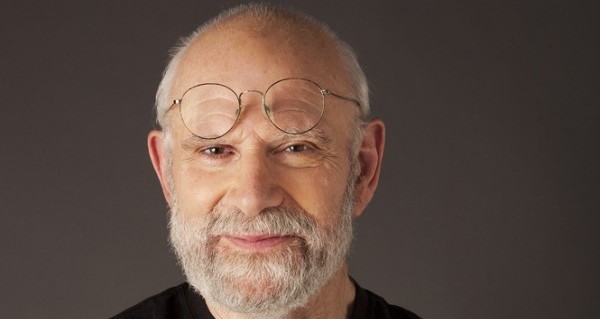

Hallucinations, By Oliver Sacks, Knopf, 352 pp., $26.95

Where do they come from, these odd moments when people know with their senses what their senses cannot know? Why do some such moments grab with divine revelation and others slip away unnoticed? The phenomena themselves are surprisingly varied. They are also normal. You yourself, gentle reader, if you take time to look for strange, unpredictable events at the edge of sight and sound, will find yourself noticing funny little shapes and noises you usually ignore. You may think that the cat was on the couch, but then she wasn’t, or turn to find someone who isn’t there. If you talk with God again and again in prayer, if you expect to hear him answer, you might find that God occasionally speaks to you audibly, in a voice that you can hear outside your head: I will always love you; Start a school; even (I knew this woman) Get off the bus. Then you can wonder, Why aren’t these experiences more common? Why, if God is said to be always talking, do people hear him so rarely with their ears?

Hallucinations is a compendium of causation, a neurological bestiary: sensory deprivation, migraines, epilepsy, delirium, drugs, visions on the edge of sleep, and more. Sacks makes it clear that many of these unusual moments do have specific, organic causes, like Charles Bonnet syndrome, in which deteriorating eyes can see what is not present, sometimes conjuring up fantastic visions. But he is just as clear that hallucinations of all sorts occur among those with no physiological lesions (he leaves psychotic causation entirely to the side, as an animal of a different species altogether). And he is clear that they are important. Hallucinations play a role in every culture we know, although they have lost much of their meaning in our own, so people are afraid to talk about them lest they seem crazy. Sacks’s remarkable achievement is to normalize the strangeness of hallucinations by reveling in their creativity. He wants us to know that even at our most ordinary, we are, as someone once remarked, Goethe in our dreams.

Certainly the stories are riveting. Here is a postencephalitic patient:

Martha N. … would “sew” with hallucinatory needles and thread. “See what a lovely coverlet I have stitched for you today!” she said on one occasion. “See the pretty dragons, the unicorn in his paddock.” She traced their invisible outline in the air. “Here, take it,” she said, and placed the ghostly thing in my hands.

Or here is a woman with Charles Bonnet syndrome:

As we drove away from the beauty parlor, I saw what looked like a teenage boy on the front hood of our car, leaning on his arms with his feet up in the air. He stayed there for about five minutes. Even when we turned he stayed on the hood of the car. As we pulled into the restaurant parking lot, he ascended into the air, up against the building, and stayed there until I got out of the car.

When most of us listen to other people talk, we make them more ordinary than they are because it is so risky to imagine them otherwise. Sacks permits us to attend differently. This does have its dangers. I read the book on a flight from India, hours off my natural time, and when I stretched back to sleep, I had the most vivid dream of walking in a gray-green field, talking to a friend, with a dark orange Plasticine slab attached to my leg that nobody else could see. Listening differently teaches us that our senses stretch at the edges, and the stretch marks can change who we become.

That happened to Sacks. In the 1960s he experimented with drugs—not surprising, given the man and the era. When he began to treat people with migraines, he was taking amphetamines on the weekend, just to see what happened. He spent those days in an intense high of vivid images and thoughts. One weekend he took out Edward Liveing’s On Megrim, Sick-Headache, and Some Allied Disorders, a 19th-century book on migraines, looking for an account of the range of symptoms he heard in his office but found missing from scientific articles.

As the amphetamine effect took hold of me, stimulating my emotions and imagination, Liveing’s book seemed to increase in intensity and depth and beauty. I wanted nothing but to enter Liveing’s mind and imbibe the atmosphere of the time in which he had worked. In a sort of catatonic concentration so intense that in ten hours I scarcely moved a muscle or wet my lips, I read steadily through the five hundred pages of Megrim.

He loved the book, with its detailed observation and its humanity. He wanted more. As he was casting around in his mind for someone who could write more that he could read, a very loud internal voice told him (“you silly bugger”) that it was he. He began to write his own book, found it gave him joy, and never took amphetamines again.

Hallucinations teach us that these odd moments of sensation are an extreme point of a continuum along which what we imagine becomes more real, more possible than the mundane, and that the continuum has power. The terror of horrible imaginings can nearly destroy us, but good moments can change us for the better.

At the end of his book, Sacks turns to the sense of presence. This is a specific phenomenological experience detectable in a brain scanner: a clear awareness that someone is sitting there, right there, even though you cannot see him or her. Perhaps this uncanny awareness, Sacks suggests, evolved over time from a constant watchfulness for predators and potential threats. But see what it makes possible, he suggests. For those willing to trust in the benevolence of the unseen, the presence becomes God. It is the point on which he ends his book.