A Dream of a Writer

Peter Taylor’s stories reveal an artist immersed in the quotidian who rose to the complexities of the heart and psyche

Matthew Hillsman Taylor Jr., nicknamed Pete, decided early to become simply Peter Taylor. The name has a certain directness, as well as a hint of elegance. Both qualities were also true of his writing, though his directness was reserved for energizing inanimate objects, as well as for presenting physical details. (His sidelong psychological studies, on the other hand, take time to unfold.) It was also his tendency to situate his characters within precisely rendered historical and social settings. His stories deepen, brushstroke by brushstroke, by gradual layering—by the verbal equivalent of what painters call atmospheric perspective. Their surfaces are no more to be trusted than the first ice on a lake.

Born in Trenton, Tennessee, in 1917, Taylor was a self-proclaimed “mama’s boy,” though he said his mother never showed favoritism among her children: he had an older brother and two older sisters. She was old-fashioned, even for her day. He adored her, and women were often objects of fascination in his fiction. The women in Taylor’s stories are capable, intelligent, if sometimes unpredictable in their eccentricities as well as in their fierce energies and abilities.

How wonderful that all the stories are now collected in two volumes in the Library of America series (Peter Taylor: The Complete Stories, 1,650 pp., $75). A reader unfamiliar with Taylor’s work will here become an archaeologist; American history, especially the Upper South’s history of racial divisions and sometimes dubious harmonies, is everywhere on full display. Taylor was raised with servants. The woman who was once his father’s nurse also cared for him. Traditions were handed down, as were silver and obligation. Though he seldom writes about people determined to overturn the social order, Taylor never flinches when presenting encounters between whites and blacks—whether affectionate, indifferent, or unkind—and dramatizes them forthrightly.

The stories, rooted in daily life, use the quotidian as their point of departure into more complex matters. Writers have little use for the usual. Whenever a writer takes the pose that the events of his story are typical and ordinary, the reader knows that the story would not exist if this day, this moment, were not about to become exceptional. Taylor mobilizes his characters and the plots that they create as if merely observing, as if capably evoking convention and happy to go along with it. To add to this effect, he sometimes creates a character, often a narrator, whom the reader can take for a Peter Taylor stand-in: a child, a college professor, or a young man like Nat, the protagonist of his novella-length “The Old Forest,” whose thwarted desires and covertness about tempting fate are at odds with what society condones and also with his inexperience. In that particular story, one woman turns the tables and, in the closing lines, another woman—Nat’s fiancée, Caroline—kicks the table right out of the room. It is one of the most amazing endings in modern fiction, with a revelation that rises out of the subtext:

Though it [says Nat, referring to leaving home and rejecting an identity determined by others] clearly meant that we must live on a somewhat more modest scale and live among people of a sort she [Caroline] was not used to, and even meant leaving Memphis forever behind us, the firmness with which she supported my decision, and the look in her eyes whenever I spoke of feeling I must make the change, seemed to say to me that she would dedicate her pride of power to the power of freedom I sought.

The present tense of “The Old Forest” is the early 1980s, when Nat is a man in his 60s. The story’s action, however, takes place in a remembered 1937, just before Nat, then a college undergraduate, is to marry Caroline. His wedding plans go awry when, while driving near Overton Park in Memphis with another young woman, he has a minor car accident, after which the woman flees into the ancient woods in the park and disappears. The mystery of her disappearance must be solved before the marriage can take place. Nat, as narrator, has alerted us early on (no doubt so we might forget about it) that the story we’re about to read happened in the Memphis of long ago. It ends in an epiphany we never see play out. The future—the “now” of the story—is only eloquently suggested. The story of the 40 intervening years is barely, glancingly told—shocking as some of the few offered details are. Virginia Woolf’s surprising use of brackets to inform the reader of the death of Mrs. Ramsay in To the Lighthouse was stunning; Taylor’s narrator, who hurries through his account of family tragedies, is equally shocking, as the information he relays appears to be but a brief aside to the story he wishes to tell.

Every writer thinks hard about the best moment for a story to begin and end. Taylor does, too, but his diction—his exquisite and equivocal choice of words—often suggests that beneath the surface action of the story dwells something more, something uncontainable. With “pride of power” comes the hint that Caroline is fiercely leonine as well as heroically self-sacrificing. This, however, is projected onto her by Nat: it “seemed to say to me.” In other words, it’s worth noting that an idea has been planted, in both Nat’s mind and the reader’s, yet it is unverifiable; we do not get to read the story of a lifetime that might otherwise inform us or offer a different interpretation of what we’re asked to understand. Elegant prose, calculated to convince, appears at the story’s end—a literary high note, nearly one of elation, on which to conclude.

But I wouldn’t be sure. In retrospect, the story tells us a lot about Nat (perhaps that he can be as annoying as a gnat), who intermittently interrupts the narrative to inform us with disquisitions about the historical significance of the old forest. It’s a ploy to distract our attention from all that’s forming below the surface (“missing the forest for the trees”). Nat, writing from the perspective of maturity, knows himself, yet not entirely; he feels he must do the right thing, but does so only when prodded by Caroline, a strong woman. He is adamant that they must find another way, a new way forward in which something is lost (Memphis, his family, and their expectations of him) but something is also gained (autonomy and the ability to pursue one’s passion). All this leaves the lioness a little on the sidelines, and the present-day reader might be saddened that the Caroline of 1937 understands that her only way forward is to attach herself to Nat, a man—but, at the moment the story concludes, the two characters are united by the writer in their own version of triumph.

With apologies to the New Criticism (originated and practiced by some of Peter Taylor’s most important teachers, including Allen Tate, John Crowe Ransom, Cleanth Brooks, and Robert Penn Warren), here is where I conflate the life of the writer with the actions and thoughts of his stand-in character. The tension that arises within the protagonist from a psychological or emotional conflict is a common theme of Taylor’s stories. As is the idea of a trade-off or compromise. As is ambiguity, a feeling of unease that can creep over the reader like a shadow, so slow moving that it’s accepted without question. It’s not until later that one looks for its source, and there is where Taylor always outfoxes the reader. He will purposefully disrupt a story’s forward momentum to delve into the narrator’s past, causing what might seem to be equilibrium, when jammed up against the story’s present moment, to create disequilibrium.

What makes me so admiringly queasy is not this juxtaposition and the discordant tone it sounds but what the methodology evokes more broadly: Peter Taylor, as writer, occupying the role of both Orpheus and Eurydice. He repeatedly creates narrators who guide the reader through the story toward an expected and just resolution but who then hesitate, or momentarily lose their moral focus, and so scuttle that resolution. Taylor’s characters want to come out into the light, but the person who can best guide them, the writer himself, is impelled to make them look over their shoulder and face the omnipresent past, with all its implied demands. The possibility of faltering, the probability of it, is a recurring undertow in his stories. It’s as if, in his worst fears, Taylor, relegated to Eurydice’s powerless and inescapable position, might himself need rescuing. The way out is never easy or clear, even with a narrator’s guidance, and so daunting that one can’t go it alone. Taylor’s main characters always need to bring someone with them; individuals, in Taylor’s fiction, must exist in pairs. After all, his narrators are mortal.

The writer’s use of intrinsic doubt—of aporia as a rhetorical strategy—is also fascinating. Just when we’re almost hypnotized by the narrative abilities of some of his eloquent yet dissembling characters, there comes a shift in tone, really a sotto voce moment, in which the narrator second-guesses himself or the tale he is telling, thereby indicating that everything the reader hears must not be taken at face value. Quite a few of his stories verge on being mysteries (“The Oracle at Stoneleigh Court,” “First Heat”), though not the conventional kind that pose suspense-filled puzzles that will eventually be solved. Rather, Taylor’s puzzles are articulated so that some potential accommodation, some new way to go on with one’s life, may become apparent. Though the reader may not register it immediately, at the end of a Taylor story some essential riddle remains.

Peter Taylor embodied contradictions. He often explored them in his fiction, though rarely does he leave us with a feeling that things have been comfortably reconciled for himself or his characters. There remains an oscillation, an internal push-pull, as if the mind were a vibrating tuning fork. Currently, in the age of memoir, there’s a lot of self-important talk among writers about writing as a means to self-salvation. To the extent that this applies to Taylor, his characters are proof that the energy generated by inner turmoil is synonymous with really living. Take his story “Je Suis Perdu” as a beautiful example. Its real-life point of departure is that the Taylors, in the mid-1950s, went to France with their two young children. The story chronicles a day in the life of an unnamed American husband and father (he is 38) who is morbidly preoccupied with aging and mortality. As always in fiction, this day starts as a usual day—the day before he and his family leave Paris. Our protagonist goes to the Luxembourg Gardens, where Taylor begins to expose him to various backdrops, beginning with Poe-like monstrous façades. His thoughts turn to the French painter David and his only landscape, an oil-on-canvas view from the building in which he was imprisoned. We can’t fail to understand the import of this implied link between the two men. The character also considers the Panthéon, the mausoleum for France’s secular saints, projecting his dark mood so that it, too, is personified into monstrousness. Late in the story, our protagonist seems to be suddenly overwhelmed with a kind of emotional vertigo, along with the disoriented reader: “When the mood was not on him, he could never believe in it.” Taylor is always aware of individual words, and all they might convey: significantly, it is “the” mood, not “his mood.” It becomes “his”—it is personalized—only on the last page of the story.

Yet again, the writer provides us with a psychological study (this one more explicit than most), not to solve the mystery of his protagonist’s conflicting moods but rather to create anxiety with its articulation: it is a beautiful day in Paris; he loves his wife and children; he’s been away from his job in America, working on a book he has just finished. Aha. So this is also a story about writing, and about one writer’s personal demons being projected onto the external world. Consider the “cute” antics of his baby son, which impress the reader as more grotesque than humorous, the boy’s spinning reminiscent of the devil’s; also, his wife, who, in her slip, does not disrobe but instead gives him the slip as she goes off to dress; and his daughter, who is too tightly wound, her shrieking portending the nightmarish perceptions that will soon overwhelm her father.

The story is divided into two sections, titled after Milton’s pastoral poems “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso.” Sometimes described as paired opposites, each poem actually embodies its own contradictions in an embedded complexity that would appeal to Taylor, who never thought in terms of either-or. Also, Taylor would never invoke Miltonic high seriousness if not to alter it—in this case, by wittily playing against it. This is a story about a man who should be all right, but who isn’t. Its ending is qualified by the indelibility of every revelation that, earlier in the story, we’ve been so immediately immersed in; Taylor overwhelms both reader and character with the intensity of the character’s inner conflict. Our own moods plunge as we read. Here’s what the writer depends on: once we see something, we can’t not see it; once we feel something, we can’t be told we don’t. It sounds so obvious, but few writers have the mastery to haunt the reader long after their characters have ostensibly shaken off their demons. The story’s final paragraph, with ellipses that convey what must remain unspoken, the “buts” still too painful to articulate, expresses a tentativeness that purports to end with enlightened awareness: “But this was not a mood, it was only a thought.” This sounds like an important distinction, yet it’s more likely that the character is grasping at straws—word straws—desperate to regain (or at least feign) equilibrium. We, however, have felt the bleakness of his mood; we retain the after-image of the Panthéon transformed into a glaring monster.

Near the story’s end, Taylor expands his horizons: we find ourselves reading an unexpected parable about America, and furthermore this consideration—which we now understand has been a significant part of the subtext—mitigates the ending’s potential upswing. We’re taken aback, just as we are at the end of The Great Gatsby, though without the enlightened exhilaration. In Taylor’s story, as in Fitzgerald’s novel, one has gone to a foreign land (in Gatsby we hear about the Dutch sailors; the characters’ predecessors have also moved, in Taylor’s story, to a new frontier); the protagonist of “Je Suis Perdu” has become something of an actor (he grows, then shaves off, his mustache; Gatsby, with his rainbow of colorful shirts, has nothing on this guy). Time and again in Taylor, the visitor is never, ever, truly accepted, however well he tries to act the required role. It’s the status quo that our protagonist desperately returns to—or tries to—at the end of “Je Suis Perdu,” words his daughter utters that, we come to understand, expand in their connotations so that, metaphorically, we see it is he, the father, who is lost. We know “the mood” will descend again.

An admirer of Hemingway (there we see shadows before we suspect the source), Taylor, as his talent matured, increasingly turned toward another early influence, Henry James. Taylor has also been compared (too often and too easily) to Chekhov. He admitted that he learned a lot from the Russian, particularly how to consider things from many perspectives. But in reading or rereading Taylor’s work after many years, I was struck by certain other influences that I’d previously passed over: Freud, for example. (Taylor, on being sent students’ analyses of his story “A Walled Garden”: “As I read their papers, I began to think, ‘Well, you know, that didn’t occur to me while I was writing it, but in a way that’s why it works as well as it does.’ ” It’s not unusual for writers to write from an unconscious level, though Taylor’s level-headedness—at least in interviews—seems so atypically rational, one wonders whether he isn’t being a bit coy in his modesty.) I was surprised at the number of times the progression of a story and its symbols seemed so obviously Freudian, or to hint at allegory. When Taylor began writing, psychoanalysis and Freud’s surprising new ideas were in the air. Freud’s and Jung’s ways of thinking were part of the cosmology of some of his closest friends and fellow writers, such as the poet Robert Lowell.

Taylor did not compose in a white heat, though, or dash off rough drafts. He was an urbane, educated man who also clearly perceived the world intuitively and through his senses. He was keenly attuned to tone, timing, gestures, and subtleties. Taylor was also a playwright, working in a mode that informed his fiction. Time and again he lets us see people acting, whether they’re gazing into a foggy mirror, as in “Je Suis Perdu,” or rationalizing aloud a bit too much, as Nat does in “The Old Forest.” Taylor’s habit was to compose a text over many months, which makes me wonder how often he must have stared at the wallpaper, only to suddenly see an alternate, hidden pattern emerge. His involvement in art began with a childhood desire to paint, an aspiration he shared with other highly visual writers such as John Updike and Elizabeth Bishop. He drew his dreams. Perhaps more than he let on, he trusted unconscious forces.

A case could be made that his writing conveyed so much immediacy because, awake, the writer was trying to connect the dots, ashes of a dream that lit up here and there unexpectedly, in the moment of its being dreamt. Though the dreamer cannot be both dreamer and interpreter of the dream, there’s no prohibition against waking up, remembering, pondering, and incorporating the dream’s meaning in its reshaping into a story. Taylor often deliberately immerses the reader in the illogic of a dream (“Demons,” “A Cheerful Disposition,” “The Megalopolitans”) and gives us a visceral sense of how that feels. With guidance (his conscious mind perfects the story), its symbols, when they have their dots connected, form the character’s personal psychological map—one that at times we are better able to understand than the character can.

Taylor was also interested, at least as a subject of fiction, in the occult, in tarot cards, in ghosts—as was Henry James. Reading Taylor, one is reminded more than once of James’s “The Jolly Corner.” Of course this story would appeal to Taylor, with its hints of what is unseen becoming manifest, and the implied question of what one’s life would be like if it could be relived. Taylor’s early story “The Life Before,” which appeared in the Kenyon undergraduate magazine Hika, shows his interest in characters who are haunted: the protagonist and his wife conjure up their guardian angel, a seemingly ageless man named Benton Young, who appears in the doorway of the hotel in which they live to remind them of the power of his love, which comes as a kind of blessing to these two people who each love him in different ways. There is much more to the story, but placed in a context of his other “ghost” stories, and his collection of one-act plays titled Presences (1973), this early story is a little unsubtle in technique, yet also significant. (One can understand why plays appealed to Taylor: “In fiction you’ve got to prepare for the ghost for pages and make it right, whereas in a play you just say, ‘Enter ghost.’ ” Taylor could be quite witty.)

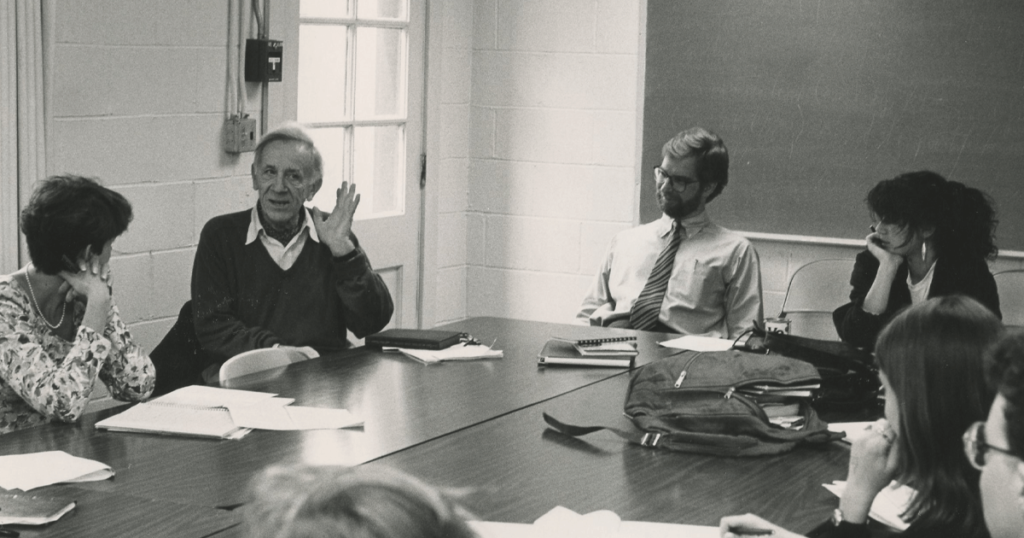

Socially, Taylor was a raconteur who never told stories for easy laughs any more than he let them inflate into tragedies. I met him in 1975 and remained a friend to him and his wife, Eleanor, for the rest of their lives. He and his former student John Casey were the people who got me hired at the University of Virginia when I was 25. Was I awestruck? Not really, because he made anyone he befriended feel so comfortable. Was I intimidated by his wizardry in constructing a story? I just assumed anyone who could write stories like his was a genius. Do I wish I’d asked him questions about everything from what books to read (his students were treated to this, because he read aloud in class) to how certain effects were achieved in his own fiction? At the very least, couldn’t I have interviewed him? I’d like to go back in time and give my younger self a shove. But I got from him, because of his attention as well as his talent, what some other lucky people also received: the idea of how a person might have a life in writing.

In the early stories, and even more so in the later ones, his narratives zig and zag through time as he gestures to other literary texts, and sometimes to works of visual art, with which his writing is in dialogue. Many of the stories (particularly the longer ones) are intended to approximate oral storytelling, rich in episodic digressions and a mixing of the important with the seemingly unimportant. Readers perceive different connotations, different connections, depending on their level of literary awareness. “A Walled Garden,” for instance, is a prolonged apostrophe that sounds more than a little like one of Robert Browning’s dramatic monologues, though anything Taylor took in was made his own.

“Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time,” written in the indirect third person (until the anonymous narrator, having cleared his throat for 25 pages, at last steps forward), asks us to believe a narrator who casually assumes that his views and the reader’s coincide, yet who also informs us of things no one else would realize or put together in the same way. At the heart of the story is an account of the last of the annual parties given by Mr. Alfred Dorset and “his old-maid sister,” Miss Louisa Dorset, for the children of provincial Chatham, Tennessee. Brother-sister incest, the story’s subtext, is never observed but instead is displaced, prismatically: we see many puzzling points of light before the picture that the narrator is painting comes into focus. We “see” it in its pictorial or visual equivalents—lovemaking arrested in time (an echo of Keats?) as depicted in Rodin’s sculpture The Kiss, as well as in the busy Bronzino canvas that gives the story its name. There the naughty Cupid fondles his mother’s breast, while the child Folly, rushing up behind them, prepares to shower them with a fistful of rose petals. These images—together with a plaque of Leda and the Swan—hang on the walls of the Dorsets’ home. Into this highly sexualized setting comes an adolescent named Tom, whose actions disrupt the children’s party and upend the lives of its hosts. If the reader hasn’t suspected it before, the “uninvited guest” of Taylor’s story is played against that of Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death,” though the stakes are not quite so sensational, or so deadly; instead, they remain murky and hauntingly disturbing, since there is no one form of evil to unmask. “Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time” also, in places, mimics a fairy tale. By extension, it might be America’s fairy tale about itself, gone wrong: “The wicked in-laws had first tried to make them [the brother and sister] sell the house, then had tried to separate them …”

Taylor is a writer who so loves to keep our senses sharp; our eye is forced to work like a borer bee as it moves closer to the deeper meaning below the intricately contrived surface pattern. In this story, the calculated miscalculation of a teenager’s joke—a mock seduction—echoes the off-the-page “real” seduction (the incest of the Dorsets, who, as Miss Louisa tells us, “have given up everything for each other”). All this is played against the backdrop of sexually evocative sculpture and painting—to which is added the suggestion that time (and sexual maturity) does, and does not, change everything. The old siblings being teased, in the reader’s presence, have already been relegated to twisted figures depleted by time: the sister, symbolically wearing (like a wedding dress) a “modish white evening gown, a garment perfectly fitted to her spare and scrawny figure … never to be worn but that one night!”; her brother, like a Tennessee cousin of Gustav von Aschenbach in “Death in Venice,” “powdered with the same dark powder that his sister used.”

The use of exclamation points in this story is purposeful: they indicate faux surprise and mock the Southern Gothic horror genre, which insistently telegraphs its shocking revelations. In the claustrophobic funhouse Taylor has orchestrated, his narrator blithely tells us things as if telling a conventional story, the author withholding many metaphorical exclamation points of his own. This amazing tour-de-force, which has been much anthologized, must have gone over many of its first readers’ heads like a shooting star. A bit meanderingly and imperfectly told, it’s meant to read like the transcript of a spoken story. The repeated use of the conjunctions “and” and “but” to begin sentences says everything: and means there is a connection between things; but means that that connection is not absolute. Also, the story’s location, the fictional town of Chatham—described by some as “geographically Northern and culturally Southern,” and others “say the reverse is true”—puts us on a fault line, in troubled and troubling territory that makes everything liminal. With a historical perspective introduced only in the last pages of the story, we’re made to understand that the mercenary, mercantile Dorset family opportunistically settled Chatham “right after the Revolution” and then, in the early 20th century, abandoned it—“practically all of them except the one old bachelor and the one old maid—left it just as they had come, not caring much about what they were leaving or where they were going.” The rape of the town echoes the rape Taylor has earlier alluded to in the Leda and the Swan plaque; it also keeps the suggestion of incest ambient. Heedless people. Opportunists, Taylor intends us to see—analogous to those who grasp for what serves their purposes to embrace.

Taylor was a southerner whose best friend was Robert Lowell, a Boston Brahmin. It’s possible that, for reasons of his own, he put a positive spin on some of Lowell’s pointed needling and, ultimately, neediness. (Taylor once told an interviewer that Lowell “invented facts and stories that made his dearest friends out as clichés … cliché Jews, cliché Southerners, cliché Englishmen. Naturally this was irksome sometimes—even mischief-making. He was fond of representing me as a Southern racist, though of course he knew better—knew it from the hours of talk we had had on the subject, as well as from my published stories. … His teasing was often rough but … it was his way of drawing closer to his friends, rather than putting them off.”) It seems equally possible that sometimes Taylor was hurt, though he always remained Lowell’s loyal friend. Taylor was in some instances quite sure of his feelings: he knew, for example, that as a young man he must stand up to his father—even if it meant refusing to attend Vanderbilt, his father’s choice of university for him. (He did later attend Vanderbilt, but for his own reasons and on his own terms.) He knew the first time he saw Eleanor Ross that he would marry her and waited only six weeks to do so. Their long marriage lasted until his death. As for finally wearing a somewhat ironic crown, in 1987 he received the Pulitzer Prize for a novel, A Summons to Memphis, yet thought of himself as primarily a short story writer. Like all of us, at times he revealed more than he knew. He explained his election to the American Academy of Arts and Letters by mentioning that there were “no dues or anything like that.” I love the slight naïveté, as well as everything implied in the phrase “anything like that.”

In Charlottesville, one didn’t see him on the golf course or riding with the horsey set. Though he taught at a great many colleges and universities—in the East and the Midwest as well as in the South—he returned in the end not exactly to the foul rag and bone shop of his heart but, with fondness, to a place he thought of as a prestigious, known entity: the University of Virginia. In what might or might not be a contradiction, he taught creative writing while remaining skeptical about whether there should be a creative writing program. When he retired, he and Eleanor continued to live in town. Eleanor, herself an accomplished poet, liked to garden. If she’d written a poem during the day, no visitor was told. Quite a few of his students and former students became his friends. Robert Wilson, the editor of this magazine, accompanied him to Paris to receive the Ritz Paris Hemingway Award. Dan O’Neill, a student who later became his real estate agent, drove a rented van to Long Island to fetch Jean Stafford’s settee (a wonderful Tayloresque word that has vanished from the vocabulary), which she’d willed to Peter and Eleanor. (Only after her husband’s death did Eleanor say she didn’t much like it.) A former student routinely drove the couple to Florida in the winter. They bought a house in Gainesville near Eleanor’s sister, Jean, who had married the poet Donald Justice; earlier, they’d lived in Key West. Oddly—or maybe significantly—while wild tales of Tennessee Williams and, more recently, the bon mots of James Merrill are as essential to the residents of Key West as the literary air they breathe, there is no plaque on the Pine Street house where the Taylors lived, nor is there any Peter Taylor lore.

Peter and Eleanor were real estate enthusiasts. They bought and sold and repurchased a house, only to later sell it again. They came for dinner and, if you were renting, asked if you knew whether the house was for sale. Taylor showed pictures of properties they were considering when Eleanor left the room. Eleanor, in the kitchen, would earlier have laid out photographs on the breakfast table of her own recent house fascinations. They rented Faulkner’s house in Charlottesville but, unable to buy it, bought the house next door. Later, they moved a bit closer to the university. But I don’t believe they ever owned only one house, even when curtailed to one location after Taylor’s heart trouble worsened.

Their preoccupation with houses was surprising and a bit eccentric, but houses and their home-obsessed inhabitants are everywhere in his fiction. Never props, houses (apartments and hotels, as well), along with their furnishings, are given the stature of characters. The characters are an outgrowth of the life lived within, as well as the houses’ being significant because of where they’re located, how they’re used, and what details have been described in such highly visual terms that they convey indelible meaning throughout the story. The houses are as integral as a shell is to a turtle. And, like a turtle, they suggest that no one’s going anywhere fast. In spite of life’s flux, houses give the impression of being constant.

Taylor isn’t Hawthorne or Poe (he admired them, but their pyrotechnics didn’t reflect his sensibility; if they were the fireworks, his stories would be the just-struck match). He did have the ability to create his own sort of visceral scariness—one that rarely had anything directly to do with obvious projection or personification (“Je Suis Perdu” is an exception that proves the rule). Here is Peter Taylor, talking to an interviewer in 1985:

I like to do landscaping. On the last place I had I built three ponds, one spilling into the other—18th-century style. And that’s what I’ve done to this place. It’s got great boulders on the side of the hill, rocks as big as this room. And it’s very beautiful. I was even building an imitation graveyard, a topiary graveyard with carvings and shrubbery. It was pure folly. And Eleanor’s planted acres of trees. Then there are a lot of blackberries, persimmons to be gathered and that sort of thing.

Of course, his saying this, and making the “folly” we’ll never see so vivid, reminds me of how important his dreams were to him, how Freudian the implications of some of his stories are, as well as of his own use of allegory. It’s almost astonishing, how easily we can read into his words and understand that he is speaking simultaneously about a literal and symbolic landscape (as in dreams). When he described his property, he was already suffering from heart problems. He doesn’t reflect on his statement or in any way let on that he knows what he’s said, but it’s easy to see that the topiary graveyard conveys both his concern with mortality, and the careful artistry, the pruning-writing that he undertakes; landscaping is a metaphor by which, in creating an ideal world, he wishes to prove he’s powerful—still alive.

To read a great number of his stories is to sense an invincibility about Taylor’s dwellings that makes them a force to be reckoned with. Within these houses—as within all of us—must be secrets, areas of disrepair, covert demands exerted. One of his major considerations as a writer is the clash of past and present, the old order versus the changing world, Nashville versus Memphis. This evolution asks important questions about who we are, where we belong (and whether we can ever really leave those places), and what meaning to ascribe to exteriors, compared to (psychological) interiors. In the stories, we sometimes hear angry words from a character, a roar, occasionally hysteria—though no reader would typify his material by these outbursts. When things go out of control, in life or in fiction, they rarely devolve into complete chaos (war zones excepted), though it’s true that Taylor tends to play in quieter territory.

Has he not had the reputation he’s so long deserved because it takes a while for his subtle, disturbing stories that gestate below the surface to settle in? Was his magic act of now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t a bit too successful, a ruse that ultimately became counterproductive? His proclivity toward selecting narrators who have a cordial, confiding tone was trickery, but may have misled some readers into thinking that he was a nice southern gentleman, indistinguishable from his fictional creations.

It’s also possible that his reputation is a rare case of a short story writer’s being eclipsed by the poets of his generation, Lowell foremost among a group that also included Randall Jarrell and the now iconic Elizabeth Bishop. Another factor may be that southern writers, with such notable exceptions as William Faulkner or William Styron, were once considered regional writers, whose voices did not rise to universal truths. This is not the case today, if it ever was, so it can be easy to forget that there was a time when the term “regional writing” carried negative associations, and things southern were thought a bit unsophisticated. In some ways, Taylor’s discursive, chatty stories played into a stereotype about pawky storytellers whose horizons were obscured by the hills of home. During Taylor’s last years, it was Eudora Welty and Flannery O’Connor who were celebrated as examples of the quintessential southern short story. Meanwhile, he struggled to get his stories and books into print (in any case, he was never prolific), and his critical reputation became wobbly; had it not been for the admiration of such distinguished writers as Anne Tyler and Joyce Carol Oates, his reputation might have dipped further.

It’s rarely easy to find and keep an audience when a writer is publishing only intermittently, especially when that writer is not easily categorized: Taylor alternated between genres; he composed stories in verse (some of his rough drafts—in fact, every story in In the Miro District—initially took this form); he did not write essays and seldom reviewed books. He did not live in New York City, and time has proven that The New Yorker, which never exactly stopped publishing him, should have been more amenable to more of what he wrote.

Taylor advised writers to find a teaching job that would allow them time to write—conservative, no doubt practical advice, though having done that, he himself moved from job to job. He valued as the greatest compliment having the admiration of his peers, which he certainly did have. He thought small literary magazines were where a beginning writer could attract an audience and be encouraged as one built a reputation. Now, with so few commercial magazines printing fiction, and Kenyon Review and The Southern Review (among other magazines where he first published) still going strong, he turns out to be right.

Taylor once remarked,

Flaubert says, “Madame Bovary, c’est moi.” How can you write fiction if you can’t imagine it? And how can you imagine it if you don’t link your psychology to your characters? Writing starts with events and experiences that worry me, and I put them together. You write a story in which you are the protagonist, but you have to change him for the theme’s sake.

As always, he’s very clear about what he believes. It is the reader’s good luck that he worried. His best stories rise to the level of transcendent worry. He’s capable of making us—when we finish reading one of his more complex works—look upward from planet Earth, and from the South in particular, to a blue sky, or a dark sky, just waiting to be projected upon.