The Poetry of Weldon Kees: Vanishing as Presence by John T. Irwin; Johns Hopkins University Press, 120 pp., $32.95

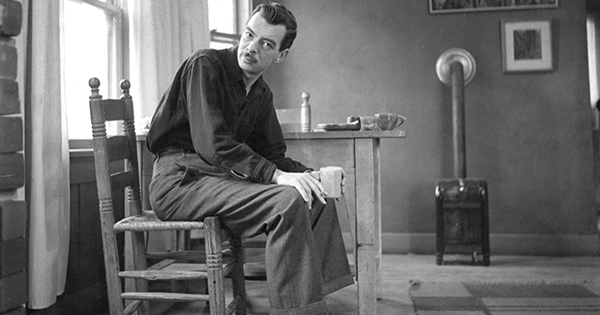

Weldon Kees is the most mysterious figure in modern American poetry. Lean, handsome, and impeccably dressed, he looked like a B-list Hollywood star, the sort who played the nightclub owner in film noir. In photographs, Kees smokes and broods—cool, stylish, and doomed. Born in Nebraska in 1914, he drifted through half a dozen colleges and cities before arriving in New York in 1943. An artistic polymath, he excelled at every medium he attempted—poetry, fiction, painting, jazz, journalism, and film. His poems appeared in The New Yorker. His paintings earned him a one-man show, praised by his fellow abstract expressionists. He wrote for Time, edited newsreels for Paramount, succeeded Clement Greenberg as art critic for The Nation, produced experimental films, wrote songs for a San Francisco cabaret, and coauthored a pioneering book in semiotics. If the career sounds brilliant but unstable, so was the man. As soon as Kees achieved something significant, he became dissatisfied—with his medium, his colleagues, or himself. Only poetry held his attention.

Fame eluded him, and polymathy didn’t pay. “An age of specialization,” Kees observed, found artistic versatility “puzzling or irritating and sometimes suspicious.” A restless bohemian, he didn’t fit into the academic postwar poetry world. Using ingenious forms often invented for a single occasion, his poetry promiscuously mixed high and low culture on equal terms. His lines veered suddenly from sardonic satire to piercing lyricism. Mordantly outspoken, he had no gift for cultivating the mediocrities who filled the ranks of metropolitan cultural life. “Problems of a Journalist” begins,

“I want to get away somewhere and reread Proust,”

Said an editor of Fortune to a man on Time.

But the fire roared and died, the phoenix quacked like a goose.

The poet’s former colleagues at Time surely understood the insult. “I can tell from the way you act you don’t want to be a success,” Truman Capote admonished Kees at a party. “Why, you’re a much better poet than that old Robert Lowell.”

For 15 years, Kees moved on intimate terms among the major figures of American culture. His friends included Hans Hoffman, Edmund Wilson, Willem de Kooning, Mary McCarthy, Romare Bearden, and Pauline Kael. In 1950, Kees moved to San Francisco, where he found the artistic scene “remarkably fluid, open, adventurous.” He experienced a burst of creativity in half a dozen arts, and then his life started falling apart from alcohol, drugs, divorce, and persistent failure. In 1955, Kees disappeared. He almost certainly committed suicide by jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge. He was 41.

After his disappearance, Kees vanished from cultural memory. His poetry, which had been published mostly in limited editions, went out of print. His paintings were given away. His other writings remained uncollected. Critics and anthologists ignored him. Posthumous oblivion is the fate of nearly all authors. What saved Kees was the conviction among a few writers that he was, as his first champion, Donald Justice, asserted, “an important poet, among the three or four best of his generation.”

Over the next half century, a cult of Kees slowly emerged among writers, first in the United States and then abroad. Recognizing his work—still difficult to obtain—became the literary equivalent of a secret Masonic handshake. Although Kees remained invisible to academics, he exerted a powerful influence on young poets. The huge gap in Kees’s reputation between poets and professors came to symbolize the stark differences in literary taste among creative and theoretical thinkers who often coexist uneasily in the same English department.

John T. Irwin, a poet and literary critic who teaches at Johns Hopkins University, has partially closed the gap in a brilliant new study of this neglected author. Most pioneering monographs are cautious in their approach. Irwin’s The Poetry of Weldon Kees: Vanishing as Presence is audacious and provocatively speculative. Declaring Kees “the most interesting poet of his generation,” Irwin frames the author’s life and work against a backdrop of modern literature and philosophy. Concise, clearly argued, and free from critical cant, the book is a model of scholarly writing; it also reminds the reader how revelatory literary criticism can be. For Irwin, the stakes are not merely academic; understanding Kees is literally a matter of life or death.

Irwin begins by carefully examining the circumstances of Kees’s “disappearance.” No one saw the poet jump from the bridge. His car was found (with the keys inside) in the Vista Point lot at the Golden Gate’s north end. Kees left no suicide note, but in his apartment police found his cat, Lonesome, and two books placed conspicuously by the bed—Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Devils and Miguel de Unamuno’s Tragic Sense of Life. Both volumes contain extended considerations of suicide as an act of existential defiance. Kees had mentioned going to Mexico to start a new life. Irwin interprets the poet’s statements as deliberate misinformation to make his disappearance enigmatic. No body was ever found. Irwin speculates that Kees deliberately chose the time of his death to have the tides carry him out to sea. “Kees likely staged his death,” Irwin concludes persuasively, “as his final aesthetic act.”

Building on his daring hypothesis, Irwin places Kees as a significant figure in the existentialist lineage of Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Unamuno, and Camus. The poet’s apocalyptic worldview contains the same theistic-nihilistic dichotomy pondered by Dostoevsky and Unamuno–either belief in God or despair. Although Kees ached from spiritual hunger, he possessed no capacity for religious belief. Lacking both Dostoevsky’s faith and Unamuno’s existential sangfroid, Kees suffered from the intolerable tedium of living in a world robbed of meaning. He shared Camus’ conviction that the “only truly serious philosophical problem” was suicide. As Irwin suggests, the poet’s death reflects Unamuno’s insight that “the self-slayer kills himself because he will not wait for death.”

The book analyzes Kees’s major poems to support the theory of suicide as an intentional aesthetic act, an existential validation of the author’s worldview. Corroborative evidence isn’t hard to find. Death, suicide, drowning, and despair are ubiquitous in the work, though it must be noted that Kees had an eerie genius for making the apocalypse simultaneously terrifying and mordantly amusing.

Irwin’s sensitive readings are consistently illuminating. He is particularly good at uncovering the complex sources that characterize Kees’s urbane and allusive verse. Oddly, however, in his analysis of “A Distance from the Sea,” a poem that stands at the center of his existential argument, Irwin entirely misses the source. In this long dramatic monologue, Kees crafts the voice of an aged apostle who reveals how and why Christ’s miracles were faked. Irwin seems unaware that Kees based the poem on passages from Albert Schweitzer’s The Quest of the Historical Jesus. That source not only clarifies the poem; it also indicates that late in his life, Kees studied a classic of modern Christology, though he never found Dostoevsky’s religious consolation.

Was Kees’s suicide an act of existentialist assertion or simply a surrender to despair? Perhaps it was both. No life is entirely rational, and the great turning points rarely have a single cause. In either event, the strange nature of Kees’s disappearance, deliberate or accidental, imbues his work with mystery and mortal gravity. Like the title image of his poem “A Good Chord on a Bad Piano,” Kees’s life remained “double to the end, / Like all the smashed up baggage of the heart.”