Alphabet of Despair

The photographic language of Dorothea Lange conveyed order and beauty in a dusty, impoverished America

In November 1938, Dorothea Lange snapped a black-and-white photograph at a gas station in Kern County, California. A couple of buildings and trees are visible in the background—vague signs of life. In the foreground we see an air machine, made of wood and resembling a bedroom wardrobe, its door swung open to reveal a tangle of black hose inside. A sign atop the machine reads, “AIR.” And on the inside of the door is a large, hand-painted message.

air

this is your

country dont

let the big

men take it

away

from you

Look at the picture long enough and the word “AIR” starts to seem odd. For me, the letters drift apart, and I’m suddenly unsure how to spell or even pronounce the word. Repetition and capitalization contribute to the disorienting effect.

On this early June day, as I sit at my desk writing about Dorothea Lange, the air is in fact odd. Wildfires in Canada have sent smoke over the northeastern United States, creating an ashen sky that smells like burning. Yesterday, windows in my studio cast rectangles of amber light on the floor even though the sky remained an acrid gray. For the first time, I can imagine some of the horror of the Dust Bowl experience that Lange photographed in the 1930s, the sun blocked out for days and the air deadly and thick. It’s funny in a way to have photographed an air machine at such a time, a machine intended for filling the deflated tires of cars carrying families fleeing west—a machine to keep you going. But when the sky itself is toxic, it takes on another meaning. “Air,” it pleads, like a patient awaiting a ventilator. “Air,” it shouts, like a curbside huckster. It’s all anyone wants: air. You can almost imagine another machine just outside the frame that says “water,” and perhaps others farther down the road offering “food” and “shelter”—vending machines for life. Insert a nickel and get everything you need. And yet, on closer inspection, the air hose in the machine Lange photographed doesn’t appear to attach to anything. Like everything else in the catastrophic collision of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, it seems to be broken.

“Dorothea Lange: Seeing People,” an exhibition that runs from early November through March 2024 at the National Gallery of Art, assembles some of the photographer’s best-known and most poetic images. Beginning in 1919, with Lange’s intimate portraits of wealthy clients and artists in San Francisco, the exhibition includes the years in which Lange turned away from her photography studio and found employment with her second husband, Paul Taylor, at the newly established Farm Security Administration (FSA). The FSA was first known as the Resettlement Administration, created by presidential order in 1935 with hopes of appeasing progressives upset by the Department of Agriculture’s failure to provide aid to poor, rural farmers. Its goals included resettling those farmers on better land, providing grants and loans for modernization, educating farmers on nutrition and hygiene, and providing medical care. Along with nine other photographers sent out across the United States, Lange was assigned to document rural poverty. The goal was to provoke sociopolitical change by bolstering support and funding for FDR’s New Deal programs.

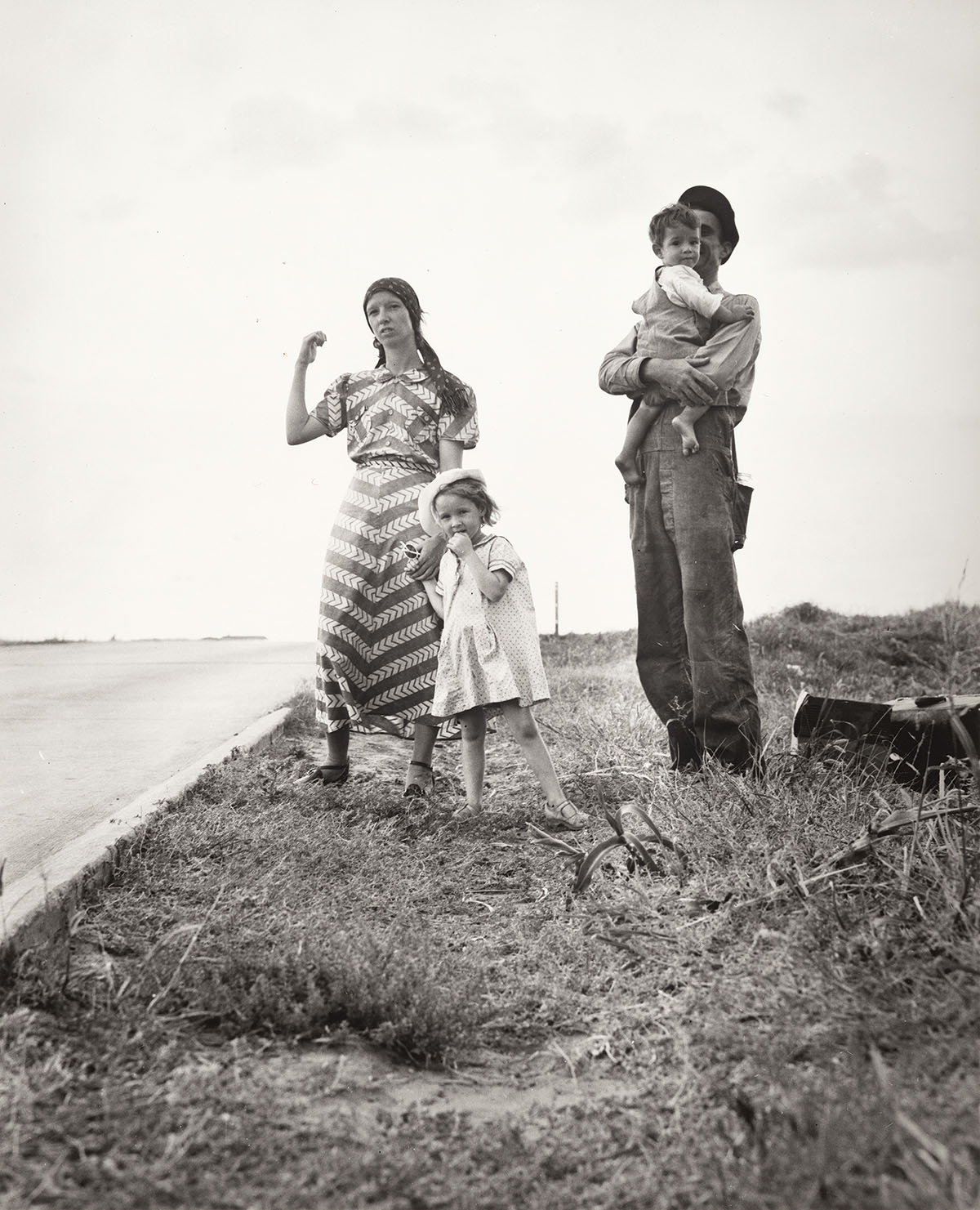

Lange embarked on a rugged, itinerant, often grueling life in some of the most desolate and hopeless places in the United States. She traveled mostly by car, pulling over to photograph things that caught her eye (landscapes, machines, signage, landmarks), milling about, hauling equipment, starting conversations. She seemed infatuated with the camera’s ability to dispassionately record the facts just as they were. Often, however, she would ask the people she met to pose for her, directing them, choreographing.

Everywhere she looked, Lange seemed to find repeating shapes, lending her pictures an ordered, geometric clarity and a striking modernist aesthetic. This is surprising given the disarray of the world she photographed, and it is part of what makes her pictures so unusual and strangely reassuring—as if she could see an ordered world subtending the world we actually inhabit, an invisible grid to which shapes snap. Whatever the condition of life (poverty, displacement, racism, despair, environmental disaster), Lange’s figures seem whole and not broken.

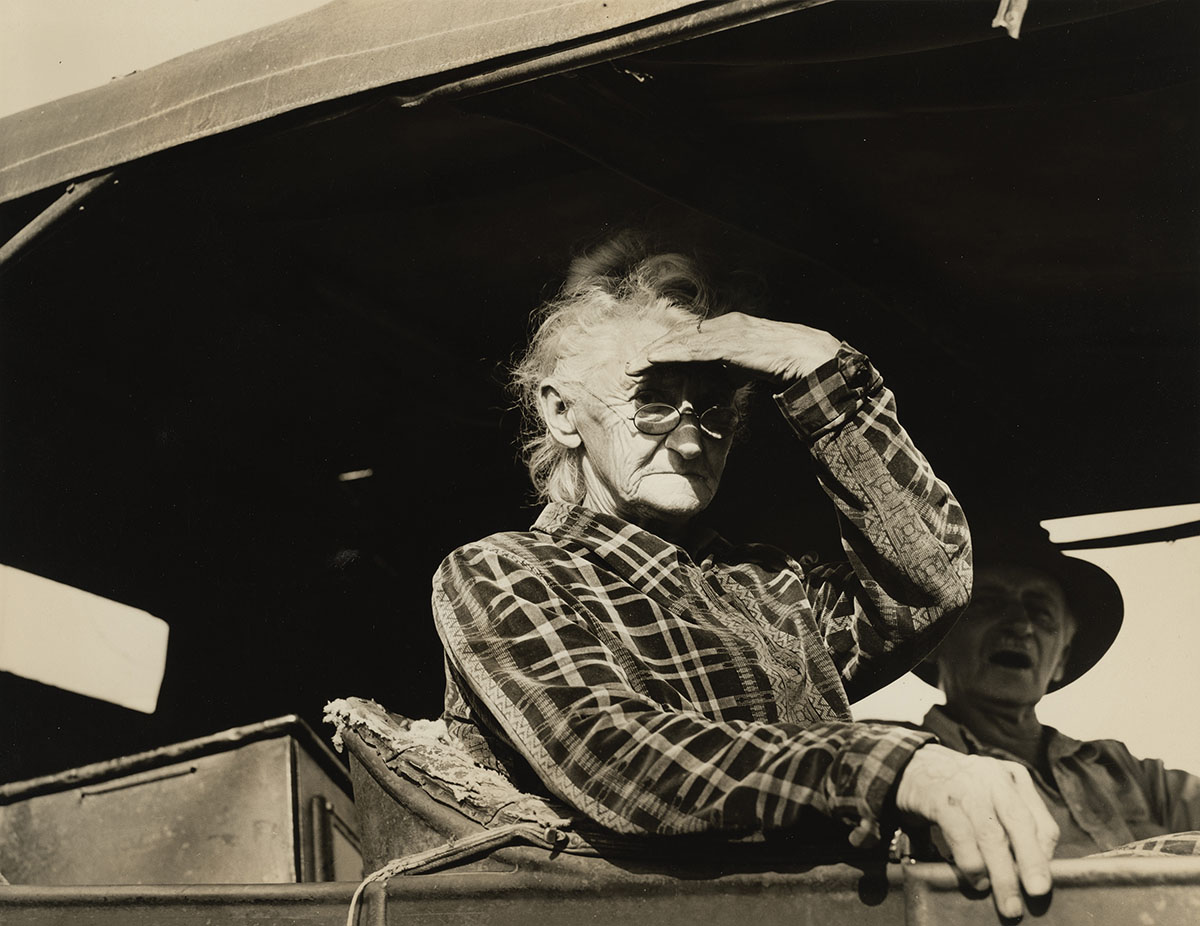

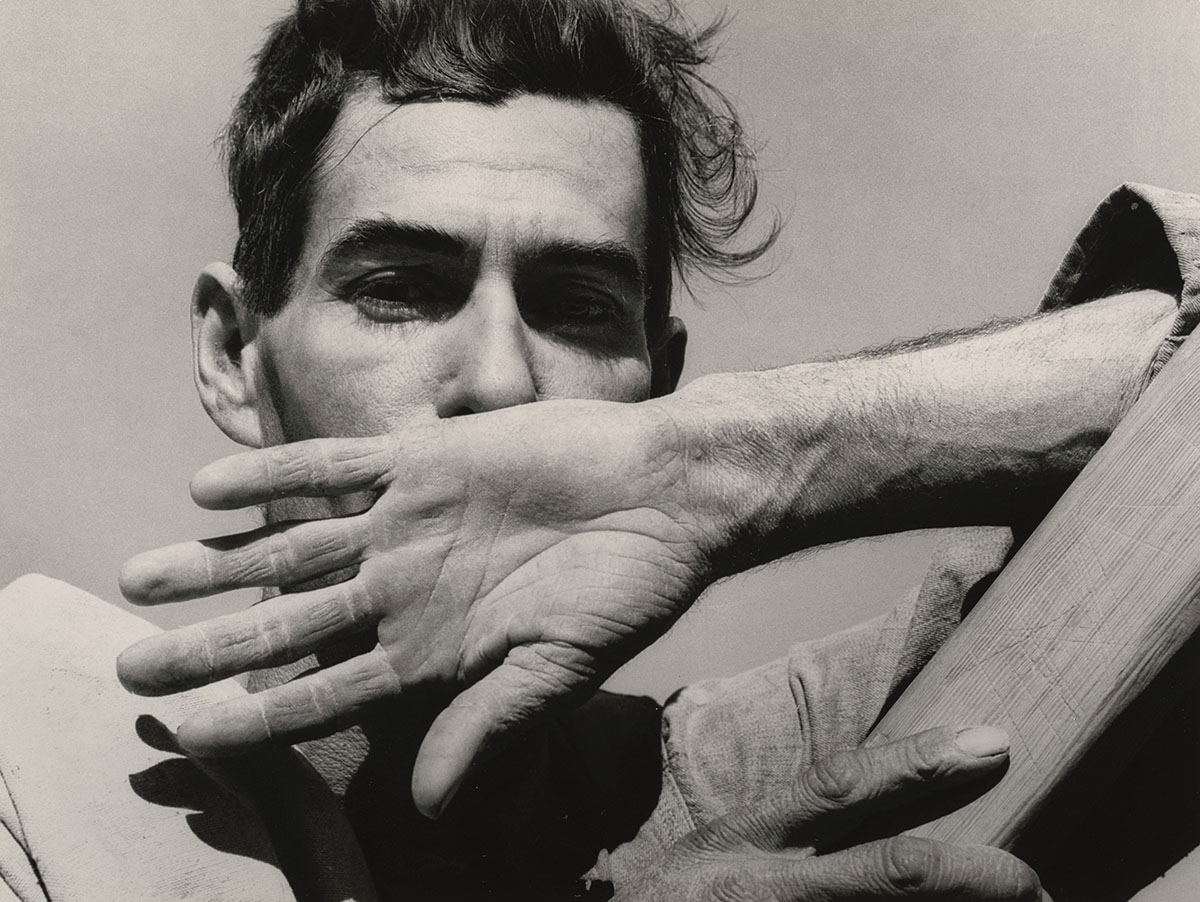

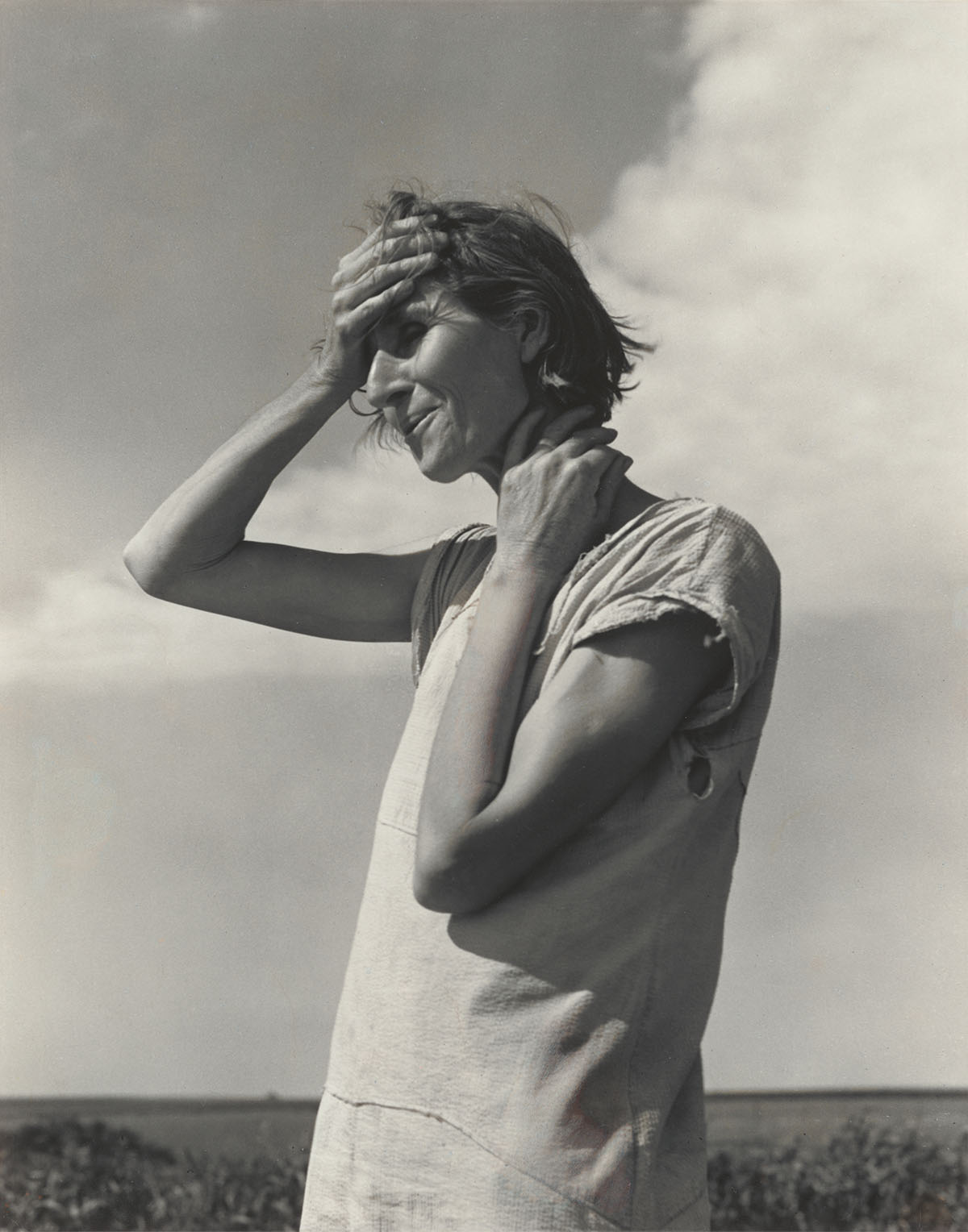

Different shapes have their own emotional tenor. Circles can be hopeful or maddening. Lange finds them in windows, tires, hats, heads, mouths, hunched figures, glasses, hands, and curled fingers. Rectangles seem blunt and reliable, if a little hard-edged. Conveying stability but also resignation, sadness, and gravity, rectangles appear in clothed bodies, feet, car doors, buildings, and signs. Triangles, emblems of angular hierarchy, indicate power and balance. But they also appear charged with passion, rage, or desire. In addition to capturing rooflines and oversize hats, Lange often highlights the way a body intersects with itself or something else, with triangles formed out of bent arms, tools, cotton sacks, or legs: shapes within shapes emerging from negative space.

Consider three photographs depicting women of various ages. The first is of an 80-year-old woman residing in a squatters’ camp near Bakersfield, California. In the second, we see Nettie Featherston, the wife of a migrant worker in Texas. And in the third, a young girl in Kern County pauses while picking and sacking potatoes. In each case, the figures shield their eyes, their raised arms creating the shape of a triangle (framing sky in two cases, the dark roof of a car in the other). These photographs have a way of accentuating and elongating the subjects’ arms, particularly the bare arms of Nettie Featherston, one hand on her forehead, the other clasping her neck, her downcast eyes pitted in shadow. The shape outlined by her arm in the air echoes that of the billowing white cloud behind her. Meanwhile, her bent arms together make a tilted W. She’s hot, tired. The sun makes it impossible to look directly at the camera. The tight line of her mouth arches ambiguously, so that even though her body conveys elemental exhaustion, it’s hard to know whether she is about to smile or cry. We know from Lange’s caption that Nettie Featherston and her family were near starvation, that they’d sold their car and burned beans for heat during a spring snow. “This country’s a hard country,” Lange notated. “They won’t help bury you here. If you die, you’re dead, that’s all.”

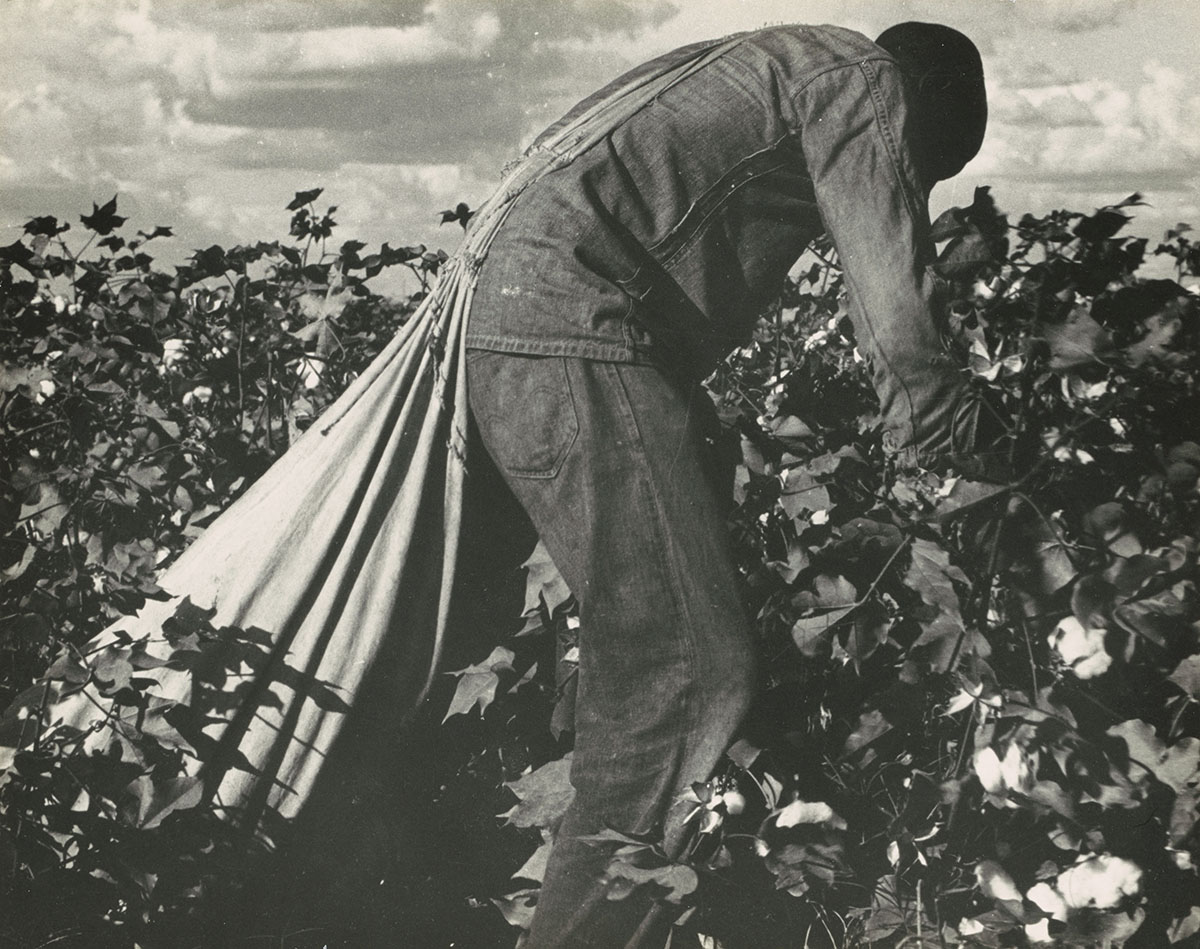

In another photograph, the hunched body and trailing sack of a fieldworker picking cotton in California’s San Joaquin Valley makes a lowercase h. Look at three other similar photographs—of a farm laborer in California, of a funeral carriage in the San Joaquin Valley, and of an impoverished Black child working on a farm—and suddenly there are letters everywhere: an O in the steering wheel of a car, a lowercase a made by the ornate metal curving around an oval window, an n in the crook of fingers clutching a hat, a Y in the arms and hoe of the child alone in a field. One almost wonders if the pictures could be arranged like an alphabet or aligned to spell out a message: W h O? a n Y.

Lange is famous for not only her portraits but also the captions she wrote for most of them. She was intent on providing details about her subjects—their location and date, plus snippets of conversation that convey a person’s idiosyncratic speech. (A glaring exception is Lange’s most famous photograph, Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, for which Lange provided no caption; its subject, Florence Owens Thompson, a woman of Cherokee descent, was not identified until 1978.) Though her captions were not used in the official publication of her government-commissioned photographs (over which she retained no artistic control), Lange continued to write them throughout her life. Pictures and words conjoined. Details and order, as if she could forestall the disintegration all around her by elegant framing and tidy notes.

Even in scenes of mind-numbing, backbreaking agricultural work, order nonetheless prevails—light and dark, lines and angles, rhythm and repetition. Lange famously insisted on showing the beauty of her subjects, their dignity and resilience. She thought it disrespectful, demoralizing, and cheap to photograph filth or despair. Instead, she seemed to view the world around her arranged in a parade of compelling shapes. It’s not hard to imagine Lange stopping her car to capture a group of men squatting in the dirt, their bodies folded in matching scale, making a compelling line of o’s between the vertical l’s of the porch beams.

Hard and soft. That might be one way to describe Lange and her pictures. She was known for being uncompromising, tenacious, and sometimes harsh (both professionally and—especially—in her private life as a mother). Her photographs are hard in their formalist adherence to structure as well as to shape and line. But they’re also soft in their sensibility for shadow, for the human expression conveyed by a hand or a posture, for her slightly blurred horizons and infinite midrange grays.

Horizon lines often cut across Lange’s photographs at an extreme—either higher or lower, flatter or more pitched, than one might expect. This gives the impression that the photographer could have been standing up high, pointing a camera sharply down on a scene (as in the pictures of farm workers in the fields) or lying flat on the ground aiming the camera up (as in the close-up faces and pictures of people in their cars). Either way, Lange seems to occupy a contorted, unnatural position relative to her subjects. Rarely is she at eye level. Instead, she becomes a bit of the landscape or natural world in which her subjects seem to live.

Many of Lange’s subjects are either working or not working. People plow and hoe fields, pick cotton, weigh peas, churn butter, nurse babies. They also squat in the dirt, lean against cars or buildings, stare into space. Machines, when they appear, mostly convey unreliability.

In Migratory Pea Pickers, Nipomo, California, a car with a couple seated on the running board, packed to the hilt, is not moving. Its front wheel seems off-kilter as it dips out of the frame. The windows, two squares and two rectangles, are covered with fabric and newspaper, or are blocked by belongings. When you notice that the roof of the car is hoisted partway in the air with old two-by-fours, you realize that they must be living here, in this makeshift vehicle (is it even a car?), dressed in their Sunday clothes as if sitting on a front porch in the middle of nowhere, the man’s mouth (mirroring his glasses, vest buttons, and the little circle formed by his thumb and pointer finger) pinched in a tight o.

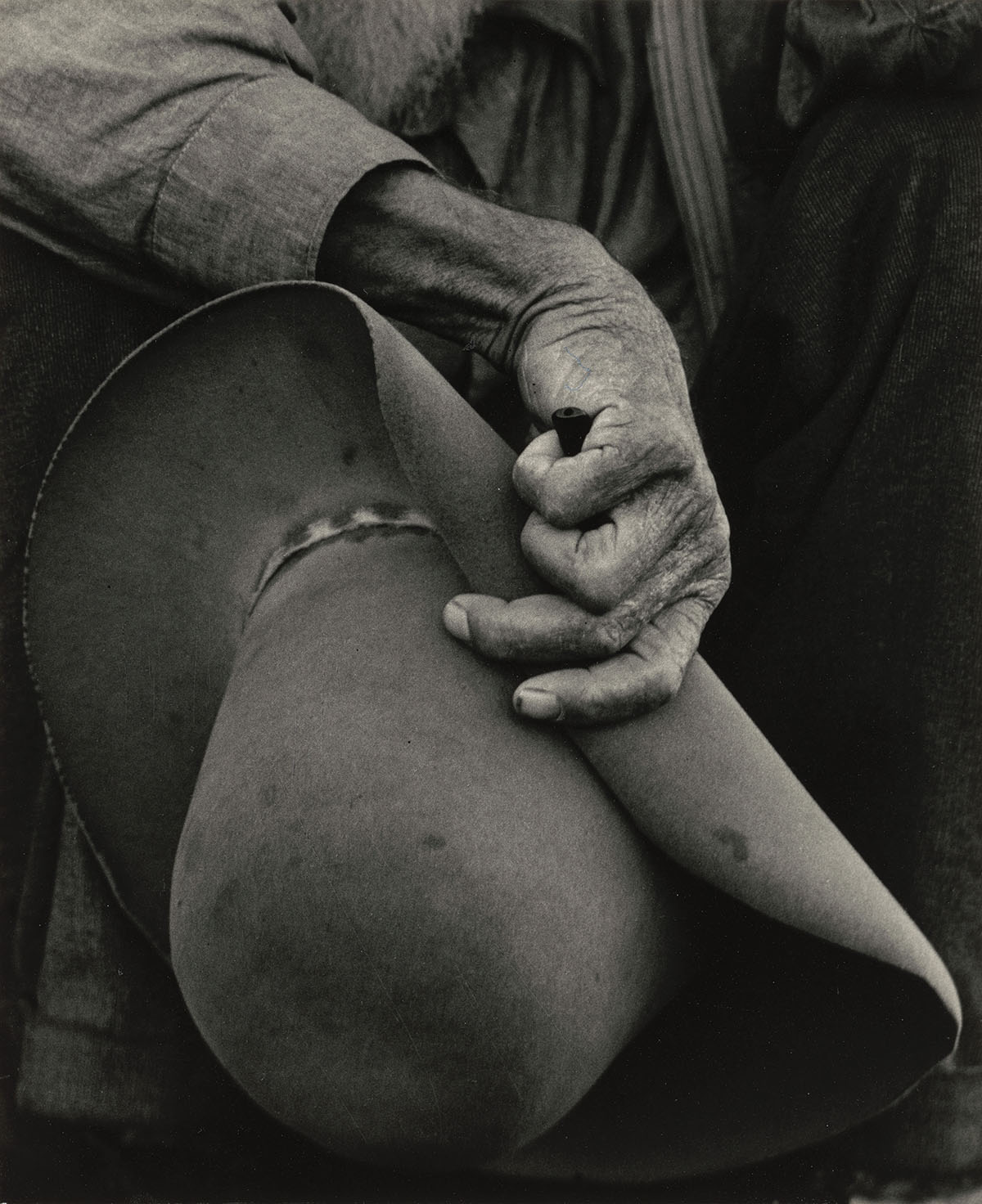

This is the kind of dominant image of the Great Depression that we have inherited from Lange and her contemporaries—images famous for their “realism” as well as their romance and nostalgia. People forced to find new ways of working when work dries up. People forced to move or keep moving when fields dry up. Women forced to keep things reasonably clean in the midst of squalor. Lange documented human resourcefulness in wretched conditions, but also the exhaustion of so much idleness, waiting, hoping, and hungering. We see it in the delicately curled fingers of a man’s weathered hand, which grasps both a thin black cylinder (perhaps the end of a pipe) and a dirty hat. This man may have lost everything, but he still adheres to basic rules of decorum: he knows when it’s right to remove your hat.

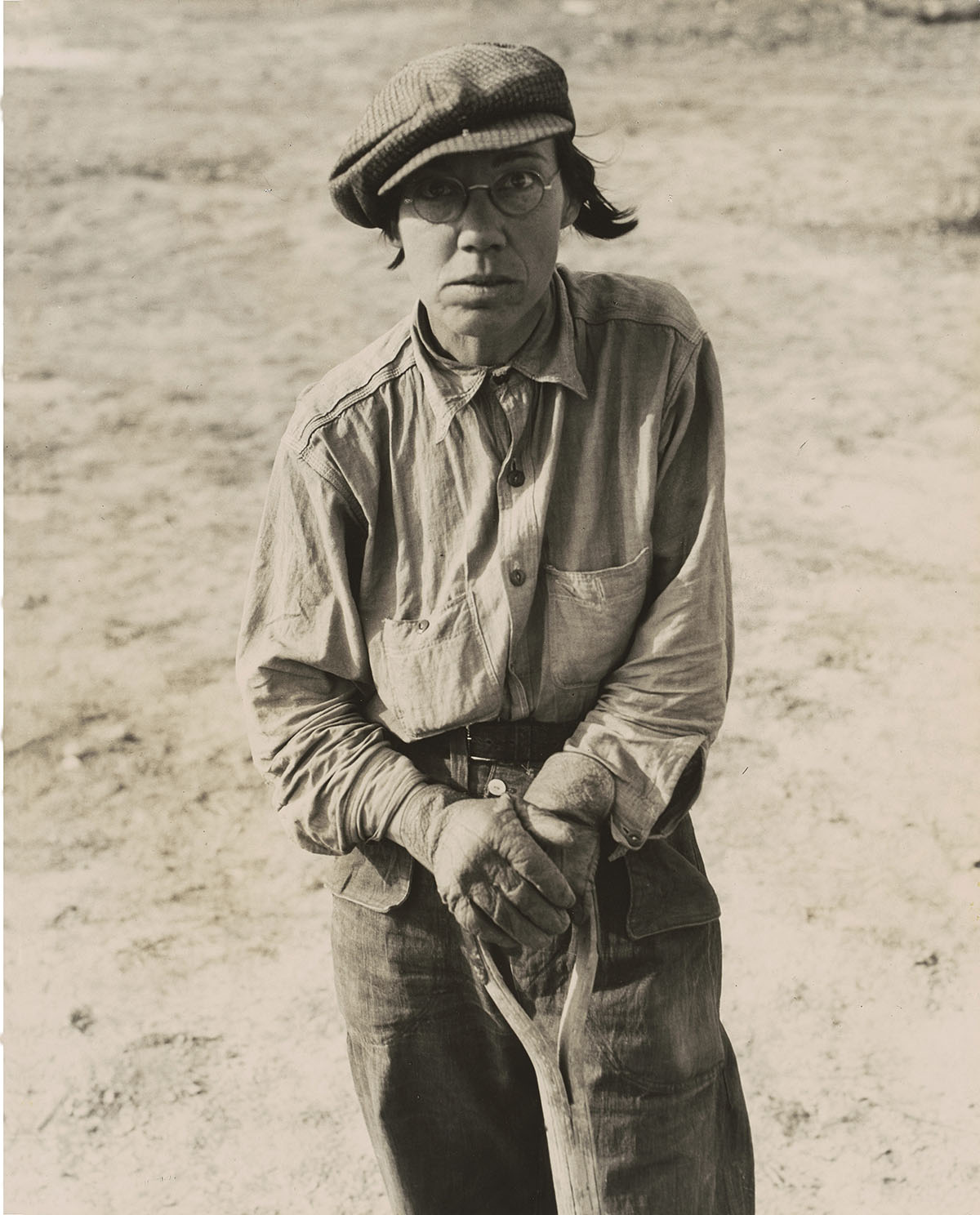

Lange must have had a special fascination with hats—alongside her interest in hands and feet. It’s amazing how much a hat can convey, whether cocked to one side, pulled down tight over the whole face, or sitting squarely. A hat offers utilitarian protection against the sun, wind, rain, or cold. But a hat can also suggest status. It can denote culture or nationality. It can be camouflage, cover, or a way of blending in. In Lange’s pictures, it can also confuse or obscure race, a quality she may have relied on in photographing field workers of various ethnicities and races across the West and hoping that, back in Washington, D.C., her pictures of nonwhite migrant laborers might slip through for publication—despite the explicit effort of the FSA to document and highlight white American suffering.

In a strange premonition of Andy Warhol, all of Lange’s subjects become stars in her portraits. It can make you uneasy to stare at them in their undone beauty. Their lives so harsh. The photographs so fair. There’s no way out of the bind, and Lange implicates her viewers in the problem.

In a 1942 photograph taken at the Weill Public School in San Francisco, a little Japanese-American girl pledges allegiance to the flag with her hand splayed across her plaid coat, her expression serious and strained. She didn’t ask for it, but in the photograph, she becomes the face of FDR’s Executive Order 9066, which, beginning in 1942, incarcerated people of Japanese descent in internment camps. The War Relocation Authority hired Lange to document the camps, though she was prohibited from photographing armed guards, razor wire, or other markers of violence, and her photographs remained largely unknown until 2006.

Looking at Lange’s photographs in 2023, we know, of course, more than she did when taking them. We know the last Japanese internment camp closed in July 1946. We know the FSA failed in its mission to alleviate rural poverty or resist the corrosive effects of industrialized farming. We know migrant farm workers continue to pour into the United States to work in dangerous conditions with few, if any, protections. We know the air is changing for the worse. Yet something about the pictures keeps projecting hope. Human hands, tattered dresses, wheels, hats. An ambiguous new alphabet.

What is a face? What are we facing? These questions, raised by Lange’s photographs, continue to resonate today. The problems are basic, perennial. What is it like to live in a world that has left you behind? What does it mean to work? To be a child? To hope? Lange’s subjects have been pushed to the extremity of social and environmental conditions. The pictures direct us to look. Look at the skies and the shapes and the strange order of disorder. Look at how ordinary everything seems to be even as it is falling apart. Look at how still the world appears in its perpetual motion (the cars stalled, the air thick, the eyes unblinking). Look at repetition. Look at a woman looking.

Women looking. It’s an inversion of the long-standing subject position for women and girls—who are supposed to be seen (and not heard), looked at. Lange looked. Her work is remarkable just for that. The deadpan focus of a woman making a decision, making a frame. There’s a subtle but persistent heroism in the female figures she photographed. They seem thoughtful, tough, alert. The men, by contrast, appear tired or manic—almost wild. They’re losing it. Gripping their hats, crouched near the ground, worn down by labor and time.

Here is a touching fact about Lange. Late in her life, she taught photography courses and gave her students the assignment to photograph “where they live.” When one of her classes challenged her to do the same, she brought in a photograph of her own bare foot, twisted from childhood polio. In the same course, Lange assigned poetry and literature. She taught Wallace Stevens’s poem “Theory,” which begins: “I am what is around me. // Women understand this.”

Understanding cuts both ways. The order, the beauty, the grace. The filth, the depravity, the despair. It’s so easy to lose your place—to find yourself suddenly amid things you never expected, never planned. The razor-thin edge between one state and another. Lange’s pictures keep us balanced on that rim, looking at the repetitions we’re entangled in, facing what is around us.

It’s all connected: the past, the present, the future, the Great Depression, the cutting of native grasses across the Midwest that left the soil loose and exposed (a million acres of grass destroyed every year between 1923 and 1930), the tractoring of dirt, the damming of rivers and stealing of lands, the displacement of peoples, slavery, illness, internment, wars, drought, loss of homes, loss of jobs, loss of dignity, resilience, love, invention, cars, dreams, ideals, art, politics, collapse, revival, work, rest, boredom, hunger. It’s all connected. A woman taking pictures and a woman writing at her desk. The Dust Bowl and the opaque air streaming down from fires a thousand miles away. I can almost feel the heat, nearly hear the roar.

The exhibition Dorothea Lange: Seeing People will be on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., from November 5, 2023, through March 31, 2024.