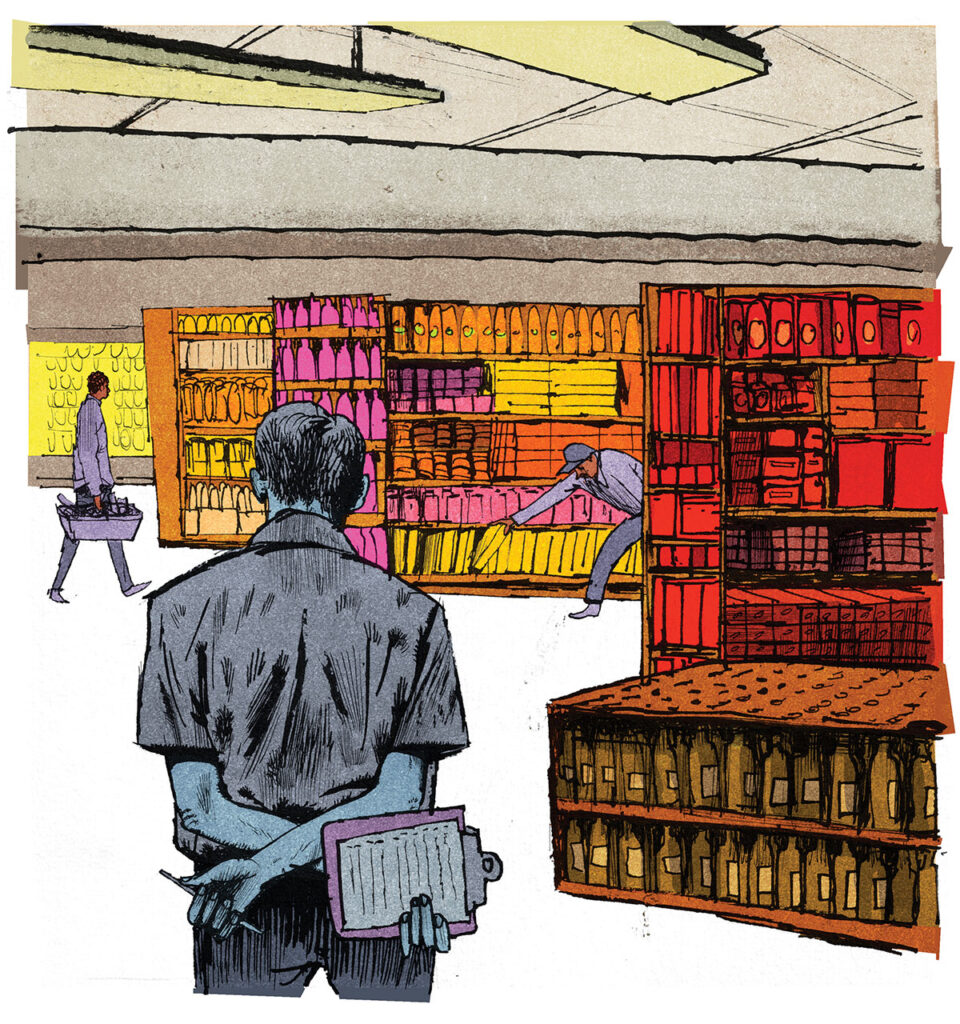

When I was going to college, I worked off and on for several years on the night crew at a Sunflower Food Store in Cleveland, Mississippi. We came in an hour before the store closed and began unloading the trucks that arrived from the company’s warehouse, and we left before the store reopened the next morning. I stocked the baking, grain, and pasta aisle and then, near the end of each shift, spent an hour or so either sweeping and mopping the floors or burning paper and cardboard packaging in the incinerator room, where the temperature often reached 140 degrees. Unlike a lot of guys on the crew, I always assumed the job was temporary, that I would move on to greater endeavors. But I actually came to like the work and developed a sense of pride in it, and I learned a lot—not just about the grocery business—from the manager, an exacting taskmaster named James Williams.

Mr. Williams, who died in 2020 at the age of 82, made it clear at the outset that he would fire you for any one of several transgressions. The first was stealing. If I wanted a Twinkie during our break, he told me the day he hired me, I would have to pay for it; if he found out that I’d filched so much as a 10-cent package of Nabs, he’d let me go without remorse. Once I’d been trained to order stock, another cardinal sin would be to run out of staple items before a holiday. If there was no Duncan Hines Butter Golden on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, customers could buy the Betty Crocker version or even bake a different kind of cake. But if I ran out of, say, cooking oil, he’d put me on notice, and the next time it happened, I’d be looking for other employment. Ditto for over-ordering nonessential items and letting them expire. Last but by no means least: every item on every shelf had to be fronted. He would walk my aisle first thing every morning, and he expected to see two solid walls of readable labels, everything right side up, no visible gaps anywhere. He said he would not tolerate sloppiness, that our customers deserved better.

We weren’t the only grocery store in town. The nearby Kroger was much larger and part of a huge national chain, whereas we were strictly regional. Kroger offered more choices and, if memory serves, even had a bakery and a deli. At first, I assumed that Mr. Williams’s lecture about what our customers deserved merely reflected his desire to keep his own job. But after I worked for him a while, I began to see things in a different light.

Cleveland, at that time a town of around 13,000, is situated in the Mississippi Delta, the poorest region in the South, if not the country. The counties that lie entirely within this broad, flat, agricultural region were and are majority Black. By the ’70s, the schools could no longer remain legally segregated, but throughout much of the Delta, white people had gotten around that by creating all-white private schools—like the one my parents had scraped to send me to in my hometown of Indianola. Cleveland, by virtue of being the site of Delta State University, which I attended for two years before transferring to the University of Mississippi, was a little more open-minded than many towns, and Cleveland High School was at least nominally integrated. But the housing situation was just as bifurcated as in Indianola. Almost all the white people lived west of Highway 61—the famous Blues Highway—and nearly all the Black people lived east of it. The highway ran right past the strip mall where our store stood, making it the closest full-service grocery accessible to the Black community. My impression at the time was that precious few Black people shopped at Kroger, where the prices, I believe, were a little higher. The whites who shopped there seemed more affluent than the people who shopped in our store. Our clientele, Black and white alike, tended to be working class.

One of the big local employers at that time was a Douglas & Lomason plant that manufactured automobile parts. I had worked there for about a month before landing the job at the grocery store, and that month was among the most miserable and exhausting of my life. At D & L, I stood on a concrete floor for eight hours a day, grabbing aluminum parts off a conveyor belt with my left hand and sticking them in a punch press, depressing a foot pedal while hoping I wouldn’t lose a finger. It was deadening, and every evening I left dog-tired. If you work at a job like that, and have to stop by the grocery store on the way home to shop for dinner, discovering that something you needed is not in stock can be deflating. Hanging around long enough to discover that it is in stock but not where you expected it to be, or hidden by something else, or expired, can be enraging.

According to a 2019 report from the USDA’s Economic Research Service (based on data from 2015), the median distance from a person’s home to the closest grocery store was 0.9 miles; the third-closest store was on average 1.7 miles away. Researchers found the proximity to the third-closest store to be a reliable indicator of the extent to which people may be said to live in a competitive market. When the researchers focused on rural areas, they learned that the median distance to the closest grocery was 3.1 miles and the distance to the third-closest was 6.1 miles. In the mid-’70s, the closest town to Cleveland with a well-stocked, full-service grocery store was Shaw, 10 miles away, and I’m stretching the meaning of “well-stocked.” What lay between those two towns was farmland, which explained why so many people who shopped at our store came in with dust from the cotton fields on their shoes and clothes.

When I worked for Mr. Williams, I knew nothing about his background. I knew only that he drove a new-looking pickup, that he always wore a clean white shirt with a necktie or bowtie and dark suit pants. What I have since learned from the obituary I found online is that he started working for the Blue and Gold grocery—the precursor of Sunflower Food Stores—when he was in high school. If my math is right, by the time he hired me, he would have been in the grocery business for about 20 years. I think that having worked hard for a long time, he really meant what he said: our customers deserved better. The fervor he brought to his job convinced me that I had better follow his example. Eventually, this work ethic became second-nature, and it carried over into many other pursuits, like studying, writing, and teaching.

I last lived in the Delta more than 40 years ago. I’ve spent nearly all my adult life in one of three locations: Fresno, California, where we lived for 21 years; the Boston suburb where we now make our permanent home; and Kraków, Poland, where my Polish wife and I live for a few months each year. In all these places, we could easily feed ourselves without ever stepping into a traditional grocery. Farmers’ markets abound, as do specialty shops. But I love grocery stores. In the lonely years before I met my wife, I sometimes went to one late at night just to see other people, and if you have never felt the need to do that, you might be surprised to know how many other people appear to be there for the same purpose.

Even now, more than four decades since I last worked in the business, I will seldom pass up the chance to walk the aisles of a grocery store no matter where in the world I might be. I read grocery stores the same way I read novels: with an insider’s understanding of how they deliver the goods. I also read them critically. Sometimes a store like the one where I worked will prove a pleasant surprise. Sometimes a store that ought to be first-rate will disappoint.

On a recent morning, I dropped into the closest store to our house, which is exactly the national median distance from our front door, 0.9 miles. It belongs to a national chain of luxury grocery stores. We like eating the healthiest food we can get, and we can find plenty of it there. We can also find healthy food, along with lots of not-so-healthy food, at the second- and third-closest stores, each of which is 1.8 miles away and offers much lower prices. But even though I don’t relish spending $9.29 on a gallon of my favorite orange juice when I could get it for around $3 less at the other stores, I happen to live in a town in which the south end of Main Street connects with I-93 and the north end connects with I-95. During the morning rush, which extends on weekdays for up to four hours, the interchange between the two highways produces some of the worst gridlock in the country; the scene is repeated in the afternoon and evening. Savvy commuters, some from as far away as New Hampshire and Maine, long ago learned that a detour onto Main Street might help them shave a few precious minutes off their commute. For several hours each day, downtown turns into a parking lot. So we generally avail ourselves of the closest option.

The first item on my shopping list was a head of romaine lettuce, going that morning for $3.29. I examined five heads before finding one without rotten leaves. As I continued through the produce section, I noted several empty bins. That is nearly always the case at this particular store, though it seldom happens at the chain’s Cambridge Street store in Boston, or at its Andover store. I knew from previous experience that the missing items were probably in stock but just hadn’t been put out. My second and third items, an 18-ounce carton of organic rolled oats and a bag of organic high-fiber oat bran, should have been close to each other on the cereal aisle. But today, the side of the aisle where I hoped to find them looked as if it had been subjected to artillery barrage, gaping holes everywhere. Fortunately, there were plenty of rolled oats. The oat bran, though, was not in its usual place. I spent a couple of moments running my hand over bags of wheat bran, muesli, almond flour, buckwheat cereal. Just as I was about trudge to customer service and ask for an inventory check, I found it on the bottom shelf, where it had never been in all my years of shopping there.

Though I needed nothing else, before checking out I gave myself the pleasure of visiting the pasta section, and that I morning I found what I always find there: a solid wall of perfectly fronted labels, row upon row of canned tomato paste and tomato sauce, much of it organic; whole tomatoes peeled, fire-roasted tomatoes diced; jar upon jar of pasta sauce, much of it exotically flavored and mouthwateringly tasty; box upon blue box of De Cecco organic pasta, a veritable Army of the Potomac, rank upon rank of silent soldiers ready to do their jobs as well as whoever stocked this immaculate section always did theirs. Here, at last, in a market that trumpeted excellence without always demanding it of itself, was something James Williams might have approved.