some of the reserved cheese, adding more evaporated milk as necessary to keep the mixture moist and smooth. When all the cheese has been incorporated and the mixture is nicely hot and creamy (which should take 20 minutes, all told), serve it at once, with a plate of toasted common crackers to crumble over.

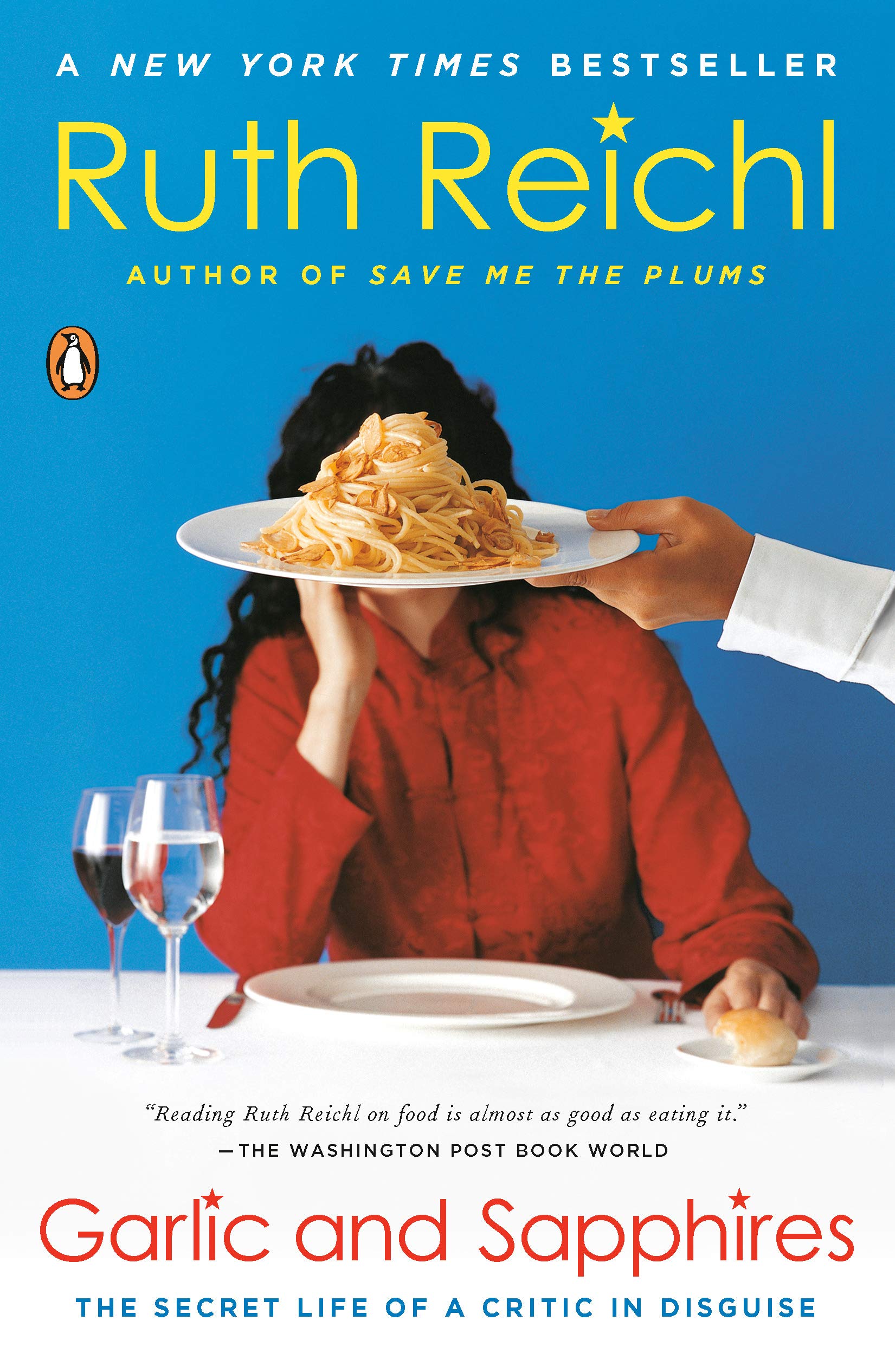

Garlic and Sapphires: The Secret Life of a Critic in Disguise by Ruth Reichl

I heartily recommend any of Ruth Reichl’s memoirs— I never tire of her warm, witty voice and reverent meal descriptions— but the one I return to most is Garlic and Sapphires: The Secret Life of a Critic in Disguise, a funny and poignant reflection on her six-year tenure as The New York Times’s restaurant critic. Reticent about her sudden celebrity, Reichl takes to dining out on the job in elaborate disguises, an experiment that proves successful—her in-character reviews cement her as one of the nation’s most entertaining, if controversial, food writers— but eventually leads her to wonder if the costumes have swallowed up her real life. Reprinted reviews and original recipes, from matzo brei to Reichl’s son’s favorite vanilla cake, help to make each chapter of this book even more of a treat than the last. —Jayne Ross

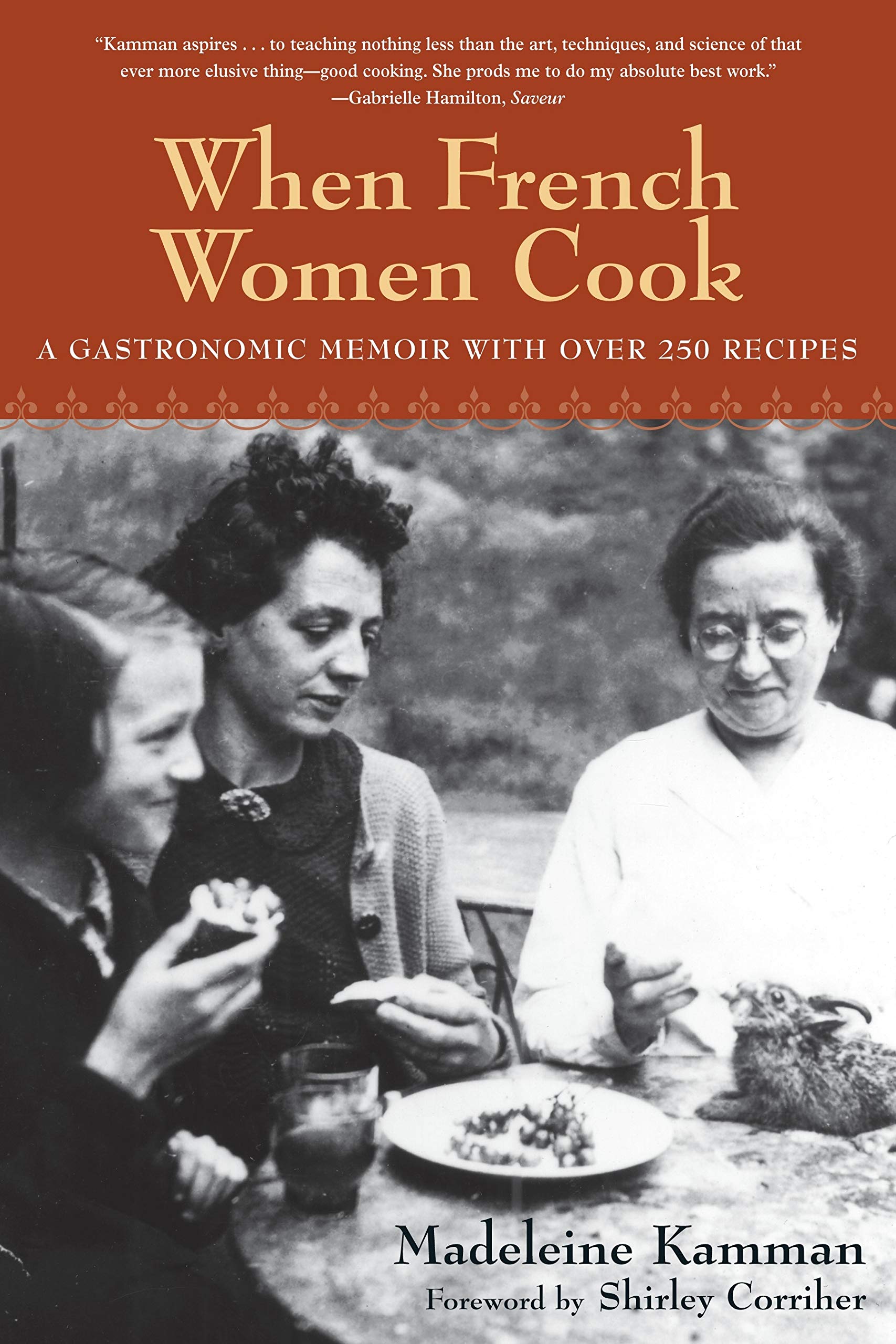

When French Women Cook by Madeleine Kamman

Born in Paris in 1931, Kamman was the grande dame of French cooking teachers in America, a towering and uncompromising figure who, as much as anyone else, was responsible for helping to lift the cuisine of this country in the last decades of the 20th century. All her books are worth seeking out, but this memoir, about her experiences in the kitchens of eight French cooks—each representing a different region of the country—is especially compelling. One of these women, Victoire, lived in the Auvergne, and Kamman got to know her during the summer of 1939, a time that, despite ominous historical circumstances, the author remembers as magical. Upon entering Victoire’s stone house, in the village of La Vachellerie, Kamman encountered

a world that I had no idea existed. There was a huge chimney, black with the smoke of centuries, in which a pine needle and wood fire burned bright. And something mysterious, something I had never seen before—a bread oven. … There was a table covered with an electric blue and white checkered tablecloth loaded with fresh bread slices, butter, rich and yellow, a side of bacon, several saucissons, and a huge pot of café au lait. The room smelled of everything, smoke, bacon, garlic, cows, cheese and lentils cooking in a huge, iron pot buried in the ashes of the hearth.

Victoire’s tomato salad with verjus (the pressed juice of unripened grapes)—not so much a recipe as an assemblage of ingredients—is a dish to dream about until the sweltering days of August arrive. Note that although you can make your own verjus, and Kamman provides Victoire’s recipe, very good bottles can be ordered online. I am partial to the version made by the winemakers at Navarro vineyards in Mendocino.—Sudip Bose

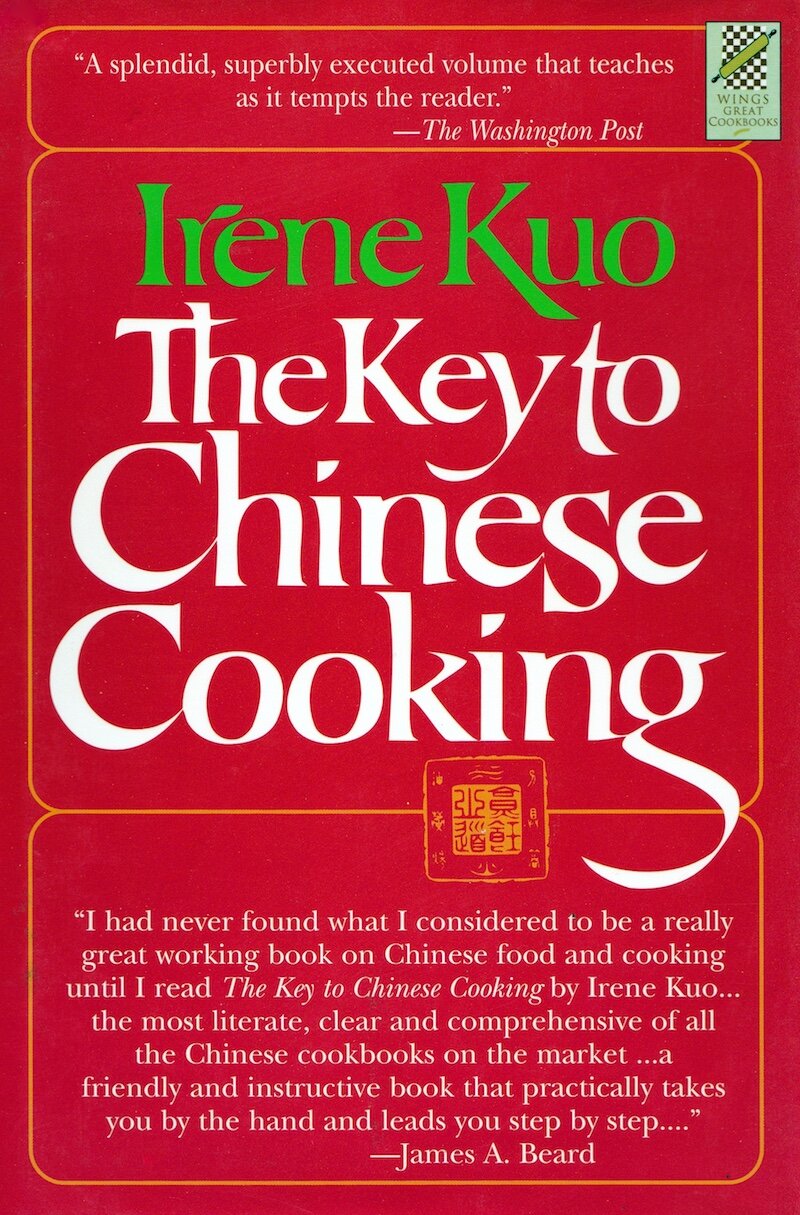

The Key to Chinese Cooking by Irene Kuo

I stumbled upon this book last summer, and immediately fell down a rabbit hole of “stir-frying, red-cooking, pansticking, slithering, exploding, plunging, purifying, smothering, mating, nestling, capturing, choking, flavor-potting, light-footing, sizzling, rinsing, scorching, drowning, wine-pasting, and intoxicating”—all the techniques that Irene Kuo, the glamorous proprietor of two midcentury Manhattan restaurants, promised to teach me in 500 pages. Kuo is quite the cook and quite the writer—here’s a taste from her introduction: “the Chinese have had both the dire need to experiment on all things edible for sheer survival and the leisure of prosperity to perfect their cooking techniques for sensual enjoyment. They eat boiled bark, weeds, and roots when there is nothing else; they eat shallow-fried transparent prawns from preference, jasmine blossoms out of poetic sentiment, and wine-braised camel’s hump from blatant extravagance.” —Stephanie Bastek

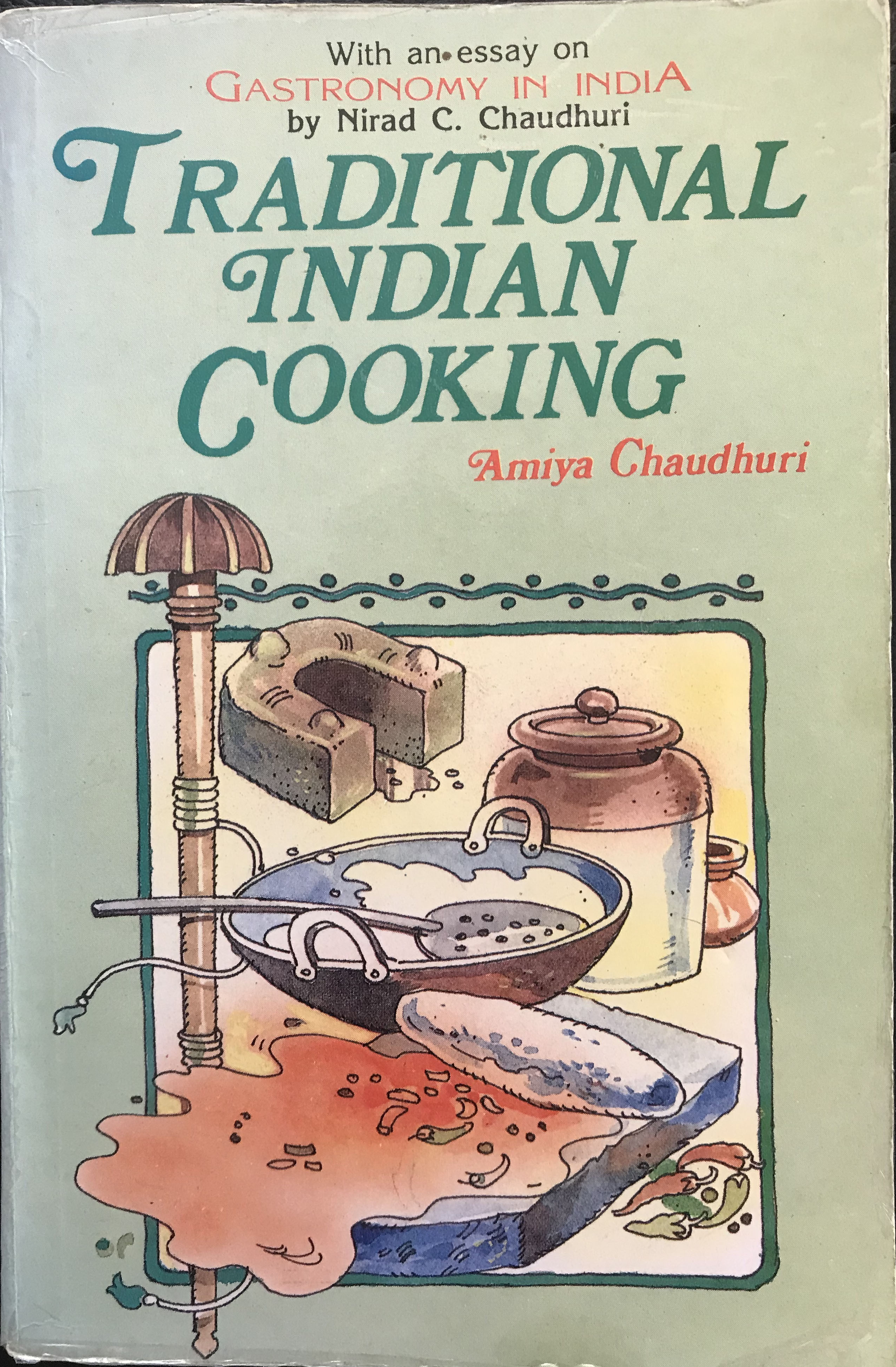

Traditional Indian Cooking by Amiya Chaudhuri

Amiya Chaudhuri’s slim volume has the added bonus of an introductory essay by her husband, the redoubtable and prolific Nirad C. Chaudhuri, whose Autobiography of an Unknown Indian is a masterpiece of the genre. Like that work, his “Gastronomy in India” is patrician, elegant, uncompromising, and informed by deep learning. In providing a brief history of both Muslim and Hindu haute cuisine, Chaudhuri focuses on the food traditions of the aristocratic Bengali households of an earlier era, emphasizing the importance of rice, lentils, fish, and meat. As for sweets, for which Bengalis have always had a bottomless appetite, Chaudhuri tells a story about a visit from his friend Count Stanislas Ostroróg, France’s ambassador to India in the 1950s, and a ubiquitous Bengali dessert called Sandesh, made with soft homemade cheese and sugar:

[Ostroróg] told me that no sweets were ever served with the famous white wine of Bordeaux—Chateau Yquem; only peach and cream was taken with it. But when he came to dine at my house in Delhi my wife gave him a kind of Sandesh which was her specialty, and I gave him a Chateau Yquem, 1947. He told me afterwards that the sweet perfectly matched the wine.

A 1947 Chateau d’Yquem could set you back some $20,000 these days, depending on its condition, so I’ll have to take his word for it. Let me suggest another recipe, Amiya Chaudhuri’s version of Moghlai paratha, a savory pastry filled with egg and minced green chilies. This is also one of my mother’s specialties, a staple of Sunday lunches when I was growing up, and if I had to pick a last meal, it would be four or five of these parathas, followed by a plate of my mother’s catfish curry and rice. One important note: I generally consider commercial ketchup an abomination, but I’ll happily make an exception when eating Moghlai paratha. It’s a combination I relished as a child, one that I haven’t been able to outgrow. —Sudip Bose

Moghlai Paratha

Plain flour, 250 grams

Salt, ½ teaspoon

Ghee, 1 cup

A little water

Eggs, 2

Onion, 1 (small)

Green chili, 1 (small, optional)

Salt and pepper, to tasteChop onion and green chili. Whisk the eggs in a bowl. Mix in chopped onion and green chili, salt and pepper. Set on one side. Sift together the flour and salt. Rub in the ghee. With a little water mix to a soft dough. Divide the dough into medium-sized balls.

Roll out each ball into a circle, and put on a shallow plate. Using a large spoon, put some of the whisked egg mixture into the middle of the rolled dough. Make four folds and close up. Lift each one very carefully onto a hot shallow frying pan and fry one by one on both sides, spreading ghee around the paratha, until golden brown.

Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking by Marcella Hazan

She might lack the literary flair of Elizabeth David, A.J. Liebling, or M.F.K. Fisher as they write about French cuisine, but Marcella, as she is known to her devotees, wrote about Italian cooking with a simplicity appropriately matching the recipes themselves. Her brief introductions to those recipes always argue for authenticity and straightforwardness, and you could count on her for observations such as, “There is nothing inherently crude about tomato sauce” or “Pesto may have become more popular than is good for it.” She is most famous for her tomato sauce recipe, which involves three ingredients plus salt. It was published on the front page of The New York Times along with her obit when she died in 2013. –Robert Wilson

Tomato Sauce with Onion and Butter

2 pounds fresh or 2 cups canned plum tomatoes

5 tablespoons butter

1 medium onion, peeled and halved

SaltPut the ingredients in a saucepan and simmer for 45 minutes. Toss the onion.

“Meals of Peace and Restoration” by Jim Harrison

Jim Harrison’s food columns in Men’s Journal (and later in Esquire) were vivid, hilarious, strong-willed, hot-tempered, and wise—as memorable as his fiction and poetry. Harrison cooked passionately, ate extravagantly, and drank like a certain Olympian god. “Reach into your memory and come up with what restored you,” Harrison writes, “what helped you recover from the sheer hellishness of life, what food actually regenerated your system, not so you can leap tall buildings but so you can turn off the alarm clock with vigor”—sound advice for our own worrying times. In “Meals of Peace and Restoration” (which appears in the collection The Raw and the Cooked: Adventures of A Roving Gourmand), Harrison offers not a recipe but a prescription for what to eat when feeling less than whole:

[F]or clinical depression you must go to Rio to a churrascaria and eat a roast sliced from the hump of a Zebu bull; also try the feijoada, a stew of black beans with a dozen different smoked meats, including ears, tails, and snouts. For late-night misty boredom, go to an Italian restaurant and demand the violent pasta dish known as puttanesca, favored by the whores of Rome. After voting, eat collard greens to purge you of free-floating disgust. When trapped by a March blizzard, make venison carbonnade, using a stock of shin bones and the last of the doves. If it is May and I wish to feel light and spiritual, I make a simple sauté of nuggets of sweetbreads, fresh morels, and wild leeks, the only dish, so far as I know, that I have created.

In this spirit, I have been trying to combat the spiritual malaise of the moment by eating as well as I can: venison stew, duck confit and lentils, grilled quails and red cabbage, three-egg omelets, butter-and-radish sandwiches, fried rabbit legs and buttermilk biscuits, seared scallops on grits, kedgeree, slow-roasted pork shoulder … All have provided much-needed pleasure and sustenance during these past two months, though the most restorative thing I have cooked, by far, has been a big bowl of greens (radish and turnip tops, spinach, curly kale), with bits of andouille sausage and a diced onion sautéed in duck fat. The pot simmered for at least an hour, by which time the greens had become silky and the pot liquor irresistibly sweet. I’d like to think that Harrison would have approved.—Sudip Bose

Cooking Wild Game by Frank G. Ashbrook and Edna N. Sater

Another rare bookstore find! I can’t say that I’ve cooked anything from this yet, but every once in a while, when the quarantine blues hit me, I start dreaming of some of these recipes and thinking, well, hey, at least we’re not cooking roasted raccoon, opossum with tomato sauce, or woodchuck pie epicure. Yet. —Stephanie Bastek