White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America by Nancy Isenberg; Viking, 480 pp., $28

Some years ago, in a book I wrote about a Pentecostal congregation of snake handlers in the mountains of Appalachia, I observed that poor southern whites were “the only ethnic group in America not permitted to have a history.” Since then, whenever I’ve repeated this line in public, someone from the audience inevitably asks, often with some hostility, “What do you mean by that?” My answer has always been the same: “The fact that you would ask me that question is what I mean by that.” But thanks to Nancy Isenberg, a professor of history at Louisiana State University, we now have a history of poor southern whites to place alongside those of African Americans and other brutalized or vilified people who came to America against their will.

Her book bears an imposing title: White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America. Because Isenberg dares to question what she calls “the limits of conventional wisdom,” White Trash is certain to be controversial. No debate, however, can minimize the rigor of Isenberg’s research, the clarity of her prose, or her courage in exploring this fraught subject. Hers is a book that should forever change the way we think and talk about class, which Isenberg suggests is the rotting stage upon which American democracy will either stand or fall.

Other seminal works on impoverished southern whites, such as Wayne Flynt’s Poor but Proud: Alabama’s Poor Whites and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, are rooted in the particular times they portray—Flynt’s the antebellum South, Agee’s the Great Depression. David Hackett Fischer’s brilliant Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America takes on the broader avenues and scope of Anglo migration to the New World but doesn’t fully account for it or discuss its consequences.

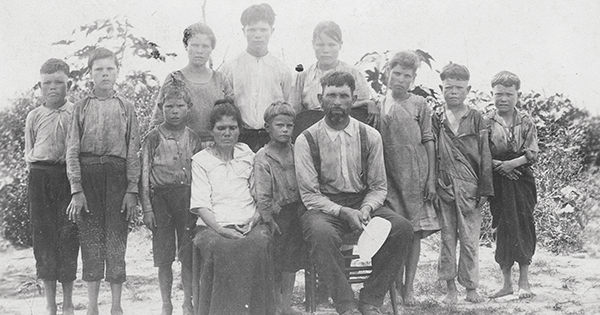

Isenberg’s focus is more comprehensive, starting at the very beginning and shattering the illusion of America as a “shining city on a hill.” The upper-class Englishmen who migrated here in search of a new Eden did so on the backs of indentured servants, convicts, and women, white and black alike, whom they bred like livestock. Most early settlers, rather than seeking religious freedom or commercial gain, were fleeing England’s streets and prisons. Isenberg writes that they were what 16th-century noblemen such as Richard Hakluyt (the younger) called “waste people,” who ought to be thrown out of or lured away from their home country even if it meant dying or barely scraping by in an inhospitable wilderness an ocean away.

The hallowed Founding Fathers brought with them the rigid class distinctions of the Old World. Thomas Jefferson, for example, simply offered a softer version of inequality, one that ascribed differences in wealth and physical comeliness to the science of husbandry. If landowners would only choose the wisest methods of cultivating their crops and breeding their animals, he thought, they would soon climb the ladder of gentility.

The poor were largely left out of Jefferson’s equation, Isenberg argues, with the exception of his failed attempt to include a provision in the Virginia constitution that would have granted white, male, landless peasants 50 acres and the vote. In another of his efforts to balance the scales, he put forward a plan to “rake” promising young scholars from the “rubbish” of the poor and educate them in life’s finer points. Isenberg wonders whether Jefferson’s word choice was simply carelessness or a sign of his less-than-perfect philanthropy. Jefferson’s contemporary Benjamin Franklin entertained similar notions about ennobling the poor, although, as Isenberg says, he felt “deep contempt” for them. Franklin’s prescription for addressing poverty consisted of encouraging vigorous migration of the poor into the western frontier lands and energetic reproduction by this “happy mediocrity.” In an aside, Isenberg notes that “bastards were a Franklin family tradition,” since Franklin’s son William was one, and William fathered another himself.

The gradual expulsion of poor Anglo-Irish and Anglo-Saxon immigrants from the respectable Quaker cities of the Atlantic Seaboard produced yet another kind of refuse: a sludge composed of “cracked brained” squatters who fled into the mountains of Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia and bred their numerous, cadaverous children on land that was not, and would likely never be, their own.

Isenberg outlines the template by which we came to judge poor southern whites as obscene, boastful, lazy, and violent—characterizations that persist in popular American culture, from the halls of Congress to the pulpits of churches to the classrooms of our universities. Sure, loud-mouthed, ill-mannered Andrew Jackson, the ultimate cracker’s cracker, rose to the presidency in 1829, but not much else had changed in the 200 years since vagrants and beggars swept from the streets of London first began arriving in the New World—nothing except the names by which they would be called.

Isenberg notes that the particularly insulting term “poor white trash” first entered into common usage in the years leading up to the Civil War, most notably during Andrew Jackson’s funeral procession in 1845, when poor whites shoved poor blacks out of the way to get a better look at their dead hero. The term then began to be used as though it designated a separate, degenerate “race” lower than that of African slaves—a cruel paradox since poor whites would end up doing most of the fighting and dying during the looming civil conflict. The upper-class planters and slaveholders, meanwhile, cheated death as though life itself were just another unquestionable privilege of wealth.

One of the surprising revelations in Isenberg’s book is that abolitionist writers of the period frequently directed their attacks not against wealthy plantation owners but against poor southern whites, who often worked alongside the slaves and lived under similar conditions—an observation sure to provoke the ire of some readers but consistent with the results of Isenberg’s research.

White Trash’s dogged adherence to fact elevates it above the level of melodrama. It is a fact, for instance, that American eugenicists advocated the sterilization or castration of southern whites, whose only crime was poverty. It is a fact that many of the southern demagogues who whipped up racial violence in the 20th century came from the wealthy political class and were not the poor rednecks they pretended to be. It is a fact that the opponents of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal policies were primarily wealthy southern senators feeding at the corporate trough.

White Trash, more than a simple history of the southern poor, is a beautifully cadenced argument against the rape of the American underclass, and Isenberg’s use of cinema and literature to illustrate her points is admirable. Along with the violent film Deliverance and several movies directed by Elia Kazan, Isenberg discusses books by William Faulkner, James Agee, Erskine Caldwell, and Harper Lee. To that familiar list she adds Dorothy Allison’s heart-rending novel Bastard Out of Carolina and Carolyn Chute’s The Beans of Egypt, Maine, which draws an unforgettable portrait of life among the white “waste people” in a Maine trailer park. But Isenberg’s own words are often as direct and memorable as those of the writers she names: “When it came to common impressions of the despised lower class,” she writes, “the New World was not new at all.”

The sad truth is that genuinely poor southern whites are a people without a country, or at least the kind of country that puts their interests on an equal footing with those of the ruling class. The rich preachers in their megachurches like to remind us that Jesus said the poor are always with us, but they forget to add that he also said, “As you do unto the least of these, you do unto me.”