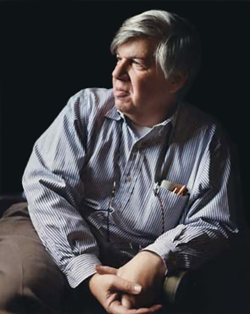

Photo by Kathy Chapman online

We met when I was 18 and he was 20, before Steve and Deb got together. Stephen Jay Gould was genial and talkative and a tad stout. I remember him at Student Peace Union meetings. This was Antioch College, Yellow Springs, Ohio, 1962. When it came Steve’s turn to speak, he would rise from his chair and deliver an actual address, full of jokes, quite articulate, but long (later he became more concise). His politics was progressive but entirely middle-of-the-road.

We were pals, in a chitchatting sort of way. Between my second and third year, I became depressed and got set to drop out. Steve convinced me to take a formal “leave of absence” rather than cut the umbilical cord to Antioch. I was an erratic, mediocre student. Moreover, I had no clue and could see no sign (and cannot, even looking back) that Steve would become one of the great scientists of our era. He became, of course, a paleontologist and a historian of science. I knew he was geology major, but I didn’t know what he studied or when he studied.

After Antioch there came a gap in our friendship (which quickly became a friendship with Steve and Deb), when fellow student Peter Irons and I began a long relationship and Steve and Deb went off to graduate school, I think, including a year in England where Steve got the amazing gig to write a monthly column in Natural History magazine. That column budded into 300 essays over 25 years, collected into books beginning with Ever Since Darwin and ending with I Have Landed.

Steve obtained his position at Harvard, and he and Deb moved to Cambridge, where Peter and I now lived. There began the years of going over to Steve and Deb’s house for dinner, sitting around the dining table. We talked science, politics, books, history, literature, art. We habitually referred scientific questions to Steve, who was always pleased to expound. Peter and Steve were obsessed with baseball. (I was not.) By now Steve and Deb’s son Jesse was born and later Ethan. Deb, a visual artist, was writing children’s books.

Peter and Steve would go bowling every week or so, at which time they did not discuss science. Both were first-rate, fast writers (Peter was engrossed in the legal scholarship he would become known for). During that decade I worked as a printer, and in the evenings and on weekends I researched a book on the history of coal mining. I was also writing poetry. I was also a political activist. I was also slow. Peter and Steve would chide me, with kindness and humor, but still—“write faster!”

Steve did write faster. Or, more likely, he worked like a bricklayer or an old-style typesetter, steady and persistent. He and his collaborators helped to develop and refine Darwin’s Theory of Evolution in several key ways. One of his contributions (with fellow paleontologist Niles Eldredge) to our understandings of how organisms evolved is that of “punctuated equilibrium,” the notion (supported by the fossil record) that evolution did not chug along at a steady pace like an on-time freight train, but rather: “Lineages change little during most of their history, but events of rapid speciation occasionally punctuate this tranquility.” Evolution, in other words, proceeds in fits and starts. (For a well-introduced selection of Steve’s work, see The Richness of Life: The Essential Stephen Jay Gould edited by Steven Rose.)

The time came when Steve became ill with mesothelioma. Peter and I were horrified, the more so when we heard on TV that the scourge that had befallen our friend was “invariably fatal.” About this we said nothing. Steve broke the ice by talking about cancer, by making cancer jokes. Once, giving him the customary hug hello, I had to conceal my shock at the sensation I was hugging a skeleton draped in loose skin. “Cancer,” Steve said in a jolly tone, “is the best diet.” To refute the news on his alleged fate, that mesothelioma is incurable, with a median mortality of only eight months after discovery, Steve wrote his renowned essay, “The Median Isn’t the Message.” And it wasn’t. He lived.

Years went by. After being married for 20 years, Peter and I got divorced. (We’ve remained good friends.) Later Steve and Deb got divorced. At the time Steve announced that Peter and I were his model of how to be divorced. Okay.

Steve was no paragon of patience. (I couldn’t bear his loss of temper in restaurants.) Deb and I used to talk about Steve and Peter’s extended late adolescence. (No further comment on that.) But Steve was a paragon of productivity. He was a brilliant evolutionary paleontologist and historian of science, and he was a writer.

What did I learn about writing from Steve? I learned that you can compress a big idea into a tight space. I learned that collections of short pieces do sell. I learned that working at a steady rhythm and completing work in manageable units serves the creative enterprise of building a large and meaningful body of work. I noted the benefit of braiding ideas from different worlds. I noted that Steve’s passion for baseball and for music (he sang in the Boston Cecilia chorus) had no digressive effect whatever on his work as a scientist.

This column marks the first birthday of Science Frictions. No, I’m not comparing myself to Steve, but as an essayist who writes on science, I do work under his shadow. I wasn’t sure I could stand the pressure of writing a column a week. (Steve, I thought to myself, only had to write one a month!) I’m not even sure Steve would approve, though I guess he would. I miss him. Steve’s premature death is now 10 years old. It’s still hard to believe he’s no longer in the world. I’ve said goodbye along with the old crowd. Now it’s time to say—publicly—goodbye, old friend. Thank you.

A new Science Frictions essay will be posted on Wednesday, September 5.