A Giant of a Man

The legacy of Willie Mays and the Birmingham ballpark where he first made his mark

The timing was uncanny, a bit charmed even, but then again—during a Hall of Fame career that spanned nearly a quarter of a century, and that led him from the Jim Crow South to New York to San Francisco and then back east—Willie Mays had nothing if not exquisite timing. Mays passed away in mid-June, age 93, two days before the San Francisco Giants faced the St. Louis Cardinals in a game organized to honor both him and the Negro Leagues. The venue was Rickwood Field in Alabama, the oldest ballpark in the country, where a 17-year-old Mays got his start with the Birmingham Black Barons. And it was at Rickwood where word spread that Mays, too ill to attend the ceremonies, had died, turning the event into a memorial as much as a celebration.

Mays played baseball with a style and grace that seemed practically mythical: his astonishing athleticism prompted the actress Tallulah Bankhead to declare him the only genius besides Shakespeare. Never before had the game produced a player with his combination of power, speed, and arm strength. He’s best remembered for The Catch: the over-the-shoulder grab in Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, in the cavernous depths of New York’s Polo Grounds. But Mays often said he had made better catches, ones that weren’t captured for posterity. It was a reminder that he straddled two distinct worlds during his playing career: one in the Negro Leagues and one in the majors. In the former, he plied his trade in relative obscurity; in the latter, his exploits were broadcast to the nation. In the gulf between the two resides a legacy that resounded far beyond the confines of center field.

A high school star born in Westfield, Alabama, Mays signed with the Black Barons on July 4, 1948. His pay: $250 a month. “He thinks he’s Joe DiMaggio, but he can’t hit a curveball none”—that was the scouting report that Mays’s father, who had played semiprofessional baseball, gave to Piper Davis, one of his former teammates and the Black Barons manager. A year earlier, Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier in the majors, and scouts were flocking to the Negro Leagues, searching for undiscovered talent. Not that the playing field had, in one pioneering moment, been leveled. Some major league teams had unofficial quotas for Black players; some wanted to sign stars only to bury them in the minor leagues, preventing rival teams from employing their services; some, like the Boston Red Sox, resisted integration altogether. So Mays’s preternatural talent wasn’t enough—making the jump to the majors also demanded political finesse.

Davis did his part to prepare Mays for the kind of abuse Robinson had endured during his rookie season. And he instructed Mays’s teammates to watch over him: no late-night carousing or womanizing.

Life in the Negro Leagues required constant concessions to the realities of Jim Crow—realities that Mays had grasped as a boy, when police would break up mixed-race pickup baseball games at local parks. He and his Black Barons teammates struggled to find hotels or restaurants that would serve them; they sometimes slept in flophouses or on the team bus. En route to a game at the Polo Grounds against the New York Cubans, the bus—a 22-seater, no air conditioning—caught fire in the Holland Tunnel. The team’s uniforms and equipment went up in flames, but not before Mays rescued his suitcase, which contained a collection of new suits. After he signed with the New York Giants in 1950, joining the team’s Class B affiliate in Trenton, New Jersey, he was greeted by racial slurs during his first game in Hagerstown, Maryland. He was often forced to dine and room apart from his white teammates; to alleviate some of the loneliness, the Trenton manager, Chick Genovese, sometimes ate with him in restaurant kitchens.

When the Giants moved from New York to San Francisco, Mays and his wife agreed to purchase a house on Miraloma Drive in Sherwood Forest, only to have the seller renege after neighbors expressed outrage over a Black family’s moving in. The mayor intervened; the sale went through. Soon after, someone threw a Coke bottle with a racist message tucked inside through the front window. Activists implored Mays “to solve the world’s problems, or at least those troubling America,” he wrote in his autobiography. “This, I refused to do. I had a narrow framework of operations I was comfortable with.” Or, as he told the writer Roger Kahn, “I help. I help in my way.”

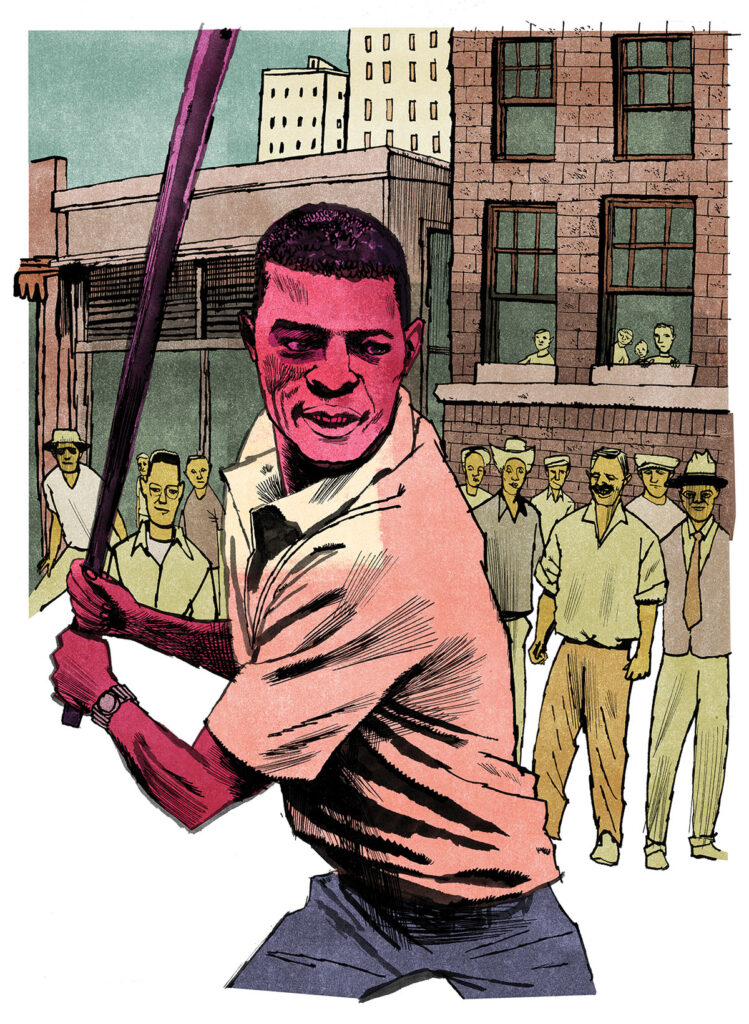

When he lived in Harlem during his early years with the Giants, the neighborhood children would knock on his apartment window on St. Nicholas Place, imploring him to join them for a game of stickball. More often than not, he obliged, taking cuts in a polo shirt and trousers, before treating the kids to ice cream cones and then walking over to the Polo Grounds for an afternoon game. He mentored those in need, including O. J. Simpson, who ended up in San Francisco Juvenile Hall after robbing a liquor store at the age of 14. And in 1966, when a white police officer in San Francisco shot and killed a Black teenager, sparking an uprising near the Giants’ home stadium, Candlestick Park, Mays recorded a message imploring residents to tune in and root for the Giants—words credited with helping calm the tensions.

In 2020, attempting to atone for its shameful legacy of segregation, Major League Baseball announced that the more than 3,400 Negro Leaguers who played between 1920 and 1948 would be recognized as major leaguers. And in May of this year, Negro League statistics from those years were added to the major league record. Mays, previously credited with 3,283 career hits, gained another 10 from his stint with the Black Barons. But his home run total remains at 660 even though newspaper articles record his hitting multiple dingers with Birmingham: no box scores exist to verify those blasts.

These statistical revisions are, of course, an imperfect mea culpa; they cannot undo the game’s original sin. But the announcement has symbolic resonance. It’s a reminder that the major leagues weren’t major until full integration, a reminder of what all the sublime Negro League ballplayers like Josh Gibson and Buck O’Neil and Satchel Paige achieved despite segregation, a reminder of what was lost when they were denied equal access to the national pastime.

If any ballpark embodied the longstanding divisions in the South, it was Rickwood Field, constructed in 1910. The Black Barons shared the ballpark with their white counterparts, the Barons. Seating was segregated, and the Black section during Barons games was known as “the coal bin.” In 1924, the Alabama Ku Klux Klan rented the stadium to initiate new members. And Rickwood was where segregationist Bull Connor first made his name, working as a stadium announcer, before later serving as Birmingham’s commissioner of public safety. In 1963, Connor ordered the arrest of Martin Luther King Jr. and set loose police dogs and water hoses on the civil rights protesters who had descended on the city. His was the ordinance that prevented Mays from playing mixed-race baseball games in his youth. But Rickwood was also where Mays first learned how to hit a curveball, where he glimpsed a future that was once unimaginable to his father—and to Black players of previous generations.

Shortly before his passing, when he realized he couldn’t travel to Birmingham for the Giants-Cardinals game, Mays released a statement. “I had my first pro hit here at Rickwood as a Baron in 1948,” he wrote. “And now, this year, 76 years later, it finally got counted in the record books. Some things take time, but I always think better late than never. Time changes things. Time heals wounds, and that is a good thing.”

If you’ve never been to Rickwood, consider making a pilgrimage to that intimate jewel box of a stadium and communing with the spirits of Mays and the rest of the Black Barons. What better way to remember where they started and how far they went, and what was required of a young man from Alabama along the way.