A Life Written in Invisible Ink

In her rebellious and much-celebrated poetry, Adrienne Rich both deciphered and created the feminist world she inhabited

I have been standing all my life in the

direct path of a battery of signals

the most accurately transmitted most

untranslateable language in the universe

—“Planetarium”

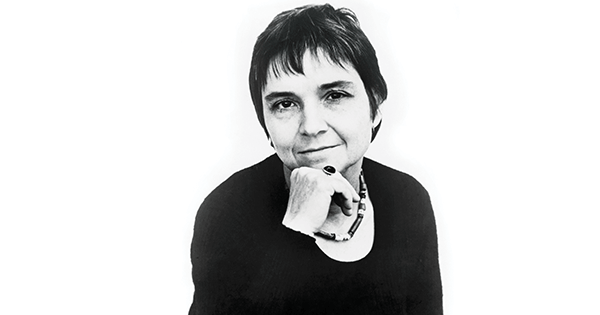

Adrienne Rich was, without question, the unofficial poet laureate of 20th-century American feminism. Over the years, as she evolved from a stereotypical “daddy’s girl” and a precocious disciple of W. B. Yeats and Wallace Stevens into an aesthetic, critical, and political pioneer, she became a prophet for both the women whose causes she championed and the country whose flaws she lamented and whose transformation she envisioned. Many critics thought her crotchety or, worse, “strident,” while she herself sometimes said that she spoke from a marginalized perspective. Even women who might have been sympathetic to her ambition complained about her. Two éminences grises of The New York Review of Books castigated her feminism: Susan Sontag dismissed it as “a bit limited,” and Elizabeth Hardwick fretted that she “deliberately made herself ugly and wrote those extreme and ridiculous poems.” Yet during her lifetime, Rich won countless prizes, including a National Book Award, a MacArthur Fellowship, the first Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, a Bollingen Prize, and the Lannan Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award. When she died at 82, in 2012, Margalit Fox, who composed her New York Times obituary, aptly characterized the ambiguity of her position, describing her as “a poet of towering reputation and towering rage.”

“Towering rage”—no one would have expected such passion from the preternaturally expert 20-something who won the Yale Younger Poet’s prize in 1951 for a first book tellingly titled A Change of World, which arrived with a commendation from W. H. Auden that is still infamous. Her poems, declared Auden, who had chosen them for the distinguished Yale series, were “neatly and modestly dressed, speak quietly but do not mumble, respect their elders but are not cowed by them.” A few years later, in patronizing words on her next volume, The Diamond Cutters, Randall Jarrell made things worse, writing that the author of the book seems “to us a sort of princess in a fairy tale.” That the young woman responsible for these two collections was a serious student of English and American verse tradition with an extraordinary verbal gift and an impressive command of prosody—the kind of formal skill especially admired in the ’50s—makes these remarks seem especially odd today, when we inhabit a literary world that has been significantly altered by, among others, the powerful author of A Change of World. Yet it is from the midcentury American culture whose implicit assumptions about gender and genre were arguably defined by Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique that Rich journeyed toward her major accomplishments, achieving stature through, in her own words, “a succession of brief, amazing movements / each one making possible the next” (“From a Survivor”).

Rich’s life, like her writing, was marked by dramatic metamorphoses, changes that reflected, even while they influenced, the world that was radically changing around her. Her growth, observed the poet-critic Ruth Whitman in 1975, was “an astonishing phenomenon to watch: in one woman the history of women in our century, from careful traditional obedience … to cosmic awareness, defying the mode of our time.” Like Yeats, the poet she most admired when she was an undergraduate, Rich evolved from phase to phase as, increasingly, she elaborated the politics of her aesthetic in essays that can be read along with her poems as both manifestoes and glosses. In prose and verse, she herself remarked on these transformations, sometimes almost with wonder. A dutiful child, she was homeschooled for some years by a strict pianist mother, who taught her to play Bach and Mozart, and more overwhelmingly, by a scholarly pathologist father who set daily literary tasks for her and her sister. “I think he saw himself as a kind of Papa Brontë,” she once wrote to the poet Hayden Carruth, “with geniuses for children.” (Her unpublished letters to Carruth appear in “The Wreck,” an article by Michelle Dean in the April 3, 2016, issue of The New Republic.)

But beneath a veneer of decorum, the stubborn poet had begun to stir. In secret, she confided to Carruth, she “spent hours writing imitations of cosmetic advertising and illustrating them copiously,” and “mercifully,” she recalled in print, she “discovered Modern Screen, Photoplay, Jack Benny, ‘Your Hit Parade,’ Frank Sinatra,” and other icons of popular culture. Worse still, though from her father’s perspective she was “gratifyingly precocious,” she confessed in Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution that she had “early been given to tics and tantrums.” Even in the years when Auden and Jarrell were captivated by her command of versification (“I was exceptionally well grounded in formal technique,” she herself admitted in What Is Found There, “and I loved the craft”), she was “groping for … something larger.” Her first act of overt rebellion against Papa Brontë was to marry “a divorced graduate student.” Then, as she sardonically noted in Of Woman Born, she began to write “ ‘modern,’ ‘obscure,’ ‘pessimistic’ poetry,” and eventually she had “the final temerity to get pregnant.” Another young woman poet who visited Cambridge at this time discerned what Auden, Jarrell, and perhaps even Rich’s father had failed to grasp. Sylvia Plath was fiercely rivalrous toward Rich, but in her journal she described her, with some respect, as “all vibrant short black hair, great sparkling black eyes and a tulip-red umbrella: honest, frank, forthright and even opinionated.”

When Plath encountered her, Rich had ostensibly settled into marriage and maternity. Her husband, Alfred Conrad, a Harvard economist, was simpatico and reasonably supportive. Yet soon enough the young poet began to rebel against the implications of her own decision to bear children in her mid-20s. In Of Woman Born, another classic text of ’70s feminism, Rich examined with unusual frankness the anxieties and ambivalences of maternity. Though she confided that she loved her sons deeply—and was evidently close to them throughout her life—she argued that “every mother has known overwhelming, unacceptable anger at her children.” And at her husband. For like Plath, Rich was slowly skidding toward a marital breakup. Unlike Plath, she survived the pain. Instead, seven years after Plath gassed herself in a London oven, leaving two children for Ted Hughes to raise, Alfred Conrad drove in a rented car to the family’s Vermont country home and shot himself, leaving his wife with three young boys and a weight of grief that went for many years unwritten.

Inevitably, biographical pressures shaped the work of both Rich and Plath. Though each fictionalized or screened personal crises in sometimes evasive or obscure metaphors, each might be said to have lived what Keats once called a life of allegory, “a life like the scriptures, figurative.” But because Rich outlasted Plath for so many years, she was able through the “amazing movements” at which she herself marveled to become a feminist warrior for yet further change. And many of her readers, especially those of us who were poets and feminists, detected the revolutionary urge even in her most elliptical texts. We knew that traditional marriage hadn’t worked for her, as it hadn’t for Plath, and that she had begun writing with passion and precision not only about the problems of patriarchal culture but also about lesbianism as personal desire and political decision. But what exactly, many must have wondered, had happened and how was life dramatized in art?

Rich never wanted anyone to write her biography, or so she some years ago told a colleague of mine who inquired about doing one. Even in “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-vision,” a personal-political essay that has become one of the foundational works of feminist literary criticism, she noted that she had always “hesitated” to use herself as an example in discussing poetry but had reluctantly decided to meditate on her own history. Yet that history is inscribed in both her often surprisingly confessional prose and in the poetry she herself asserted was public, not personal. Indeed, a biography of sorts, both public and private—in other words a life of allegory—can be read throughout her oeuvre. But no, the story isn’t the kind of apparently tell-all narrative in which, say, Robert Lowell specialized. Rich knew Lowell and was particularly distressed by the frankness of some of his disclosures. Perhaps for this reason—or, more likely, because of a long-standing will to privacy—she recorded her own “life studies” in a mode on which she now and then meditated: invisible ink.

In a remarkable analysis of the vital conjunction between past and present, Rich suggested that our versions of our own public and private histories are “Written-across like nineteenth-century letters / or secrets penned in vinegar, invisible / till the page is held over flame” (“Living Memory”). What was once perhaps furtively inscribed is now to be lucidly transcribed, reread as we re-envision the writings of others and revise our own. Strikingly, in “Endpapers,” the last poem in her new Collected Poems: 1950–2012 (W. W. Norton, $50), edited by her son Pablo Conrad, she returns to this point:

The signature to a life requires

the search for a method

rejection of posturing

trust in the witnesses

a vial of invisible ink

a sheet of paper held steady

after the end-stroke

above a deciphering flame.

It’s moving to read these words after contemplating their author’s checks and hesitations. She knew, and explained repeatedly, that hers was “a deciphering flame.” In the passage from her essay “When We Dead Awaken” that is her most influential and widely cited literary assertion, she declared that “Re-vision—the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction—is for us more than a chapter in cultural history: it is an act of survival.” And in the passage from “Planetarium” that I’ve used as an epigraph here, she defined herself as a reader deciphering the “battery of signals” that constitute the text of the world. But even while she was a brilliant analyst of the imperatives encrypted in her culture, she was also, as Ruth Whitman noted, a writer who produced a compelling narrative using “a vial of invisible ink,” leaving us to decipher the life of allegory embodied in her work.

When A Change of World was published in 1951, I was still a schoolgirl, but by the time I had graduated from Cornell as an English major, I’d begun reading Rich’s poems, along with Plath’s. The early ones were easy to understand. Deftly designed, as Auden and others pointed out, they were more or less like what every successful poet was writing at that time. As both her life and her work increased in complexity, moving from such turning points as Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law and Leaflets to the great watershed works included in The Will to Change, Diving Into the Wreck, and The Dream of a Common Language, I thought I followed along, discerning in her revisionary tale my own feminist awakening. Yet now, as I reread her Collected Poems, I realize how much of what she said I didn’t really grasp, even as I’m more than ever astounded by her body of work. This new book is as massive as—or maybe even weightier than—the kinds of “Eng Lit” anthologies Rich must have studied as an undergraduate at Radcliffe: 1,164 pages of thin paper, on which poems spill from page to page! The poet herself, who suffered throughout her career from severe rheumatoid arthritis, might not be able to hand this volume to her most affectionate admirers. And yet she has also written seven collections of prose, a vast archive of letters to her friend Hayden Carruth, and no doubt countless other letters and journals that won’t be available to scholars until the mid-21st century.

Heaving the book across my desk and then abandoning it for the thinner, easier-to-lift individual collections from which it’s composed, I ponder my own experience of Rich’s extraordinary writing. What was it I found, and now still more eagerly find, in her work?

“Someone my age was writing down my life”: so Helen Vendler—later one of Rich’s severest critics—remarked of the early poems. I think I felt the same way, though I was younger than Rich. We had both come of age in the 1950s, the period whose mystifications Betty Friedan so astutely analyzed and which, in one way or another, some of us consciously or unconsciously resisted. Rich, and others following her lead, always argued that at least an impulse toward rebellion was encoded in “Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers,” an elegant meditation on needlework that appeared in A Change of World. Here an elderly terrified female relative, her dead hands “ringed with ordeals she was mastered by,” has nonetheless sewn the images of prancing tigers, “proud and unafraid,” onto a “screen.” Like Blake’s “Tyger, Tyger, burning bright / In the forests of the night,” these sleek beasts, undaunted by the “massive weight of Uncle’s wedding band,” will endure. Though screened by elaborations of marriage, they prefigure the poet’s own feminist images of redemption.

And yet, in “An Unsaid Word,” as Vendler noted, the young Rich also deferentially celebrated the wifely woman who

… has power to call her man

From that estranged intensity

Where his mind forages alone,

Yet keeps her peace and leaves him free,

And when his thoughts to her return

Stands where he left her, still his own,

Knows this the hardest thing to learn.

Yeatsian in its eloquence, this youthful nugget of ’50s wisdom tersely acquiesces in just the premises of the feminine mystique that Rich would question in Of Woman Born even while obliquely defying them: such patience with a man’s “estranged intensity” is, after all, “the hardest thing to learn.”

By the time Rich composed such widely anthologized works as her first feminist manifesto, “Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law” (1958–60); the elegy for her marriage (and for heterosexual culture), “Diving Into the Wreck” (1972); and her powerful lesbian sequence, “Twenty-One Love Poems” (1974–76), she had journeyed into a personal and public world that was changed, changed utterly, as Yeats would have put it too. Perhaps the terrible beauty of sex change—not biological change but spiritual and psychological metamorphosis—had been born in her, and in her culture, as a reaction against the fatiguing stereotypes of the ’50s. In “From a Survivor,” one of the few explicit elegies she wrote for her dead husband, she mourned his suicide:

Next year it would have been 20 years

and you are wastefully dead

who might have made the leap

we talked, too late, of making.

Yet at the same time, in the central passage I’ve repeatedly quoted, she commemorated the changes of world her own will had brought about, not “a leap / but a succession of brief, amazing movements.” Grieving for the wreck of a society in which both “she” and “he” had been drowned, she exulted in her own rebirth as a new creature, androgynous and unprecedented.

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the one who find our way

back to this scene

carrying a knife, a camera

a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

(“Diving Into the Wreck”)

From this moment of rueful regeneration in the 1970s, Rich would go on to write the grave and powerful quasi-sonnet sequence “Twenty-One Love Poems,” in which her erotic adoration of her lover inspired a newly mythical self-definition: “greeting the moon … a woman, I choose to walk here. And to draw this circle.” And then, in yet another movement toward re-vision, she would explore her own half-Jewish origins in the introspective “Sources” and her American identity in the extraordinary Whitmanesque cadences of “An Atlas of the Difficult World.” Finally, in “Atlas,” after reimagining and rediscovering herself, she acknowledged that “I am bent on fathoming what it means to love my country,” as she asked us all to turn “again to the task you cannot refuse.” As I take up the task of reading and rereading these often prophetic poems, much becomes clear to me simply from the visible letters on the page—and yet I sense, too, that I cannot refuse an interpretation of what is inscribed beneath and within those letters in the invisible ink of Rich’s poetic genius. To fully comprehend this impressive collection, then, we must also do as she asked in the final poem of the volume: hold the book “steady / after the end-stroke / above a deciphering flame.”