Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast by Megan Marshall; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 365 pp., $30

Megan Marshall’s Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast is actually two books bound in the same cover. Both are interesting, but one is much better than the other. The first “book” is a compelling new biography of Bishop, who is now widely considered the most important American poet of the mid-20th century. Using a wealth of new material, including the poet’s letters to her lovers and psychoanalyst, Marshall has crafted the most intimate and accurate biography yet available. Anyone interested in Bishop’s life and work will need to read this moving and often revelatory new account.

The second “book” consists of seven short memoirs by Marshall that surround each chapter of the formal biography. These sections purport to provide personal perspective on Bishop—Marshall was once her student at Harvard—but are essentially sketches of the biographer’s own life. Accounting for one-sixth of the book’s total length, these reminiscences often have little to do with Bishop and weigh down the central narrative. Marshall’s life might make an interesting tale, but her treatment here feels blunt and inchoate. The author clearly intends an experiment in biography—a mixture of objective narrative and subjective commentary. It does not succeed.

The purely biographical sections redeem the project, however. Marshall, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 2014 for her life of the transcendentalist literary critic and journalist Margaret Fuller, tells Bishop’s story with admirable clarity and economy. Most biographers are better at gathering material than presenting it; their narratives often bog down in a morass of research notes. Marshall has a novelistic gift for crafting a narrative sensitive to both the inner and outer realities that shape a life. This double perspective is necessary in understanding Bishop’s contradictory existence, so outwardly quiet and inwardly tormented.

Bishop was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1911, the only child of an oddly matched couple—a wealthy American father and a Canadian mother raised in rural poverty. Almost at once, tragedy struck, when Bishop’s father died before her first birthday. Three years later, her mother was institutionalized after a suicide attempt. For a few happy years, young Elizabeth was raised by her Canadian grandparents in Nova Scotia. Then her American grandparents brought her back to their prosperous but emotionally icy home in Worcester.

The abrupt relocation nearly killed the delicate and already traumatized child, who developed asthma and eczema. Eventually Elizabeth was moved again while in their care to recuperate with her aunt, whose husband may have sexually molested her. Remembering her early childhood in a poem, she observed, “Time to plant tears, says the almanac.”

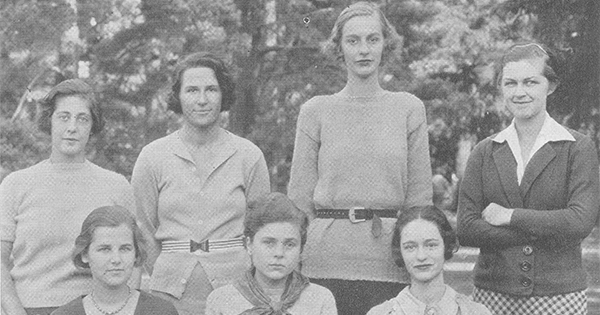

Bishop was sent to boarding school at 15 and then to Vassar. Her romantic attachments were always to women. By graduation her mother and grandparents were dead, each leaving her a small legacy, making her independent but homeless. The rest of her life became a restless search—invariably unsuccessful—for the stable home and secure love her childhood had denied her.

Not surprisingly, travel and dislocation emerged as recurring themes in her poetry. The novelty and wonder of new places, however, were always tinged by sadness and doubt. In “Questions of Travel” she concludes (using one of her signature points of style, emphatic italics):

Continent, city, country, society:

the choice is never wide and never free.

And here, or there … No. Should we have stayed at home,

wherever that may be?

The surface of Bishop’s life was a genteel mess. Supported by her trust fund, she drifted from place to place, suffering through tangled relationships, alcoholic breakdowns, and frequent illnesses. “I was made at right angles to the world,” she wrote. Her love affairs, all begun when she was drunk, inevitably ended badly. The central relationship of Bishop’s life, with Brazilian landscape architect Lota de Macedo Soares, climaxed in her partner’s suicide.

At the time of Lota’s death, Bishop was in the process of returning to the United States from Brazil. Her inheritance had dwindled. At the age of 56, she had to seek regular employment for the first time—accepting a teaching position first at the University of Washington and then at Harvard. Her final lover, the sensible and steady Alice Methfessel, hoped—like all her predecessors—to curb Bishop’s drinking and depression. She failed. In 1979, worn out by alcohol, tobacco, and a small mountain of prescription drugs, Bishop died at 68.

Underneath the terrible disorder and dysfunction, however, was the poet’s intense but preternaturally patient focus on writing—the one part of her existence she could perfect and protect. Bishop never wrote much. She published only about a hundred poems in her lifetime, but they were so fresh and original that she immediately achieved elite recognition. Her first book earned her both a New Yorker contract and the Consultant in Poetry job at the Library of Congress (the position now called U.S. Poet Laureate). Her second book won a Pulitzer and several fellowships. Bishop eventually became the first woman to teach an advanced writing class at Harvard. Her success never surprised her. Although popular recognition came only in her final years, Bishop knew her worth.

Readable and reliable, Marshall’s book is not a scholarly biography. She does not meticulously present all of the facts of each episode in Bishop’s life or often acknowledge the limits of her own interpretations. Instead, she has written a well-paced and well-argued narrative account. Marshall gets the complicated shape of things right, though she might have explored the ambiguity of many moments, especially in Bishop’s traumatic childhood.

There should also have been better coverage of Bishop’s long relationship with The New Yorker and her most important editor there, Howard Moss. Marshall makes no mention of poet Anne Stevenson, who wrote the first book on Bishop in 1966, when few critics took her seriously. This book concentrates disproportionately on the Harvard years and Robert Lowell, a singular friendship but one that has been repeatedly covered elsewhere. She nicely documents Bishop’s relationship with poet-translator Robert Fitzgerald, though she oddly describes this well-built man of just under average stature as “elfin.”

Other and better biographies of Bishop will come. Despite its shortcomings, Marshall’s concise biography provides an accessible and engaging account for the common reader. Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast is the rare sort of book that will expand the audience for contemporary poetry.