The Baddest Man in Town

On the trail of a historical figure immortalized in African-American folklore

On Christmas night 1895, at Bill Curtis’s notorious St. Louis saloon, a gun-toting carriage driver named Lee Shelton shot and killed his friend William Lyons. According to an account of the incident in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, “an argument was started” between the heavy-drinking hotheads, “the conclusion of which was that Lyons snatched Sheldon’s [sic] hat from his head. The latter indignantly demanded its return. Lyons refused, and Sheldon drew his revolver and shot Lyons in the abdomen. … When his victim fell to the floor Sheldon took his hat from the hand of the wounded man and coolly walked away.”

That night, a man died and a legend was born. Shelton—alias Stack Lee—would be memorialized in song, becoming perhaps the most significant figure in African-American folklore. In a 1911 article in the Journal of American Folklore, the sociologist Howard W. Odum presented several versions of the song, which he’d been collecting throughout the American South:

Stagolee killed a man an’ laid him on de flo’,

What’s dat he killed him wid? Dat same ole fohty-fo’.

Oh dat man, bad man, Stagolee done come.

Mississippi John Hurt, Cab Calloway, Woody Guthrie, James Brown, Wilson Pickett, Tina Turner, Bob Dylan, and Beck are among the hundreds who have sung a version of Stagolee’s story. Lloyd Price took a rollicking rendition of “Stagger Lee” to the top of the pop charts in 1959. Such brushes with mainstream success never compromised Stag’s street cred, though. In bars, barbershops, and prisons, he remained “the baddest n—– who ever lived,” the antihero of profane epics and rhyming “toasts” whose exploits offered a fantasy of freedom from life’s indignities. Stagolee haunts the prose of Richard Wright and Toni Morrison; James Baldwin worked on a novel about the character and late in his life published a long poem called “Staggerlee Wonders.”

Scholars of African-American studies generally agree that both the pimp protagonists of ’70s blaxploitation films and the self-mythologists of gangsta rap are Stagolee’s direct descendants: mononymous, fearless, and fastidious about their name-brand apparel. In their New Book of Rock Lists, Dave Marsh and James Bernard name 15 “Sons of ‘Stagger Lee’—Records That Would Be Inconceivable Without Him,” including the Geto Boys’ “Mind of a Lunatic,” Cypress Hill’s “How I Could Just Kill a Man,” and Ice Cube’s “The N—a You Love to Hate.”

Despite the tendency of folktales to grow taller, the canonical Stagolee story has remained impressively stable over the years: Stagolee is a “bad man” who objects to Billy Lyons’s stealing his Stetson. Billy pleads for his life, invoking his wife and young children, but Stag pitilessly executes him, usually with a .44. It’s strikingly close to what actually happened, right down to the names of the principals and the caliber of the murder weapon. Turn-of-the-century St. Louis was a musical place—the cradle of ragtime, full of “barroom bards” and river roustabouts who were constantly turning scuttlebutt into song. It was not unheard of, in other words, for the day’s news to pass from fact into folklore almost instantaneously, trapping many authentic details in the amber. The events that inspired the murder ballads “Frankie and Johnny” and “Duncan and Brady” occurred within a few years, and a few blocks, of the Stagolee killing.

What about Stag’s “bad man” reputation and Billy’s wife and children, though? Researchers have tended to conclude that those two elements of the myth are songwriters’ embroideries. Lee Shelton had no prior criminal record that anyone could locate, and William Lyons was listed as single on his death certificate. But over the past several years, through services like Newspapers.com and Ancestry.com, huge caches of relevant documents have become broadly available—and, crucially, keyword-searchable—for the first time. A couple of summers ago, I started poking around in those collections, and once I started comparing what I thought I knew about the Stagolee legend with what I was seeing in the documentary record, I found that I couldn’t stop.

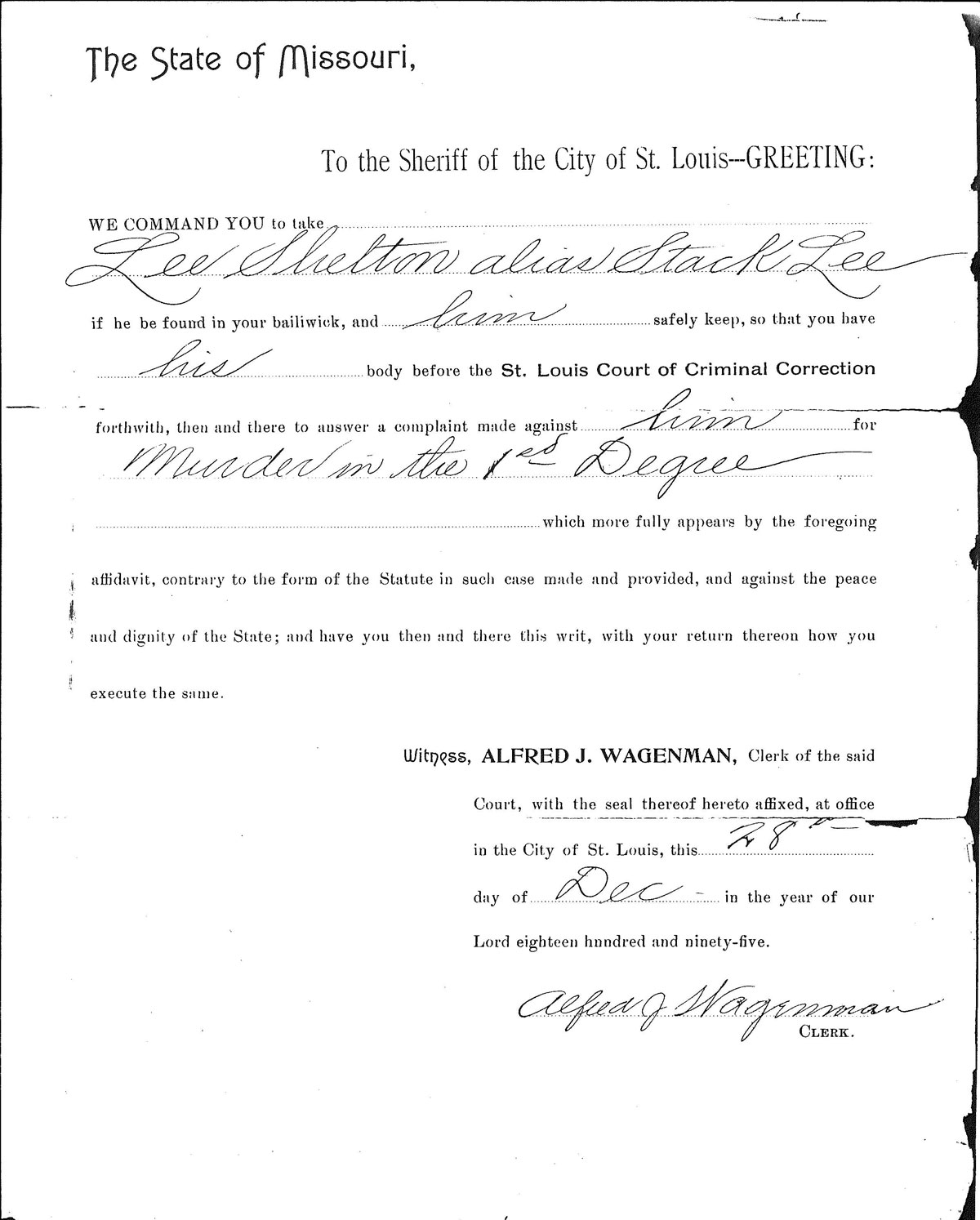

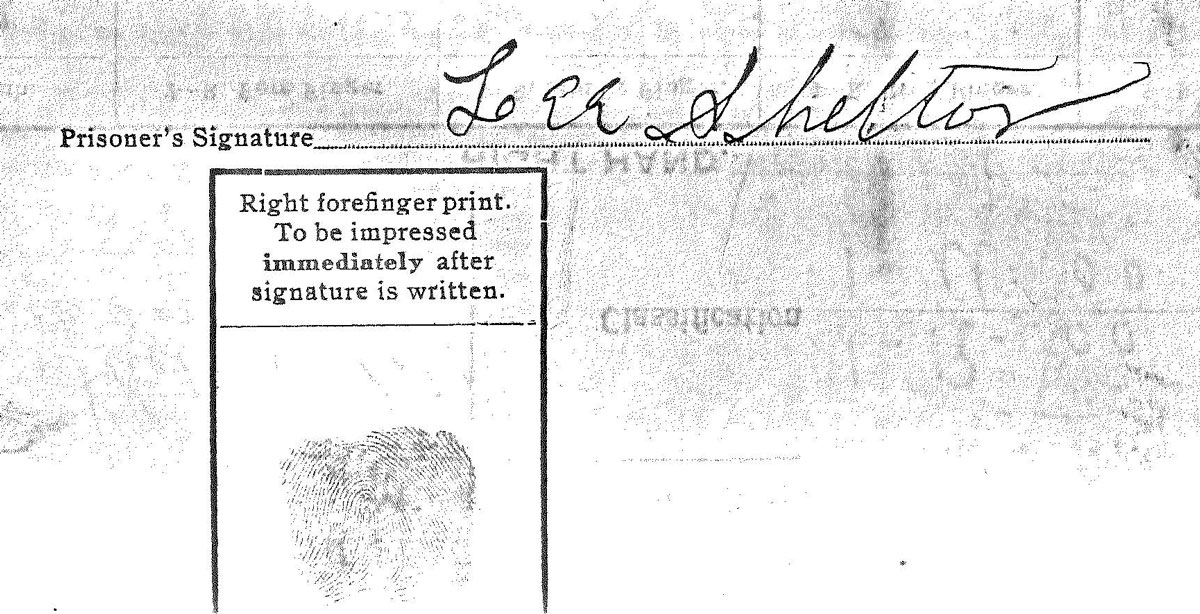

Lee Shelton’s signature and fingerprint from his penitentiary records (from the papers of John Russell David)

In the refrain of his definitive 1928 version, Mississippi John Hurt sings, “That bad man, oh cruel Stack O’Lee.” That the word bad is a versatile one, especially in African-American vernacular English, has allowed the tone of the songs to shift over the course of the 20th century—from disapproving to approving of Stagolee—without their essential vocabulary ever changing. But whether the word is used to celebrate or censure Stagolee, the implication of “bad” is always that he’s dangerous and widely feared. George M. Eberhart, probably the most meticulous Stagolee scholar, calls this a slander on Lee Shelton. In his 1996 essay “Stack Lee: The Man, the Music, and the Myth,” he cites evidence that Lyons was the more belligerent of the two men and that Shelton probably shot him in self-defense. “The original Stack Lee may have been a petty thief and gambler,” Eberhart writes, “but he was no murderer, much less the bloodthirsty, heartless bad man perpetuated in myth and music. After a century of vilification, it’s time to separate Lee Shelton the man from Stackolee the myth.”

A few Newspapers.com searches, however, reveal that Lee Shelton was indeed a serially violent man, even by the standards of the city’s “Bloody Third” district. Now, the journalism of the day was appallingly poor—a hodgepodge of hack reporting, rumor, speculation, and opinion, seasoned liberally with racism. But the sheer ubiquity of Stack Lee’s name in the crime pages is impossible to explain away. In 1889–1890 alone, he was arrested for assault with intent to kill on three separate occasions. In November 1894, he beat a man with a revolver, fracturing his skull and inflicting “five severe scalp wounds.” Less than two months later, he “fired a shot without effect at Thomas Gibson.” He then hit Gibson over the head with the butt of the gun. By the time he faced off with Billy Lyons the following Christmas, pistol-whipping had become his specialty; at the coroner’s inquest, three witnesses said that Shelton struck Lyons with the .44 before shooting him. He was also booked at various times for stealing a gold watch, carrying brass knuckles, and getting caught in an opium joint. In 1892, after he was detained for robbing a woman with whom he’d been living, the Globe-Democrat called him “notorious.” The denizens of the Bloody Third probably just called him “a bad man.”

How was he able to terrorize the city for close to a decade without acquiring a rap sheet? Or, as Mississippi John Hurt puts it,

Police officer, how can it be

you can ’rest everybody but cruel Stack O’Lee?

The simplest answer may be racism. Violent crimes were much less likely to be vigorously prosecuted if their victims were Black, as Shelton’s almost always were. An 1896 Globe-Democrat article reveals an attitude among white St. Louisans toward the killing of Blacks that could fairly be called genocidal: “Though the Morgue and the City Hospital are regularly supplied with subjects from [Curtis’s saloon] … it is generally conceded that he is acting as a public benefactor in allowing undesirable members of colored society to be dispatched in his place of business.” The reason Shelton finally went to prison, in all likelihood, wasn’t that he’d killed a man but that he’d killed the wrong man. Billy Lyons was the brother-in-law of Henry Bridgewater, an influential saloon owner and by some accounts the wealthiest Black man in St. Louis.

Stack Lee was also well connected, which may further explain his having gotten away with so much for so long. According to the Globe-Democrat, his trial for Lyons’s murder had to be pushed back because the two chief witnesses couldn’t be found: “Deputy Sheriff Ruler said he had reason to believe that [the witnesses] had been paid to leave the city. Shelton is very popular with those of his class in the Third Police District, and is not without funds.”

By the time his first trial ended in a hung jury, Shelton was already the subject of a popular prison ballad. In early 1897, a reporter for the Kansas City Star transcribed some songs “often rendered by the negro prisoners” of the city jail, including “ ‘Stacka Lee,’ an importation from St. Louis”:

Stacka Lee, can’t you see

That it’s murder in the first degree?

O how I wonder what they’ll do

When Stacka Lee has his trial thro’.

Shelton was ultimately convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 25 years in the state penitentiary. He was paroled after serving about half of that but returned to prison for good in 1911, following a home invasion and robbery in which he once again fractured his victim’s skull with a pistol.

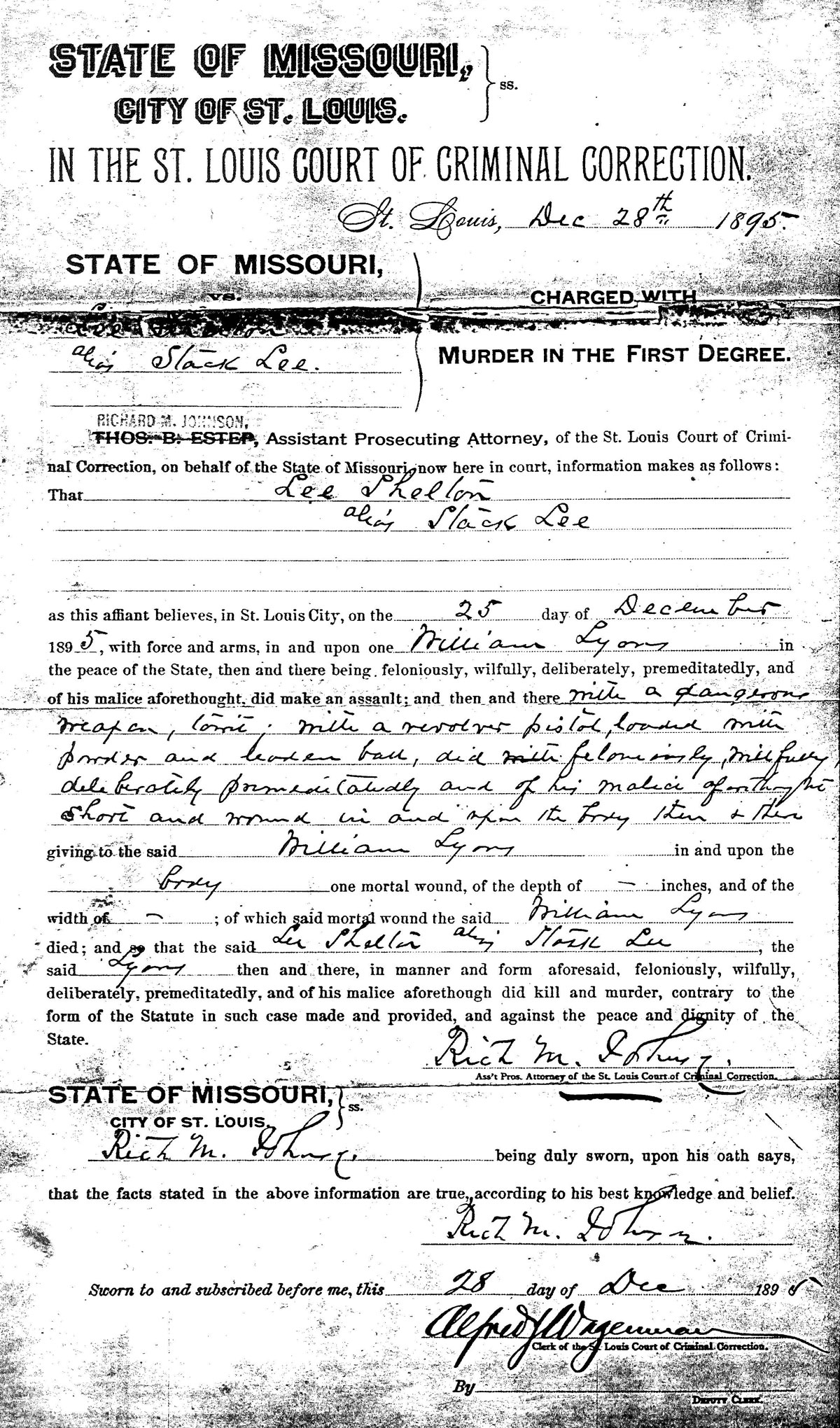

The State of Missouri charged Lee Shelton, alias Stack Lee, with the murder of Williams Lyons (from the papers of John Russell David)

For all their stylistic and thematic variety, the songs are nearly unanimous that Billy Lyons had a wife and kids. He always addresses Stagolee, and it’s always some version of the same two-sentence appeal:

Please don’t take my life.

I’ve got two little babies and a darlin’, lovin’ wife.

John Russell David was a graduate student in the early 1970s when he first uncovered the St. Louis origins of “Stagolee” by talking to a Black octogenarian who remembered the murder. “According to the testimony given the Coroner,” David writes in his dissertation, “Lyons made no appeal for his wife and children. Lyons’ death certificate classifies him as single. In none of the official records or newspaper accounts is mention made of the children or ‘lovin’ wife’ of William Lyons.”

But in 1979, shortly after the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published an article about his research, David was contacted by Susie Mae Myles and Arthur Buddy Johnson, two St. Louisans who credibly claimed to be the great-grandchildren of Billy Lyons. According to them, Lyons had married a southern woman named Lena Northcross. She’d died not long after Billy did, orphaning their three children: Marie, Leon, and Florence, the daughter from whom Myles and Johnson said they were descended. David interviewed them extensively and found documentary support for their claim. The death certificates of both Marie and Florence, for example, list Lyons as their biological father. David planned to reveal their story in a book adapted from his unpublished dissertation, but he was diagnosed with an aggressive cancer in 1986 and died early the following year. All of his Stagolee research—boxes of criminal complaints, prison records, clippings, correspondence, photographs, floppy disks, and audio tapes—had been sitting in a St. Louis basement ever since. When I contacted David’s widow, Judith, in the summer of 2019, she asked if I’d like to have it.

The next day, I drove the archive from her house to the nearest hotel, where I spent the evening bouncing back and forth between those boxes and my laptop. My first Ancestry.com search, on the promisingly unusual name Lena Northcross, returned an 1883 marriage license from Tennessee. When I ran my cursor over it, the name of her betrothed appeared: “Wm C Lyons.” I opened the document and stared at his signature, thinking, I am the only living person who knows Billy Lyons’s middle initial.

There can be no doubt that Susie Mae Myles and Arthur Buddy Johnson were the great-grandchildren of Billy Lyons. Reluctantly, I admit to having doubts about their great-grandfather’s being that Billy Lyons. In a typescript draft of David’s book, I found the following: “Surviving documents … record that two of the Lyons children—Florence and Marie—were already in St. Louis’ Colored Orphans Home by May of 1894 where they were baptized by Father Cassius Mason of All Saints Episcopal Church. William and Lena Lyons, the children’s parents listed on the baptism record, were not present.” Uncharacteristically, David included no footnote, although the heavily hand-edited page is clearly not from a final draft. I haven’t been able to track down the “surviving documents” he apparently saw. But the fact is that when children live in an orphanage, they’re usually orphans. The William Lyons who failed to attend his kids’ baptism in 1894—a year and a half before the Stack Lee murder—may have had the excuse of already being dead.

In David’s taped interviews, Myles and Johnson seem confident that their great-grandfather died in Curtis’s saloon that Christmas night. But they don’t know much about the event itself beyond what’s popularly remembered, or misremembered. They both believe, for example, that Stack and Billy were fighting over a craps game—a canard that made its way into the songs after being falsely reported by the papers. At one point, David asks Myles when she first heard the family story about Stack Lee and Billy, and she says, “Well, a song came out.” When he invites Johnson to share the family’s version of the legend, Johnson sings—in a beautiful, mournful voice—the lyrics to Lloyd Price’s number-one hit.

Myles and Johnson both died in the ’80s, and neither had surviving children. Following a breadcrumb trail of birth announcements and census records, I tracked down the children of their sister, the late Rosealee Johnson Pearson. Several of them knew their lineage as far back as Florence Lyons, but not her father’s famous name. And they were acquainted with the story of Stagolee, but as legend, not family history. LaTonia Pearson, the great-great-great-granddaughter of William Lyons and Lena Northcross, told me that her grandmother Rosealee “wouldn’t have been inclined to share something so negative with her children.”

It’s hard to draw any confident conclusions from all this. The Pearsons of St. Louis may be living proof that Billy Lyons had a wife and kids. Or they may be descended from another Billy Lyons altogether, whose death orphaned three young children and left a vacuum of information in which family lore and folklore would eventually merge.

There’s also Billy’s stepdaughter to consider. In January 1896, according to a Post-Dispatch item that escaped the notice of earlier researchers, a young woman named Stella Casey took her own life by swallowing a box of rat poison. The personal traumas that allegedly drove her to do it included “the recent slaying of her step-father, William Lyons, by Lee Sheldon [sic].” The shoddiness of 19th-century journalism makes me skeptical of anything reported only once. Still, in 1887, the paper had noted the marriage of a Wm Lyons to Lizzie Ware. And that same Lizzie Ware, per the 1880 census, was a young African-American widow with two daughters: Ada (age five) and Estella (age eight). In other words, there was a Black man named William Lyons with an adult stepdaughter named Estella living in central St. Louis around the time of the Stack Lee killing.

So there are actually two plausible narratives in which Billy Lyons left behind a wife and kids. Marriage and birth dates make them difficult but not impossible to reconcile, and if either one is true, then so are all those song lyrics.

A question that almost everyone who writes about Stagolee eventually takes up is, Why are we still talking about this particular murder? Turn-of-the-century St. Louis was a shockingly violent place. Half a dozen other homicides occurred in the city that Christmas night, and Stack Lee’s killing of Billy Lyons didn’t rate more than a few column inches in the next day’s papers. Why did this seemingly unexceptional crime enter our folklore, and remain there, when a million others faded from memory? “Because somebody wrote a catchy song,” it’s tempting to say. But the best-known versions of “Stagolee” sound nothing like one another; there’s no signature melody or even a common refrain to lodge in the cultural consciousness. And that answer wouldn’t account for the popularity of Stagolee “toasts”—proto-rap narratives delivered without musical accompaniment. Clearly, it’s the story that has had the staying power, along with the swaggering Stagolee character that the story introduced.

I think the answer to this question (and to the related question of what Stagolee tells us about how legends and folklore are passed down) may lie in the social function that Stagolee serves. At the turn of the century, with emancipation receding into memory, African Americans were confronting the new limits of their liberty in a poisonously racist country. The “bad man” emerged in their stories and songs as an alternative to more wholesome folk heroes like John Henry. Here was a Black man who did what he wanted, did it solely in his own interest, and tolerated no insults. The scholar John W. Roberts says that such figures exist “more as a projection than a role model,” providing “an expression of wish-fulfillment … a safety valve or release.” Into this historical moment strode “Stack Lee” Shelton, a notorious “bad man” with a memorable name who would leave your children fatherless if you tried to steal his Stetson hat. This was ready-made folklore—a set piece for which every essential prop had been provided. The mythmakers’ work was already done.

Because that need for vicarious freedom never went away, Stagolee then stuck around for a century, with an occasional aftermarket modification to reflect the tastes of the day. Starting in the 1960s, for example, the Stetson hat, more closely associated with white cowboys than Black hustlers, was replaced in many versions of the song by a Cadillac. As Cecil Brown puts it in his book Stagolee Shot Billy, “One reason Stagolee has survived so long is that any performance of it grants the participants—performers and audience alike—‘time out’ from the pressures of life in a racist American society.”

Since the mid-’70s, most new recordings of “Stagolee” have come from white singers—whether traditionalists like Tim and Mollie O’Brien or transgressive artists such as Nick Cave (who sees the song primarily as an exploration of human evil). It’s no coincidence that Stagolee faded from African-American folklore just as a new wave of well-dressed “bad muthafuckas” arrived on the scene, also rolling Cadillacs. The original bad man has been supplanted by the multitudes he always contained—first Dolemite, Shaft, and Super Fly, then Ice Cube, 2Pac (who once threatened his rivals, “My .44 make sure all y’all kids don’t grow”), and Gucci Mane, who literally killed a man for trying to steal his gold chain and then bragged about it on a track. Stagolee’s work is done, too.

Lee Shelton may have had a wife of his own. She hasn’t remained central to the story the way Billy’s family did, but Mrs. Stagolee haunts early versions of the song. When she’s given a name, it’s often either Lillie or Nellie Sheldon. In John Russell David’s papers I found what’s almost certainly the oldest published sheet music—“Stack-O-Lee (A True Story From Life),” copyright 1910, by the cringe-worthily named Three White Kuhns. It includes the verse,

When little Lillie Sheldon she first heard the news

She was sitting on the bedside lacing up her shoes

Ev’rybody body talk about Stackolee.

This set of lyrics circulated widely in the ’20s and ’30s, with the real Stagolee’s slightly misspelled surname hiding in plain sight for decades.

Interestingly, a single news item from 1896 includes the name of Stack Lee’s girlfriend, and it’s Lillie Moore. Did she later become Lillie Shelton? It has long been known that Lee Shelton was listed as married on his death certificate. Researchers have tended to write that off as a likely error, though, since he was single at the time of his incarceration, according to penitentiary records. But maybe that was the error. Or maybe he got married while in the pen, or while out on parole in 1910. What’s been missing is any corroborating evidence that isn’t a song lyric.

Except that the evidence hasn’t been missing; it’s just been missed. In the St. Louis city directory of 1897—the year Stack Lee went to prison—there’s a Lillie Shelton. And here’s the kicker: she was living at 914 North Twelfth Street, which, according to the Globe-Democrat, had been Lee Shelton’s home address on the day he killed Billy Lyons two years earlier. The odds that this is a coincidence are infinitesimal. Stack Lee may or may not have been legally married, but “Little Lillie Sheldon” was no songwriter’s invention.

Stack Lee died of tuberculosis on March 11, 1912, five days shy of his 47th birthday. If he and Lillie were indeed married at the time, they were no longer close. Stack left everything he owned to his good friend James D. Anderson, a junk dealer, in whose home he was supposed to spend his final days. Apprised of Shelton’s terminal condition, Missouri Governor Herbert S. Hadley had approved a mercy parole, “upon condition, however, that he in the future … conduct himself in all respects, as a law-abiding citizen. Upon Shelton’s arrival in St. Louis he will at once report to Mr. James D. Anderson.” It never came to that. Stack Lee passed away in the prison hospital, wasted by his illness to less than 100 pounds. That’s one detail that the songs, understandably, have tended to get wrong, insisting that the bad man went proudly to the gallows.

Less than a year later, Anderson’s ramshackle brick house was raided by police, who discovered what an IRS agent called the largest cocaine and opium distribution plant in the United States. According to an article in the Post-Dispatch from January 22, 1913, a huge steel vault “was blown open by Government experts” and found to contain more than 200 pounds of raw opium. “Signal gongs and electric wires to warn the operators of danger had been strung about the place. The factory was guarded by two vicious bulldogs.”

Shelton’s parting gesture, in other words, was to will his meager possessions to the biggest drug kingpin in St. Louis. I’ve tried to refrain from any mythologizing of my own, but I can’t help conjuring a scene: a prison official asks Stack Lee, bedridden and skeletal, if the friend into whose care he’s being paroled is a respectable citizen who makes an honest living. And Stack answers, with an almost imperceptible smile, “Yes. He’s a junk dealer.”

John Russell David died almost exactly 75 years later at almost exactly the same age—just a few months past his 47th birthday. He, too, believe it or not, had tuberculosis. It had remained latent in his lungs for several years, but the chemotherapy he needed for a bone marrow transplant weakened his immune system, forcing him to take an enervating TB medicine. His doctor believed he’d been exposed to it while doing fieldwork for his dissertation in the early ’70s. “He visited so many nursing homes,” his widow told me. It’s a heartbreaking story, but also a testament to David’s love of the legends and his determination to get as close to their sources as possible—a doggedness that makes all my laptop sleuthing look like dilettantism. Judith was nearing 80 and trying to downsize when I contacted her two summers ago. It may have seemed like providence when a Stagolee-struck researcher, also 47, showed up on her doorstep, hoping literally to carry out her late husband’s work.

I’m still awed and humbled, every time I pick through those boxes, by the artifacts he was able to unearth. Here’s the original arrest warrant. Here are prison records with Stack Lee’s signature and fingerprints. Here’s a handwritten letter from Billy Lyons’s sister and mother, pleading with the governor to deny Stack Lee a pardon. And here is the tape of David interviewing Ed McKinney, an elderly musician with an encyclopedic knowledge of St. Louis history.

I had to borrow cassette players from three different friends before I found one that would play the 90-minute Memorex, which is actually a dub of a reel-to-reel recording from 1973—a 40-year-old copy of a 46-year-old conversation with an 88-year-old man. Despite what had come to seem like long odds, when the spindles finally turned, the sounds that emerged were intelligible:

“Yes, I remember Stackalee,” McKinney says, and David clearly thinks he’s referring to the song.

“Yeah, but I wonder if there was ever a person whose name was …”

“Stackalee’s name was Lee Shelton.”

Pause.

“Lee Shelton? I never heard that before!”

McKinney was born in 1885 and sounds like it. His voice is arid, his speech halting but extravagantly precise. “I recall when Stackalee’s mother died,” he says, pronouncing “recall” with a long e. “The guard from the Missouri Penitentiary brought Stackalee, whose name was Lee Shelton, to his mother’s funeral, at the Metropolitan A.M.E. Zion Church, which was at 2625 Morgan Street.”

David, who sounds a little like Jim Henson, doesn’t try to conceal his excitement. “You son of a gun!” he says. “Gosh almighty. Because no one knows where that song really originated!” He tells McKinney that even Nathan Young, the dean of St. Louis folk historians, hadn’t heard of the real Stagolee: “I said, ‘Was he a real person?’ And he said, ‘Oh no, he was a folklore character.’ ”

McKinney laughs and laughs at that.

Listening to their exchange for the first time was a singular privilege—hearing, muddily but unmistakably, the precise moment when Stagolee stepped from folklore back into fact.

Listen to a clip from John Russell David’s 1973 interview with Ed McKinney, and be sure to read Eric McHenry’s annotation to the murder ballad’s oldest known lyrics.