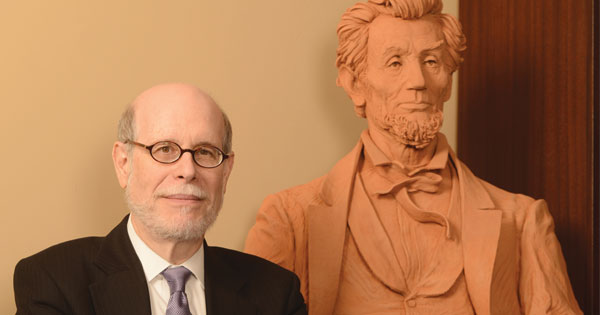

Harold Holzer is a leading Lincoln scholar and editor, a historian of the political culture of the Civil War era, and a Metropolitan Museum of Art senior vice president. He served as script consultant for Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln. Holzer’s own Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion was published in October. We asked him to pose five questions, relevant to today, about our 16th president and his skills in manipulating the press.

1. “Must I shoot a simple-minded soldier boy who deserts, while I must not touch a hair of a wiley [sic] agitator who induces him to desert?” So Abraham Lincoln wrote in June 1863 to defend his latest wartime crackdowns against free speech and liberty of the press. As America launches what the Obama administration warns will be an even longer conflict against ISIS, would even the most audacious domestic dissent, no matter how threatening to the homeland, justify the persecution of journalists and editors who object to the conflict?

2. In Lincoln’s day, journalists served concurrently as politicians. Henry Raymond, editor of The New York Times, ran for Congress and chaired the Republican National Committee during Lincoln’s 1864 re-election campaign. Yet law and tradition prohibit such crossover careers today. Honestly, why shouldn’t former politicians (and current TV commentators) such as Mike Huckabee (Fox) and Newt Gingrich (CNN) be allowed to try electoral comebacks without giving up their broadcast slots? Why this modern-day dividing line between politics and the press when no one doubts the respective political orientation of, say, Fox or MSNBC?

3. Abraham Lincoln: relevant or relic? Arguably, Lincoln was a PR genius—he understood that “he who molds public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions.” But if he lived today, could this oversized, bearded, homely, squawk-voiced politician mold public sentiment in the unrelenting glare of the 24-hour television and Internet news cycle?

4. What is the best model for presidential leadership? During the Civil War, Lincoln insisted that “events have controlled me” rather than the other way around. Some argue that this confession reveals Lincoln as an insincere emancipator who moved against slavery only because he could no longer resist the forces of freedom. Others insist Lincoln was an astonishingly sophisticated pol who wrote the book on leading from behind—letting the press, for example, push him toward policies he already intended to pursue. Which was the real Lincoln? Leader or follower? And in what ways should modern presidents try to be Lincolns?

5. Lincoln read newspapers voraciously from his boyhood on—seldom allowing an error or criticism to go unanswered once he entered politics. He wrote anonymous editorials, drafted articles, befriended and berated journalists, and continued devouring so many papers that his wife, Mary, once chased a newsboy from her front porch because it was littered with so many subscriptions. Yet as president, Lincoln stopped reading the press altogether and neglected even the press digests his aides prepared for him—saying he understood public opinion better than the journalists anyway. Is a president better off obsessing about press coverage—or pretending it doesn’t exist?