Peggy’s War

A pioneering American journalist traveled the world while fighting her own battles at home

![pegs "As long as we have American boys [at war], I want to write their story for them," said Hull, pictured here with three Army officers during World War II. (From the Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas)](https://theamericanscholar.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/pegs-1024x572.png)

Peggy Hull heard the news of V-E Day on a static-filled radio in the orderly room at a location she described in her dateline only as “A Little Army Camp in the South Seas.” She and “her boys” found it hard to get too excited about the news. Hull had lived alongside the young soldiers for several months, roughing it, as she wrote to a friend, “in a hut in an army camp—sleeping on a canvas cot—running out of doors to a latrine and a shower shed quite a distance away—plowing through dust one day and mud the next.” Some of the soldiers had been at their stations for more than three years, longer than any American forces had been in the European theater. The most they were hoping for was that Germany’s surrender would free up forces to support them. As Hull reminded her American readers, “It is over on that side of the world, but it is not over, over here.”

Yet “over here” was exactly where Hull wanted to be. During World War II, new opportunities opened up for women in the newspaper business as men left to become soldiers or war correspondents. With publishers desperate to fill the vacant positions, women reporters made the leap from the society page to the front page. By 1943, newspaper staffs in smaller American cities were 50 percent female. Some women worked as copy editors and typesetters. Some ran presses. But almost 130 found their way overseas as war correspondents.

At 54, Peggy Hull was determined to be one of them. The first woman accredited as a war correspondent by the U.S. military, she had already reported on four armed conflicts between 1916 and 1932, often traveling alongside the soldiers, and she was eager to get back into the game. As Hull told a reporter for Editor & Publisher shortly after she arrived in the Pacific theater, “I’ll never tire of doing this work, and as long as we have American boys in isolated parts of the world, I want to write their story for them.”

In 1905, 16-year-old Henrietta Goodnough applied for a reporting job at the Junction City Sentinel, a small-town paper in her native Kansas. The editor told her he didn’t need another reporter, but if she didn’t care about the condition of her fingernails and was willing to set type, she had a job. She took it. Two weeks later, she received her first reporting assignment.

Over the next 10 years, she moved from newspaper to newspaper, chasing opportunities and, for a time, following her first husband, a charming journalist with a drinking problem named George Hull, whom she married in 1910 and divorced six years later. She worked at newspapers in small towns and big cities in Colorado, California, Hawaii, Ohio, and Minnesota. Her editor in Minneapolis encouraged her to use a pseudonym, saying he wouldn’t be caught dead putting a name like Henrietta Goodnough Hull at the top of a column in his paper. Together they came up with Peggy Hull—the name she would use for the rest of her life.

She wrote feature stories, human-interest pieces, “little tales” for the children’s section, and accounts of trials, plus shopping columns that were the early-20th-century ancestor of native advertising, a form she fell back on whenever reporting jobs were in short supply. Hull was writing one such shopping column for the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1916 when President Woodrow Wilson mobilized the Ohio National Guard to patrol the Mexico-U.S. border as part of General John “Black Jack” Pershing’s Punitive Expedition against the Mexican revolutionary general Pancho Villa. Hull decided that she wanted to travel with the troops as a reporter.

The transition from shopping columnist to war correspondent was not an obvious one. The managing editor of the Plain Dealer refused to give her the assignment, saying he “wouldn’t be a party to sending a girl to an army camp.” Unable to get financial backing from the newspaper’s editorial department, she announced her intention to work as a freelancer, selling stories to any newspaper that would buy them.

So many reporters requested permission to accompany Pershing’s troops into the field that an overwhelmed War Department was forced to improvise a lottery system. With even reporters from major publications jockeying for permissions, it’s not surprising that a woman freelancer was not allowed to travel to the front. Although Hull didn’t make it into Mexico with Pershing’s army, she managed to become the darling of the troops that guarded the border when she marched with them on a grueling 15-day hike from El Paso, Texas, to Las Cruces, New Mexico.

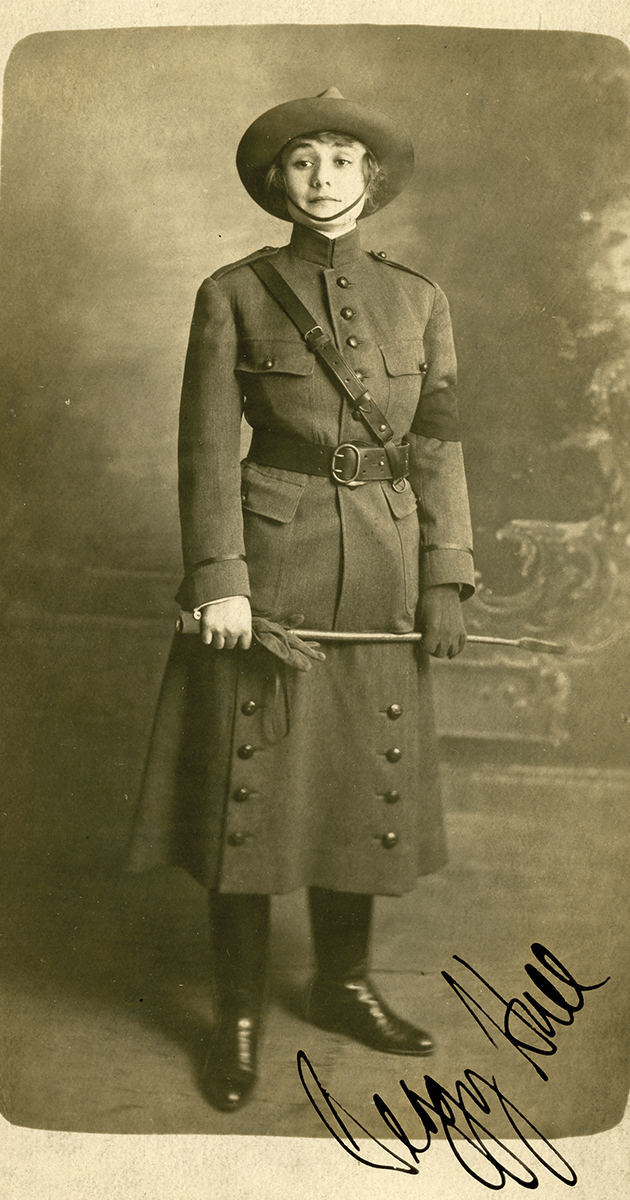

The march turned out to be harder than she expected. The uniform she had designed for herself, based on those worn by the Ohio guard, consisted of a gray wool skirt that reached to midcalf, a tailored flannel tunic, and a campaign hat with a chin-strap, but it did little to protect her from the elements, and her heavy rubber-soled shoes were not as sturdy as the soldiers’ boots. Hull’s feet started to hurt before she reached the El Paso city limits. As the day went on, she lagged farther and farther behind. She wasn’t alone. By the day’s end, a young soldier limped beside her. The next day was even worse. A sandstorm blew up, and Hull reported to her readers:

Units became separated. Minor commands were lost. Water wagons were overturned in the desert, or else lost their way and wandered from the main column. The wind raged and blinded us all with fine white sand. We had no luncheon and no dinner. About one o’clock in the morning after the storm had spent itself, our weary field kitchen staggered into camp and the First Kentucky Field Hospital—I was traveling with them—turned out for food—and such food. Sanded bacon—sanded bread—sanded coffee sweetened with sanded sugar.

She was miserable. She felt as if she “had never had a bath,” and her hair was so bristly that it was hard to sleep on it. But she had convinced the officer in charge of the march to allow her to join it, and she refused to quit. By sheer determination, she lasted until she reached Las Cruces.

Hull’s account of the discomforts of her march with the men was typical of her reporting from the border: sassy, brassy, and humorous. Most of her stories were short, chatty pieces that described her experiences of being near, if not on, the front. The reports gave people back home a reassuring glimpse into the daily lives of the troops. But the headline of Hull’s final story about the Punitive Expedition made it clear that this story would have a different tone: “Pershing’s Ten Thousand Back From Mexico Desert, Silent, Swarthy and Strong.” Her description of the expeditionary force’s return ran on the front page of the El Paso Morning Times on February 6, 1917, and was accompanied by a picture of Hull in the uniform that she had designed for herself.

As a reporter, Hull didn’t have a uniform, so when she accompanied the troops to New Mexico, she designed her own. (From the Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas)

The article is heavy with dust, exhaustion, and the sound of tramping boots. When General Pershing and his aides rode past, she noted that “their faces were seamed and white dust hung heavily on their faded uniforms.” As the dust from their horses’ hooves settled, the infantry marched into view, heralded by “a hundred tiny beams from the barrels of glistening rifles [belonging to the] boys who had walked—over hundreds of miles of dry country—over rocks, hills and almost impassable mountains—all the way there and now—all the way back.” This was not “the triumphal return of a victorious army,” but it was also not the dejected retreat of the defeated. Eleven months in Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa’s elusive band had transformed Pershing’s amateurs into “an efficient, unsentimental, hardened fighting machine.”

A different version of Pershing’s return appeared on page four of the Morning Times. Hull had upstaged the general by meeting him on horseback as he led his troops out of Mexico and into El Paso. The Morning Times ran a photograph of Hull riding next to Pershing on a white horse and holding a giant bouquet, with the caption, “Peggy Rides at Head of Cavalcade of Distinguished United States Army Officers.” Newspapers around the world published the same picture with the caption, “American girl correspondent leads troops out of Mexico with General Pershing.” Black Jack Pershing was not amused.

If the Punitive Expedition failed to capture Pancho Villa, it did accomplish something more important. It served as a training ground for America’s entry into the war then raging in Europe. It also seasoned self-styled “girl reporter” Peggy Hull. Denied permission to cross the border into Mexico and report on the activities of Pershing’s troops in the field, she developed what would become her trademark style of reporting: “little stories” about the daily life of an army at war, almost two decades before Ernie Pyle became famous for a similar approach. She also made contacts that would be important for the rest of her career—members of the press corps such as Floyd Gibbons and Webb Miller, who would become influential correspondents, lieutenants who would become colonels, and colonels who would become generals. Many of them would help Hull overcome bureaucratic hurdles in the future.

The Ohio National Guard returned to Cleveland at the end of the Punitive Expedition, but Hull stayed in El Paso, writing for the Morning Times. When the United States entered World War I two months later, in April 1917, Hull hinted to her El Paso readers that she was up to something: “I can’t tell you now just what I’m going to do, but it is a great big secret and oh goodness, but you’ll be surprised.” The first person she surprised with her plans was James Black, the managing editor of the paper. When Hull asked him to send her to France as its war correspondent, his immediate response was that her proposal was “perfectly ridiculous.”

She wore him down. By the time she left Black’s office that day, she had received a “roving commission” to write human-interest stories about the war and a commitment that the paper would pay most of her expenses—if she could get the necessary passport and visas. That was a big if, so big that Black may have thought it was a way to say no without saying no. But as so many others would do over the years, Black underestimated Hull’s persistence. With her passport and the necessary British and French visas in hand, she arrived in Liverpool four days behind Pershing, who was now the commander of the new American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.). She stayed in Britain just long enough to have a tailor make a new uniform for her. Even with the tailoring delay, Hull reached Paris in time to see the first American troops march into the city on July 4, 1917.

In the summer of 1917, American soldiers were not yet at the front. Instead, they were receiving training in trench warfare and artillery in camps in the safe regions of France, a situation ideal for producing the human-interest stories that Hull specialized in. While the accredited male correspondents waited in the field headquarters in the town of Neufchâteau for American soldiers to move forward to the Western Front, Hull reported on news wherever she found it, no matter how small.

She used her relationship with several high-ranking officers whom she had met at the Mexican border, including General Pershing himself (who had forgiven her for upstaging him at Las Cruces the year before), to wrangle permission to stay at the American training camp in the French town of Le Valdahon, even though she did not have a pass that allowed her access to the camp. For nearly six weeks, she enjoyed the hospitality of the A.E.F. and the camp’s commander, Brigadier General Peyton C. March. A young lieutenant escorted her to the area where men trained to use trench mortars, happily answering her questions. A French aviator took her up in a plane that “looked more like a mosquito than an airplane” so that she could observe artillery fire from the air, before giving her the heart-stopping experience of spinning back down toward the earth. She ate breakfast in the mess hall with young soldiers, spent chilly afternoons in the rain with them, and rode along to the train stations from which they departed for the front.

Soon Hull’s stories about her experiences, published under the title “How Peggy Got to Paris,” were appearing not only in the Morning Times but also in the Chicago Tribune and the Tribune’s Army Edition, a four-page tabloid for American soldiers in France. The stories were chatty and amusing, with a byline simply of “Peggy” and an unnamed American training camp as the dateline. Soon other American papers were picking up her stories from the Tribune. The accredited male war correspondents, who believed they had written everything there was to write about the troops in the training camps and were waiting impatiently for a chance to report “real” news about the war, started getting cables from their editors asking why Peggy, whoever she was, was turning in stories they hadn’t found.

These correspondents knew that no woman had received credentials as a war correspondent with the A.E.F., although some had applied. They were frustrated by Pershing’s unwillingness to talk to them and the restrictions imposed on them by Major Frederick Palmer, a former war correspondent who headed the A.E.F. press division. When Hull informed the Tribune’s readers that she was a guest of the training camp’s commanding general thanks to special permission from Pershing himself, the complaints began to roll in.

The recipient of those complaints, Major Palmer, was if anything more upset than the correspondents over Hull’s unofficial privileges—and that she had bypassed both his office and the military censors. Palmer immediately sent a long, bureaucratic memo to Pershing, demanding that matters be rectified. Pershing had bigger—and literal—battles to fight. Unaccredited, and without a powerful supporter, Hull was forced to head home.

Back in El Paso, Hull couldn’t let go of the idea of returning to Paris as an accredited war correspondent. In the summer of 1918, she traveled to Washington, D.C., prepared to make it happen. Once in Washington, news of an exciting new military expedition wiped out all thoughts of Paris.

In early July, President Wilson approved sending a small force of American soldiers to Siberia as part of an Allied initiative to support White Russians fighting the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. From a military perspective, the Siberian intervention was a sideshow within a sideshow. From a hungry journalist’s perspective, it was a fresh story without a crowd of competing reporters already in place. Two familiar obstacles stood in Hull’s way: she needed a newspaper to pay her expenses to Siberia, and she needed approval from the War Department.

The managing editor of the Tribune’s Army Edition had offered her work before she left Paris, but that wouldn’t help her get to Siberia. In her search for a sponsor, Hull contacted every editor she had ever known. Then she wrote to editors she had no history with. She received 50 refusals before she got a positive response from S. T. Hughes, editor of Newspaper Enterprise Association, a syndicate whose primary outlet was the Cleveland Press.

Despite her troubles with the press division in France, the second hurdle proved to be relatively easy, thanks to her friend, General March, who was back from Paris and now the army chief of staff. He worried that the press would overlook the men sent to Siberia, and he liked the kind of stories Hull wrote, which he felt gave people at home a good feel for the life of an American soldier. As long as she had an editor to send her, he was willing to accredit her, even when it meant overruling the bureaucrats at the Office of Military Intelligence. When one of them told Hull that she shouldn’t even bother to submit an application, she left the office and returned an hour later with a memorandum signed by March stating, “If your only reason for refusing Miss Peggy Hull credentials is because she is a woman, issue them at once and facilitate her procedure to Vladivostok.”

On October 15, 1918, Hull sailed from San Francisco on a Japanese steamer. In her luggage she carried the first war correspondent credentials given to a woman by the U.S. War Department. An impressive document printed on heavy vellum and signed by the director of military intelligence, it assigned her to the headquarters of the American army in Siberia under the command of Major General William Graves. A month later, she arrived in Vladivostok, where she learned that the armistice had been signed a few days earlier. Graves, his 9,000 troops, and Peggy Hull were all in Siberia in pursuit of a military exercise that no longer had a clear purpose.

Hull spent nine frustrating months in Siberia. Her credentials did not give her greater access to the front line than she had as an unaccredited correspondent in France. Now she was hampered by the same restrictions as other correspondents.

Although she still inserted herself as an active player in the stories she reported, Hull dropped the playful “Peggy” persona in favor of serious reporting on conditions in Vladivostok, including a long piece on the behavior of American troops, who had taken advantage of easy access to cheap vodka, engaged in drunken brawls, wrecked a building, been involved in several reckless shooting incidents, and generally made themselves unwelcome to the residents of the city. At some level, it didn’t matter what she or any of her fellow correspondents wrote. American readers were more interested in peace negotiations at Versailles than a politically driven mission in a place that no one had heard of. She was just as eager to leave as any American soldier when the army prepared to withdraw its troops in the summer of 1919.

Hull with novelist Hobert Skidmore. One young officer suggested that she observe the war from a rocking chair. (From the Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas)

Between 1919 and 1932, Hull was a journalistic rolling stone. She worked as a reporter in Shanghai, then in Paris, then in Shanghai again. She made a second hasty marriage to yet another charming drunk—this time a British ship captain named John Kinley. When their marriage finally failed, she returned to the United States, where she discovered that she had lost her citizenship by marrying a foreigner. Supported by the National Women’s Party and her friends in editorial positions around the country, she fought a highly visible campaign to change the law and regain her citizenship.

While she battled the Immigration Service, she made the Hotel Bretton Hall in New York City her home base, from which she traveled as needed to cobble together work as a freelancer. In New York, she fell in love with an old friend from her days at the Denver Post: Harvey Deuell, now the managing editor of the New York Daily News. They wanted to marry, but Hull was still married to John Kinley. She was sure that an American divorce would be sufficient. Deuell was more cautious. He asked her to get divorced in Shanghai to be sure it was legal.

Hull arrived in Shanghai only days before the Japanese attacked the city on January 29, 1932, part of the undeclared war between China and Japan that had begun with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria four months earlier. She had never before reported on active combat. Now she had her chance. The New York Daily News did not have a reporter in Shanghai. Deuell cabled Hull: “Go to work; you’re our correspondent.” She filed her first report later that day.

For the next 33 days, Hull worked to the edge of exhaustion, writing and filing stories for the Chicago Tribune and New York Daily News syndicate, and regularly scooping her fellow reporters with the help of an acquaintance who owned a shortwave radio. She described bombings minutes after viewing them from the roof of a flour mill that she used as an observation post. She wrote about the misery of Chinese workers seeking shelter after Japanese bombs destroyed their homes, Buddhist temples transformed into shelters for the wounded, guerrilla warfare in the streets, and panic among foreign nationals who discovered they were as vulnerable as the rest of the city.

The fighting ended on March 3, and Hull filed her last story for the Daily News the next day. She never entirely recovered from her experience of reporting from a city under attack. Five years later, she wrote to a fellow journalist that “I still suffer from the noise and terror. … A door slamming violently makes me tremble before I have a chance to remember that it isn’t a shell or a bomb. I dread the sound of airplanes overhead and do not believe I will ever get over that feeling.”

But the residual nervous effects of her experiences in Shanghai weren’t enough to keep Hull away from the battlefront when the United States entered World War II, almost 10 years later. Her official press credentials had never been canceled, so she assumed that her main challenge would be finding a newspaper to sponsor her, since she had been out of the business since returning from Shanghai. After 11 months, she finally persuaded the editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer—the paper whose previous editor had declared he “wouldn’t be a party to sending a girl to an army camp”—to send her as one of its correspondents.

When she went to Washington, D.C., to apply for an assignment, she found she had a new fight on her hands. Though the War Department was slightly more accommodating about the question of women war correspondents, Hull’s age was against her. She was now in her mid-50s. One young officer suggested she’d be better off observing the war from a rocking chair “on the old front porch.” He was no more successful in discouraging her than his predecessors had been. Hull wore the War Department down, going to the accreditation office every day until the officer in charge gave up and handed her the application.

Instead of applying for a European assignment, Hull wanted to be sent to the Pacific theater of operations. Because of the time she had spent in China, she requested permission to join Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell’s command in Asia. It took him four months to respond with a single word: “No.” Never willing to give up, she applied to join the command of Lieutenant General Robert C. Richardson Jr. in Hawaii. She received permission five days later.

But when she arrived in Honolulu, she learned that Admiral Chester Nimitz, who did not want women in his theater of operations, had revoked a pass allowing Hull to travel by naval transport. Hull was restricted to Hawaii. As always, she adapted. She filed her first report from Honolulu in January 1944, under the byline Peggy Hull Deuell, having married a third time in 1933. Unable to get close to the action, she used the techniques that had served her well in France, combining her personal experiences with stories she heard from men who had recently returned to Hawaii from combat areas. She ate breakfast with the enlisted men at the mess hall. She told her readers about camping on flea-infested islands. She described what it was like to ride in a Jeep: “There is nothing to hang onto. You hold your seat by sheer wishful thinking.” She wrote heartbreaking accounts of the wounded men she visited in the hospitals on Oahu, and reminded her readers of the chronic homesickness that all “the boys” suffered.

In November 1944, Hull got permission to travel within the Hawaiian Islands and broaden the scope of her reporting. In January, she finally received authorization to travel around the islands of the Pacific theater. Allowed to follow the troops as soon as the nurses had landed, Hull now found herself in spots that were not quite pacified. After her first night in a camp in the Marianas, she woke up to the news that a Japanese soldier had been killed the previous night within a hundred yards of the tent where she slept. Not an unusual occurrence, a young soldier reassured her.

Marching with the troops on the Mexican border, Hull had slept on the ground wrapped in her poncho. Now she slept alongside the troops again, on a cot in one of the tents that stood “in orderly rows looking like small pyramids in the soft moonlight.” She responded to air raid alerts in the night, pulling on bathrobe, boots, and helmet as she ran to stand with the soldiers in “a long narrow slit which resembled nothing so much as an open grave.” And yet, writing to an old friend from a recently pacified island in the Marianas, Hull reported, “Never in my life have I enjoyed each day as much as I do now. No one could ever have convinced me that such an age could possibly bring such sheer pleasure in living.”

Hull knew that at such an age she was lucky to be “over there.” She envied and admired the young women who served, particularly the first nurses to land in Saipan, whom she described as “young hardy brave soldiers perfectly competent to look after themselves.” She laughed when a young officer, who had plans with a hot date, asked her to entertain a visiting older British general for him on the thin grounds that she could understand the general’s jokes. In an earlier war, she would have been the date, the sweetheart of the troops. Now she was a mother figure who mended uniforms, comforted wounded soldiers, and listened to her boys tell stories about home, comrades, and war.

Her age was now a benefit as well as a burden. During her time in the Pacific, she earned a deeper love and respect from the young men whose stories she told. Over the course of the war, they showed their affection for her by giving her patches from their units, which she wore on large berets that became her trademark—an unorthodox addition to the official uniform for female correspondents. Also unorthodox: the three campaign ribbons she proudly wore that designated her presence in the Mexican Punitive Expedition, World War I France, and the Siberian Intervention. No other woman correspondent could claim the same history.

Hull received her first patch in the spring of 1944 from PFC Frederick White of Wellington, Ohio. “You seem to like our outfit,” he told her. “We thought you might not mind being adopted.” By the war’s end, she owned seven berets, covered with 50 patches that had been presented to her by men of every rank from every service.

When the war ended in August 1945, Hull went home and hung up her berets. Her days as a war correspondent were over, but she was not entirely forgotten. In April 1946, she received a special commendation, signed by Rear Admiral H. A. Miller and Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, “For Outstanding Performance and Service Rendered to the United States at War, as an Accredited Navy War Correspondent.”

Hull summed up her own career in a column for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, dated August 20, 1944:

There will be no scoops, no prize awards, no Purple Hearts or memories of desperate hours well shared with brave Americans. I am a woman and as a woman am not permitted to experience the hazards of real war reporting. After a long and varied experience in the First World War, on the Mexican border, in France, Siberia and China, these restrictions have laid a heavy hand upon my dreams. But I have found work to do. There [are] the little stories to write—the small, unimportant story which [means] so much to the G.I. …

Hull, who died in 1967, underestimated the importance of that work. “You will never realize what those yarns of yours … did to this gang,” one soldier wrote to her in August 1944 from the Pacific atoll of Makin, after reading her account of his unit’s experience digging a well there. “Nothing but a 30-day furlough or a shipload of beer could have topped the lift they got. You made them know they weren’t forgotten.”