Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, by Jan Swafford, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1,077 pp., $40

Ludwig van Beethoven had been dead for only two decades when Alexander Wheelock Thayer first sailed to Europe, in 1849, to separate Beethovenian fact from fiction. The Massachusetts-born, Harvard-educated Thayer, irked by earlier Beethoven biographies, especially Anton Schindler’s Beethoven as I Knew Him—a fog of fact and fiction that helped nurture the Romantic image of Beethoven—decided to put the record straight. It took him half a century and the rest of his life.

“[M]y sole point of view is the truth,” Thayer famously insisted. His work (five volumes’ worth, the last two published posthumously) remains a standard, but like all Beethoven biographies, it is also very much of its era. Its scrupulosity suited Victorian aspirations; its obsessive industry echoed the country he left behind, a hoard of documents and data accumulated with the voracious, single-minded zeal of a Gilded Age collector. It anticipated (and, as an encyclopedic trove of Beethoveniana, facilitated) a perennial parade of Beethoven biographies, every generation reclaiming the man and the legend for itself.

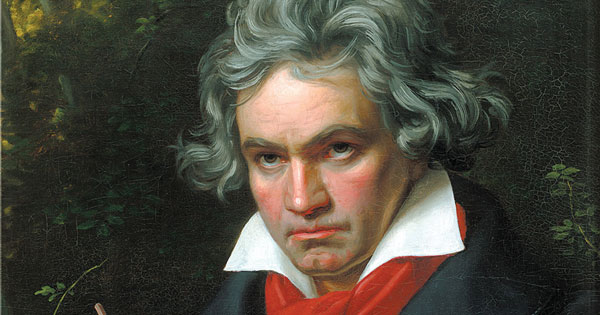

In the introduction to his sweeping, fluent Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Jan Swafford cites Thayer as a guiding spirit, his “sole point of view” as a model. Swafford’s pledge of allegiance to Thayer’s objectivity feels appropriate for a second gilded age, but as his title might indicate, he is also going to proclaim Beethoven a tragic hero, fiercely flawed but still laudable. Maybe it is characteristic of our own era that the possibility of such stature needs underlining; Swafford and Thayer are equally devoted, but Swafford is likelier to empathetically explain his subject’s behavior than simply recount it, likelier to subtly reassure the reader that, two centuries later, Beethoven is still deserving of this much attention and admiration.

How does a biographer clear away the myth while maintaining the mythical status? With Thayer, it was the sheer, all-consuming extent of his research, his diligence, his vocation: such effort was evidence of Beethoven’s worthiness. For Swafford, it is the music, ever affirming and reaffirming Beethoven as (to use one of Swafford’s favorite descriptors) a singular figure.

That it was Beethoven, a commoner, a family-trade musician from a German backwater (however cultured), who became one of the era’s representative figures is even more remarkable given the era’s ferment. One of the book’s strengths is Swafford’s extensive and lucid scene-setting of events in 17th- and early-18th-century Europe. There is the Bonn of Beethoven’s upbringing, an Enlightenment oasis nourished by equal parts imperial indulgence and indifference. There is Vienna, crossroads of imperial power and conspicuous consumption, Beethoven’s home for most of his life, a city that adopted the composer as one of its own even as he regarded it with perpetual contempt. There are the twists and turns of politics unfolding all around Beethoven after his move to Vienna—the decline of the Hapsburg empire, the rise and fall of Napoleon (one of the few of Beethoven’s contemporaries to match his celebrity, then and now), the hopeful advance and disillusioning suppression of liberal political ideals. At every point, we are aware of what is going on in Beethoven’s world, its distance or proximity—practical, financial, psychological—to the composer and his work.

The world was often kept at bay. Early on, Beethoven cultivated a deliberate obliviousness, a retreat into his own imagination, what one female friend dubbed his raptus. Here, away from demands of family, anxieties over money, impositions of wealthy patrons, and the longing for love (all of which Swafford charts in judicious and ultimately distressing detail), Beethoven’s music emerged, in flights of keyboard improvisation, or on long walks in the Viennese suburbs.

It is in describing the music that Swafford, a composer himself, is most expansive and opinionated. The descriptions are poetic, practical, conjectural. They are also the main vehicle for communicating the composer’s exceptionality and, for Swafford, his courage: Beethoven, with determined lucidity, conjuring a realm of mastery even in the face of a messy, painful everyday life.

To an extent unmatched by those of any other composer, Beethoven biographies have tended toward teleology, every piece, every prospect interpreted as either a step or a detour on the way to the monumental figure of popular imagination. Swafford almost can’t help but honor this tradition: Beethoven’s early music, for instance, is divided into moments of conventionality and prophecy, rather than, say, proficiency and provocation. But with those works that he regards as true watersheds—the Third Symphony, the Razumovsky quartets, the Missa solemnis, the Ninth Swafford is a meticulously alert guide. His chapter-length exploration of the Third Symphony, the Eroica, is a tour de force, a reverse-engineered account of compositional technique and audacity that, in its reconstruction of Beethoven’s possible note-by-note decision making, his linking of short, powerful, restated motives into colossal paragraphs, makes as convincing a case for the composer’s transformational preeminence as any exhortative manifesto.

There is, perhaps, something of Beethoven’s motivic saturation in Swafford’s writing itself. The book is idiosyncratically repetitive. Passing characters return accompanied by the same descriptions, as do anecdotes and quotations. Some of it feels oddly but appropriately formal, like the rhythmic fill of Homeric epithets (Emanuel Schikaneder, for instance, operatic impresario to Mozart and Beethoven, is almost always introduced with the fact that he topped the Theater an der Wien with a statue of himself). Some of it is effectively thematic; a lesson from Beethoven’s mother—“Without suffering there is no struggle, without struggle no victory, without victory no crown”—appears like a refrain.

There is even one particular rhetorical tic that hints at the source of Beethoven’s continuing repute. On the Eroica: “Call the symphony’s opening theme ‘the Hero.’ ” On the quality of the slow movement of the op. 59, no. 3 string quartet: “[C]all it Jewish soulfulness, or a lament of some imaginary tribe.” On the opening of the Fourth Symphony: “Call it a nocturnal scene as prelude to a romantic-comic opera.” On one of the composer’s most infamous efforts: “Call Wellington’s Victory the ultimate parody and nadir of Beethoven’s heroic style.” Swafford’s construction, somewhere between a trial balloon and a command, echoes, in a way, Beethoven’s habit of imbuing his music with overwhelming narrative force while refusing to reveal any narrative specificity. Call it imperative suggestion.

There is even one particular rhetorical tic that hints at the source of Beethoven’s continuing repute. On the Eroica: “Call the symphony’s opening theme ‘the Hero.’ ” On the quality of the slow movement of the op. 59, no. 3 string quartet: “[C]all it Jewish soulfulness, or a lament of some imaginary tribe.” On the opening of the Fourth Symphony: “Call it a nocturnal scene as prelude to a romantic-comic opera.” On one of the composer’s most infamous efforts: “Call Wellington’s Victory the ultimate parody and nadir of Beethoven’s heroic style.” Swafford’s construction, somewhere between a trial balloon and a command, echoes, in a way, Beethoven’s habit of imbuing his music with overwhelming narrative force while refusing to reveal any narrative specificity. Call it imperative suggestion.

The gap between experience and explanation pervades our perception of Beethoven’s life and work. Swafford does right by his subject, presenting Beethoven and his music with all their sometimes cataclysmic contradictions intact: traditional and revolutionary, awful and generous, high-minded and grubby, violent and kind. The contradictions were and are never resolved. That elusiveness, not least the contrast between the sublimity of the music and the ill-behavior of its creator, invited the Romantic mythmaking that still colors our impression of Beethoven, and of art and artists in general. But it also makes him perpetually compelling, ever revealing additional facets.

Swafford relates Anselm Hüttenbrenner’s account of Beethoven on his deathbed, shaking his fist at a clap of thunder before expiring. “[It] is a death from myth,” Swafford admits, but “[i]t may as well have happened that way as any other.” It is the possibility held out by Beethoven’s life: that, even with feet of clay, one might still plausibly soar to the empyrean.