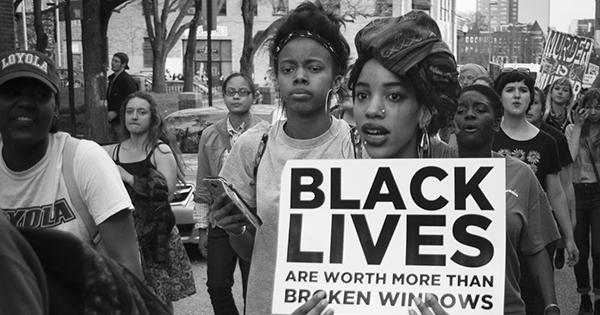

Within days of Freddie Gray’s death on April 19, from injuries he received while in police custody in Baltimore, public historians acted to make sure the event and the several days of protests that followed would not be forgotten. The result was Preserve the Baltimore Uprising, an all-digital collection hosted by the Maryland Historical Society. People have so far submitted almost 2,000 images to the website, capturing not only peaceful demonstrations and police in riot gear but also looted stores and a city on fire. Cofounded by the society and Denise Meringolo, a history professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, the growing archive also includes videos, blog posts, oral histories, and 7,000 City of Baltimore internal emails pertaining to the unrest. Collaborators hope the collection will generate online exhibits and be adopted as a teaching tool.

Joe Tropea, the Maryland Historical Society’s digital projects manager and curator of film and photographs, has helped model Preserve the Baltimore Uprising after other digital memory sites, including those that grew out of similar tensions between African-American citizens and the police in Ferguson, Missouri. Prior to this century, most of what museums preserved came from the wealthiest members of society, Tropea says. “Now we’re at a time where everyone’s walking around with a camera.” In addition to capturing the events sparked by Gray’s death, many of the images submitted to Preserve the Baltimore Uprising reveal neighborhoods that have never before been part of the historical society’s archive.

The six officers charged with Gray’s death go on trial in October. Tropea is preparing for more demonstrations—and likely more material for the collection. “The ability for everyday people to be able to preserve history that they witnessed or participated in,” he says, “to me, that’s the importance of this project.”