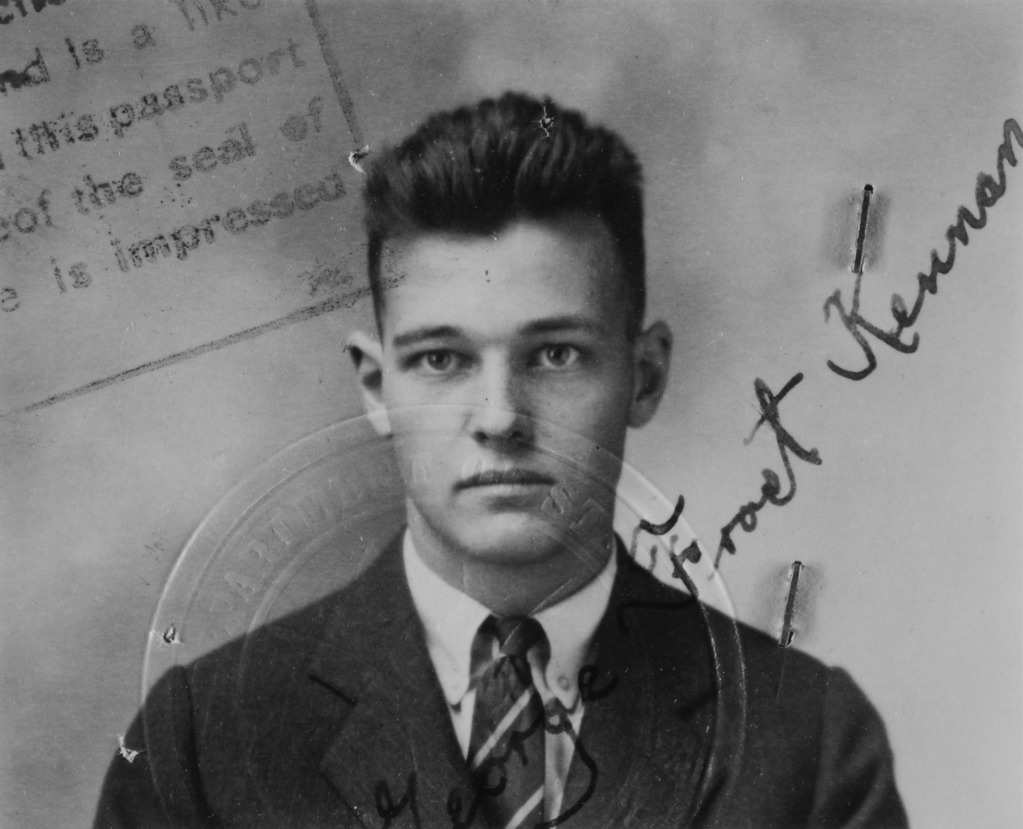

George F. Kennan: An American Life, By John Lewis Gaddis, Penguin Press, 784 pp., $39.95

George Kennan was the J. Alfred Prufrock of American diplomacy—acutely observant, toxically self-absorbed, and to borrow T. S. Eliot’s words, “full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse; / At times, indeed, almost ridiculous— / Almost, at times, the Fool.” Stress-fueled ulcers would periodically compel him to take weeks or months of convalescence. Several times he tendered, and then rescinded, his resignation from the Foreign Service. Bureaucratic setbacks or unexpected foreign developments would provoke him to all but reverse his positions. His love-hate relationship with his own country would plunge him into alienation and despair.

Yet Kennan (1904-2005) was also the greatest American strategist of the 20th century. Not only did he conceive the now-totemic Marshall Plan and the policy of containment that guided the United States through the Cold War, but he also inaugurated the study of grand strategy at the National War College, created the Policy Planning Staff at the State Department, and helped define the realist school of foreign policy thinking. Outside government, he was an award-winning historian, a sometimes hugely influential gadfly-cum-prophet, and a friend and colleague to intellectual giants such as Isaiah Berlin and J. Robert Oppenheimer, his boss at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton, New Jersey.

John Lewis Gaddis, the renowned Yale history professor, has been at work on this book since Kennan agreed to cooperate with him in 1981. George F. Kennan: An American Life draws on 12 boxes of Kennan’s diaries (part of 330 boxes of his papers at Princeton University), hundreds of published and unpublished works, and nearly 50 interviews Gaddis conducted with Kennan and his family, friends, and colleagues. But Gaddis also labored under the burden of comparison with Kennan’s own eloquent writing about his life (the first volume of Kennan’s memoirs won a Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award). He wisely doesn’t try to match what he calls Kennan’s “epic sentences” or his lyrical descriptive powers. Still, he has written a monumental and rewarding book, one that brings to life a defining era in American diplomacy and connects the flesh-and-blood Kennan with the giant shadow he still casts.

Kennan’s mother died shortly after he was born, a loss that left him, in his own words, “scarred for life” in ways that would affect his emotional balance and his relationships with women. But his upbringing in Milwaukee, Gaddis observes, was otherwise “cheerfully unremarkable”: the son of an upright Presbyterian tax attorney, he was bookish at an early age, spent summers at a lake house, and attended military school. This midwestern idyll became a dream vision of America to which the country, in Kennan’s eyes, often subsequently failed to live up. An admirer of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s work, Kennan was likewise drawn to Princeton and shared some of his literary idol’s insecurities and resentments (Kennan would miss his 25th reunion because he didn’t have the $75 needed to register). He graduated 83rd in the Class of 1925, out of 219 students.

The next year Kennan joined the Foreign Service, and the routine of his junior officer years offer one tortured twist, when he almost resigns to get married, then abandons that plan after the engagement is broken off. He subsequently wrote to his sister, “I will probably never be vastly admired; I shall never achieve much personal dignity.” This sort of sad-sackery becomes a running theme in Kennan’s life and Gaddis’s book, as do Kennan’s bilious rants about his fellow citizens: he wrote in another letter, for instance, that if only Americans “could have their toys taken away from them, be spanked, educated and made to grow up, it might be worthwhile to act as a guardian for their foreign interests.” Gaddis argues that Kennan’s character is best thought of as “triangular, held taut by tension along each of its sides”: “professionalism,” “personal anguish,” and “cultural pessimism” about his own society. But happily for the reader, he chooses to focus more on the traits themselves than on fitting them into this contrived geometry.

Kennan’s rendezvous with Russia, the country and culture that would become his lodestone, came in the aftermath of his first near-resignation. Inspired partly by the Russian travels of his relative and namesake, the explorer and journalist George Kennan, he took up the study of Russian in Riga and Berlin (the United States then had no ties with the new Bolshevik state). A demonstrably keen observer and adept linguist, Kennan was tapped by Ambassador William C. Bullitt to help set up the U.S. embassy in Moscow after the opening of diplomatic relations in 1933. (In a useful counterpoint to Kennan’s image as a Big Thinker, Gaddis reminds his readers that both in Moscow and later, as the temporary leader of Americans interned in Germany during World War II, Kennan proved himself also to be a hard-driving, effective administrator.) Despite the rewards of travel, cultural discovery, and diversions like going with Harpo Marx to watch The Cherry Orchard (no record exists of their conversation), the pressures and privations of diplomatic life in a police state took their physical toll, forcing Kennan’s medical evacuation from Moscow, in 1935, and his absence for almost a year.

Fittingly, Gaddis devotes much attention to the evolution of Kennan’s views on Russia through his midcareer postings, culminating in two of his most famous and influential writings: the “Long Telegram”—at just over 5,000 words, then the longest telegram in the State Department’s history—sent from Moscow on February 22, 1946, and “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” his article for the July 1947 issue of Foreign Affairs, under the pen name “X.” Laying out the challenge posed to the United States by the Soviet Union “in clear prose with relentless logic,” as Gaddis puts it, Kennan advocated a measured response that “became the conceptual foundation for the strategy the United States—and Great Britain—would fol- low for over four decades.” He expanded on his thinking in his Foreign Affairs piece, which began as a report for Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on the “Psychological Background of Soviet Foreign Policy.” In it he argued that “Soviet power … bears within it the seeds of its own decay, and … the sprouting of these seeds is well advanced,” and that therefore the United States should adopt “a policy of firm containment, designed to confront the Russians with unalterable counter-force at every point where they show signs of encroaching upon the interests of a peaceful and stable world.” After The New York Times reported on the article, observes Gaddis, Mr. X became more conspicuous than anonymous. Not everyone was an admirer. Fearing that Kennan’s strategy was both risky and costly, the columnist demigod Walter Lippmann called it a “strategic monstrosity”; Soviet propagandists, meanwhile, denounced Kennan, one calling him a “cannibalistic hyena.”

Yet barely had the idea of “containment” sprung from Kennan’s brow before it took on a form that its creator would forever regret. Other more powerful, more supple U.S. policymakers gave his policy a militaristic and aggressive cast, using it to justify everything from a spiraling nuclear arms race to the war in Vietnam. As Gaddis writes, “Even after the Cold War had ended and the Soviet Union was itself history, Kennan regarded the ‘success’ of his strategy as a failure because it had taken so long to produce results, because the costs had been so high, and because the United States and its Western European allies had demanded, in the end, ‘unconditional surrender.’ ”

Part of the problem was Kennan’s disdain for the tug-and-pull of democracy—an aversion that caused more politically seasoned superiors, such as Ambassador Averell Harriman and Secretary of State Dean Acheson, to regard Kennan’s recommendations as utopian and impractical. By the end of 1948, observes Gaddis, Kennan was “a beleaguered and increasingly bypassed oracle.” His recurring diatribes against his own society, which reached something of a crotchety peak during the 1960s and 1970s, were also a reminder that in many ways, Kennan understood the Soviet Union better than he did the United States. And he was not capable of compartmentalizing his emotional troubles: indeed, “one of Kennan’s most striking characteristics as a diplomat, as a strategist, and as a policy planner was an inability to insulate his job from his moods.” Or as his friend Isaiah Berlin put it, “He doesn’t bend. He breaks.” This flaw manifested itself in one of the Cold War’s greatest diplomatic gaffes, when Kennan, increasingly frustrated by the hostility and isolation he encountered in Moscow as U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, publicly compared the atmosphere there to Nazi Germany. The Soviets declared him persona non grata, and Kennan soon retired from the State Department.

Except for a stint as ambassador to Yugoslavia during the Kennedy administration, Kennan spent the rest of his life at the Institute for Advanced Study, winning plaudits for his history writing and stirring the pot with pronouncements on foreign policy issues or, less judiciously, on the “sickly secularism” of modern American life. Senator J. William Fulbright credited Kennan’s 1966 testimony against U.S. policy in Vietnam with making “it respectable to question, if not to oppose, the war.” Upon winning the Albert Einstein Peace Prize in 1981, Kennan argued for a 50 percent cut in superpower nuclear arsenals—a call that Gaddis says helped shift the Reagan administration’s arms control policies toward reductions. In April 1989, the 85-year-old Kennan’s two-and-a-half-hour Senate testimony on Gorbachev’s reforms brought an unprecedented standing ovation. He published his last book, a family history, in 1996, and nine years later died in his own bed at the age of 101.

Except for a stint as ambassador to Yugoslavia during the Kennedy administration, Kennan spent the rest of his life at the Institute for Advanced Study, winning plaudits for his history writing and stirring the pot with pronouncements on foreign policy issues or, less judiciously, on the “sickly secularism” of modern American life. Senator J. William Fulbright credited Kennan’s 1966 testimony against U.S. policy in Vietnam with making “it respectable to question, if not to oppose, the war.” Upon winning the Albert Einstein Peace Prize in 1981, Kennan argued for a 50 percent cut in superpower nuclear arsenals—a call that Gaddis says helped shift the Reagan administration’s arms control policies toward reductions. In April 1989, the 85-year-old Kennan’s two-and-a-half-hour Senate testimony on Gorbachev’s reforms brought an unprecedented standing ovation. He published his last book, a family history, in 1996, and nine years later died in his own bed at the age of 101.

Kennan’s life was so rich, and so richly documented, that to encompass it in even 700 pages is itself a challenge—one that Gaddis meets. True, he had the advantage of letting Kennan do most of the talking, but his own crisp writing keeps the book moving at a good clip. And while sympathetic to his subject, Gaddis rightly takes him to task for his professional failings, including Kennan’s inability to recognize Ronald Reagan’s role in bringing the Cold War to a close. (On the other hand, Gaddis’s own sympathetic writing elsewhere about George W. Bush’s strategic thinking must have curled Kennan’s last white hairs.) But the book is less satisfying on a personal level: at several points, Kennan’s diary hints at dramatic domestic crises (including one that might trigger Soviet blackmail) that Gaddis does little to explore—something that he surely could have cleared up in one of his interviews with Kennan or his Norwegian wife, Annelise. But Gaddis seems to have been too much the diplomatic historian to go there. And Annelise herself, credited by Gaddis as the paramount steadying influence on Kennan during their seven-decade marriage, has only a slight presence.

But the book’s flaws, like those of its subject, are forgivable: it seems destined to be the defining work about the man whose strategic insight enabled the United States to steer between Soviet domination and global conflagration. Once, worried about Kennan’s intensity as a young boy, an aunt told him to “stop thinking for a little while.” Fortunately for his country, he didn’t.