Man of Faith—and Doubt

Hugh Nissenson should have been better known for his spare historical novels

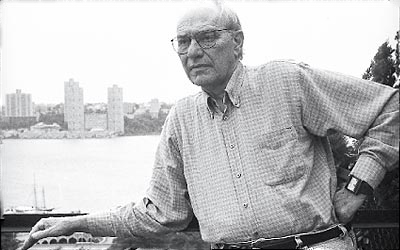

On December 13, the novelist Hugh Nissenson died at the age of 80. He was a great writer, less well-known than he should have been, and a longtime friend.

His best-known novel, The Tree of Life, was nominated for both the National Book Award and PEN/Faulkner Award in 1986. Rare among contemporary American novelists (with the notable exception of Marilynne Robinson), Nissenson always took religion, and the struggle between belief and doubt, seriously. His works are there for anyone who has wrestled with belief, and puzzled over our place in the universe—and who among us has not?

The Tree of Life blends mystical yearning with the bloody fight for daily survival. Set on the seemingly godforsaken Ohio frontier of 1812, it is presented as the terse, blunt “personal journal” of a former minister who has lost his faith. His spiritual wrestling co-exists with his physical struggles, so that his inner wilderness is made visible in an unforgiving landscape.

Although the setting was a departure for Nissenson—in his previous books and stories, he had focused mostly on Jewish characters in Israel and America—the theme of faith and doubt runs throughout his work.

Nissenson also traveled the spiritual territory of other American religious milieus and historical eras, always with a distinctly unsentimental view of epochs that are too easily sentimentalized. Hence, My Own Ground (1976) gives us a seamy Jewish Lower East Side inhabited by holy men as well as pimps and whores. And his last novel, The Pilgrim (2011) featured unflinching descriptions of the putrid sights and smells of the 1620s sea voyage from England to America, as well as of the atrocities Americans both new and native committed upon each other.

Because we are so used to nostalgic historical narratives, shorthand descriptions of these settings can make his novels seem easy to dismiss. But Nissenson’s attention to historical detail was meticulous; he employed a spare, documentary-like style to convey each novel’s particular time and place. Compare him to Graham Greene, whose great subject was also religious faith and doubt.

Earlier in his career, Nissenson wrote extensively about Israel. He covered the 1961 Eichmann trial for Commentary, and published Notes from the Frontier, a book on life in an Israeli kibbutz (1968). He even tackled science fiction (The Song of the Earth, 2001). He also exhibited as an artist (paintings and woodcuts produced for, and reproduced in, two of his novels).

But it was that early writing, focusing on Jewish history and Jewish faith and doubt that led to our friendship. And I cannot talk about Hugh’s work without explaining how I first met him.

Our friendship began with an unexpectedly dramatic flourish, when on the morning of March 9, 1977, I sat in my office at the B’nai B’rith Building in Washington, D.C., and composed a fan letter requesting an interview for a profile in the organization’s magazine, The National Jewish Monthly, where at 24 I was the assistant editor. The news hook was the recent publication of My Own Ground.

Within a couple of hours of my putting that letter in the outgoing mail box, an armed band of Hanafi Muslims (a Black Muslim splinter group) entered and seized the building by force, holding more than 100 of us hostage for 39 hours. Throughout that time, the group’s leader, Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, harangued us with endless anti-Jewish rants, wielding a machete while threatening to cut off our heads. A particularly chilling refrain was that nobody promised us tomorrow; whatever God we prayed to, he added, we should address.

Christians as well as Jews, blacks, and whites were all among those held hostage. Several rabbis who worked at B’nai B’rith were among us. It wasn’t until after we were freed that we discovered that the most significant prayers appeared to have come from the Koran, as conveyed by Ambassadors Ashraf Ghorbal of Egypt, Ardeshir Zahedi of Iran, and Sahabzada Yaqub-Khan of Pakistan, who had agreed to meet with Khaalis. Was it the power of prayer or the power of negotiation that saved us? What did faith or doubt have to do with it? And what meaning was I, or the family and friends I might be leaving behind, to derive from an all-too-short life in extreme danger of being truncated by terror?

However it happened, despite some severe injuries to a few among us, everyone at the B’nai B’rith Building got out alive.

By the time I returned to my office a few days later, my thoughts were still switching back and forth endlessly between the what-happened and the what-might-have-been, even as I picked through the rubble of the overturned desks and cabinets of what had been my office.

Then I came across the letter I had written to Hugh Nissenson. The neatly typed envelope was crumpled and scuffed, the address—West End Avenue, in Manhattan—smudged and splotched. It looked a little like I felt, outwardly worn, even bruised. But when I unsealed the envelope, the letter itself, though wrinkled and creased, was intact.

I wrote a new cover letter to explain what had happened to the original letter. The siege had been the number one news story in the country, so it was not necessary to dwell on details beyond my having been among the hostages and my still wanting to interview him. I carefully wrapped this new letter around the old and placed the envelope in the outgoing mail bin again. Despite my attempt to seem nonchalant, the letter’s subtext was clear: “I’m so lucky to be alive! You can’t possibly say no!”

And he didn’t. Two days later, I picked up the office phone and heard him say, of course, yes! What I didn’t realize was that Hugh’s generosity and warmth were such that he would have said yes anyway.

I discovered at my first meeting with Hugh—in the book-lined penthouse apartment on West End Avenue that he shared with his wife, Marilyn, their two daughters, and a succession of large dogs—that the writer whose voice in print was terse and spare was in person an effusive raconteur whose conversation spilled out nonstop. He saved his editing for the endlessly marked-up, obsessively sweated-over pages that became his nine published books.

Those books, each in its way, turn repeatedly to faith, doubt, and the starkness of the universe. Hugh’s achievement was as a writer who described himself as simultaneously a religious seeker and an atheist. In him, believer and skeptic warred. And his art endures.