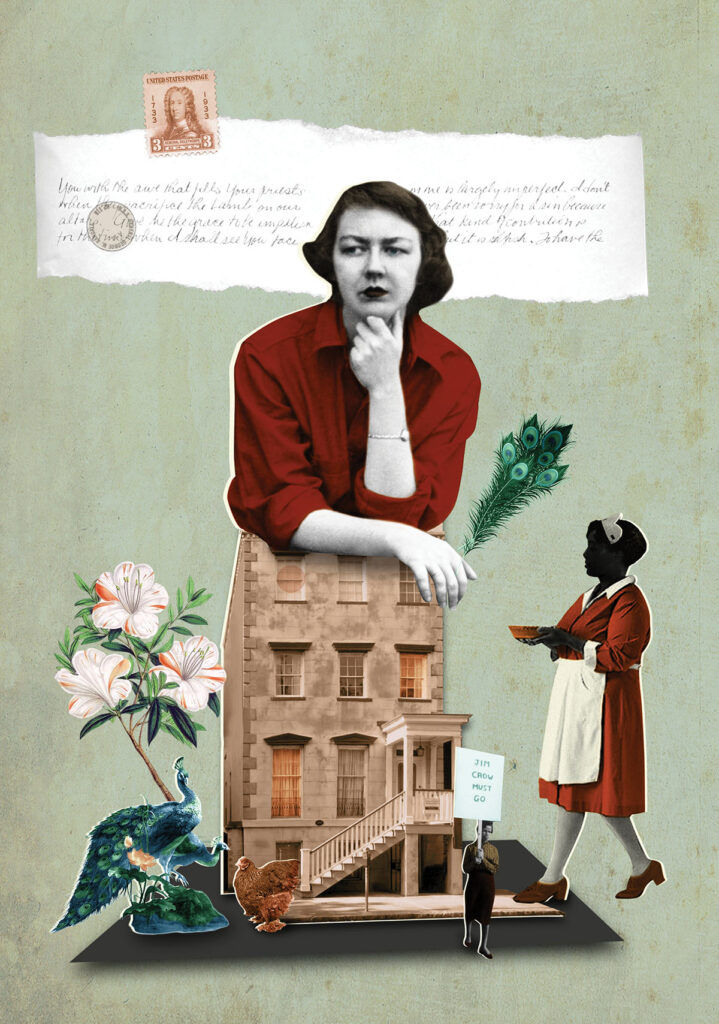

Origin Stories

What we know of Flannery O’Connor’s childhood—and how her views on race took shape—is incomplete if her caretaker Emma Jackson remains in obscurity

For more than two years, I have lived in the lower level of Flannery O’Connor’s childhood home, which sits on a quiet residential block in downtown Savannah, Georgia. I had studied O’Connor’s life and work in graduate school, and it was my research that enabled me to recognize the gray façade of the author’s first residence during a routine Zillow search. This happened one morning in late September 2020, at the height of the pandemic. I was subletting an apartment in Savannah, spending my days scrolling through the same stock of dismal, overpriced rentals. Spotting the listing for the garden apartment on Lafayette Square, I imagined fate at play. A week later, I signed the lease.

Because the house functions as a museum devoted to her youth, I am continually reminded of O’Connor. Outside my front door stands an iron placard dating her time in the house (1925–1938) and detailing her major literary accomplishments (three O. Henry Awards and a posthumous National Book Award for her collected short stories). Occasionally, her admirers peer into my windows or ring my doorbell, mistakenly believing that the entrance to my apartment is the starting point for the weekend tours that run through the rest of the house. When they catch me coming or going, they ask questions that I have trouble answering succinctly, given my extensive knowledge of the writer. On the days when I encounter none of her fans directly, I hear the amplified voices of trolley-tour drivers saying her name as they wheel around Lafayette Square, which is also home to the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, where O’Connor was baptized and received her first communion. Once, I opened my mailbox to find junk mail addressed to Mr. Flannery O’Connor.

The narrow, three-story house was built in 1856. For the next century, the space I now rent was a dirt basement. Prior to Savannah’s liberation by General William T. Sherman’s troops in December 1864, the basement may have functioned as living quarters for enslaved people. A brick fireplace, sealed long ago, offers the only tangible clue to this history, though research indicates that enslaved people did reside in the lower levels of many Savannah townhouses. Newlyweds Edward and Regina O’Connor purchased the house in 1923, and in 1925, their only child, Flannery, was born. Though the family left Savannah in 1938, briefly staying in Atlanta before settling in the middle-Georgia town of Milledgeville, the house stayed under the ownership of a moneyed cousin, Katie Semmes, who lived next door and who helped the O’Connors financially. Upon her death in 1958, Semmes gave the house to the 33-year-old author, who opted to seize its investment potential and turn its floors into rental units. This is when my apartment came into being.

Real estate was not a foreign venture for O’Connor. Her father had worked in the business until his premature death from lupus (the same disease that afflicted her), and her mother began managing rental properties a short time later, likely out of financial necessity. I have read enough of O’Connor’s letters—published and unpublished—to determine that she probably deferred to her mother in matters of renovating and managing the rental units in her childhood home. Her lupus, diagnosed when she was 25, had progressed considerably by the late 1950s, relegating her to crutches. She devoted her limited store of energy to her fiction, her correspondence with friends, and her Catholic faith. Even so, when I stand amid the gold-flecked laminate countertops and retro cabinetry of my kitchen, I sometimes wonder which of the O’Connor women approved its design.

Mine is the only rental unit remaining from the home’s three-decade stint as an apartment building. In the early 1990s, the Flannery O’Connor Home Foundation, focused on preserving the writer’s legacy in Savannah, restored the residence to its Depression-era state, re-creating paint colors and room configurations that a young Flannery would have recognized and opening the Flannery O’Connor Childhood Home Museum. The basement was retained as an apartment to provide the foundation with an additional source of income. Because the low-level unit has its own street entrance, tenants could come and go quietly, without intruding into the museum’s affairs. According to Hugh Brown, the Armstrong State College professor who initiated the fundraising campaign to buy the house and establish it as a literary landmark, the apartment also held the least historical value to the foundation’s mission. “In the O’Connor days,” he wrote, “the basement was used for storage.”

The outdoor area at the rear of the house was a different matter. During O’Connor’s childhood, the walled space was part garden and part chicken yard. There was also a playhouse where Mary Flannery, as she was then called, is said to have convened audiences, entertained friends, and read her earliest stories aloud. Biographers and scholars have taken care to preserve the memory of this playhouse. Relying on recollections supplied by O’Connor’s childhood playmates, the biographer Brad Gooch has described the structure as “gazebo-like” and “fitted into a corner of the back yard.” But this story is incomplete. Narrative accounts of the rear exterior of the O’Connor home omit the existence of a small brick dependency, a single-story carriage house that edged the southern property line. Records preserved by the Georgia Historical Society, in downtown Savannah, indicate that this structure was built prior to 1888 and existed through at least 1955—and that for a portion of O’Connor’s early youth, this dwelling was occupied by a woman named Emma Jackson.

According to public records, Jackson was a domestic worker who was in her mid- to late-50s when she began her employment with the O’Connor family. She is listed as “nurse” and “maid” in the 1930 U.S. census and Savannah city directory, respectively, indicating that both childcare and housework fell among her duties. As a Black woman in the segregated South, she likely filled these roles for a meager weekly or monthly wage, a sum devised to strip any agency a domestic employee like Jackson might have had over the number of hours she worked each day. Such arrangements were not unusual at the time. By 1935 (the year Flannery O’Connor turned 10), 60 percent of urban, white southern families living above the poverty line employed at least one full-time domestic worker, and that position was typically held by a Black woman. That same year, the Social Security Act—its passage notably influenced by southern politicians—codified the exploitation of domestic laborers, as well as agricultural workers, by excluding them from the economic protections it promised. This led to the intended effect of barring Black southerners from achieving basic financial security—and intergenerational wealth—while granting many southern whites the possibility of increased class mobility. The implication of this history is that when Jackson was employed by the O’Connors and living on their property, she was most likely underpaid, overworked, and without many alternatives.

Biographical accounts of O’Connor’s childhood fail to include Jackson’s role with the family. Visitors to the Flannery O’Connor Childhood Home do not learn her name. Until 2022, when the scholar Patricia Ann West became the first to surface records pertaining to Jackson’s employment with the O’Connors, scholarly interpretations of the author’s early proximity to Black servitude relied on supposition. Even now, many of the facts of Jackson’s life and her tenure as O’Connor’s caretaker remain unknown. Part of the problem has to do with records pertaining to Jackson’s presence and influence—poorly documented to begin with and unavailable for public discovery until the 2000s. Adhering to the 72-year rule, the National Archives did not release 1930 census records until 2002. Meanwhile, the only publicly available record of Jackson’s tenancy in the O’Connor home was in the hardbound tomes of the Savannah city directory; its separate listings for white and Black residents made it even more difficult to link Jackson with the O’Connor household. These circumstances, combined with the scattered and privately controlled nature of materials related to O’Connor’s life, meant that biographical study of the author was, for many years, limited to a carefully curated selection of the author’s letters and the recollections of her friends, family members, and colleagues. Which is another way of saying that white identities—the author’s and those of her editors and other close relations—have played a crucial role in shaping the popular narratives around O’Connor’s lived experience.

In 2014, Emory University acquired O’Connor’s private papers, blowing open the world of O’Connor scholarship and democratizing access to several documents referencing Jackson and her relationship to the family. That West is the only researcher to have included her in conversations about the author’s childhood—and so recently as 2022—is a testament to the vastness of the archive and its fragmentary store of material related to Jackson.

Whether or not O’Connor should be revered for her fictional portrayals of racism in the Jim Crow South has long been a point of contention among both scholars and readers. Some early critics of her work argued that her renderings of Black characters were ill-defined caricatures. Others applauded her emphasis on the moral failures of white southerners. Not until the 1979 publication of The Habit of Being, a collection of the author’s private letters, did the conversation about O’Connor’s fictional renderings of southern race relations shift to include her personal stance on the issue. The book, which was edited by O’Connor’s longtime friend Sally Fitzgerald, preserves the author’s casual use of the N-word, her routine jokes about the Black laborers on her mother’s farm, and, famously, her refusal to entertain the idea of welcoming James Baldwin into the living room of her rural Georgia home: “In New York it would be nice to meet him,” she wrote to her friend Maryat Lee, “here it would not. I observe the traditions of the society I feed on—it’s only fair.” But for all the incriminating evidence that The Habit of Being introduces, the book represents only a portion of O’Connor’s writing on race and integration. Notably, it omits a substantial number of letters she wrote during her teens and early 20s, many of which became publicly accessible through the Emory archive. In 2022, a selection of these was finally published in Dear Regina: Flannery O’Connor’s Letters from Iowa, though many others remain discoverable only through in-person visits to Emory’s Rose Library. (O’Connor’s literary estate rarely affords publication rights from this store of material, which means that scholarly discussions about much of the author’s early correspondence relies on summation.)

In trying to reconcile the conflict between O’Connor’s racism and the moral aims of her fiction, most scholars argue that the writer was largely a product of her time and place. But only a few have explored the ways in which Savannah’s racial and class divides shaped those early years—despite the availability of new documents related to O’Connor’s youth. Instead, they focus on O’Connor’s adult response to the civil rights movement. During the early 1960s, she penned some of her most vitriolic commentary on race and integration in letters to friends, including this declaration, made in the last year of her life: “You know, I’m an integrationist by principle & a segregationist by taste anyway.” This statement was published for the first time in 2020 in Angela Alaimo O’Donnell’s Radical Ambivalence: Race in Flannery O’Connor. And yet, other archival documents show that O’Connor’s deepest feelings on race in America were formed long before the spring and summer of 1963—long before the Birmingham uprising, the assassination of Medgar Evers, and the March on Washington. Indeed, O’Connor revealed her thoughts on integration as far back as the early 1940s, when she was a teenager visiting New York City. Writing to her mother, she remarked that after using the integrated restrooms, she might be in need of a physician’s assessment.

It has long been part of the O’Connor story to link the precocious creativity of her youth to the kind of woman and artist she became. This is why tourists visit the childhood home: to be regaled with tales about the author’s first habits and affections, to trace the evolution of her talent and persona, to find Flannery O’Connor in the world of Mary Flannery. In this context, it is disingenuous to overlook the forces that shaped her racial thinking during those formative years—and to ignore the part that Emma Jackson may have played in this story.

Along the western exterior wall of my neighbors’ two-story garage, I can see what looks like the faint outline of the carriage house that once stood in the O’Connors’ back yard. This is all that remains of Emma Jackson’s home. By the time the Flannery O’Connor Home Foundation was determining what to do with this space, there was no carriage house to consider refurbishing, no chicken coop to populate with new birds, no wooden playhouse to exhibit. Hugh Brown (of Armstrong State) had expressed a desire to re-create the playhouse, but the idea was scrapped in favor of a traditional Savannah garden, which is lush with shades of green and manicured to spotlight a small stone statue of Saint Francis.

The foundation does not employ a regular groundskeeper, so in my short time in residence, I have tended this garden. I have lined its circular pathway with river rocks, trimmed its overgrowth, cleared it of fallen leaves and the occasional limb dropped by an ancient dogwood tree—the only flowering thing on the grounds that dates to the author’s youth. I have filled bare patches of soil with jonquil bulbs and aucuba harvested from my grandmother’s yard. In empty pots, I have planted oleander and dipladenia. This outdoor refuge was created in honor of the author—the “Flannery O’Connor Garden,” reads a plaque that was buried by leafy ground cover when I first moved in—but when I am yanking weeds from the root-laced earth or cutting back the jasmine that wends along the southern wall, I like to imagine that this small patch of land belongs to me. Because the garden is not open to visitors, because it bears little resemblance to the back yard O’Connor knew, I think of the place as more private sanctuary than relic of the author’s youth. Though it is that, too.

Here is the story you are most likely to hear about this back yard: it was where O’Connor learned to raise chickens and where she realized her affection for them. (Her passion for fowl would culminate in her collecting at least 40 peacocks, which roamed the grounds of Andalusia Farm in Milledgeville, where she lived for most of her life.) One of those chickens, a buff Cochin bantam, famously had the ability to walk backward. In 1931, when the author was six years old, Cousin Katie Semmes recruited Pathé News, a British producer of documentaries and newsreels, to visit Savannah and film the bird performing its trick. You can still see the short film, the bird walking forward and backward, at one point appearing beneath what looks like the wooden staircase that once led to the main house. The staircase that exists now is metal and rusting, and the space underneath would be no good for showing off animal tricks, occupied as it is by an air conditioning unit.

It has been erroneously reported that the talented chicken was of the frizzle variety, so named because its cowlicked feathers give it the appearance of having received an electric shock. Sally Fitzgerald seems to have initiated this fallacy in an endnote to the Library of America’s Collected Works, which she edited. Possibly Fitzgerald was perpetuating a myth that O’Connor had conjured on her own. Or maybe the author’s mother had recalled the story to Fitzgerald this way. In any case, the video evidence proves otherwise. The chicken’s feathers are smooth, gleaming in the sunshine that young Flannery squints toward as she holds the squirming bird. And yet, I have come to believe that whoever first mischaracterized the chicken in question was capturing an essential truth of O’Connor’s history.

In the summer of 2018, I found myself in the manuscript library at Emory, the last and longest stop on a journey that had taken me all over Georgia, to various sites associated with the author. I was in the second year of my MFA program and had persuaded one of my professors, a biographer, to oversee my work as an independent study, the focus of which had begun to muddy and shift amid mountains of material. By the time I reached the primary archive, I had opened my research to anything, everything.

One day, I came across an early and unpublished manuscript titled “Frizzly Chicken,” a story that captures a sliver of Emma Jackson. In the piece, written from the perspective of the author as a child, O’Connor describes Emma as both playmate and nanny, the person who turns spoonfuls of grits into flying birds and, in later years, chaperones after-school adventures. One such adventure involves searching for a frizzle chicken. The two of them go looking every afternoon, usually at the home of Emma’s friend Belle Williames. O’Connor loves these visits and writes of the home’s wooden windows and the cracks in the floorboards that afford her a view of chickens nesting below. This is the kind of existence she desires for herself.

Soon, though, O’Connor’s hunt for a frizzle chicken ends. After she drinks some water from a well on Williames’s property, her mother chastises her, forbids her to return, and drags her to the doctor, who gives her a shot. Her mother tells her that she has begun to speak and behave like Emma and Belle and that she is too old now to be spending so much time with Black women.

Here, the piece becomes a child’s reflection on her newfound understanding of a racialized world. It is because of the Civil War, O’Connor says, that she can’t visit Belle anymore. She writes of being called a Yankee by an aunt after expressing her preference for eating in the kitchen with Emma. And she writes of her mother’s explanation for why the races don’t socialize in the South. Though she bemoans the loss of her afternoon chicken hunts with Emma, she concludes the piece by accepting her new reality and vowing to keep her place inside it.

“Frizzly Chicken” is a dark and devastating story of how whiteness establishes a dominant place in a child’s mind. And yet, it is as linguistically innocent as it is psychologically defining—an oddly pure articulation of the racism and racial intimacy that long characterized the South. The piece is undated, but it is filed alongside a series of high school and college assignments as well as several short stories written during O’Connor’s time at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop (1945–1947). She would have been reading Eudora Welty by then. It is not unreasonable to imagine that the eight-page piece was her own exercise in the kind of first-person characterization and voice Welty made famous in her 1941 collection, A Curtain of Green. And yet, “Frizzly Chicken” is distinctly autobiographical, referencing not only Emma but also the family members who populated O’Connor’s youth—her veteran father and overprotective mother; her Milledgeville aunts, Katie and Mary, who irritated each other for sport; her aunt Margaret Hynes, who lived with Katie Semmes in the house next door. In this sense, the piece resembles the juvenilia collected in O’Connor’s archives and celebrated by her biographers—the clever critiques of her “Relitives,” for example, that her encouraging father often helped her type.

When I first read the story, I felt certain that it contained more fact than fiction. By that stage in my research, I had encountered the name Emma in other archival documents, in references that mirrored what O’Connor had written in “Frizzly Chicken.” The first of these appeared early in my review of the Emory materials, while I was immersed in Sally Fitzgerald’s notes. In the 1980s, Regina O’Connor authorized Fitzgerald to write a biography (never published) of her daughter and granted countless interviews. In one of these, documented by Fitzgerald on an index card, Regina discussed a servant named Emma who had cared for Flannery in her youth, even accompanying the O’Connors for a portion of their short stay in Atlanta, just before the family’s permanent move to Milledgeville. The recorded memory is brief. While Regina was undergoing a mastectomy, she sent Flannery to stay with her sisters in Milledgeville, where the girl was tended to by Emma. Regina instructed Emma not to allow Flannery to drink from a local spring and not to take her along when she visited with friends. Emma, Regina told Fitzgerald, did both. Fitzgerald recorded the memory without further remark—a departure from her custom of interpreting most everything Regina said—though it seemed clear to me that the anecdote had been told with a kind of bitter humor, with Emma the incorrigible servant at the butt of a white woman’s joke. I photographed the notecard, front and back, as was my habit, and moved on.

Days later, I came across the name again, this time while reading O’Connor’s letters to her mother. In one of these, sent from Iowa City in the spring of 1947, O’Connor wished her mother well on a trip to visit Cousin Katie in Savannah. She wrote, “Hope you get to see Loretta—also Emma. I would like to hear how Emma is—or if Emma is.” Reading this letter only solidified the question that had been forming in my mind: Who was this Emma who had cared for the author in her youth? “Frizzly Chicken” provided no clear answer—it is much less evocative of the woman than of the environment she navigated.

It is tempting to call “Frizzly Chicken” an essay, resonant as it is with Regina’s memories of similar events. But I am wary of such speculation and not blind to the blurring of time and place that appears to occur in the piece. O’Connor’s reference to Aunt Margaret, for example, implies that the woman has died. In actuality, Margaret Hynes died shortly after O’Connor’s 18th birthday, long after the era documented in the piece. Such incongruities have led me to consider “Frizzly Chicken” an autobiographical short story. More than her published work—though that, too, captures shades of O’Connor’s lived experience—the story is rooted in reality, littered with verifiable facts. And it is an origin story, as foretelling of the adult O’Connor as the sweeter, more palatable tales that make up her juvenile narratives.

People seem to know certain things about O’Connor, whether or not they have read her work. She was funny. She collected peacocks. She loved to write about “freaks.” Sometimes they know these things before they learn that she was Catholic. Her fiction is bold, never quiet. It leaves impressions on college students forced to read from anthologies. “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” is the most common entry point to her canon of two novels and 31 short stories, and, despite what some seasoned scholars have told me, I don’t think it is a bad place to start. The story centers on a God-fearing, out-of-touch woman—my favorite of O’Connor’s archetypes—who has been loosed from the security of her home environment. It’s an enticing premise, and O’Connor’s great themes of sin and redemption, of race and class in the segregated South, show themselves variously and memorably.

The story goes like this: The woman, a grandmother, is accompanying her son and his family on a road trip to Florida, and an escaped criminal known as the Misfit is heading in the same direction. The family takes a detour at the grandmother’s request to look for an antebellum home she once admired. (Old white ladies hunting for vestiges of a bygone era are standard O’Connor fare.) But the search is fruitless because the house, the grandmother suddenly remembers, stood in Tennessee and not in Georgia. Her son crashes the car (also the fault of the grandmother), at which point the Misfit and his gang come upon the family and execute each of its members. He saves the grandmother for last, allowing her a moment of clarity—grace, O’Connor called it. After the grandmother is dead, the Misfit tells his criminal companions, “She would of been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

The South that O’Connor conjures in this story—its willfully ungrammatical dialect, its “Christ-haunted” ethos—is somewhat exaggerated for effect, but it is immediately recognizable. Orienting her readers in a concrete realm was, she believed, necessary to their understanding of her mystical themes. “When the physical fact is separated from the spiritual reality,” she wrote, “the dissolution of belief is eventually inevitable.” O’Connor’s idiom is bound to the Bible Belt—the Protestant South and all its social peculiarities as she observed them—but her ultimate concern is injecting this world, often violently, with a supernatural and decidedly Catholic attitude. This approach yields stories in which a child of late-night revelers baptizes himself by drowning in a muddy river, a woman is gored by a divine bull, and a traveling Bible salesman steals the wooden leg of an atheist farm girl.

My affection for O’Connor’s fiction began with her first novel, Wise Blood (1952), but it was her stories that made me a fan. When I first read them, toward the end of my 20s, I was stunned by their strangeness, by their wit and force and commitment to their own mystery. An O’Connor story, I realized, does not work to make itself understood. Occasionally, this meant that I, a person who wanted very badly to arrive at solid interpretations, felt stupid. But whatever difficulties I encountered in meaning were overshadowed by the thrill of discovering O’Connor’s characters. In all their eccentricities and primitive preoccupations, these people seemed plucked from her own milieu, and yet they were familiar to me, a southerner two generations removed. They took the shape of my paternal grandmother, who was so concerned with the manners of others that she seldom remembered her own, and the decorator in my hometown who, to spite his neighbors, cleared his front lawn of grass and replaced it with dirt mounds of bulwark proportions: never mind his own view when he could make theirs a little uglier. O’Connor’s characters were emphatically unlikable, possessing more pride than self-awareness, always stubbornly devoted to their own wrongheadedness. But I loved reading about them, particularly the women, who embodied a world untouched by moonlight and magnolias, who gossiped and abused and thumped their Bibles across the page like hardened anti-Scarletts. In these women, I saw O’Connor deconstructing conventional notions of gender. I saw her transforming the identity of whiteness—so prized in her society, so relentlessly reinforced by various systems—into an assortment of moral and spiritual failures. But I did not have to squint to see, alternatively, a southern writer too fluent in native ideologies to have escaped them.

I understand now that my expedition into O’Connor’s life and letters, my journey around Georgia in the summer of 2018, emerged from this recognition. My connection with the author and her work had intensified to the point that deeper questioning was necessary. This is what my independent study became: an interrogation into the facts of O’Connor’s worldview, into the realm of scholarship that seeks to explain (or explain away) that worldview, into the privileges that tend to facilitate the bonds between problematic artists and their fans. My relationship with the woman and her stories had been buoyed by what I believed we had in common—chronic illness and an interest in the inanities and complexities of southern manners, among other things. What did it mean to love, admire, identify with these parts of O’Connor’s work and persona without taking stock of the rest?

At the conclusion of my independent study, I submitted my obligatory essay, which documented my trek into all the questions I had resisted asking as a devoted reader of O’Connor’s fiction. In that piece, I wrote about my own southern upbringing. I wrote about how certain comportments and characters from my life appeared in O’Connor’s stories, how that had made me feel seen but not implicated in the problems of my society, how I had been missing the point. I wrote, too, about the fallible notion that art equals atonement, which is a mainstay in discussions—mostly among white scholars—of O’Connor’s racism. And I wrote about Emma, about “Frizzly Chicken,” and the truth that I believed the story revealed about the mundane origins of the author’s most profound failure. I earned an A for my work, a result that struck me as incongruous with the most personal of excavations, the kind of interpreting and reinterpreting that never finishes, or ought not to.

After I had moved into the basement apartment of O’Connor’s childhood home, after I had scrubbed years of mud from its lowest-lying windows and pruned the Asiatic jasmine that covered too much of the ground, after I had begun to feel at home, I continued to think about Emma. In my summer of steady research, I had not been able to determine her last name. That she had ever lived on the O’Connor property had not yet occurred to me, so I did not search the 1930 census—the only year that captured Flannery, then five years old, as a resident of Savannah. Instead I combed journal articles and biographies for references to Emma, hoping to verify her identity and relationship to O’Connor’s childhood with harder proof than what I had found in the archives. Patricia Ann West’s paper was not yet published, and my searching was going nowhere.

One of my mentors, a fiction writer, tells me that certain subjects grab hold of a writer and refuse to let go. I was sitting on my sofa one afternoon, doing nothing on the Internet, mentally scolding myself for wasting time, when I finally got the idea that had been eluding me. I paid for a subscription to Ancestry.com and began searching census records for the O’Connor family. That’s where I found her: Emma Jackson, 58 years old in 1930, born in Georgia to Georgia-born parents. She is listed as single but might have been widowed. She never attended school and could not read or write. When I followed these facts to the Georgia Historical Society, I copied her listing in the city directory: “Jackson, Emma, maid Mrs. E.F. O’Connor, r, 207 Charlton.” I asked the person at the front desk what r meant. “Rear,” she told me, transforming what I knew of the house’s back yard. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps from 1888 through 1954 said more about the scale and construction of the carriage house, and when I returned home and stepped into the garden, I found what I guessed to be its shape marked on my neighbors’ two-story garage. This is all the evidence that remains of Jackson’s life at O’Connor’s childhood home—the faint outline of a small, single-story building that, at certain hours of the day, is hidden by shadows.

Those who influence and populate a famous life are often stripped of their own narratives, understood only in terms of their proximity to the subject deemed worthy of interest. That fact becomes an injustice when the person’s lived experience is also one of subordination. In 1930, the U.S. government, the City of Savannah, and the O’Connor family defined Emma Jackson by her subjugated status—servant, nurse, maid. In her lightly fictionalized recollection, Flannery O’Connor further debased Jackson’s memory by rendering her as a tool for her own racial (and racist) awakening. In the reminiscences of Regina O’Connor, recorded by Sally Fitzgerald, no effort was taken to preserve Emma’s surname. And in historical accounts of the author’s first residence, Jackson’s carriage house is absent, the space it once occupied reimagined as a childhood idyll. This is how Emma Jackson was erased from Flannery O’Connor’s story. Returning her from obscurity becomes an exercise in parsing untrustworthy or incomplete information—documents preserved by systems of government that cared little about Black lives and enduring stories that were first told through white perspectives. I can tell you the things “Frizzly Chicken” says about Jackson. She was a Baptist. She had a nephew, George, who built the chicken coop that stood in what I’ll call her front yard. Her brother-in-law lived in Alabama. She didn’t chew tobacco. I can’t promise that any of these details are true.

I like to hope that somewhere, maybe in Georgia, maybe even in Savannah, there is a grandchild or great-grandchild or other distant relation of Jackson’s who can recall the woman more fully, who might be willing to revive her history both in the context of the O’Connor family and outside it. I have tried to find such a person. Through public records, I have traced a number of Emma Jacksons and encountered the possibilities of the woman’s life. Probably she was born somewhere in middle Georgia. Probably she connected with the O’Connor family through Regina’s Milledgeville ties. In one version, she is widowed with two children—Joseph and Laila—both grown by the time she relocated to Savannah and to the carriage house. In another, she spent her final years in Florida, caring for her aging aunt. In yet another, her life ends in a Savannah nursing home. If she was never married or never took a man’s last name, her parents may have been Benjamin and Louise or Thomas and Eddie or Green and Ellen. I’ve tried to confirm these details for so long because Emma Jackson should be remembered to students of O’Connor’s biography, to those who visit her childhood home. She should be remembered for who she was beyond the author’s narrow rendering—a difficult task, given the paucity of public information surrounding her. And yet, I believe in memory despite an absence of hard facts. I believe that in all that we do not know of her, Emma Jackson’s story becomes her own.